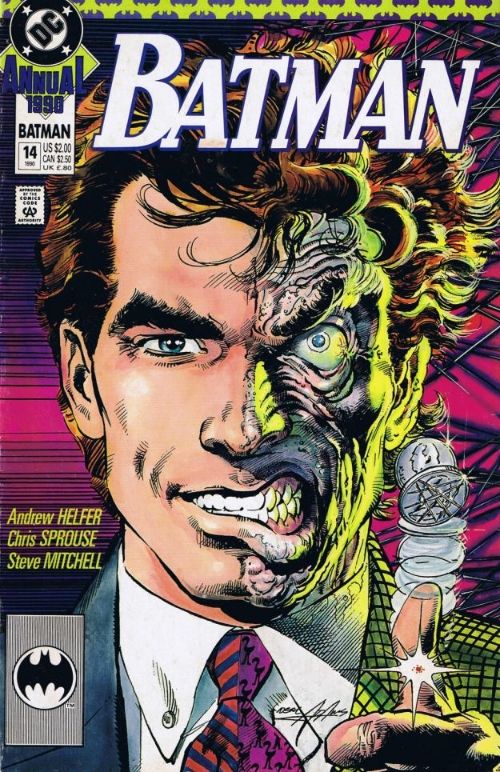

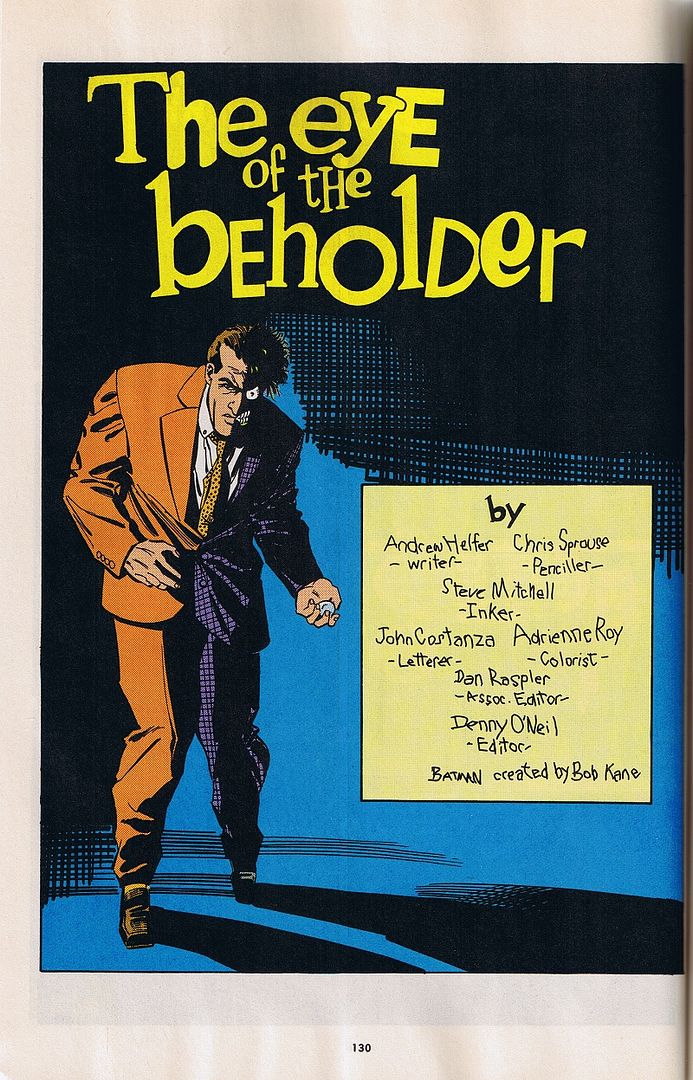

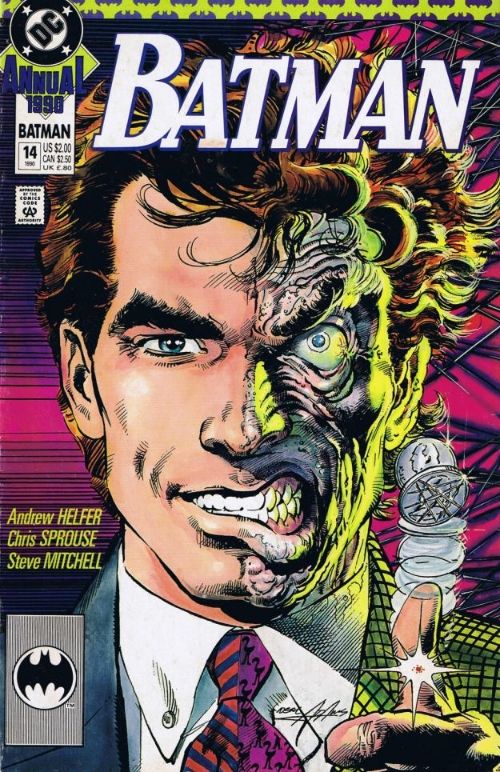

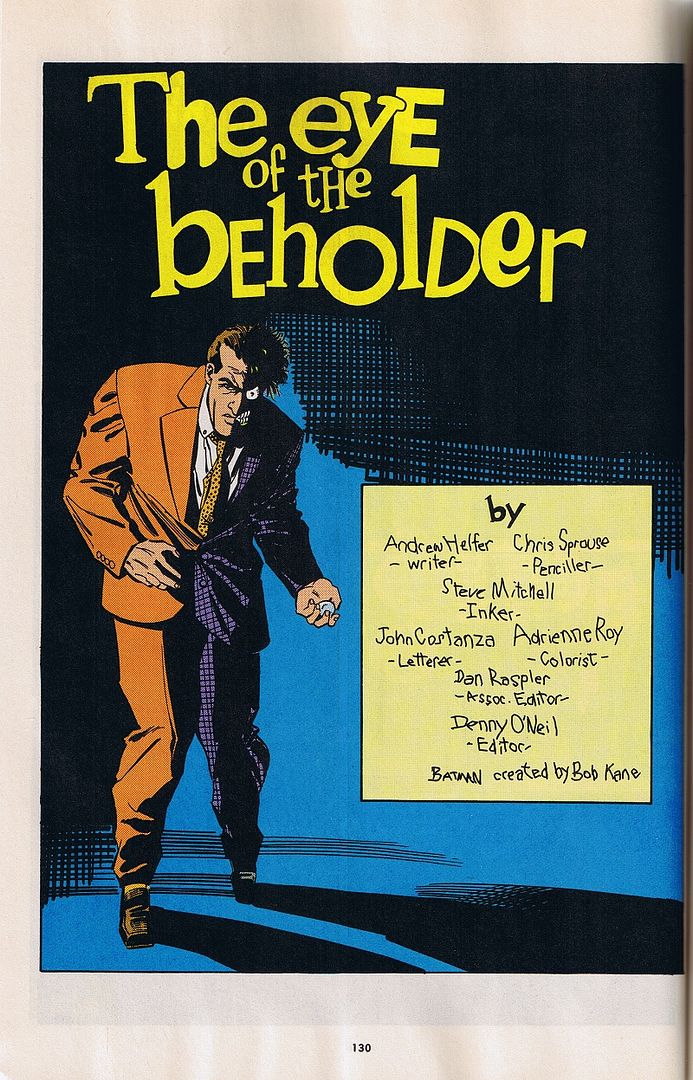

The Definitive Harvey Dent Story: “Eye of the Beholder”

It's difficult to encapsulate just how important Eye of the Beholder is both to the character of Harvey Dent and for me, personally, as a fan. To simply call it the greatest Two-Face story of all time (as some have done) doesn't do it justice.

First off, it's an incredibly influential story, although that's mainly because so much of it was directly incorporated into Jeph Loeb's Batman: The Long Halloween, which in turn directly influenced Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight. Despite this, the story remains out of print, and thus unknown to all but the more dedicated fans who make the effort of finding old copies on eBay. As such, I am posting the bulk of the issue here, at least until this issue becomes available in an accessible digital form. Because this is a damn good story, one that deserves to be read one way or another.

More than just a villain origin, EotB is a powerful and tragic psychological thriller, the first story to explore the idea-suggested by the wonderful Grace Dent story in Secret Origins Special that came out mere months earlier-that the seeds of Harvey's insanity were planted long before the acid bath. Other stories have since explored the root of his simmering rage and (depending on the writer) split personality, but not ONE of those stories, not even the truly great ones like J.M. DeMatteis' Two-Face: Crime and Punishment, have recaptured the twisted nuances of how EotB reimagined Harvey Dent.

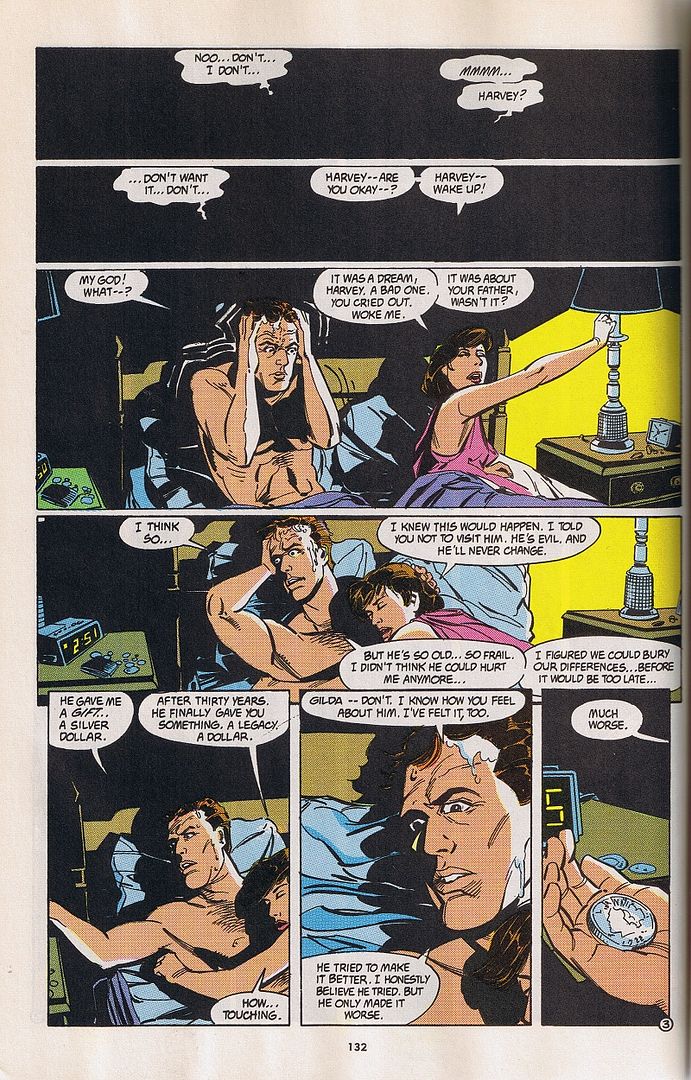

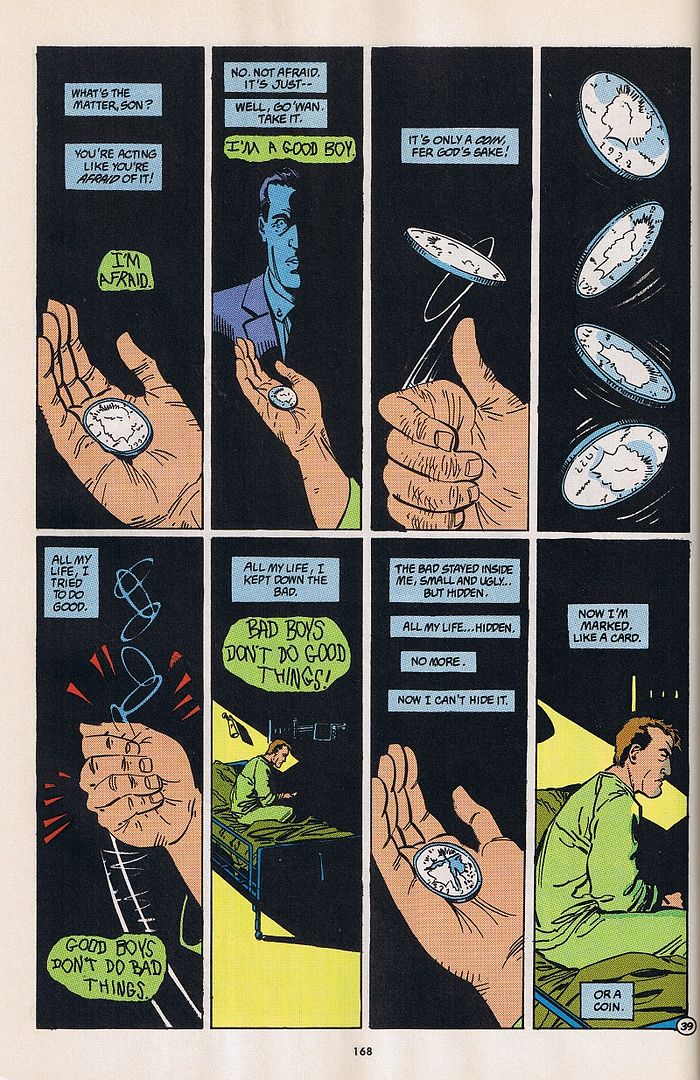

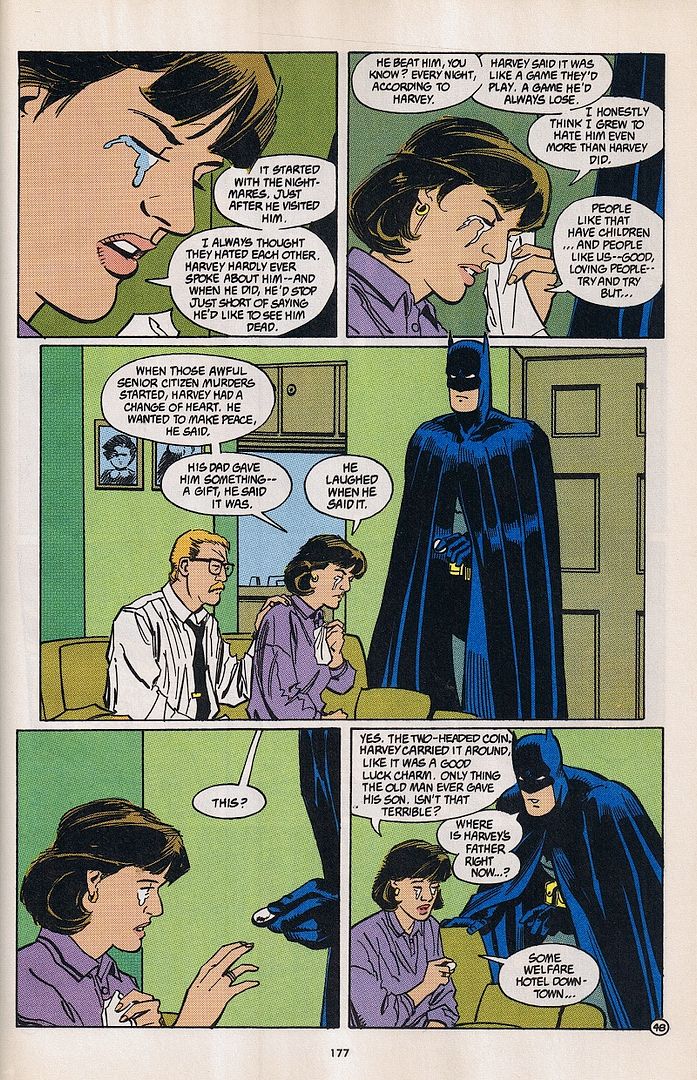

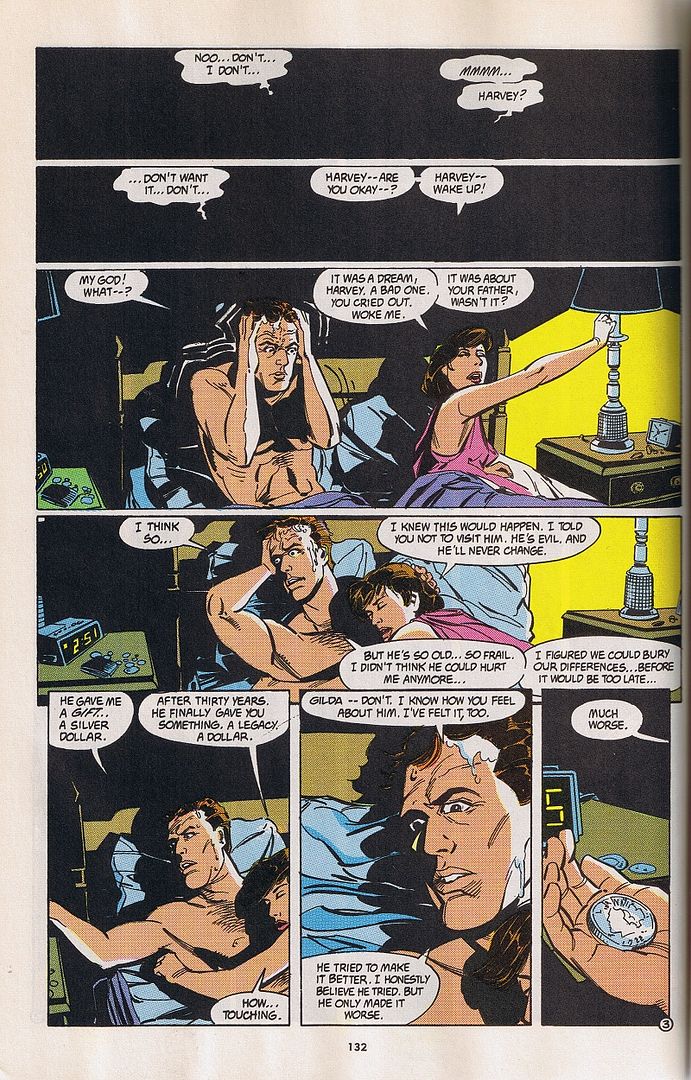

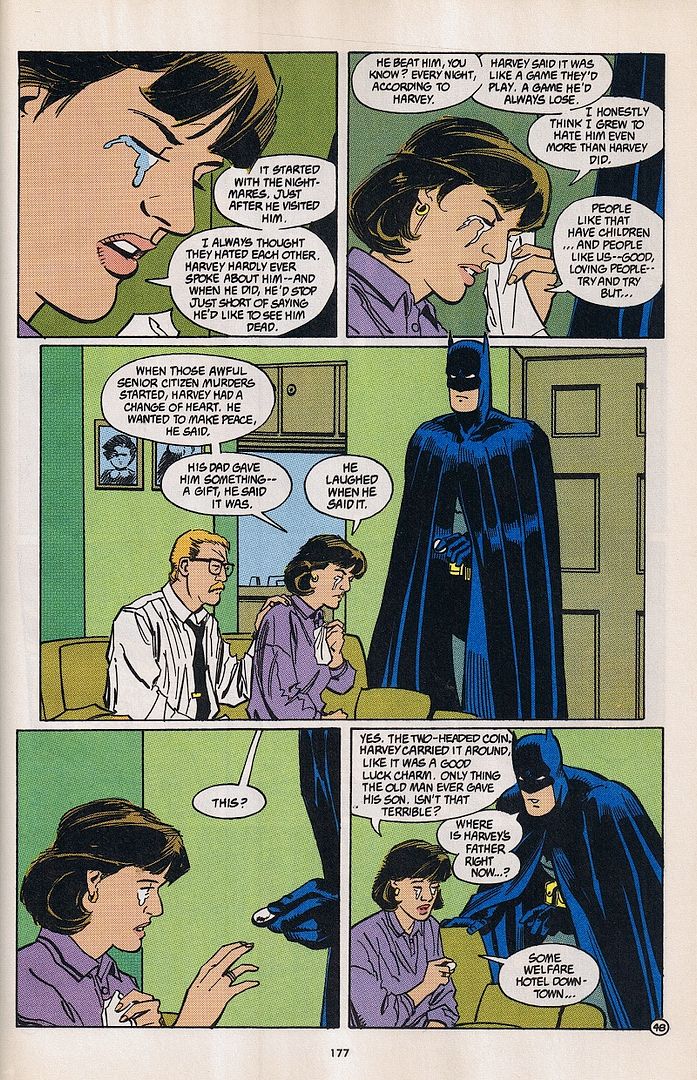

Right from the start, author Andrew Helfer introduces an original concept to Harvey's origin: the existence of his father, who-in case you couldn't tell-wasn't exactly father of the year material. We don't yet know exactly what he did, but Gilda doesn't mince words: “he's evil.” At this point, you may be assuming that he was abusive, which subsequent stories have included to varying degrees. But that's only half the story (sorry, I'll try to keep the puns to a minimum).

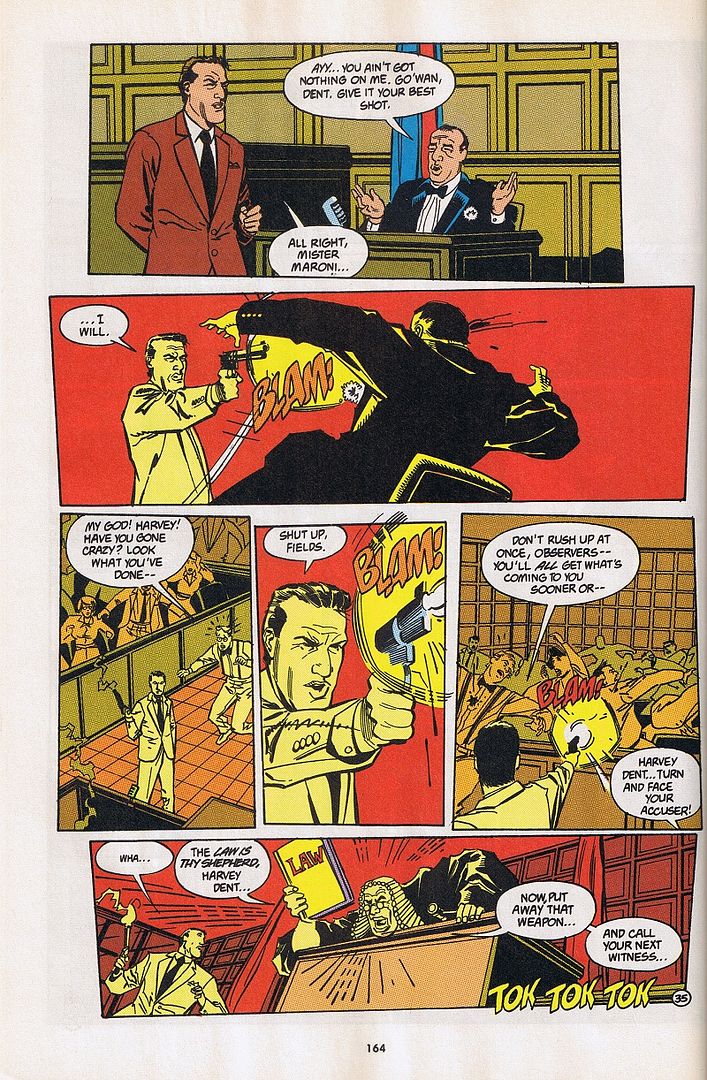

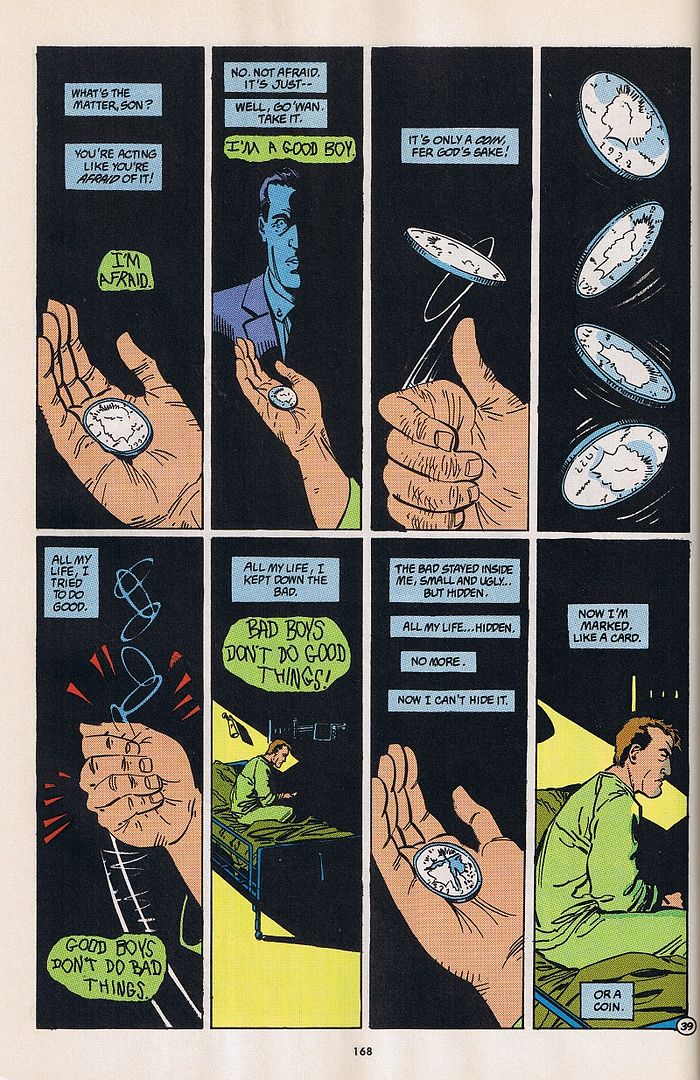

Helfer's other big original concept is that the fateful coin was given to Harvey by his father, rather than it being Boss Maroni's lucky token and the key piece of evidence in the infamous trial where Harvey got scarred. To fans of Two-Face's classic origin, this is a huge and potentially sacrilegious change, but it's not one which Helfer has made arbitrarily. And of course, it's the first of several details which ended up incorporated into The Long Halloween and The Dark Knight.

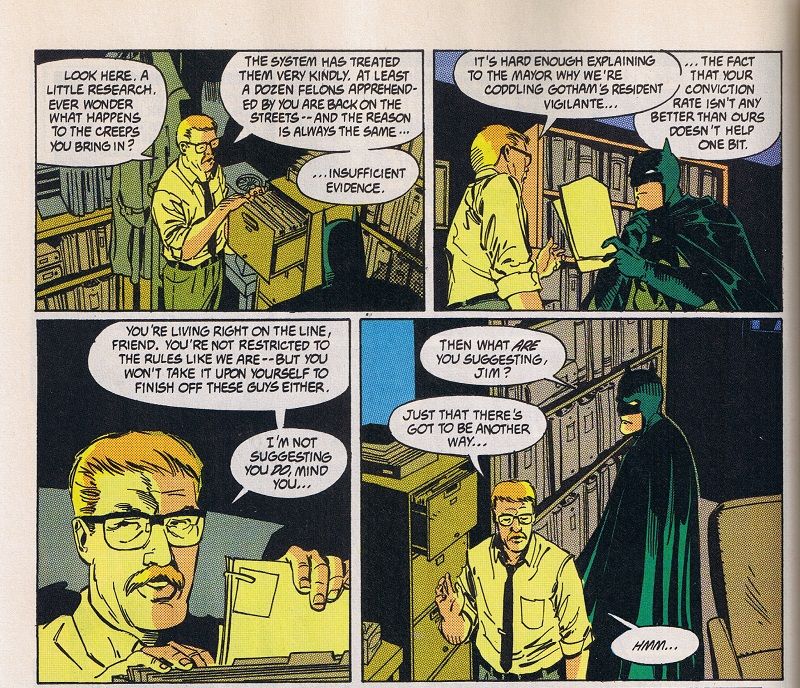

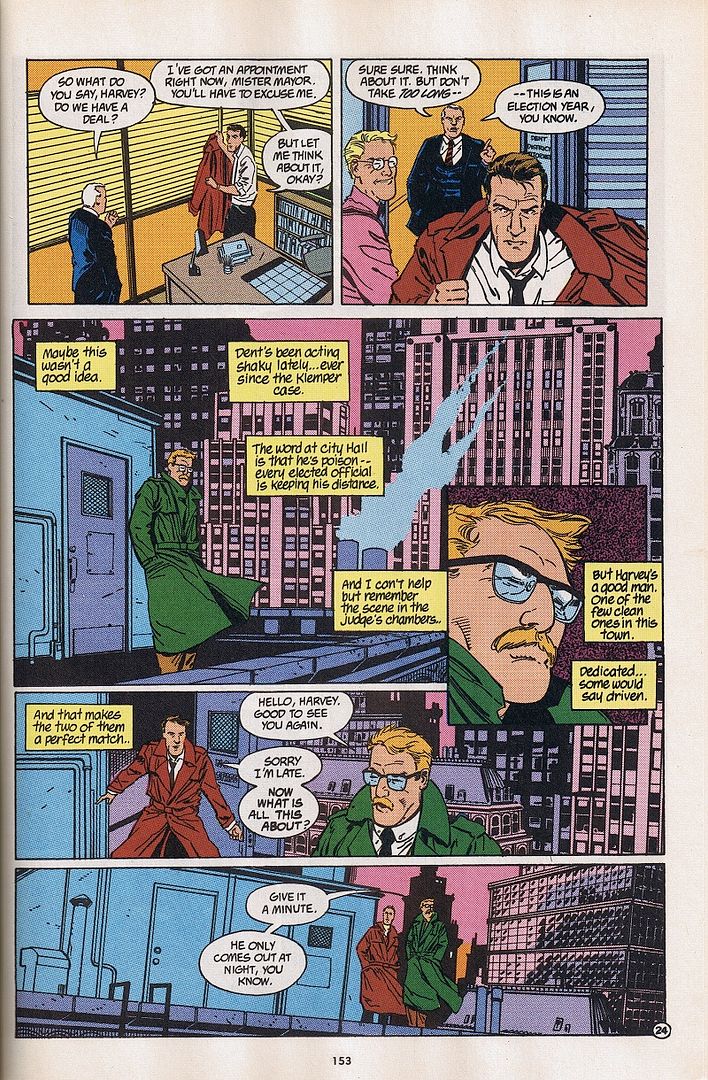

For now, though, the focus shifts to the plot, which takes place at some point after the events of Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli's Batman: Year One, as evinced by Gordon's rank as Captain and the fact that his still has reddish hair. I was originally going to include this part of the story, but frankly, it takes up entirely too much of the issue and barely features Harvey until near the end. Since this post is review to be long enough anyway, I hope you'll forgive me for skipping through just the most pertinent bits.

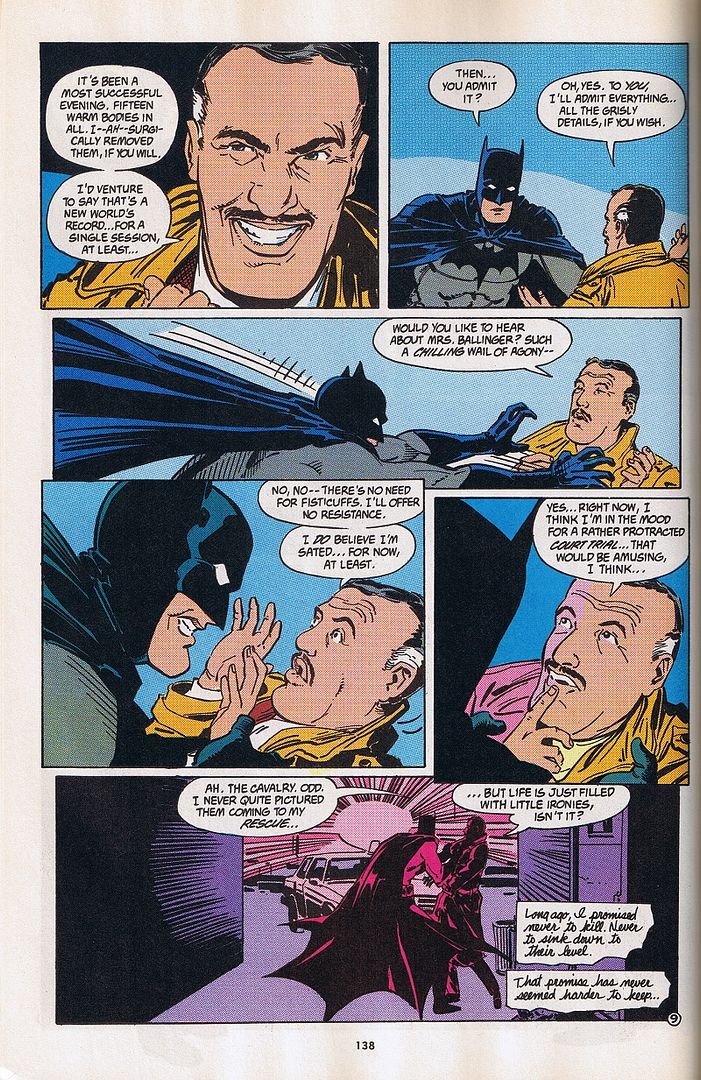

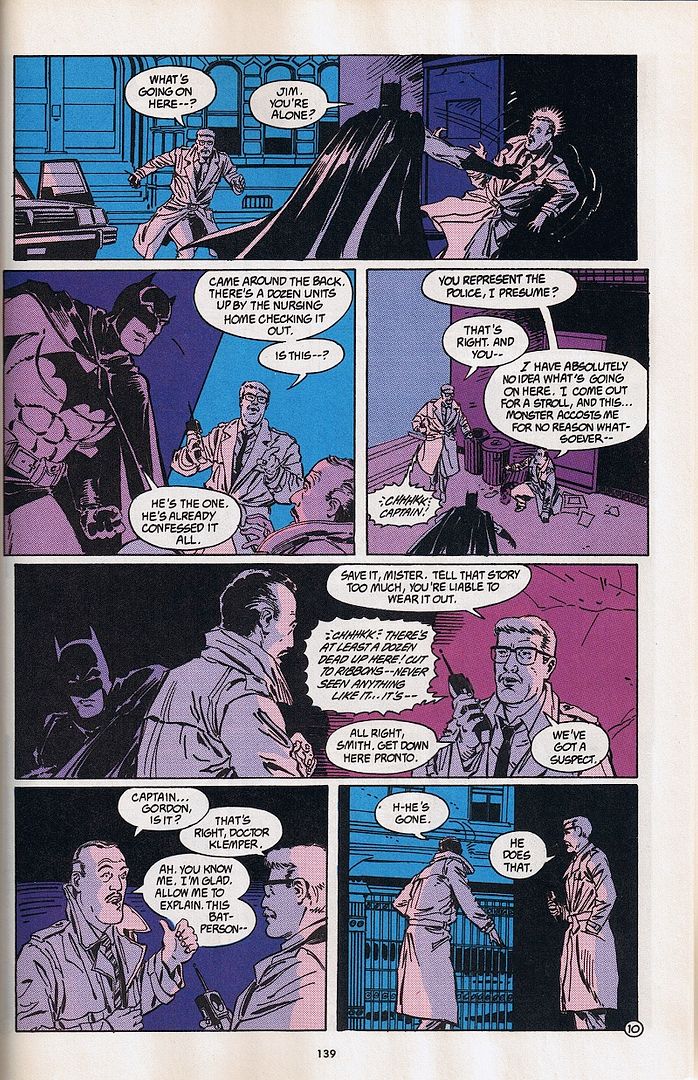

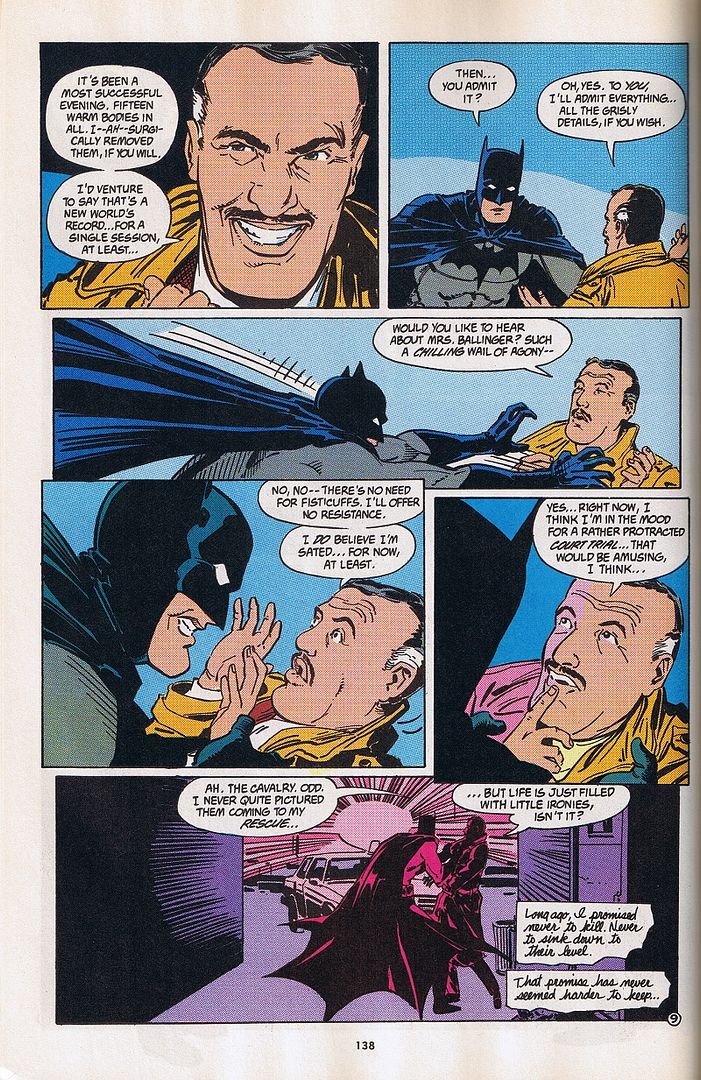

Over the previous three weeks, sixteen elderly people have been brutally murdered by a killer dubbed by the press as the “Senior Slasher.” After receiving a report of a disturbance at a nursing home, Batman finally confronts the killer, who happens to be a dignified gentleman by the name of Dr. Rudolph Klemper (“Internist to the stars. Call me Rudy”) who happily confesses to murdering a fresh crop of aged innocents.

“He does that.” Another moment that was used in both TLH and TDK, originated here.

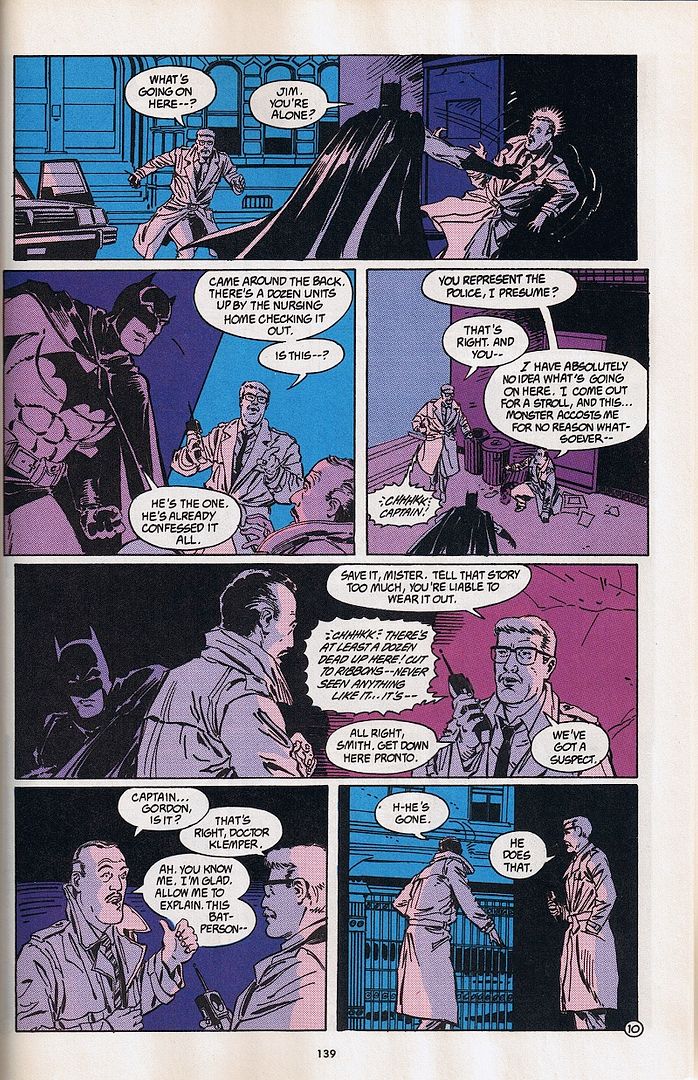

As you can see by the last couple panels there, Klemper's personality changes completely, and he professes both innocence and outrage at his arrest, threatening to sue the city. His performance doesn't fool Gordon, but unfortunately, knowing that Klemper is the killer isn't the same as having hard evidence linking him to the fifteen latest murders.

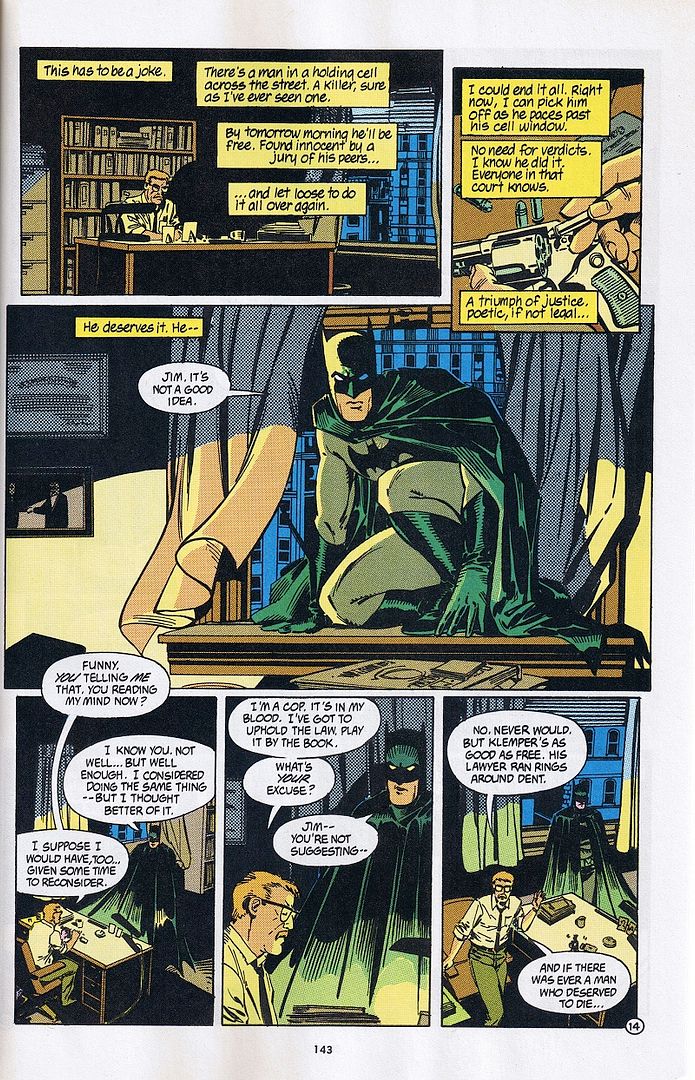

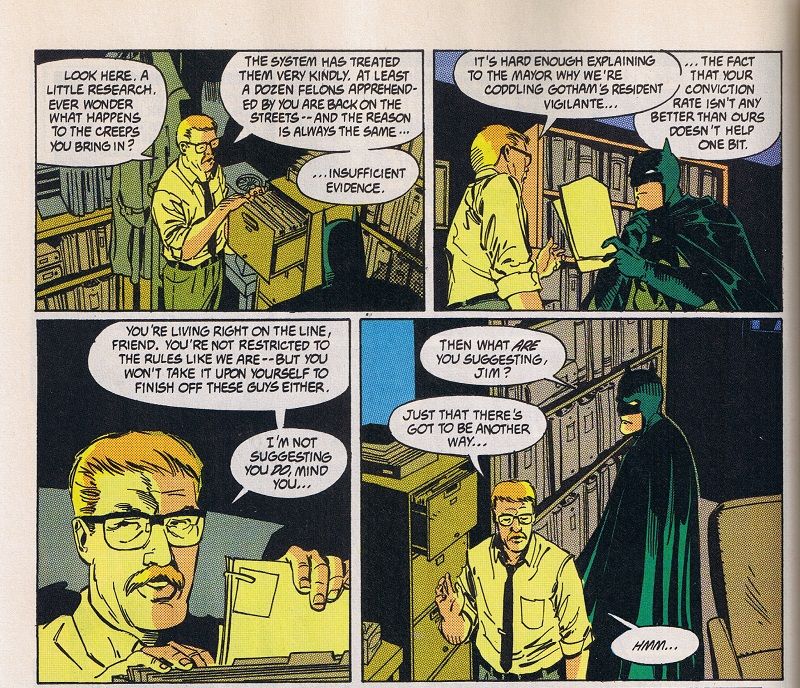

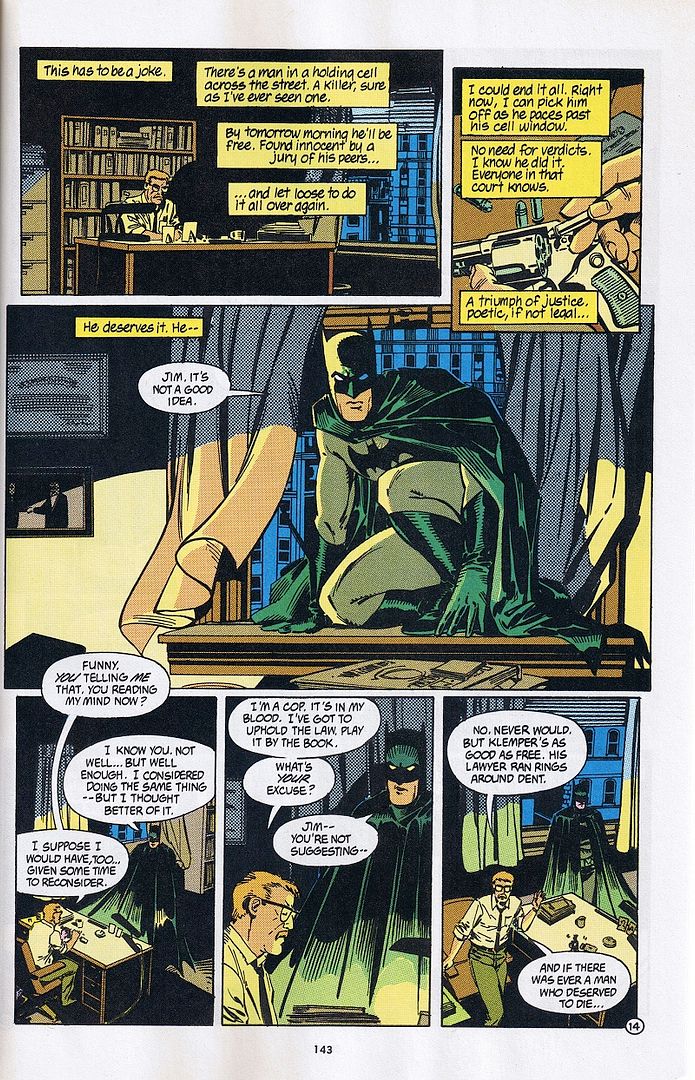

As thus, the unenviable task falls to D.A. Harvey Dent, who futile struggles for six months of the “protracted court trial” to make the charges stick. Despite his best efforts, however, the evidence is only circumstantial, and to make matters worse, Klemper's performance remains unwavering. After the closing statements are made and everyone awaits a verdict, even Jim Gordon considers taking the law into his own hands.

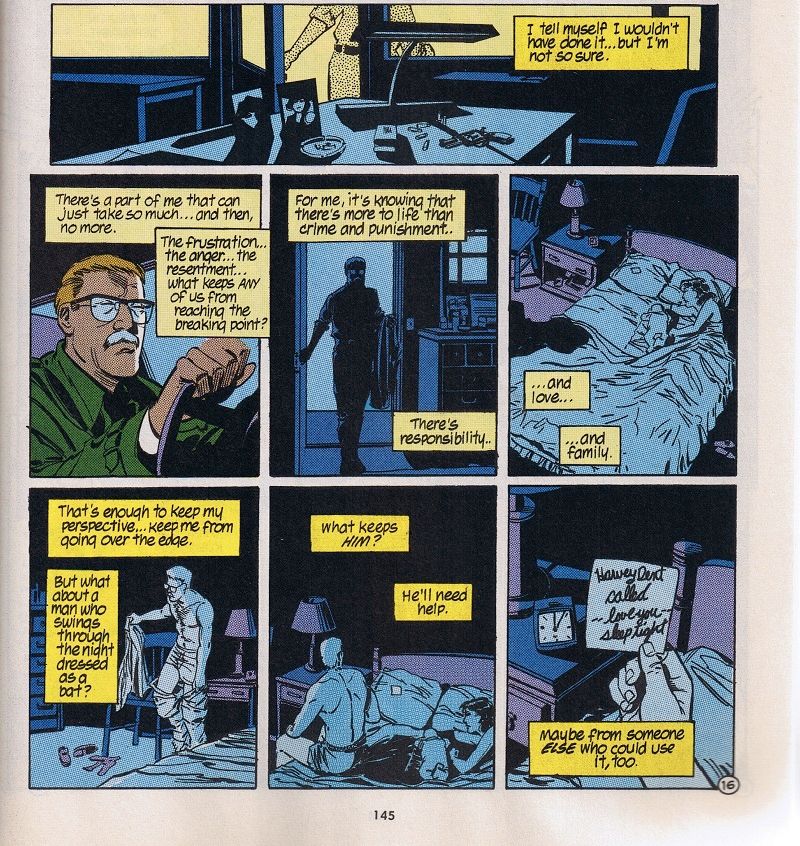

It's a little startling to see both Batman and Gordon both feeling tempted to commit murder, especially given some of the monsters they'll both be facing (and sparing) throughout their careers. By introducing a killer who is so loathsome, so horrifying, that it drives both men to consider doing the unthinkable, we get to see how even Batman and Gordon are under pressure from the same forces which will eventually help to break Harvey Dent.

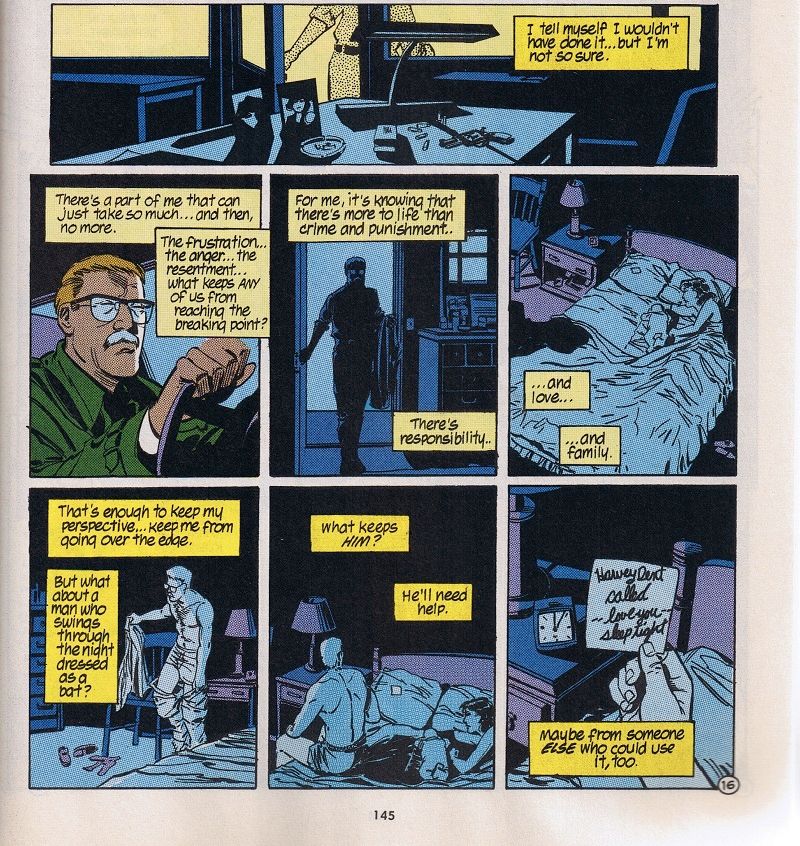

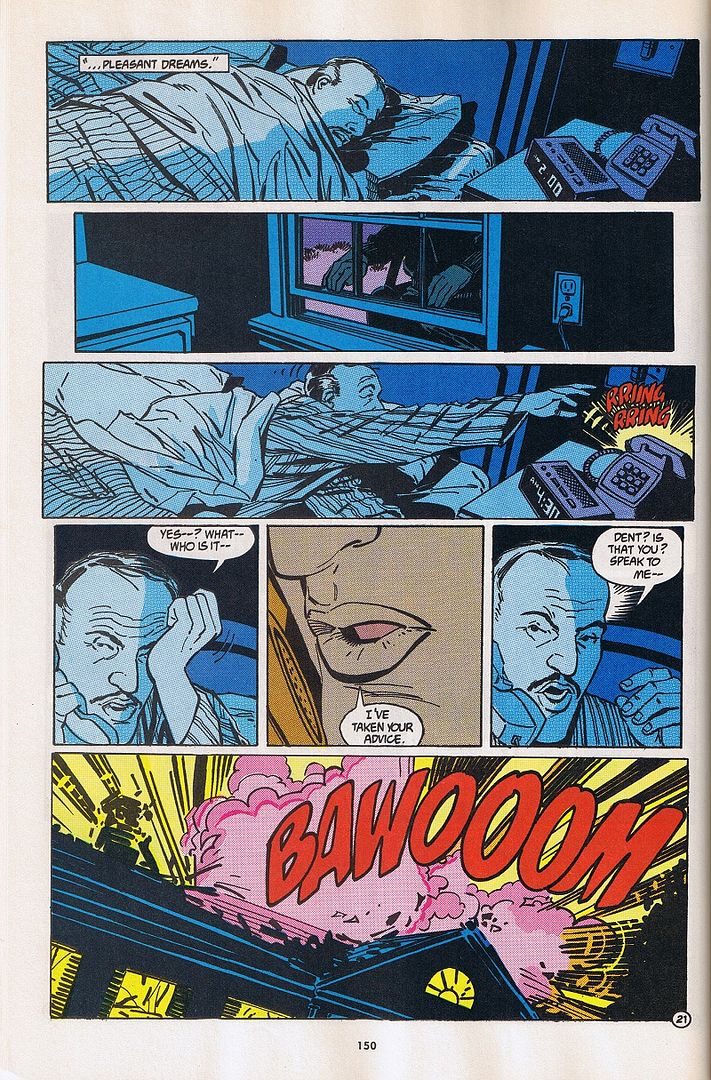

I don't know if it was intentional, but I like how the last few panels of Gordon and his family mirrors Harvey and Gilda in their own bed earlier on. To me, this just hammers home the suggestion that Gordon, just like Batman, intimately understands the stress which-unbeknownst to either man-is already weighing on Harvey. While we know that Harvey will himself eventually cross the unforgivable line, the Klemper situation suggests that Batman and Gordon might have done the same themselves under other circumstances.

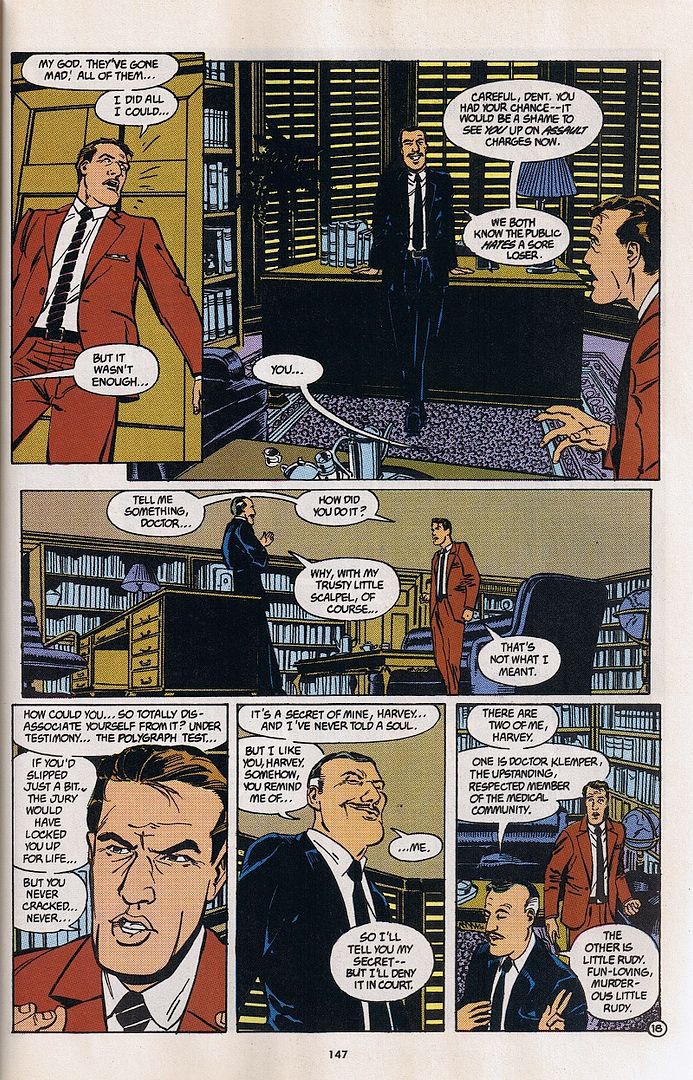

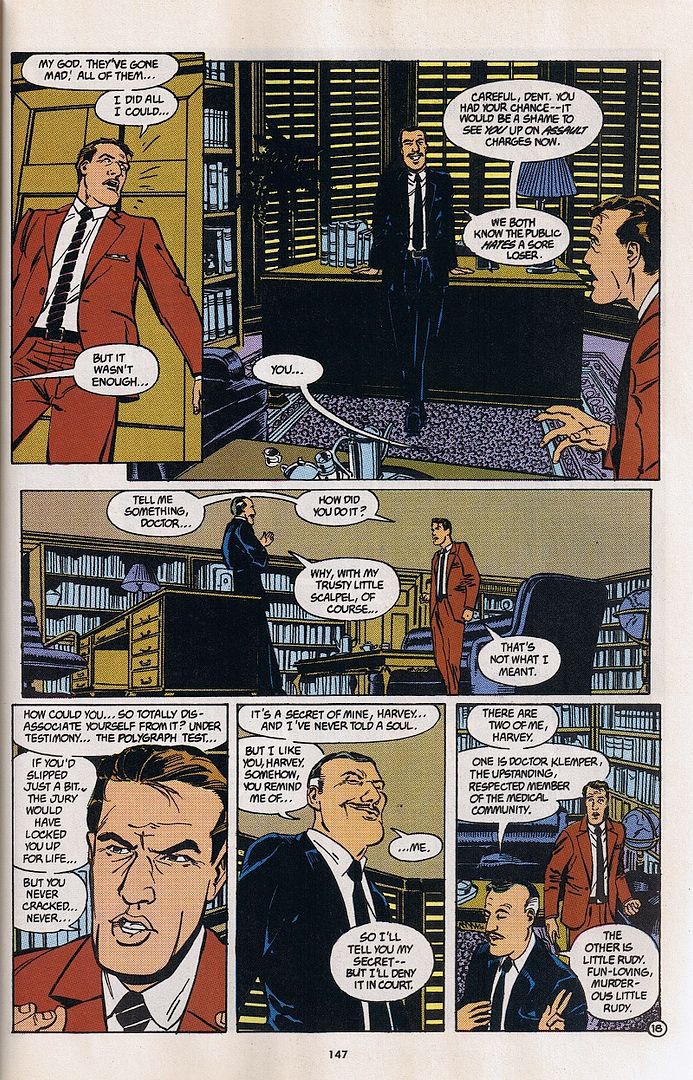

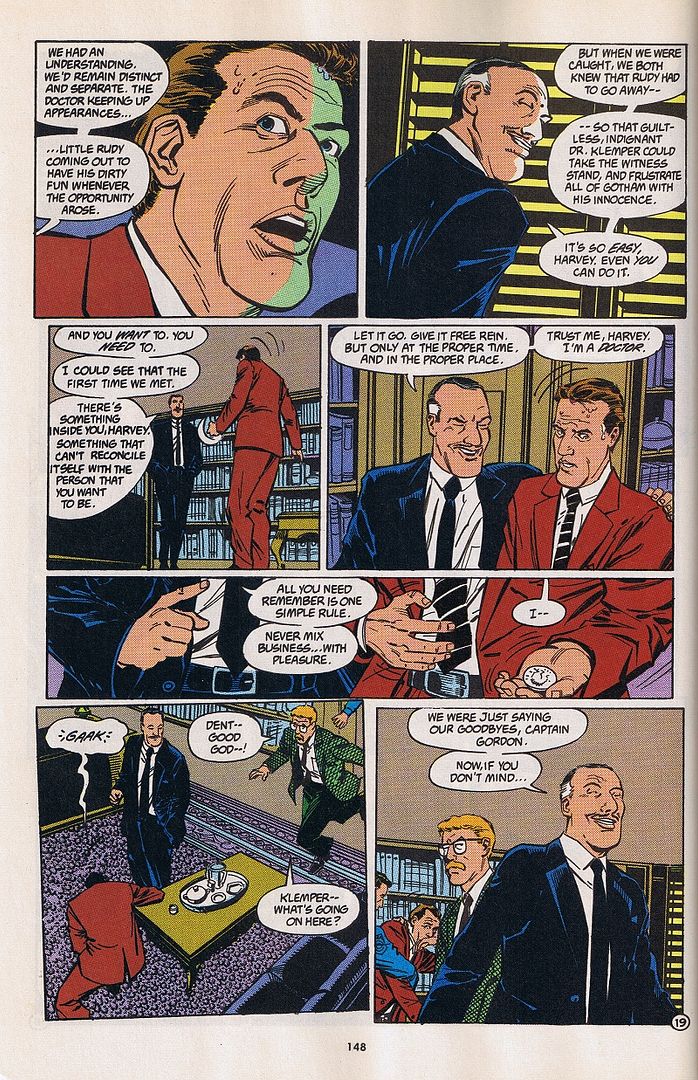

Heck, the same might be said for much of Gotham City itself, as we see the next day, when the Klemper verdict comes in as not guilty. The courtroom explodes with an angry mob of spectators and family members of victims, furious at both the killer and the D.A. who failed to put him away. In the confusion, Klemper vanishes, and Harvey seeks refuge in the judge's chambers, only to find the monster waiting there for him.

It's interesting that Klemper feels to free to confess in Harvey's presence, given that he felt the same way with Batman. I have to wonder if he saw a bit of himself in Bruce's dual nature as well? Seems like a missed opportunity to draw parallels between Bruce and Harvey to me, but oh well.

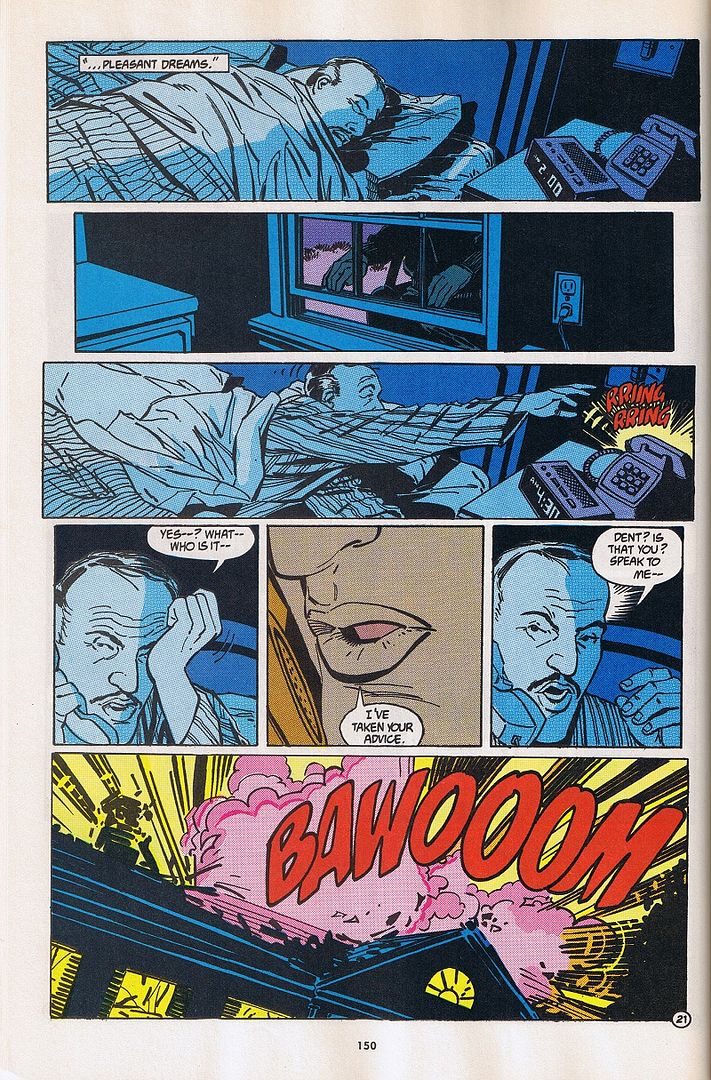

Klemper heads back to his lavish mansion, surrounded by the company of friends who call Dent “a buffoon” and offer to help Klemper get back on his feet now that his good name has been sullied. Klemper modestly denies any assistance, assuring them that “I've filed a civil suit for false arrest against the District Attorney's office. Once that's settled, money won't be a problem.” The next phase of his plan is clearly to ruin Harvey and “encourage him to pursue other avenues of employment. I doubt he'll be reelected after we reach a settlement.” It's hard to tell whether Klemper's ultimate goal is to torment or “liberate” Harvey, but we never find out either way.

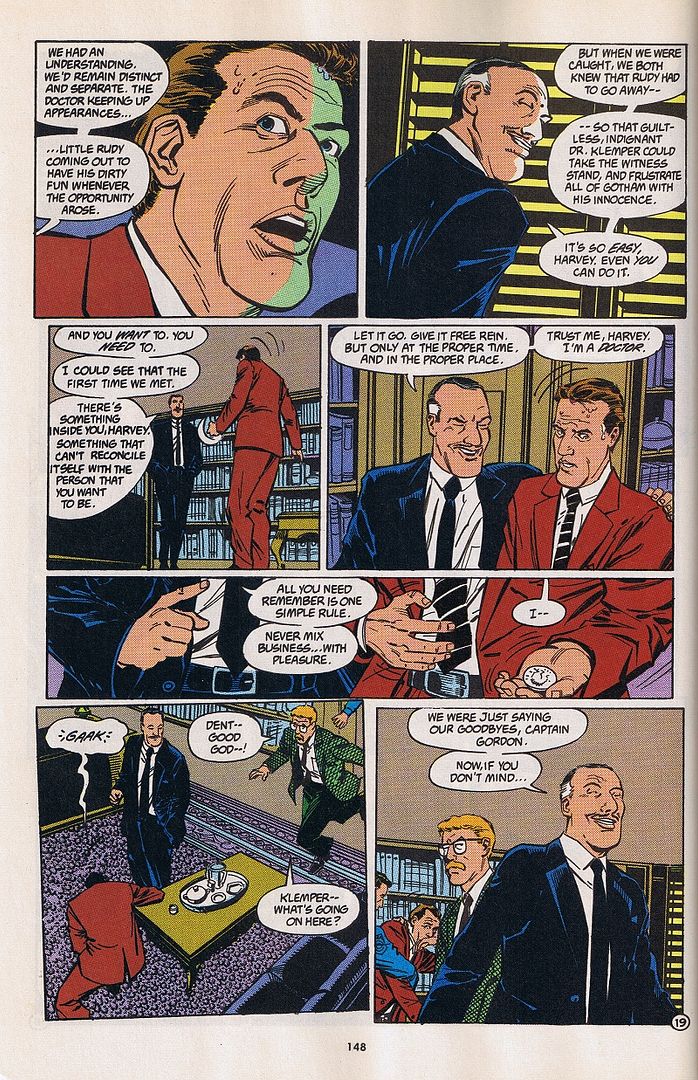

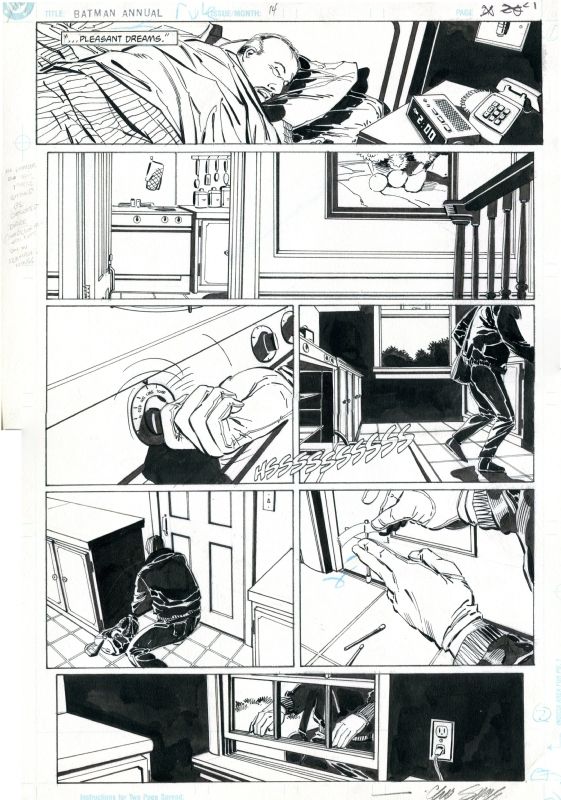

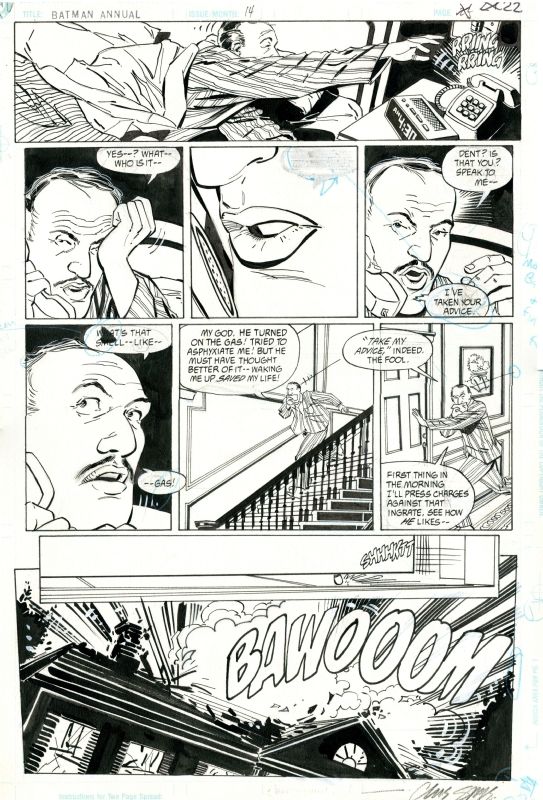

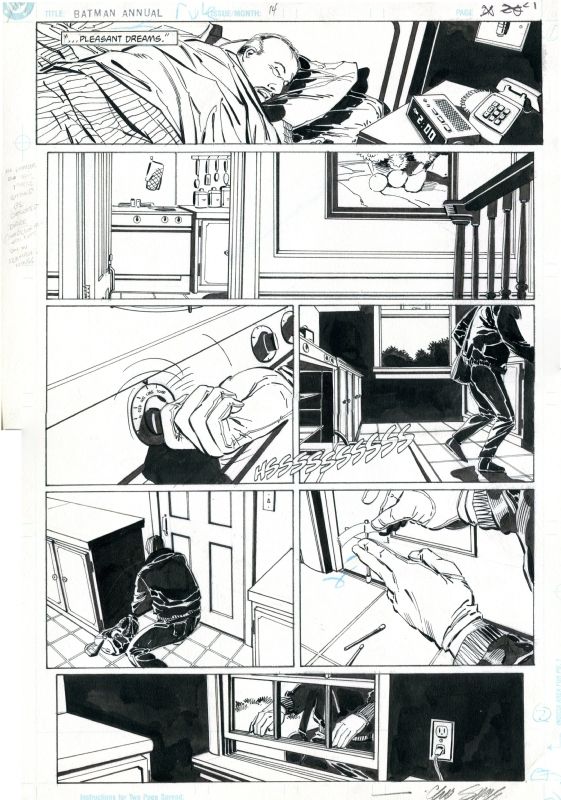

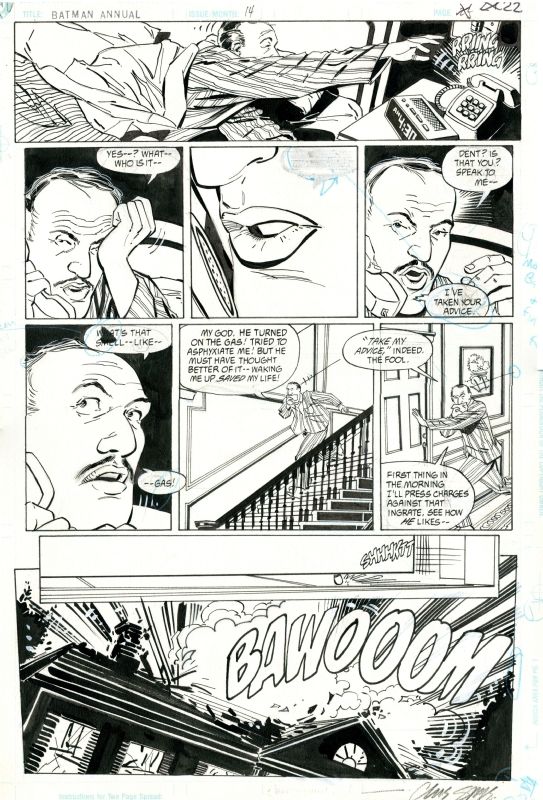

First off, it's worth noting that this page was originally a longer two-page scene which actually showed just how Harvey orchestrated Klemper's demise. I spoke to artist Chris Sprouse at a convention a couple years ago, and he told me that they changed the scene because the higher-ups at DC didn't think that it was a good idea to show kids a step-by-step instructional guide for how to blow someone up. Here's the original two-page version of the scene:

I have to say, I prefer the elegant simplicity and ambiguty of the edited page. We don't really need to see Harvey's Colombo-villain-esque methods, and Klemper's dialogue feels a bit too melodramatic for this story. If he hadn't exploded, I could almost imagine him twirling his silly little mustache while gloating over “the fool” Dent.

Either way, I must admit, this moment is my single biggest complaint about EotB. Much as I love the story as a whole, I'm personally against the idea that Harvey killed anyone in cold-blooded murder before he became Two-Face, especially this early in the story. The only way this is acceptable is if we understand that this is the first manifestation of his other personality, but considering that the personality conveniently vanishes until much, much later on, it doesn't really hold water. This moment should have been saved for after he became Two-Face, keeping it around as another factor that's slowly eating away at Harvey from the inside.

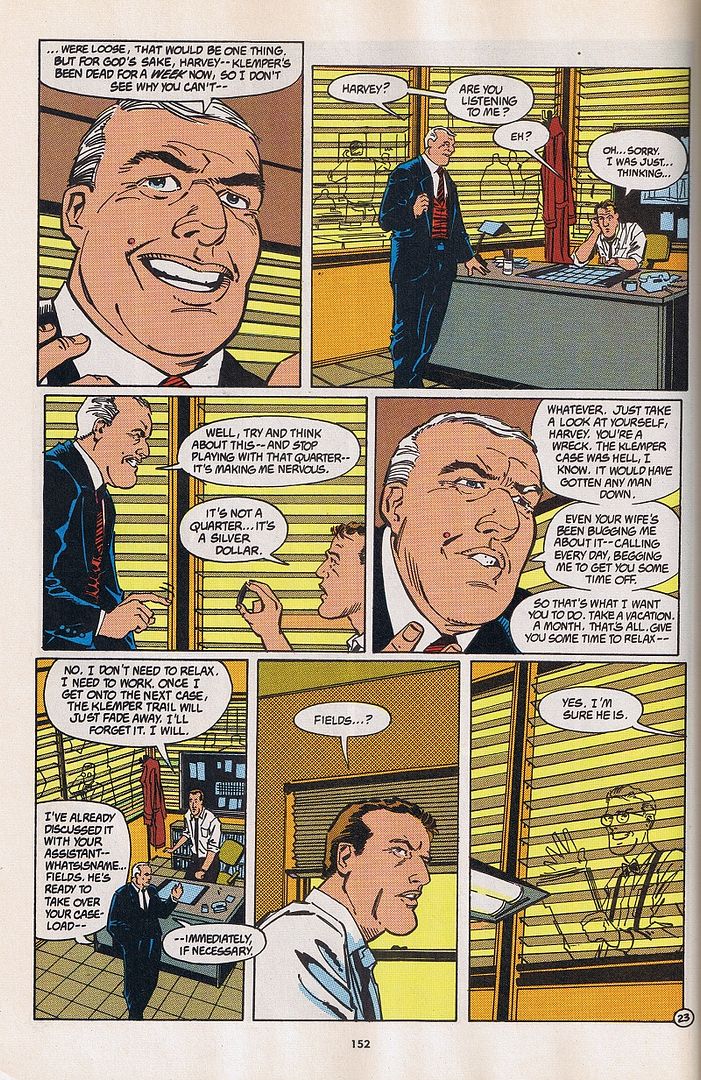

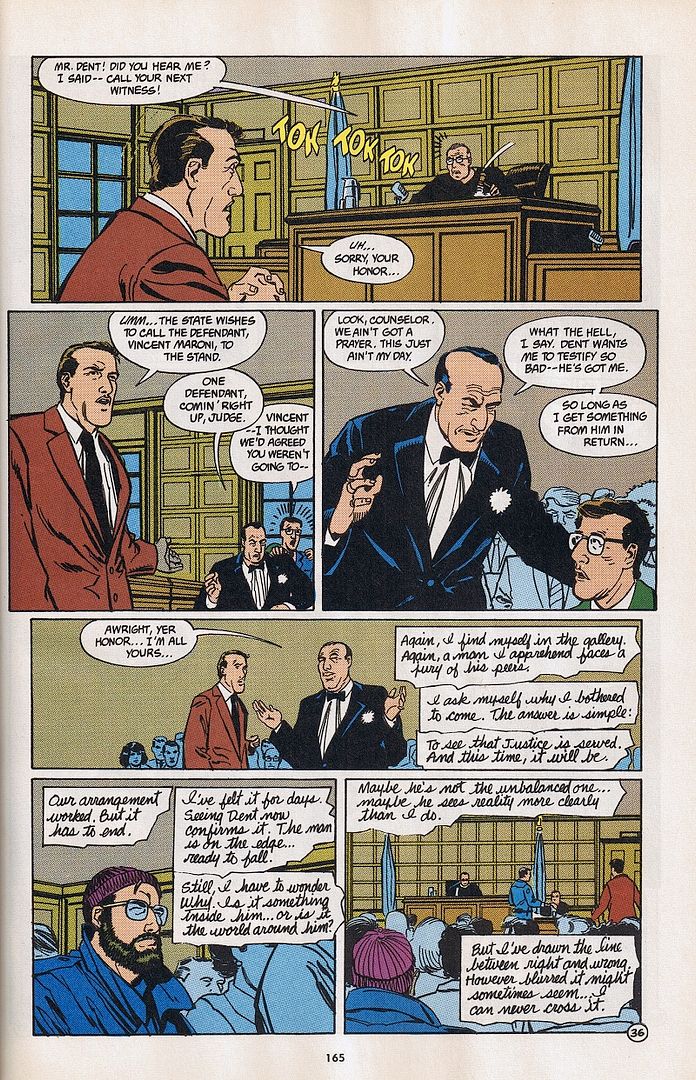

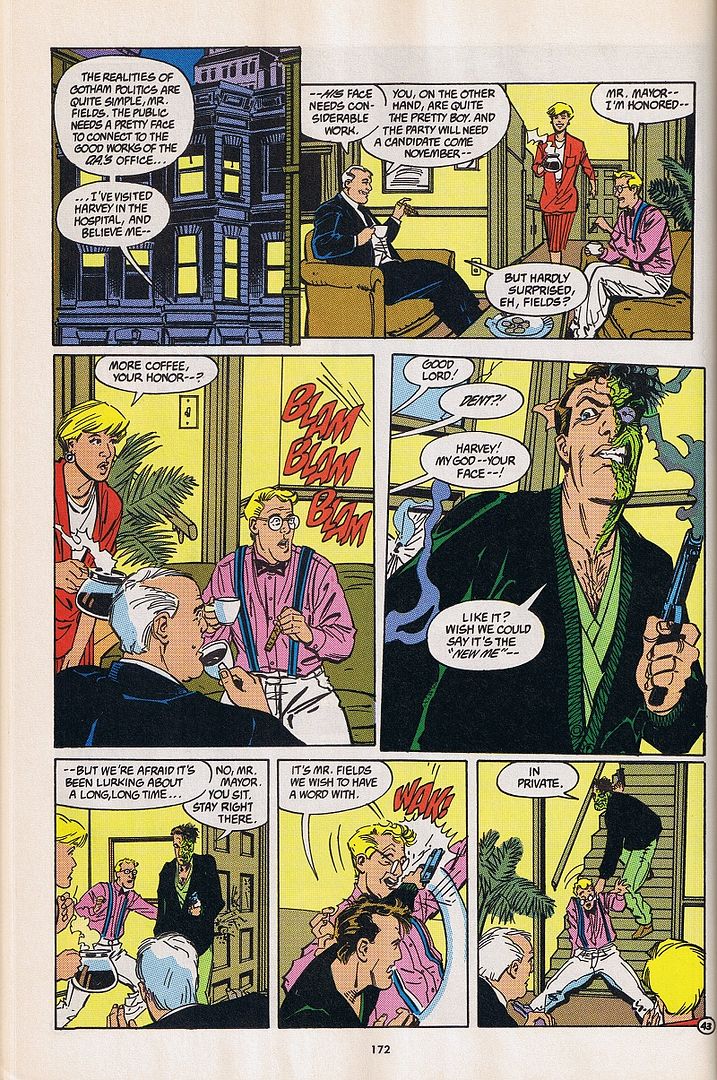

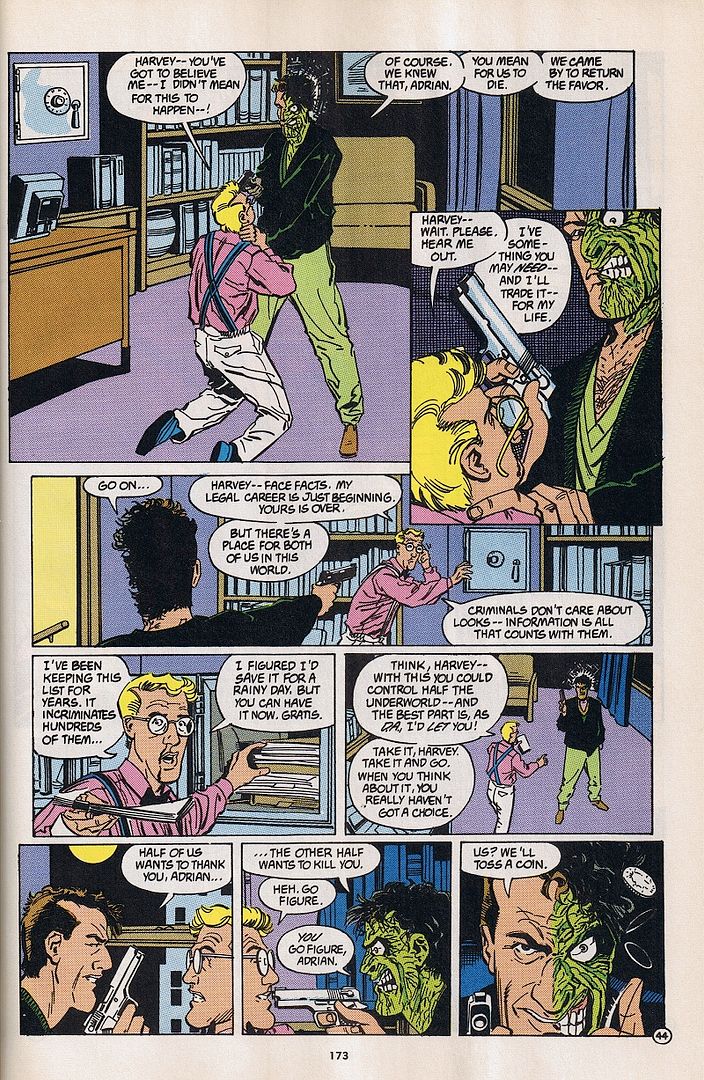

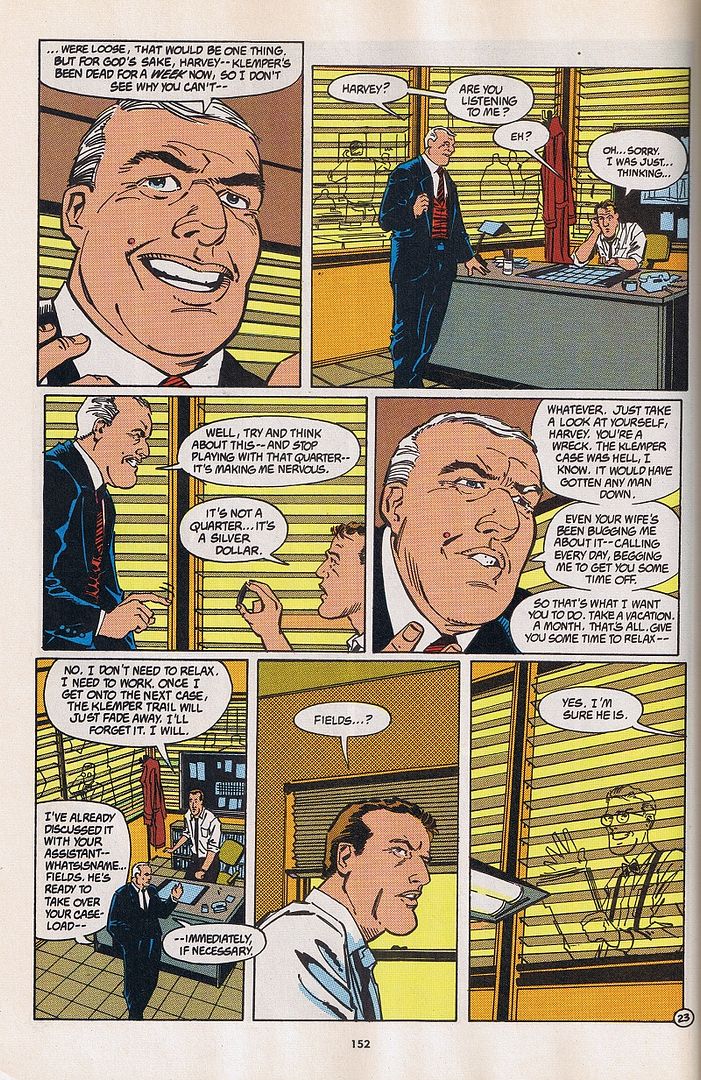

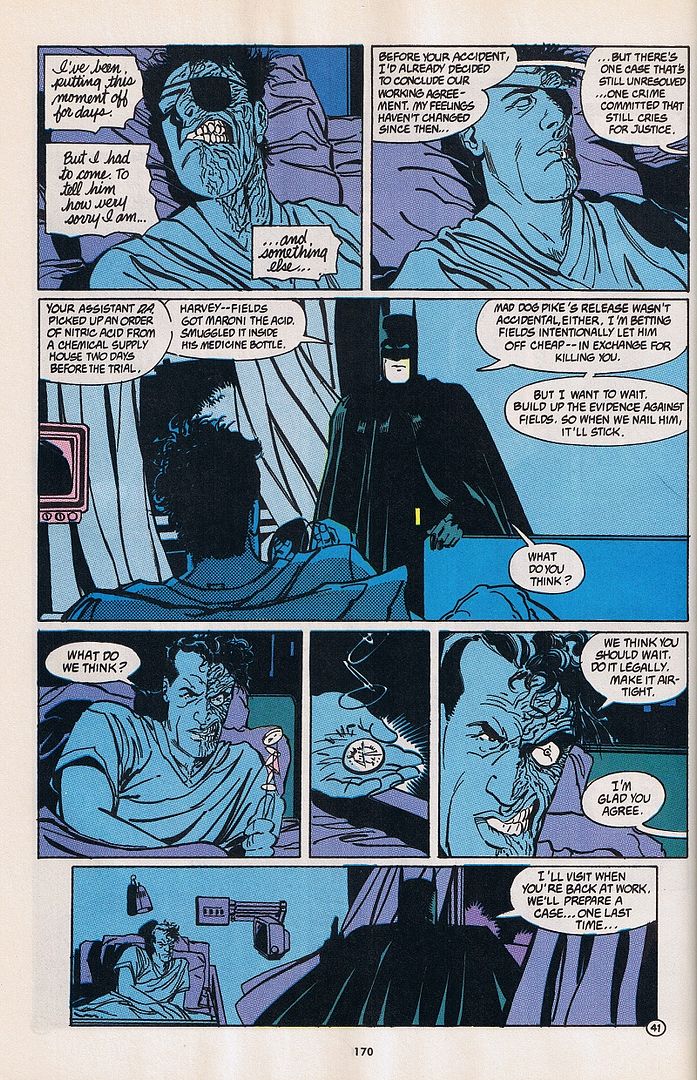

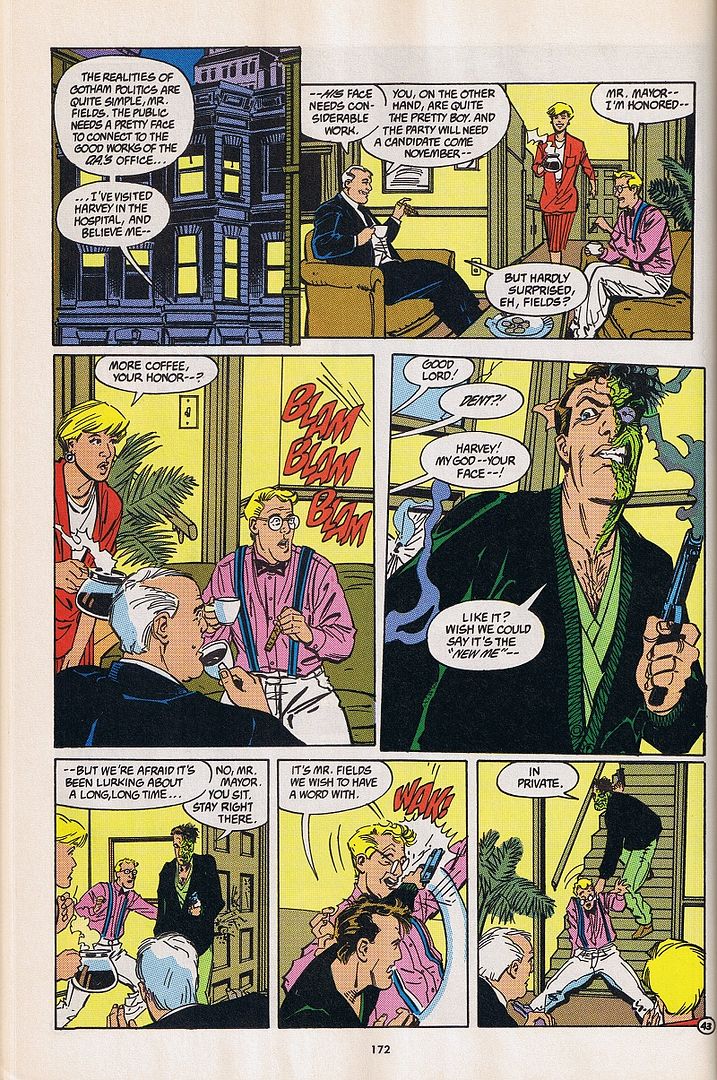

Fans of The Long Halloween will recognize that four-eyed little weasel as Adrian Fields, who was arbitrarily renamed “Vernon Fields” in TLH, where he was depicted as being more mousy and unassuming. Here, he's instantly depicted as being so smarmy that even Harvey is already mistrustful of him.

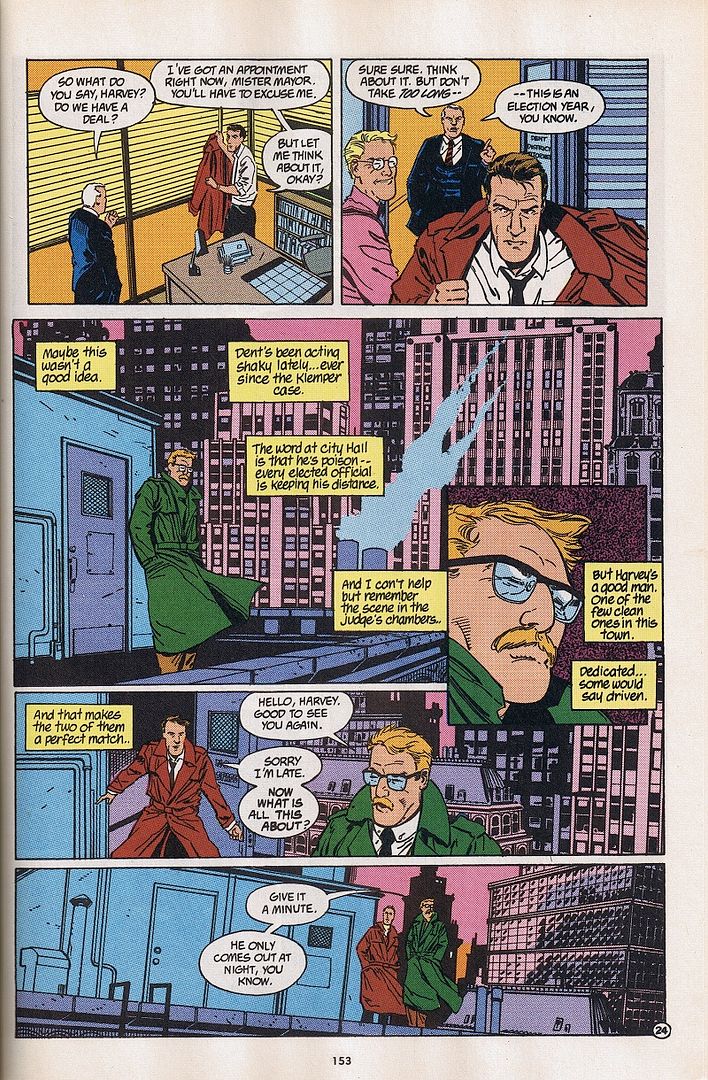

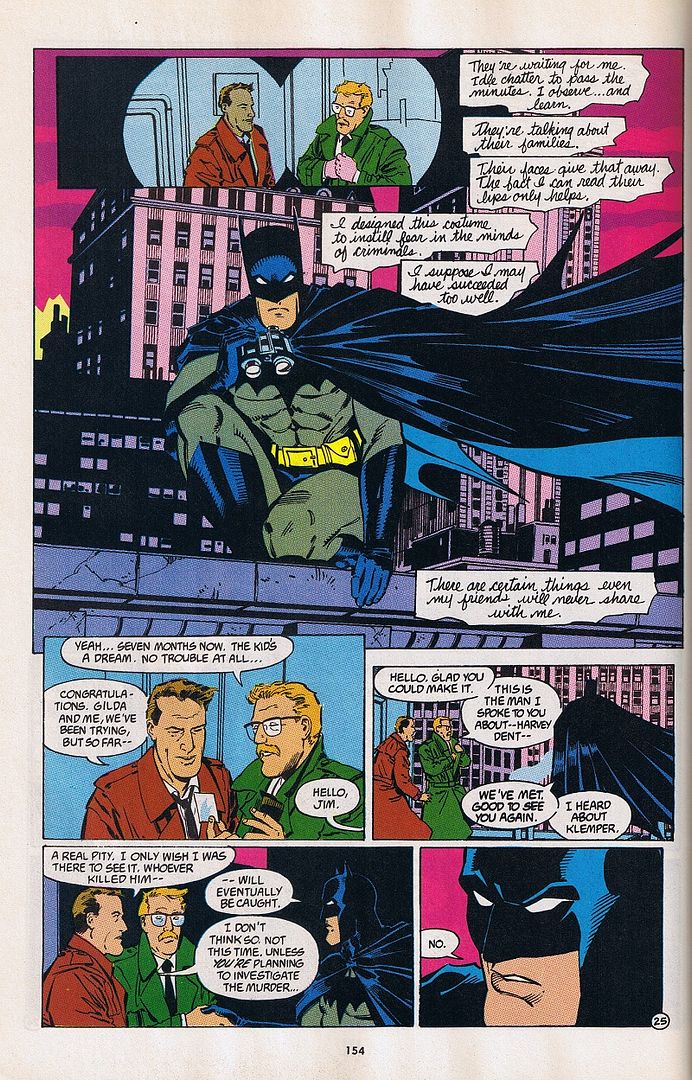

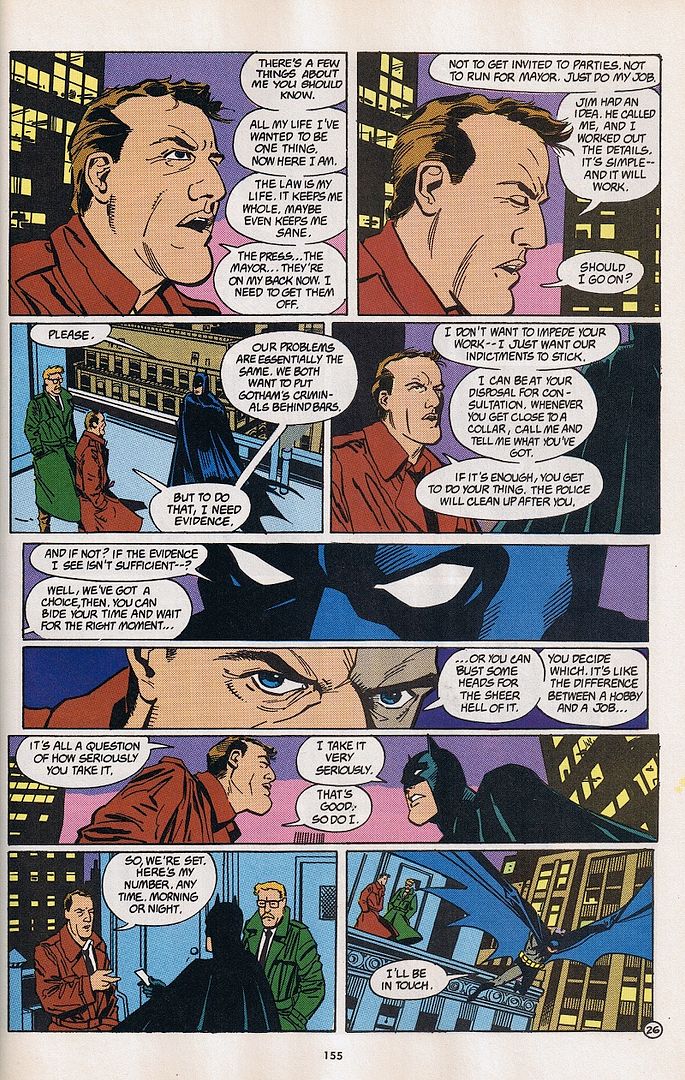

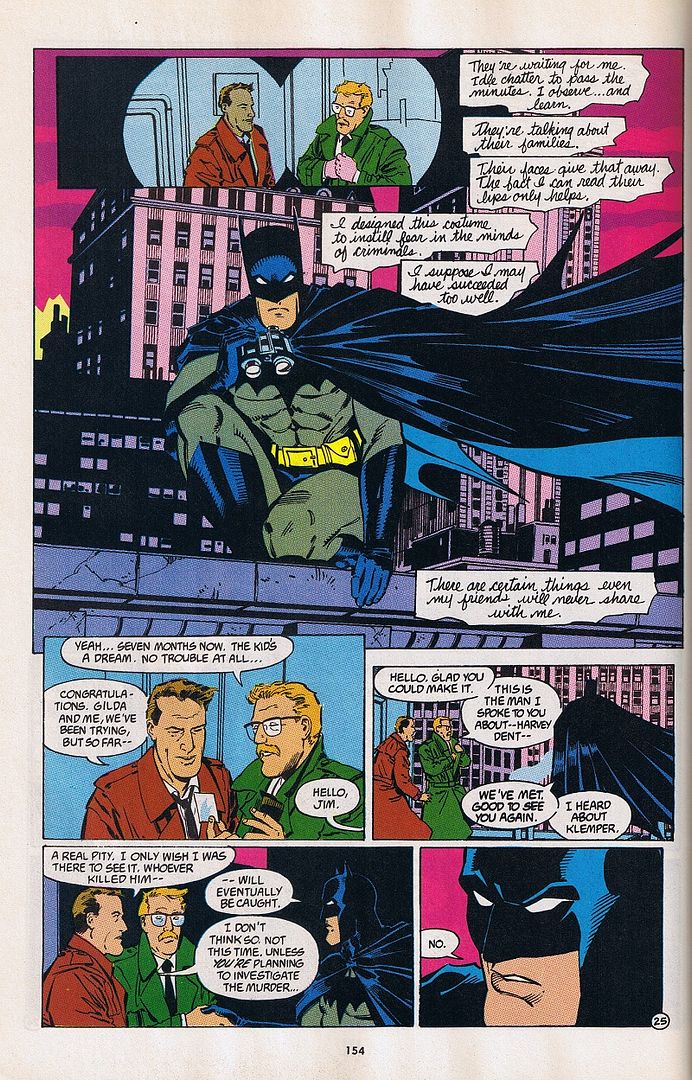

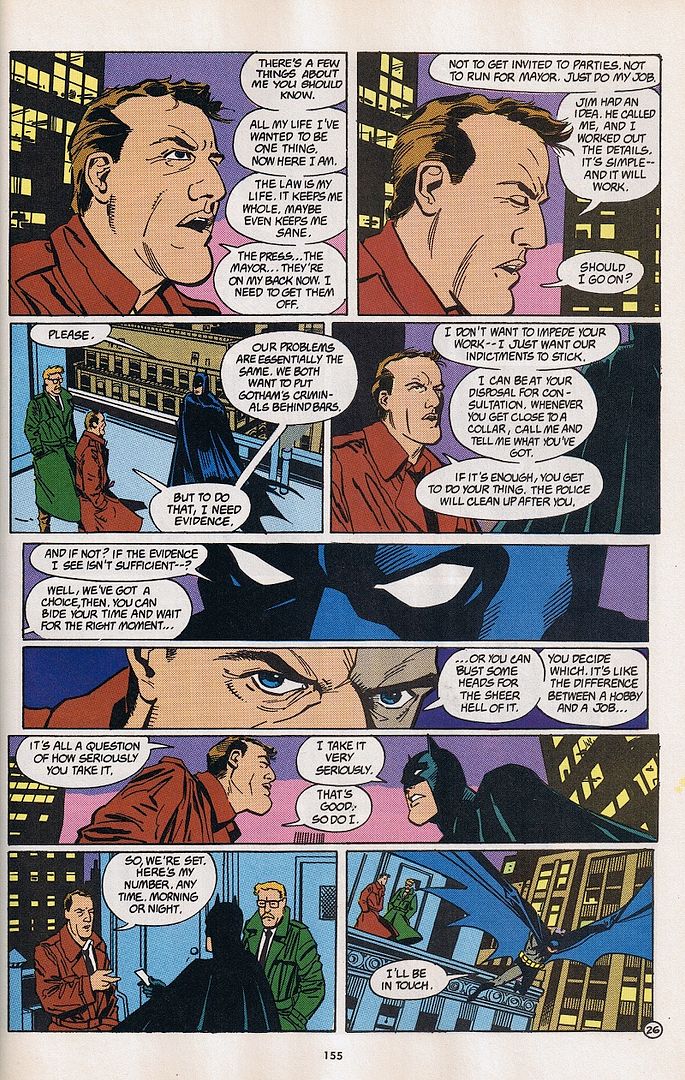

And thus we see another innovation of this story: the rooftop pact between Gordon, Dent, and Batman, as the three form an alliance to put Gotham's criminals away for good. It saddens me that most people-including Christopher Nolan and David Goyer!-credits this idea to Jeph Loeb, who famously recreated the scene in The Long Halloween. It's a novel way to reinterpret the Golden Age idea of Batman and Harvey Dent being allies for a modern era where Batman can't be an officially deputized member of the police force. What's more, it formalizes the idea introduced by Frank Miller in Year One of these three men being the sole forces for justice in a corrupt city.

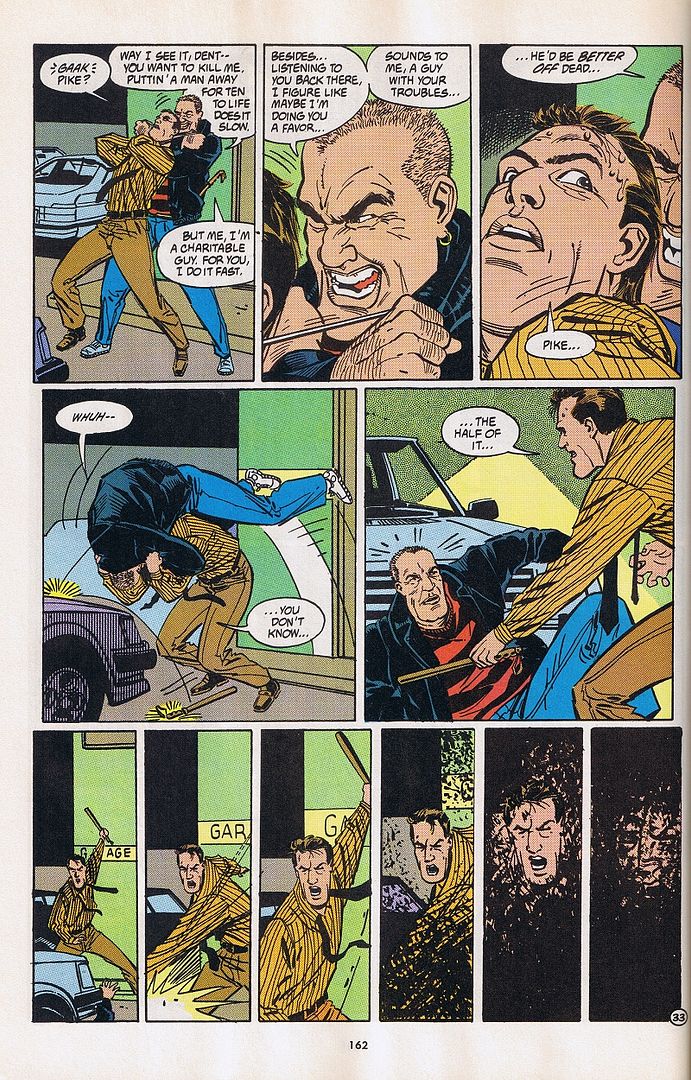

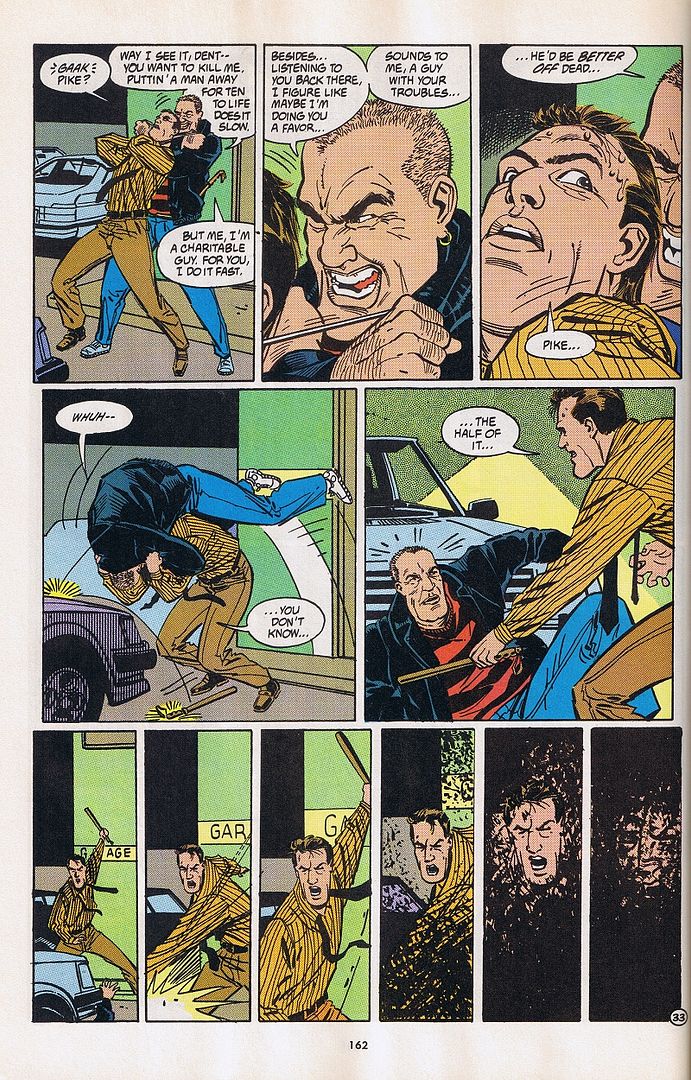

The partnership proves to be incredibly fruitful, with the trio's actions lead to eighty-seven indictments within their first month. Among their triumphs, they succeeded in exposing a towing agency car theft ring, bringing down a violent racketeer and extortionist named “Mad Dog” Pike, and they even managed to secure an arrest for “Gotham's Class-A-One psycho mob kingpin,” Vincent “The Boss” Maroni. For a brief time, everything seems to be coming up roses for law and order in Gotham City.

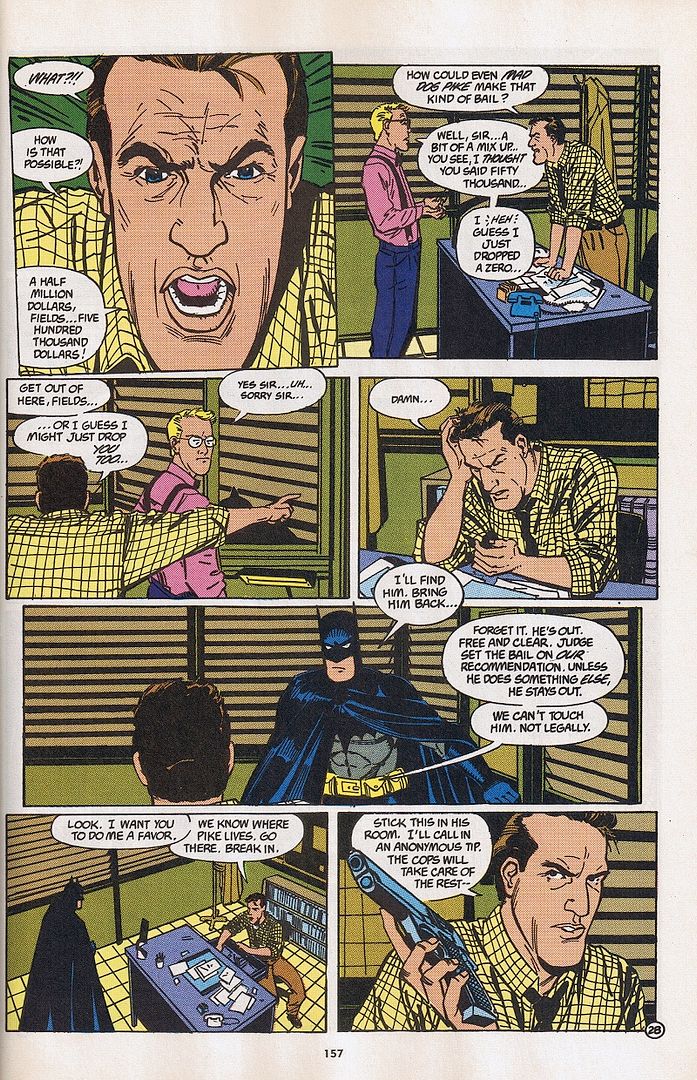

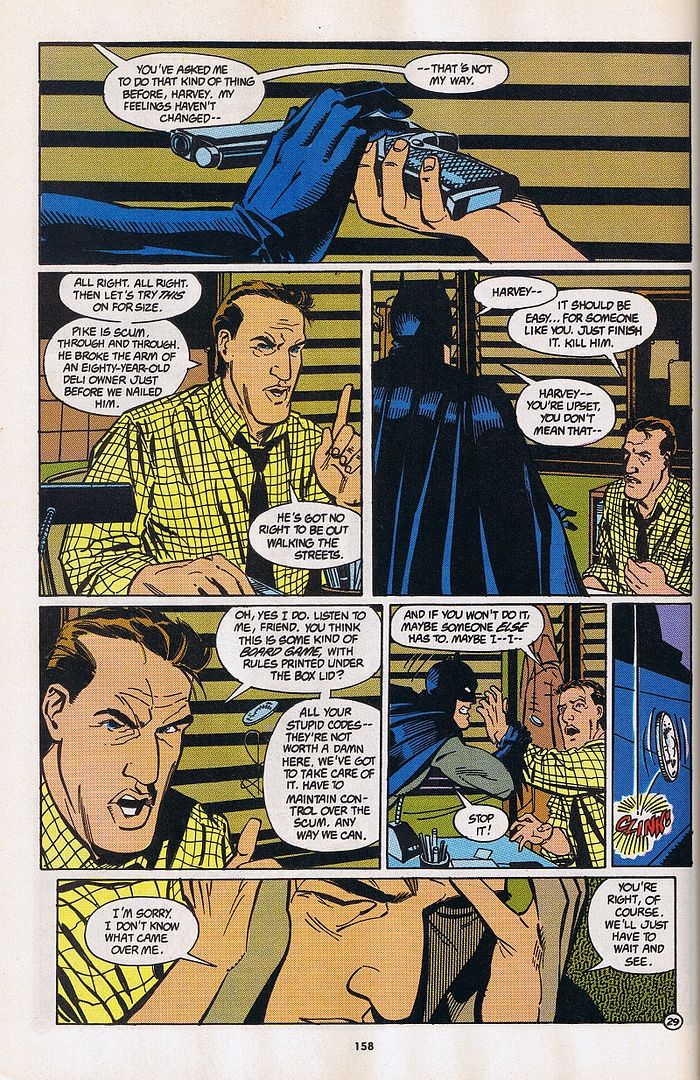

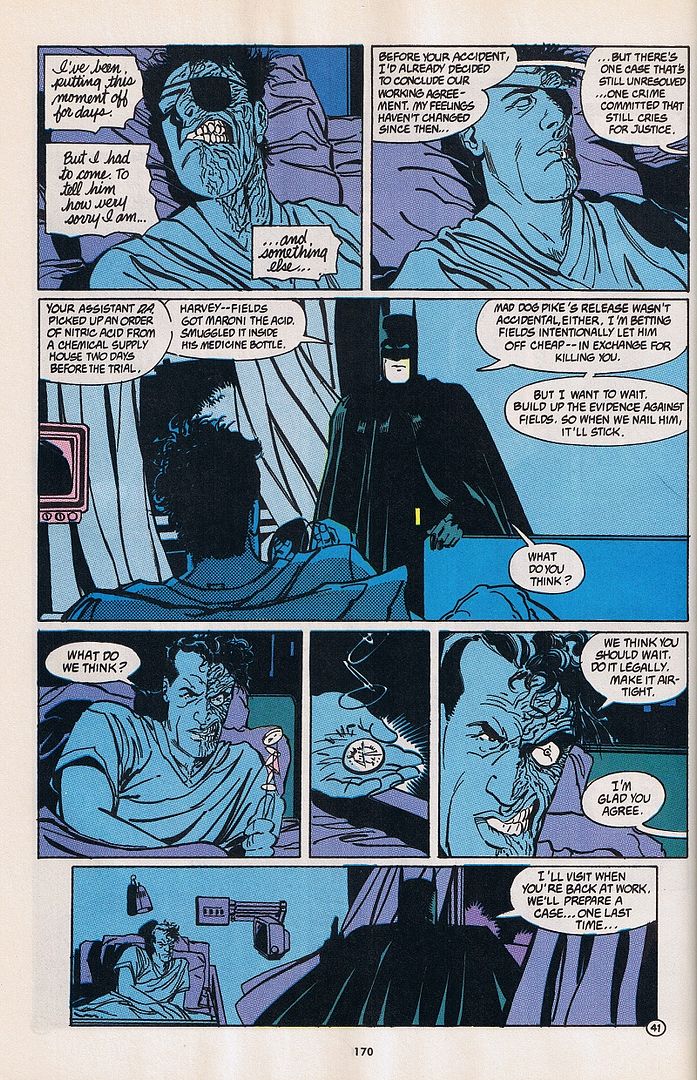

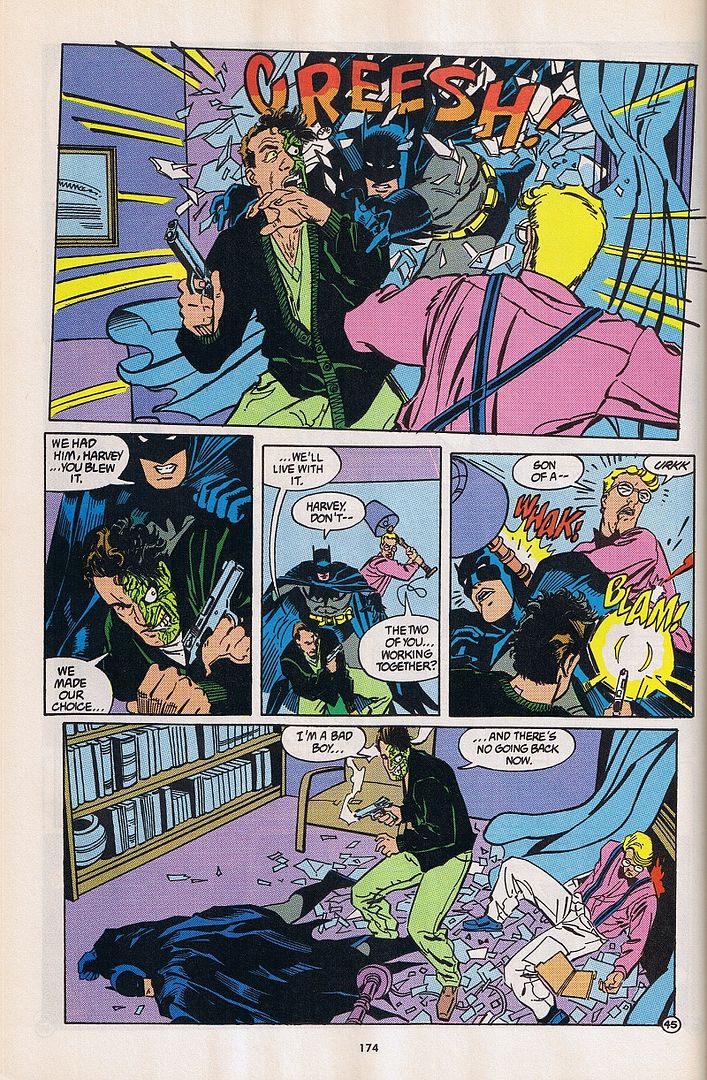

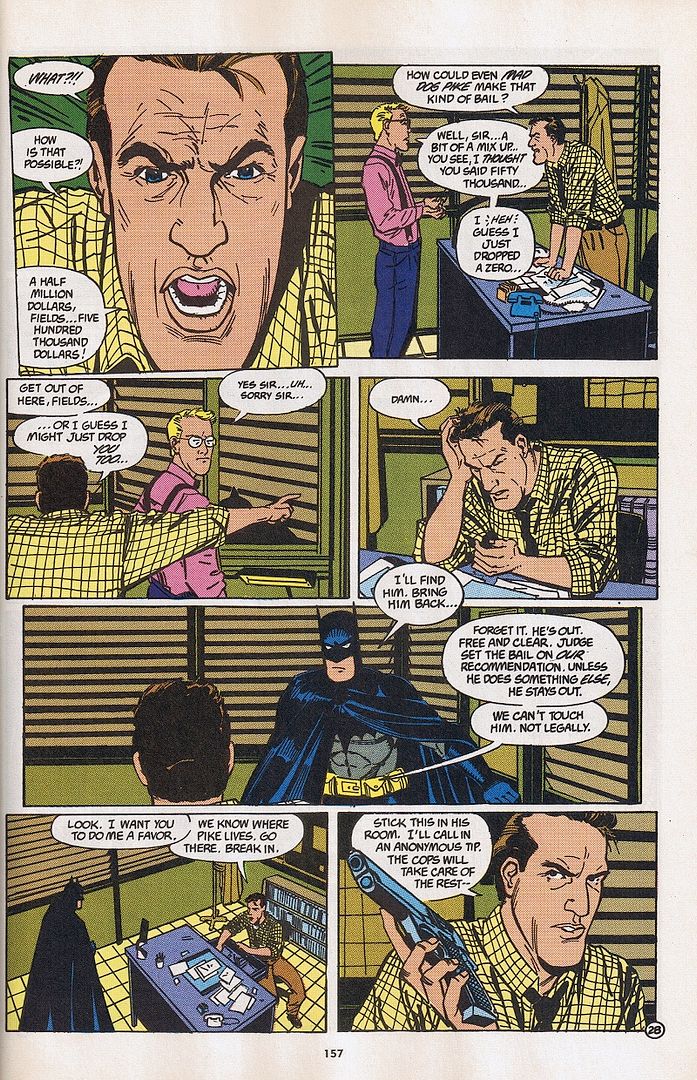

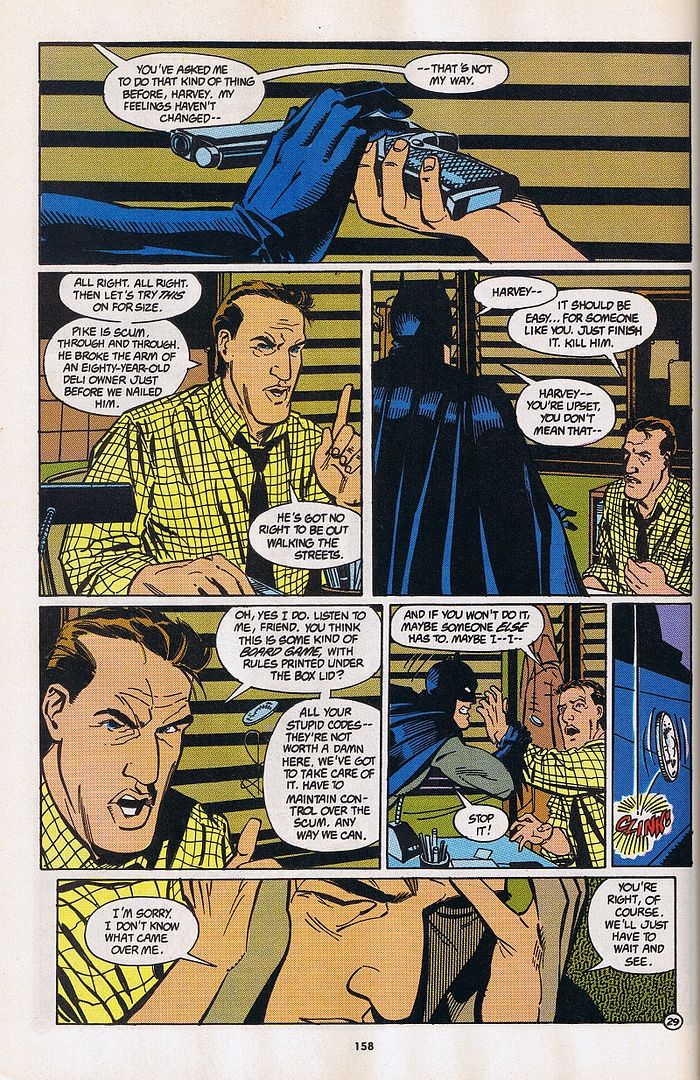

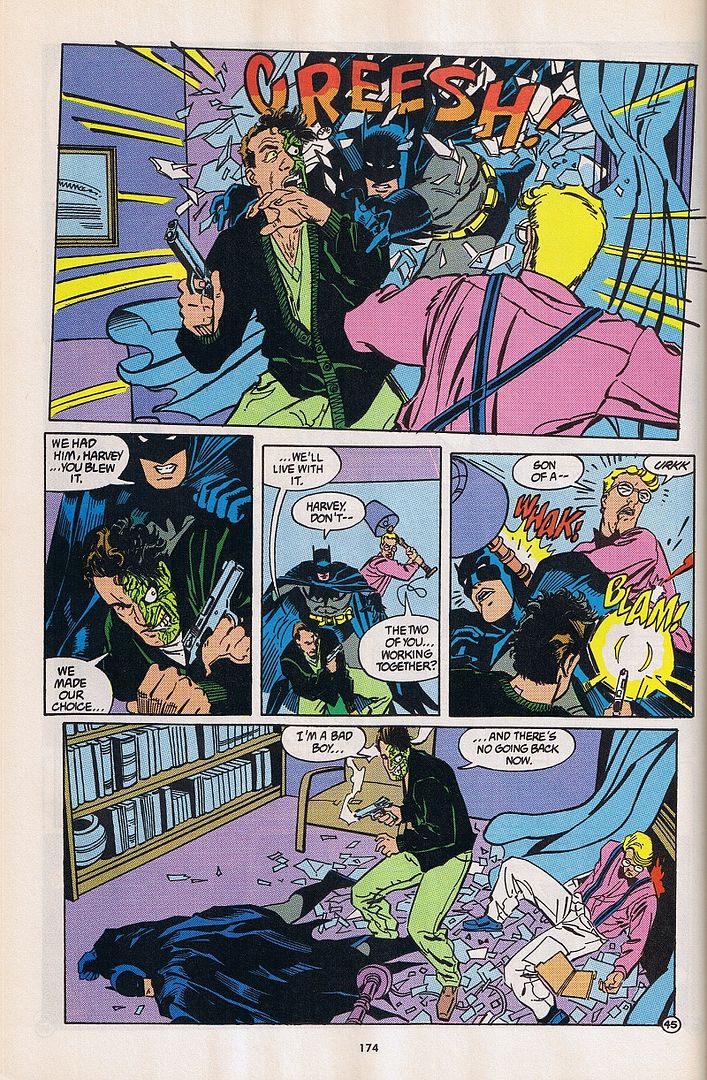

As someone who generally prefers the idea of Harvey being fervently law-abiding before he became Two-Face, I find it troubling that Harvey had suggested planting evidence at least once before, but I also find it interesting that Batman didn't break off their partnership right then and there. Maybe he just let it go because he knew that he himself operated illegally, and maybe he also forgave Harvey for being under so much pressure. This moment, however, proves to be the breaking point, as we learn when Batman meets up with Jim Gordon at home.

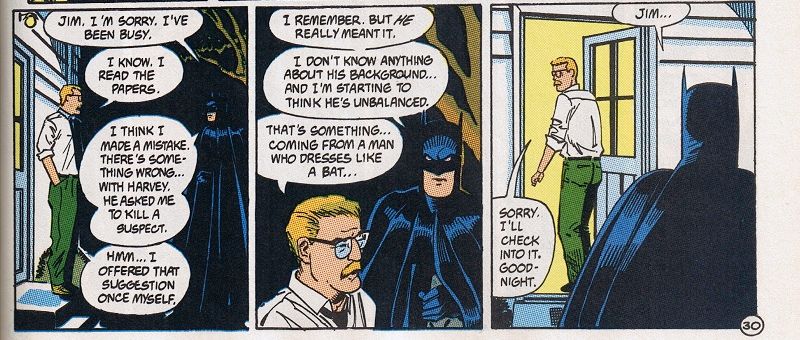

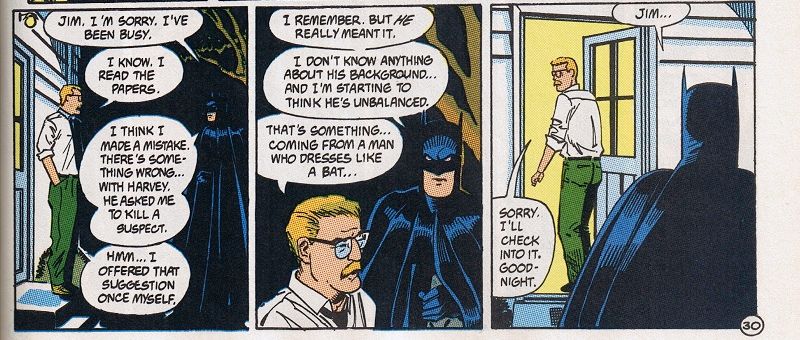

“But he really meant it.” And with that, Harvey has already crossed a line for Batman and Gordon even before he takes a life (as far as they know, anyway). While both Batman and Gordon felt the temptation, Harvey had the intent. Or at least, part of him did. That said, it's strange that it never occurred to either Batman or Gordon to check out Harvey's background before this point, especially given the rampant corruption in Gotham City. A simple check at his medical records could have saved Gotham a lot of bloodshed, and Harvey a lot of anguish.

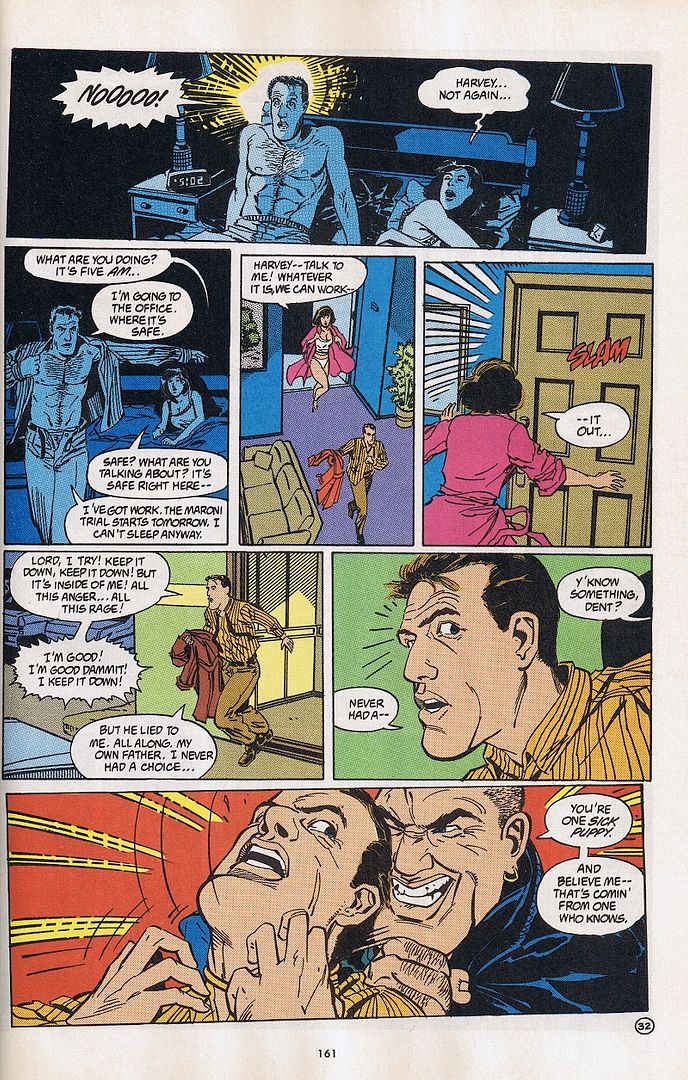

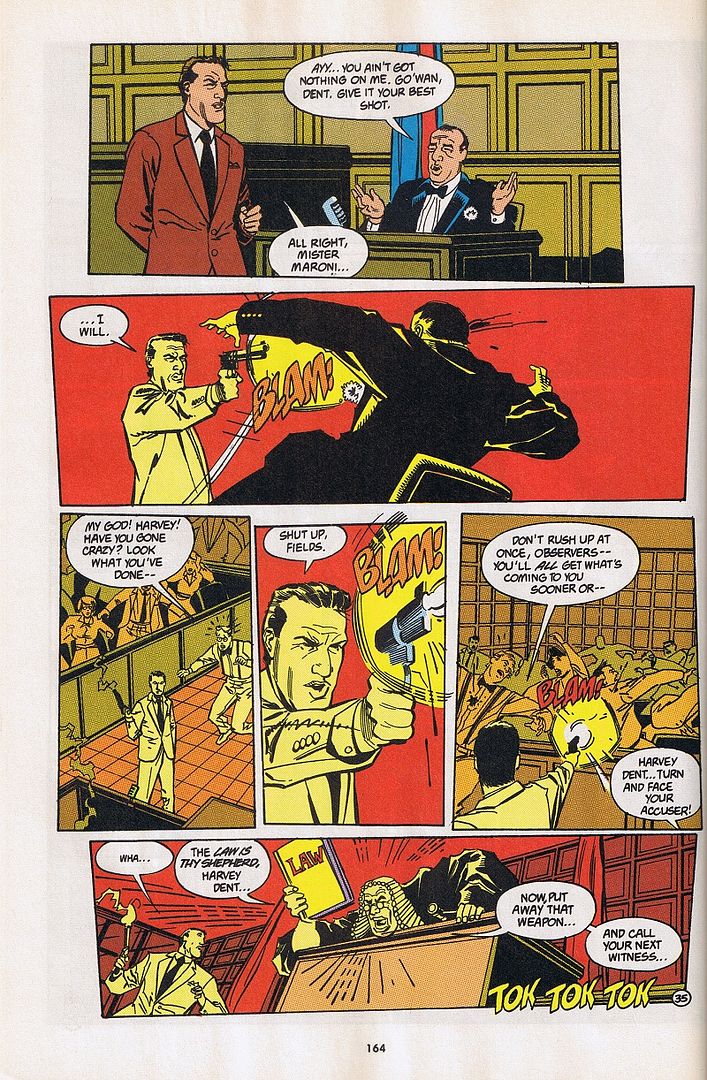

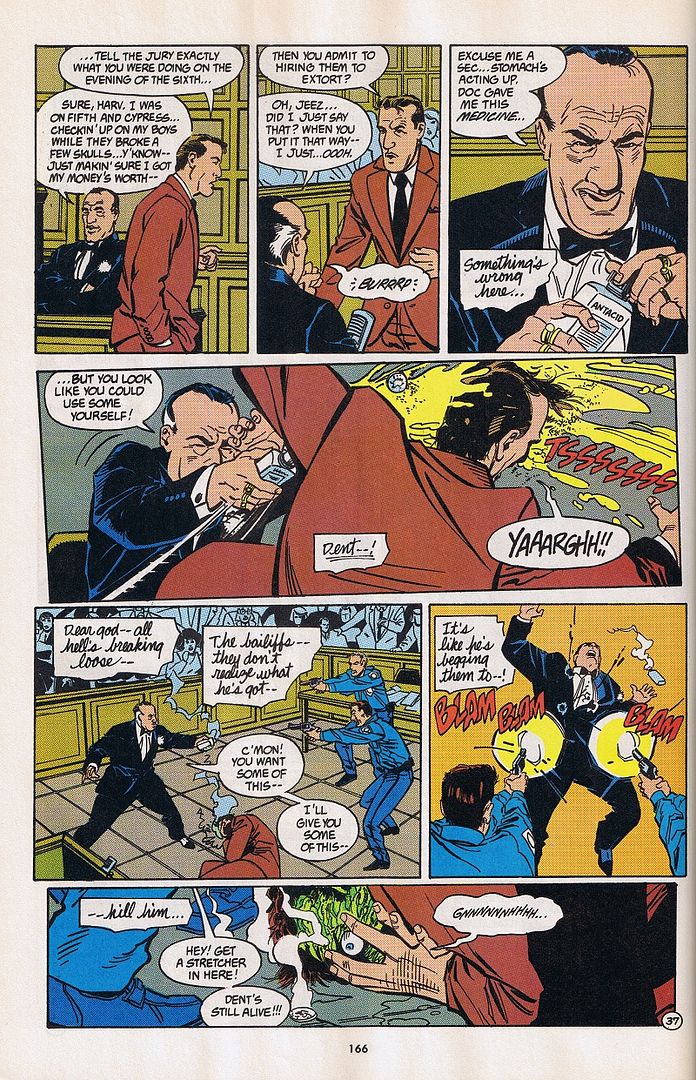

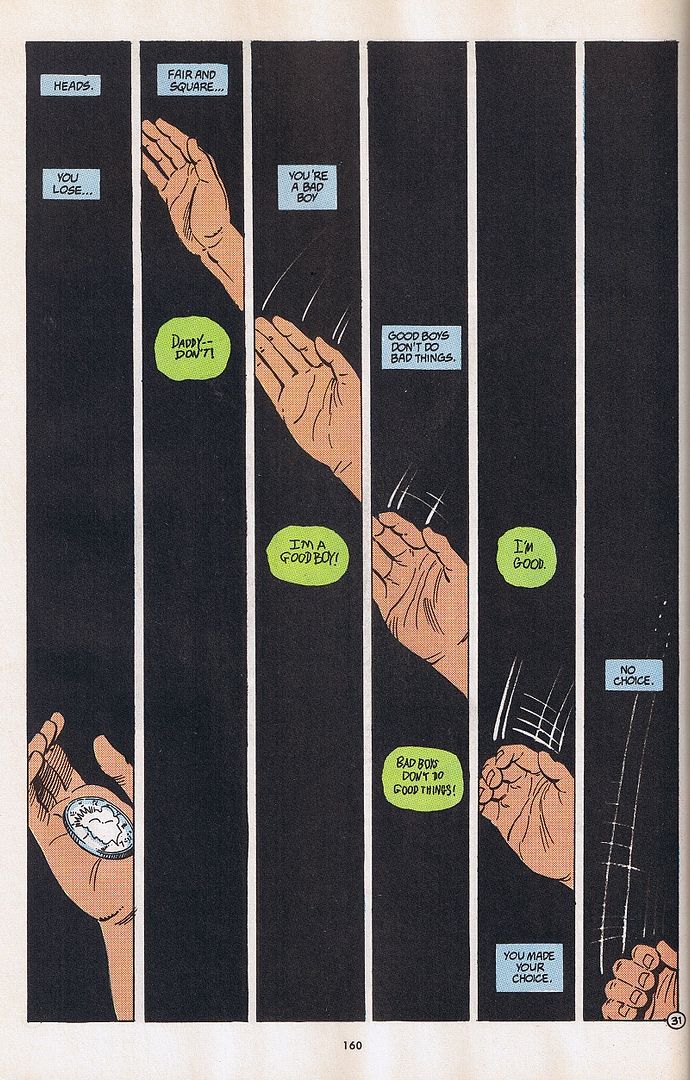

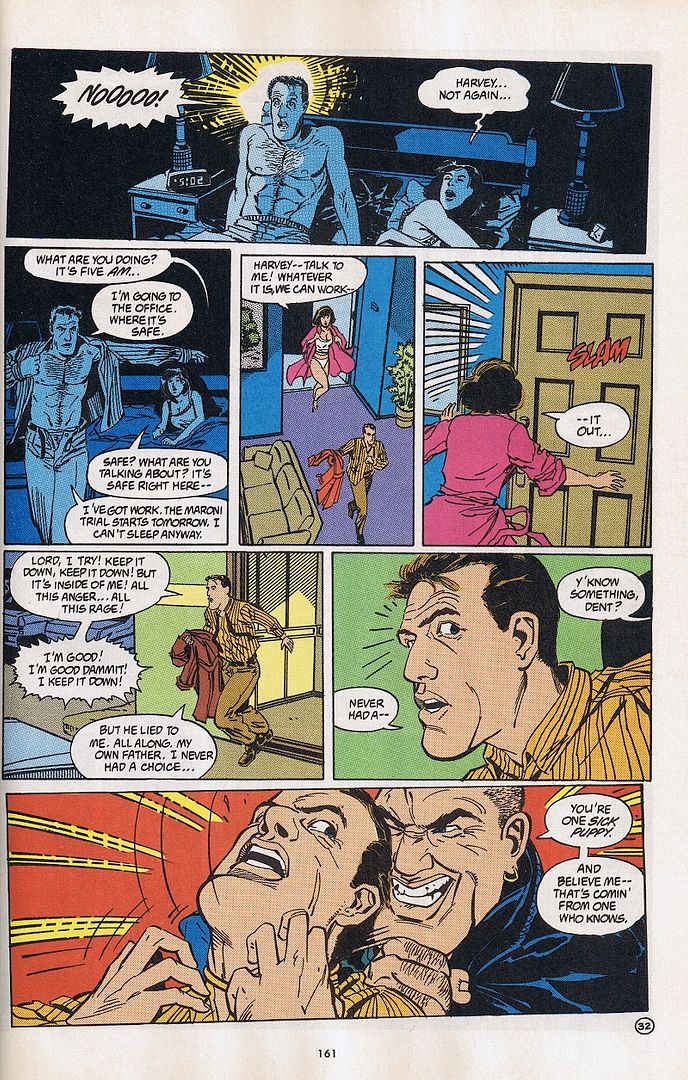

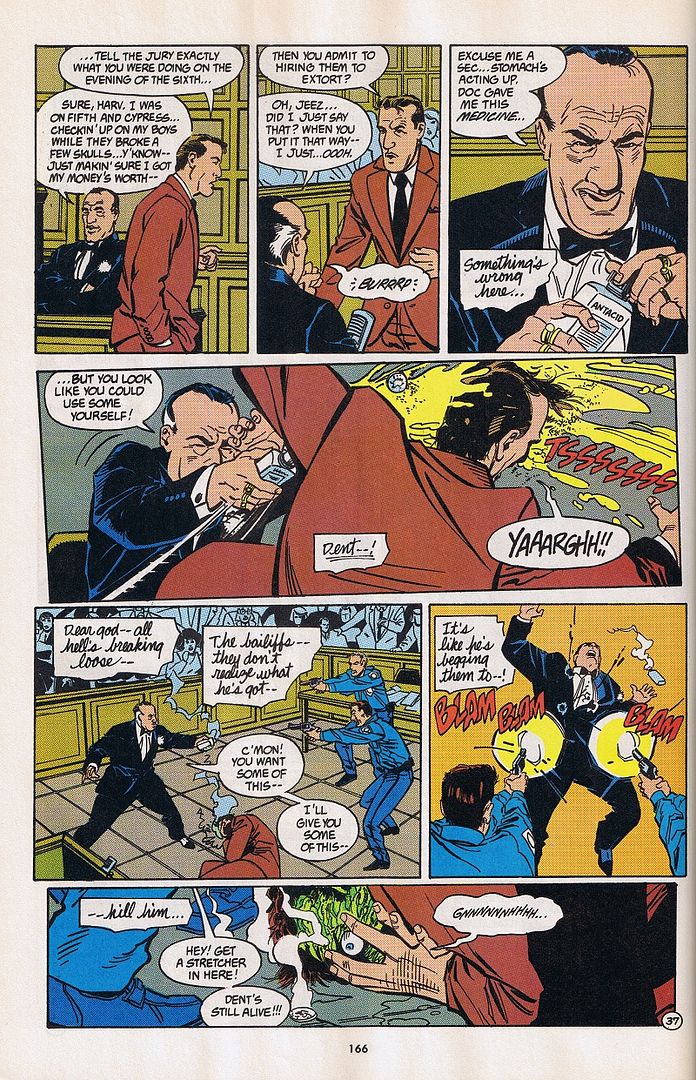

No matter how many years go by, those panels still give me chills. He just... obliterates himself through the violence. It's especially powerful to see right on the heels of the latest flashback/nightmare we've seen between Harvey and his father. Between that and his fevered rambling about the rage he has been trying to keep down, about how “good” he'd tried to be for so long, we now see that his darker side is no longer manifesting as the cool, controlled, calculating persona that plotted Klemper's death. Now, just like in Batman: The Animated Series, the other part of him is emerging in burst of the form of pure, unthinking rage. Almost like the rage of a child.

The fact that he wants to shield Gilda from himself is poignant, because he's trying to keep himself in check just long enough to protect the only person he loves. It's a shame we don't get to see more of their relationship here, considering how she's traditionally been the only person who can reach Harvey through the madness. Sadly, this isn't a story where Harvey gets to be saved, not even temporarily.

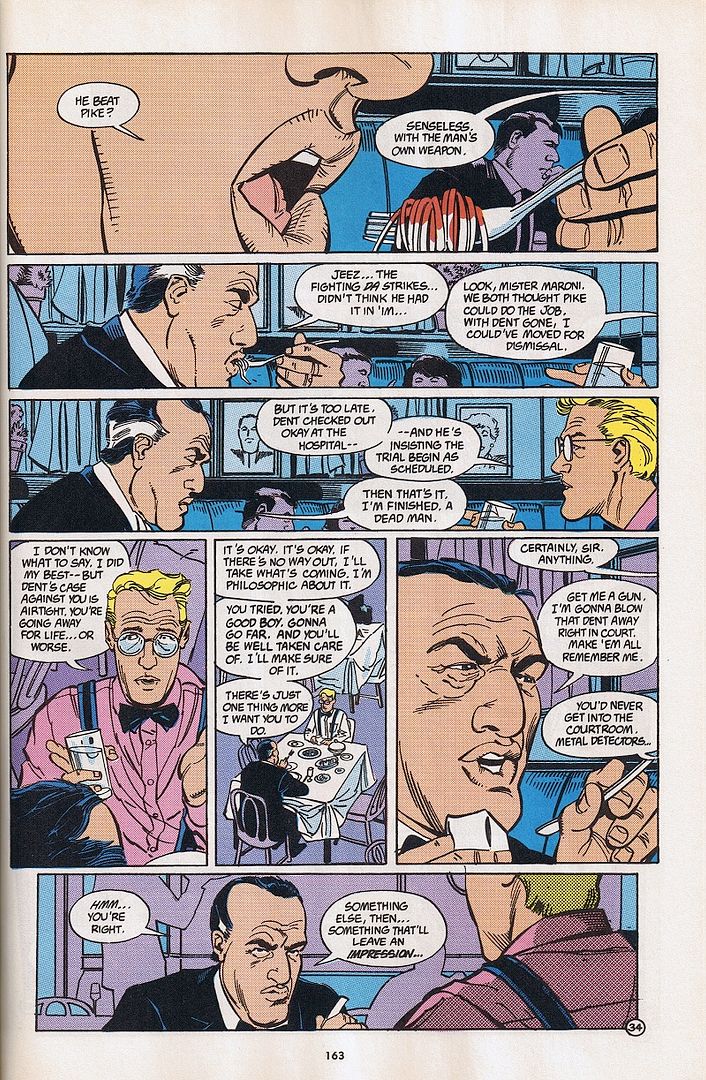

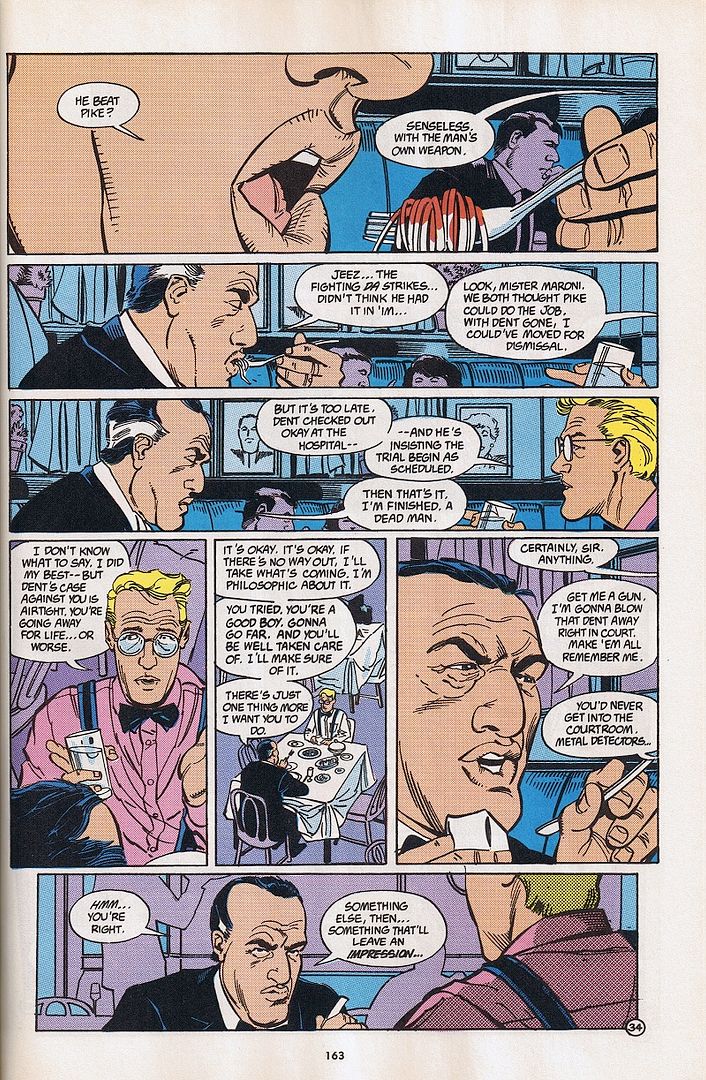

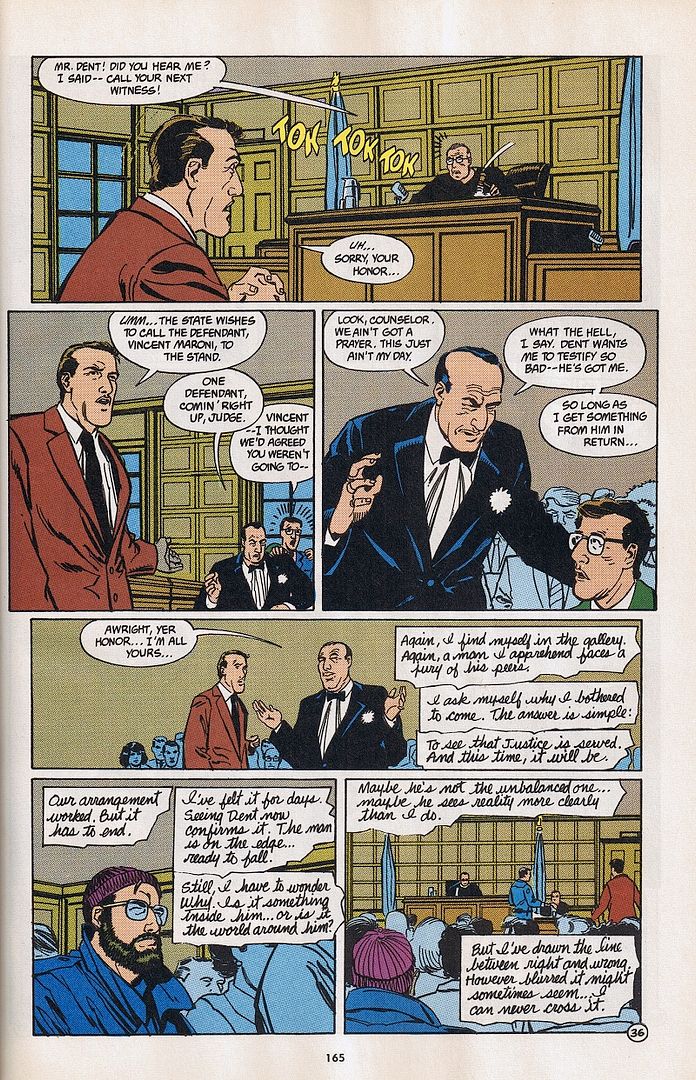

Not only do we learn about Fields' double-dealing (sorry, sorry, I promised no puns), but we also finally get to meet up with this story's version of Vincent “Boss” Maroni right before his big moment. It's a little strange to see that Maroni isn't a bigger deal in this story, that he's presented as less of a nemesis for Harvey and more just a particularly notable suspect to cap off the trio's considerable pile of accomplishments. He's less of a character here and more just a plot device dressed up as a mobster cliché, right down to the tuxedo, which works just fine for this story's purposes. At this point, he's just here to play his part.

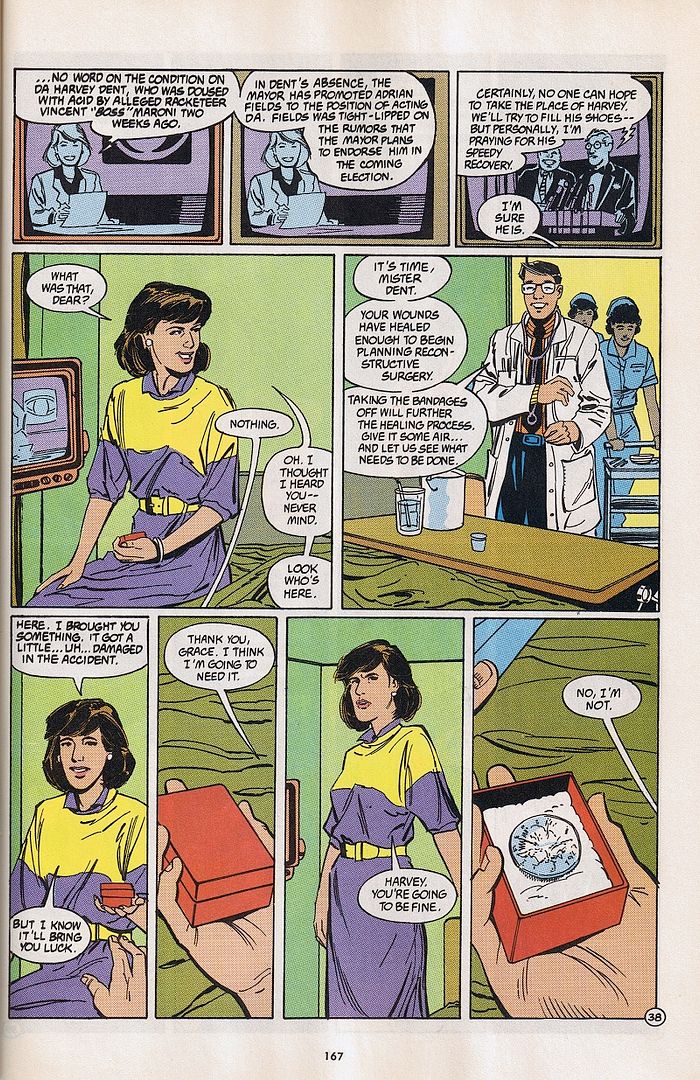

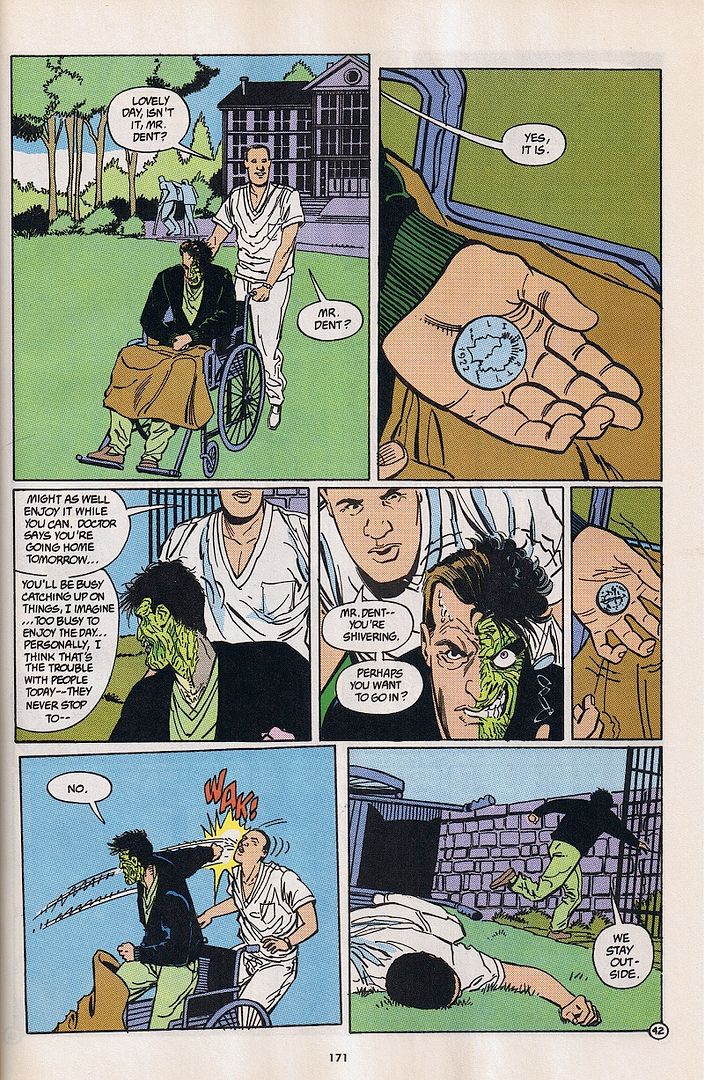

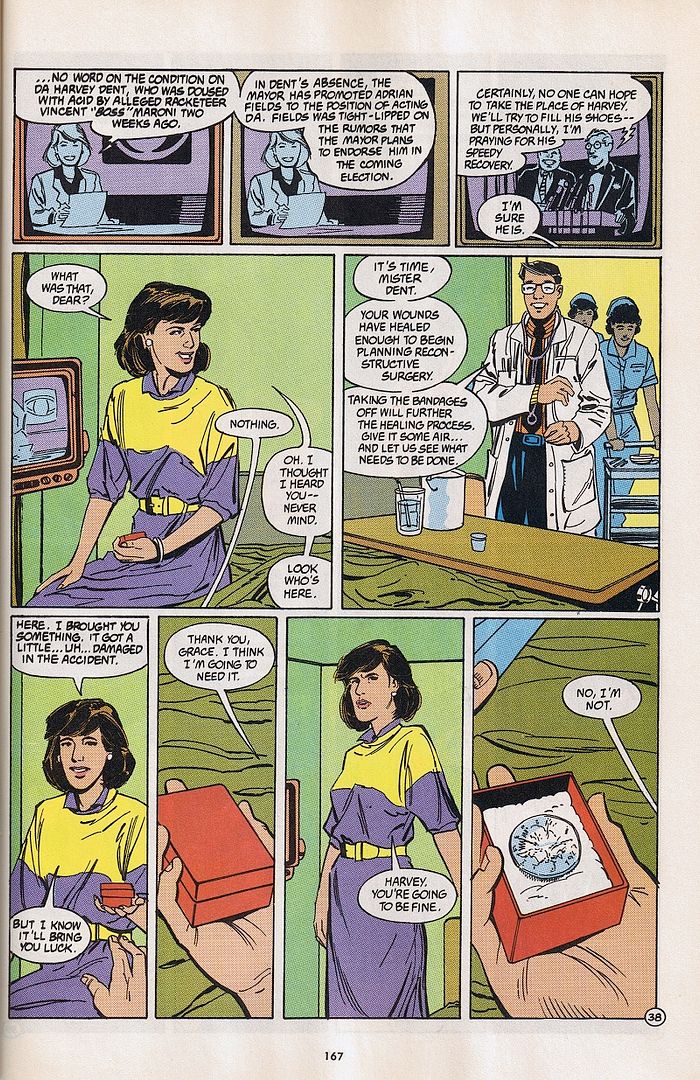

Notice that Harvey called Gilda “Grace,” which is the name she'd been given in Secret Origins Special. Putting that odd slip-up aside, this is a moment which-I'm sorry to say-I can't really justify. Why in God's name would she think that it's a good idea to give Harvey, especially a Harvey in this kind of raw emotional state, the coin given to him by his abusive father?

Considering that Harvey had been fiddling with the coin openly over the past seven months since this story began, maybe she thought that he'd now made it his own good luck charm or something? If so, then that's all the more reason we should have seen more of Harvey and Gilda's domestic life. And even then, it's still a pretty shitty good luck charm, unless you consider it good luck that Harvey survived the attack and didn't even go blind.

Also, I think it's rather inspired to have had the coin scarred from the acid rather than by Harvey's own hand. Considering what the coin means to him and how it was used against him, finally, after all these years, the game is fair.

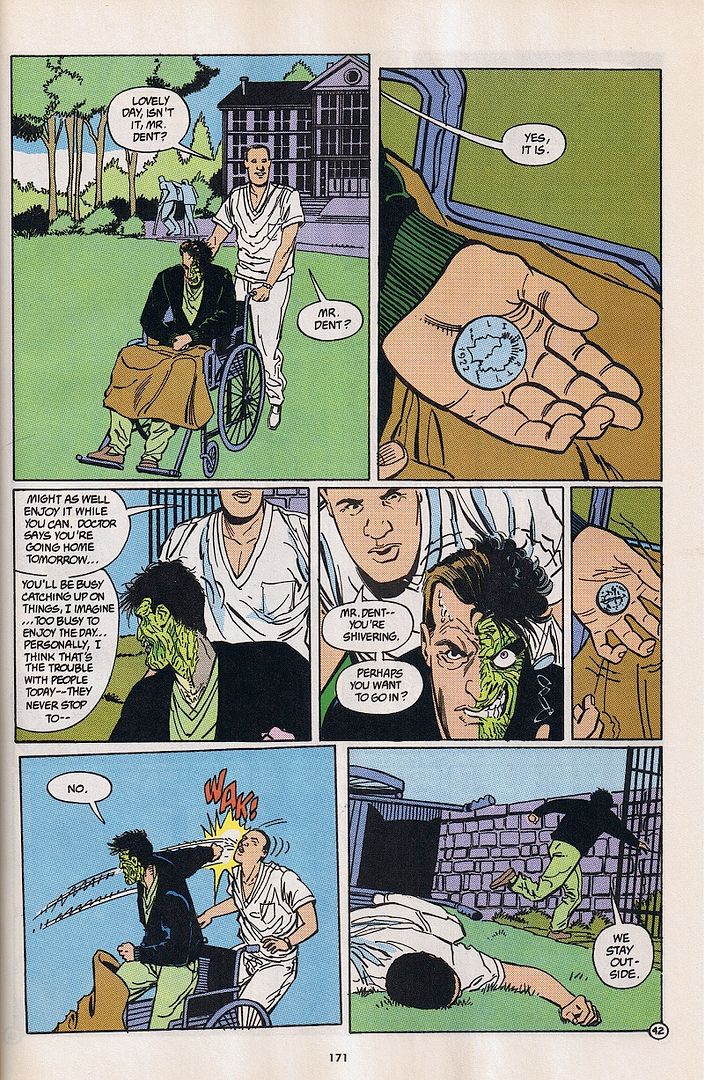

At this point, I'd like to mention that DC produced an official, gloriously awful audio dramatization of this comic, with the adaptation of this scene being a particular highlight. Seriously, give it a listen for yourself and try not to fall out of your chair when you hear that actor's rendition of “NO! WE STAY OUTSIDE!”

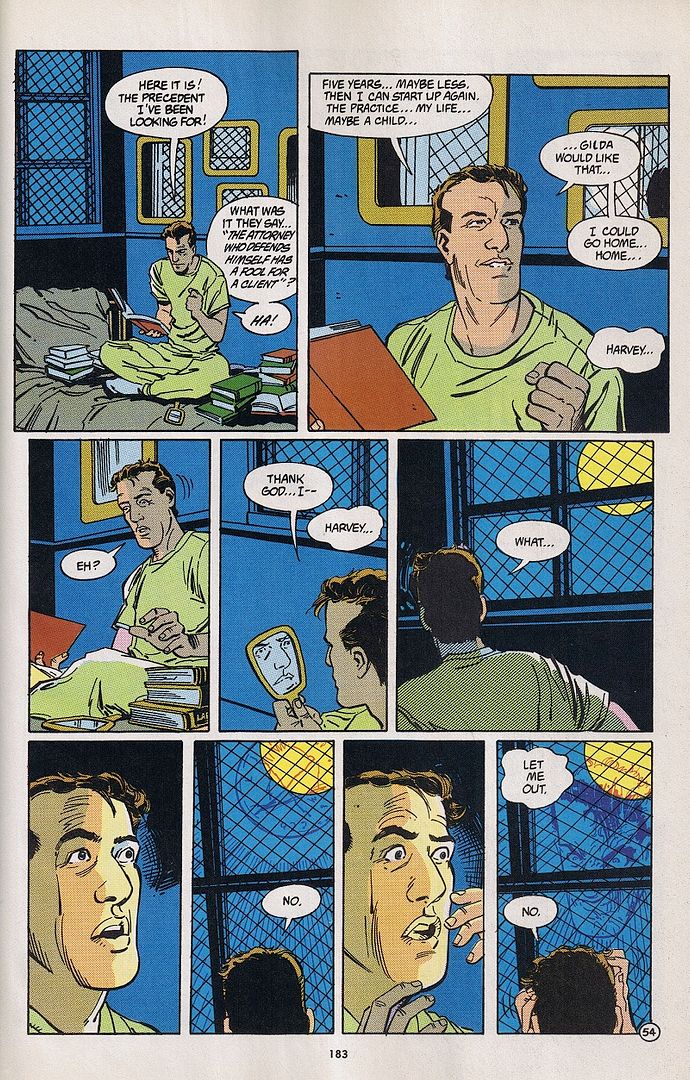

In all seriousness, though, it's worth noting that this is the first story to have Harvey speak of himself as a plural, an idea which I've noticed has been met with some contention. I personally don't mind it for this story, especially since the simultaneous presence of both Harveys is key to the confrontation at the end. But first, Harvey needs to pay a visit to his old assistant, who's already moving up in the world, the little weasel.

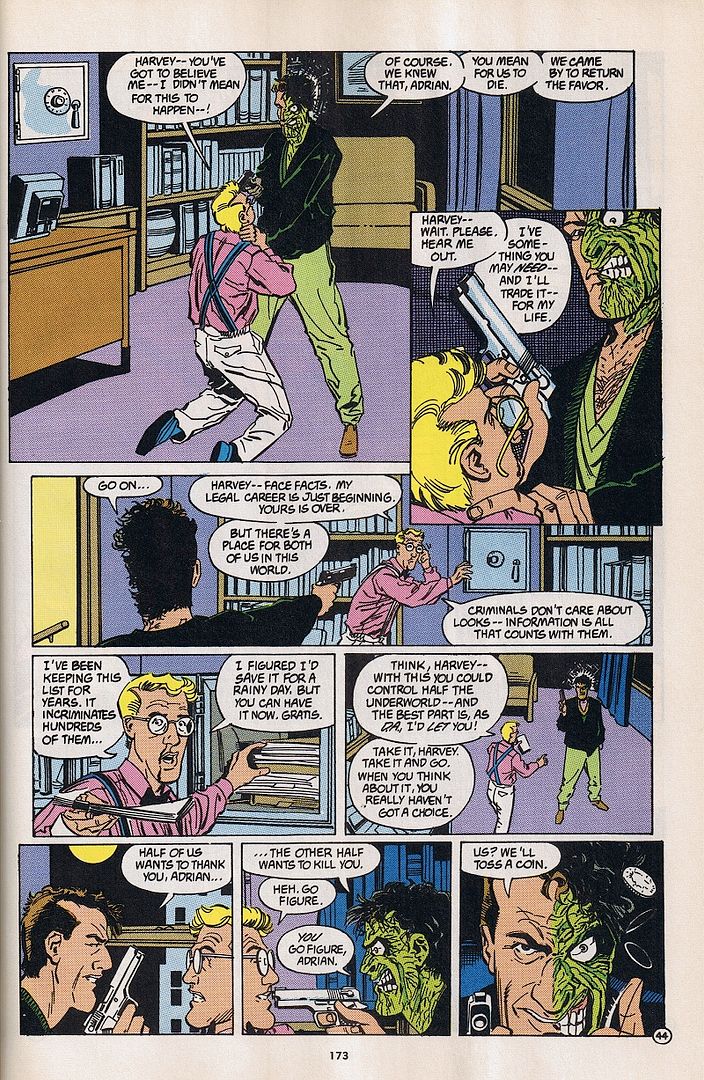

With this handy-dandy super-file, we're given a convenient explanation for how a District Attorney somehow managed to reinvent himself as a powerful criminal mastermind. It still doesn't really explain why Harvey would actually want to become a powerful criminal mastermind, but then, most Two-Face depictions suffer from the same lack of motivation.

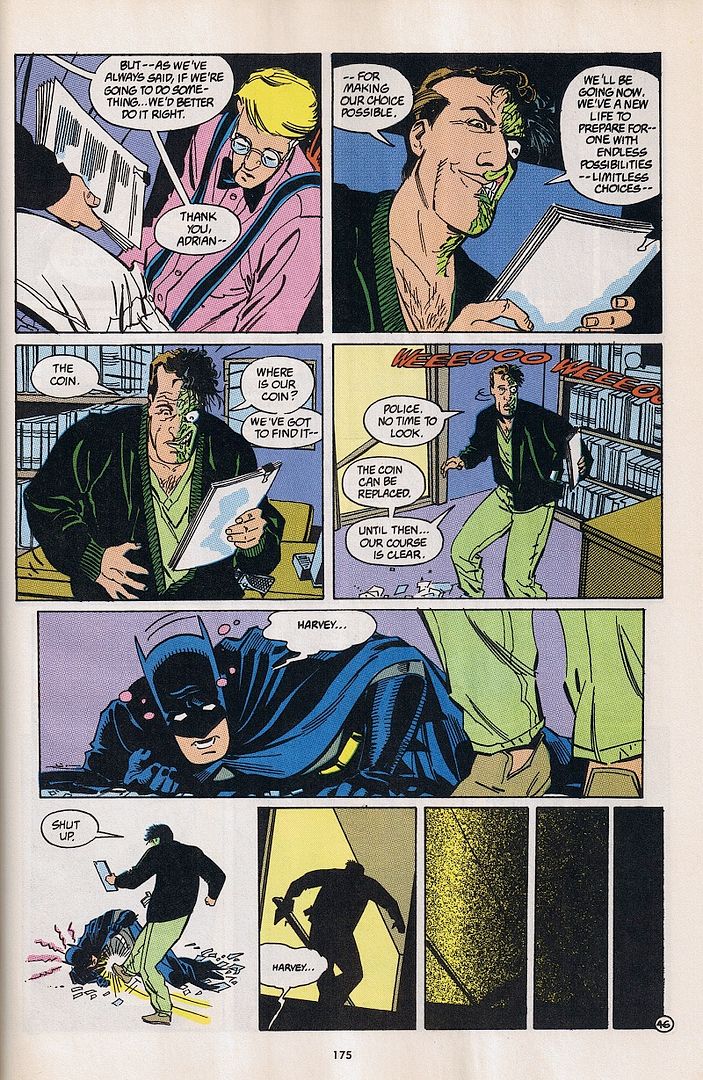

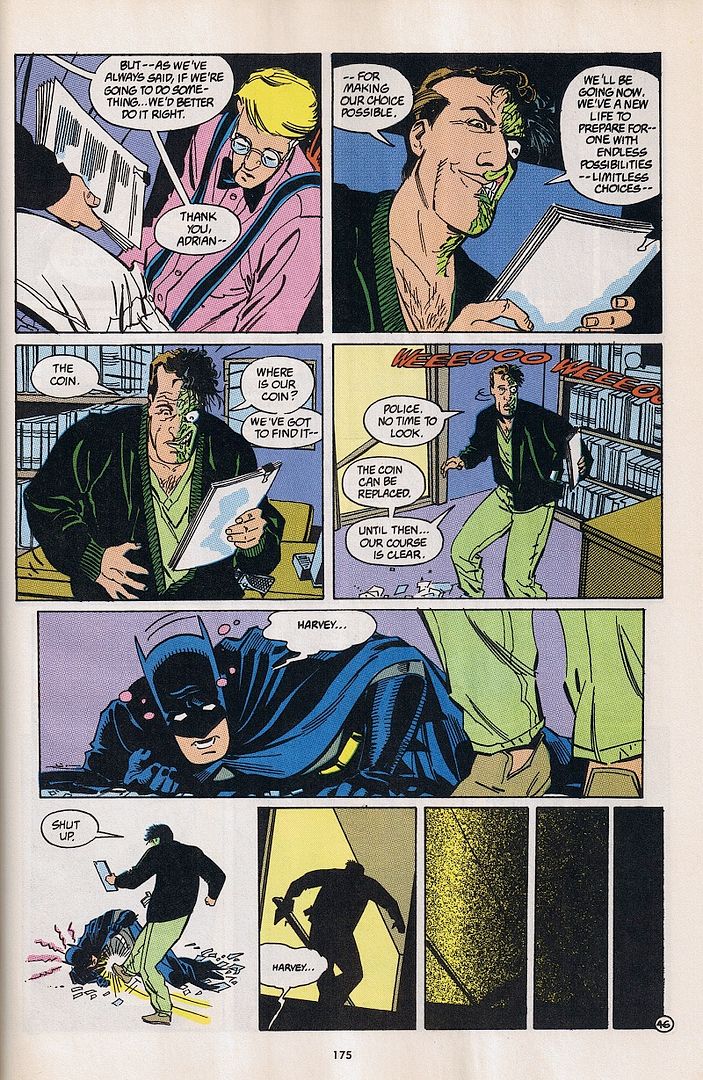

If I had to guess based on what we see here, I suppose that he's drawn to the criminal life because of the freedom it promises, “a new life... with limitless choices.” Even as he's given up his free will to the dictates of a coin toss, he paradoxically still seeks the freedom of choice. Whether or not any of this makes sense, it'll have to do as motivation until some writer someday comes up with a better reason as to why Harvey made the conscious decision to become everything he ever hated as D.A.

Before you mention it, yes, I know that hebephrenic (AKA disorganized) schizophrenia doesn't really resemble whatever mental illness that Harvey has. It's nice of Helfer to try bringing real-life mental illness into this, but it doesn't really work, unless we somehow accept that his adolescent schizophrenia somehow mutated into his current disorder. Trying to nail down what that disorder is may be impossible, especially given how much of it is tied up in the trauma that Harvey suffered, the exact nature of which is only now starting to be revealed.

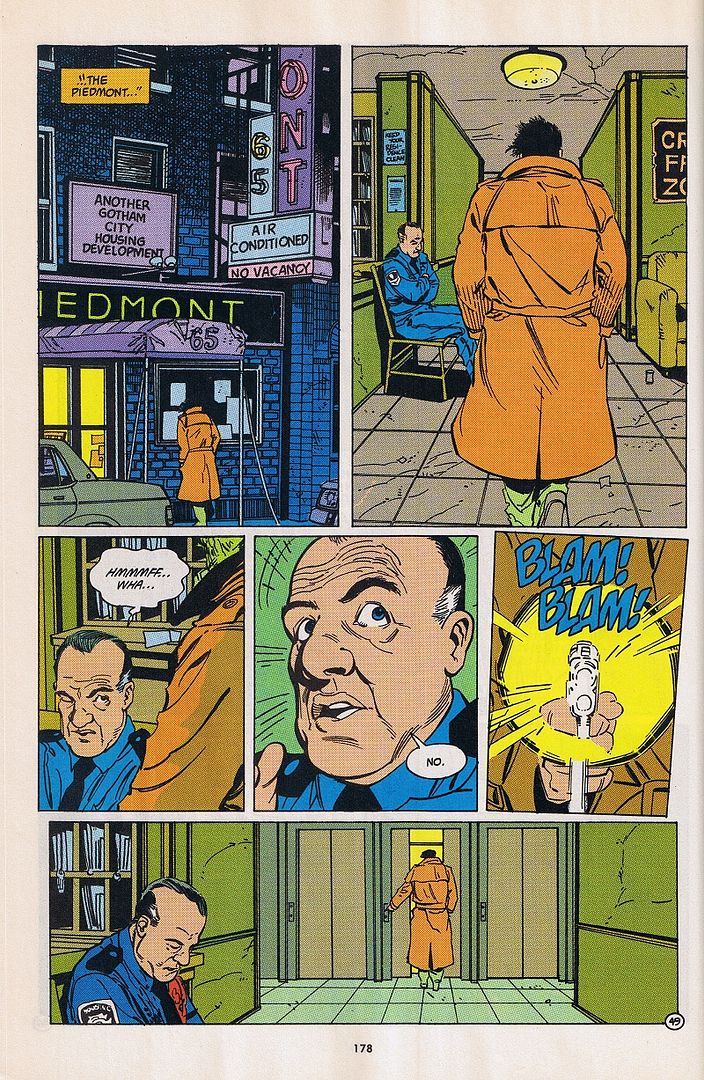

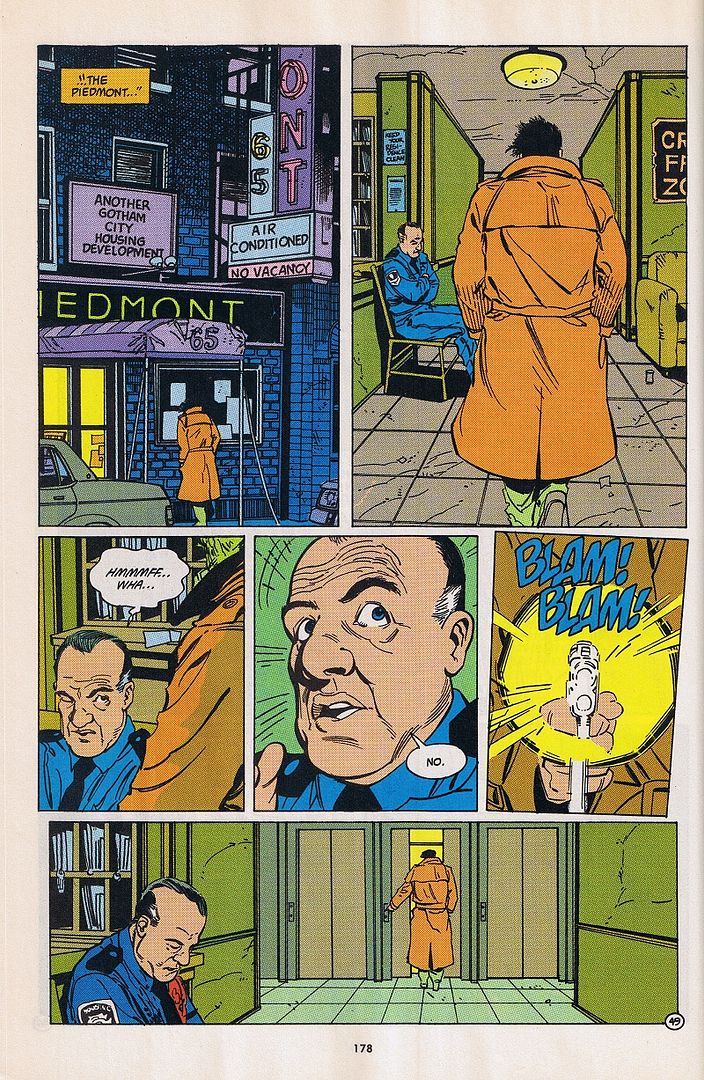

He's now so far gone that he just casually killed that guard in cold blood. Honestly, I think that was a bit unnecessary, especially since he didn't even flip for it. He could have just as easily knocked the guard out with the butt of the gun and it wouldn't have changed the story a bit. It's important to know that the good Harvey isn't entirely gone, especially now that both Harveys finally confront the monster who made them.

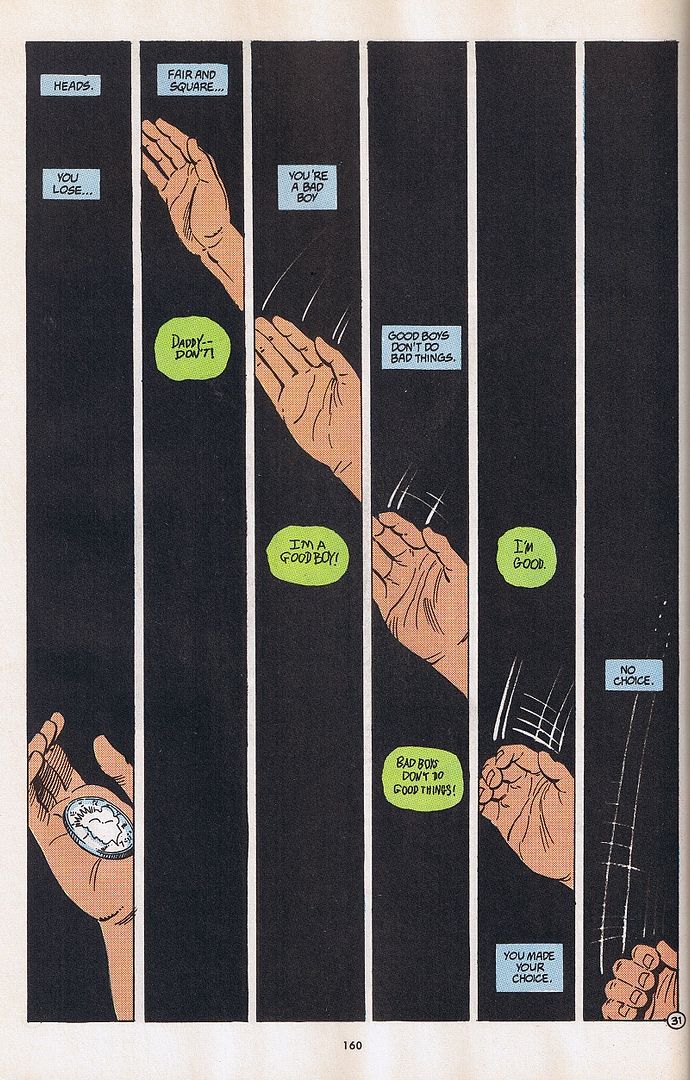

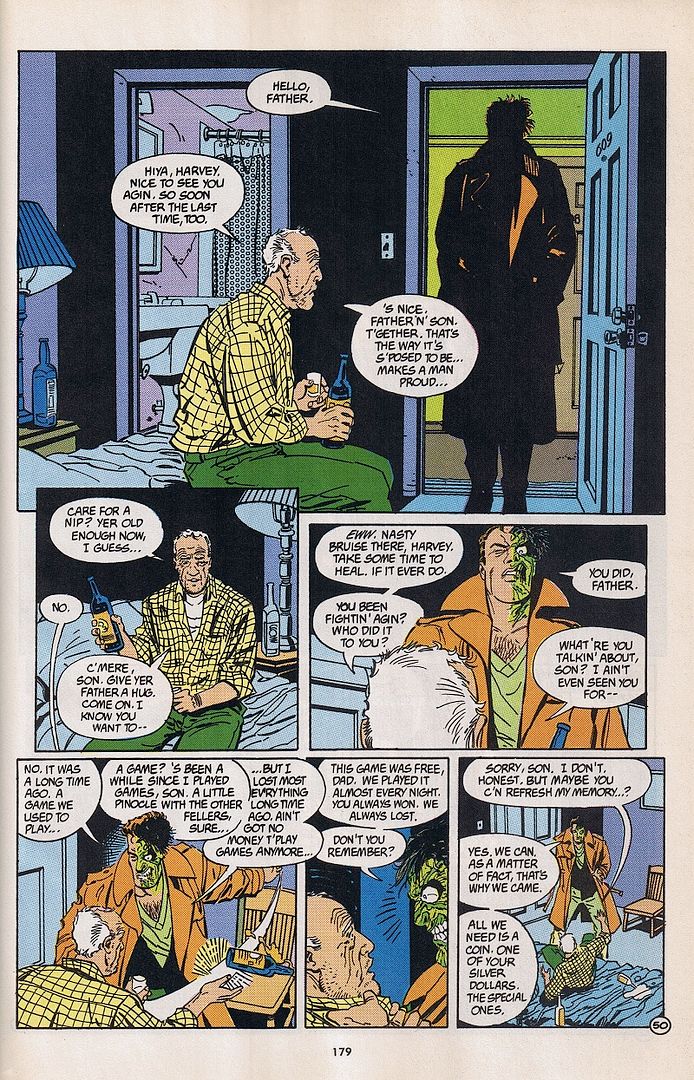

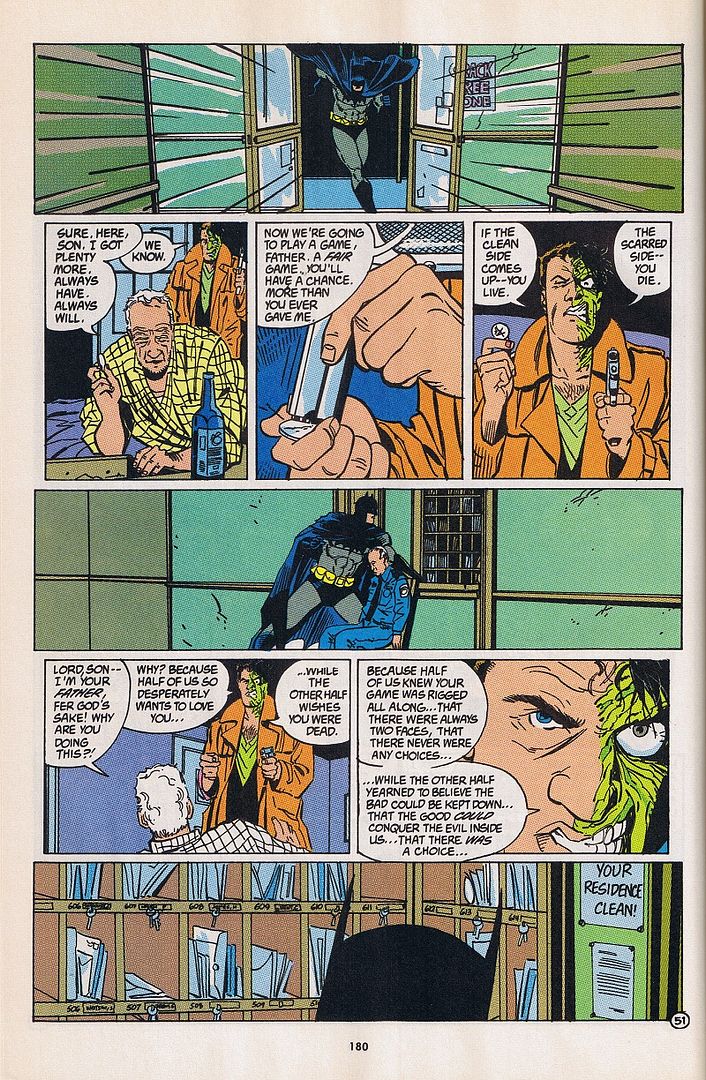

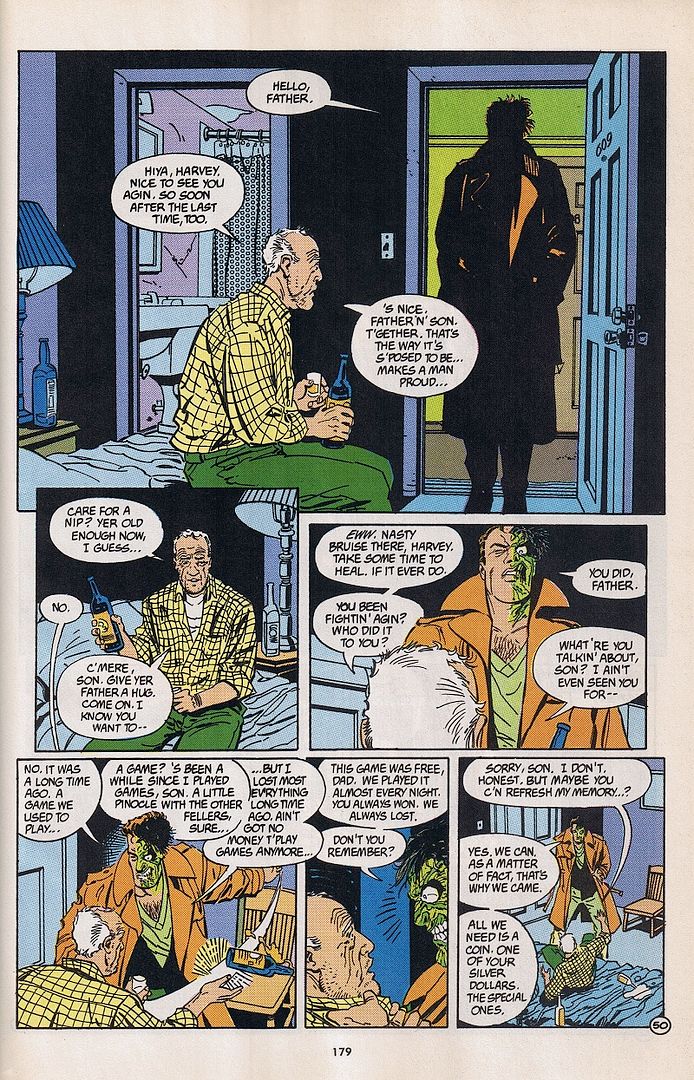

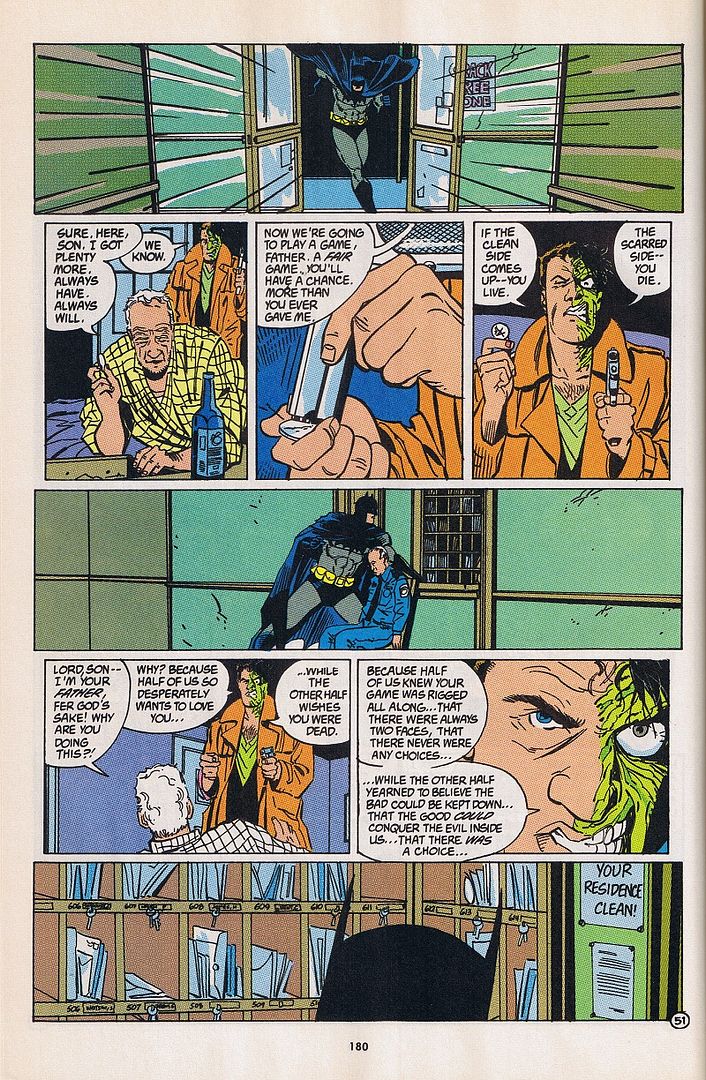

And here, finally, we learn the true extent of his father's abuse, and how it's turned Harvey into the men he is today. This, right here, is why I'm annoyed by all the other stories and Who's Who and Secret Files profile pages that mention Harvey's abuse without delving into the exact nature of the game itself.

It's not enough that Harvey was physically abused, but his entire psychological state was warped by the game, to the point that he was constantly being torn apart between love and hate. Namely, the love of his father, who he trusted to play fair, and the burning hatred from the part of himself that knew, deep down, that the game was rigged and that his father was just making up excuses to beat him.

Speaking only for myself as the son of an abusive alcoholic, this internal conflict hits very close to home. My father used to play all sorts of mind-games that caused me to doubt my own memory, making me worry that I was overreacting when I tried calling him out on his behavior. I ended up having to shove my anger deep down inside, just on the off-chance that I was in the wrong, even though I knew in my heart of hearts that I wasn't. And yet, a part of me wanted to believe that I was wrong, because I loved my father with all my heart, and I didn't want to think of him as some kind of lying monster.

The only story that comes close to capturing this internal struggle is Two-Face: Crime and Punishment, which abandons the game in favor of the far more commonly-understood abuser logic of Why Did You Make Me Hit You? (Warning: TV Tropes). It's a powerful take on the character, one which turns Harvey's dark side into a destructive force of both twisted self-preservation and self-loathing, but I still prefer the “game” origin because of the significance it gives his every coin toss as Two-Face.

This Two-Face isn't flipping the coin to choose between abstract concepts of "good" and "evil." After all, those ideas are just so subjective and fluid, all to easy to twist and cheapen, as many lesser writers are wont to do. He's caught between two warring and equally powerful sides of himself: his idealistic, hopeful self that believes in fairness and justice... and the side that sees hypocrisy and corruption everywhere, the side that sees no point to playing any of the games because the games are all rigged.

That's why I think it's so poignant and heartbreaking whenever he finds himself deadlocked between those two sides. If Harvey let his good side down, he has the potential to become a complete monster. But he cannot allow himself to do that, for whatever reason. Thus we have the coin. It's what keeps the monster in check, and allows him to actually function, even in his own screwed-up way. Without this coping mechanism, Harvey would probably be trapped in deadlock, possibly in a frozen state of inability to choose anything. Imagine the shattered Two-Face from Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, but worse.

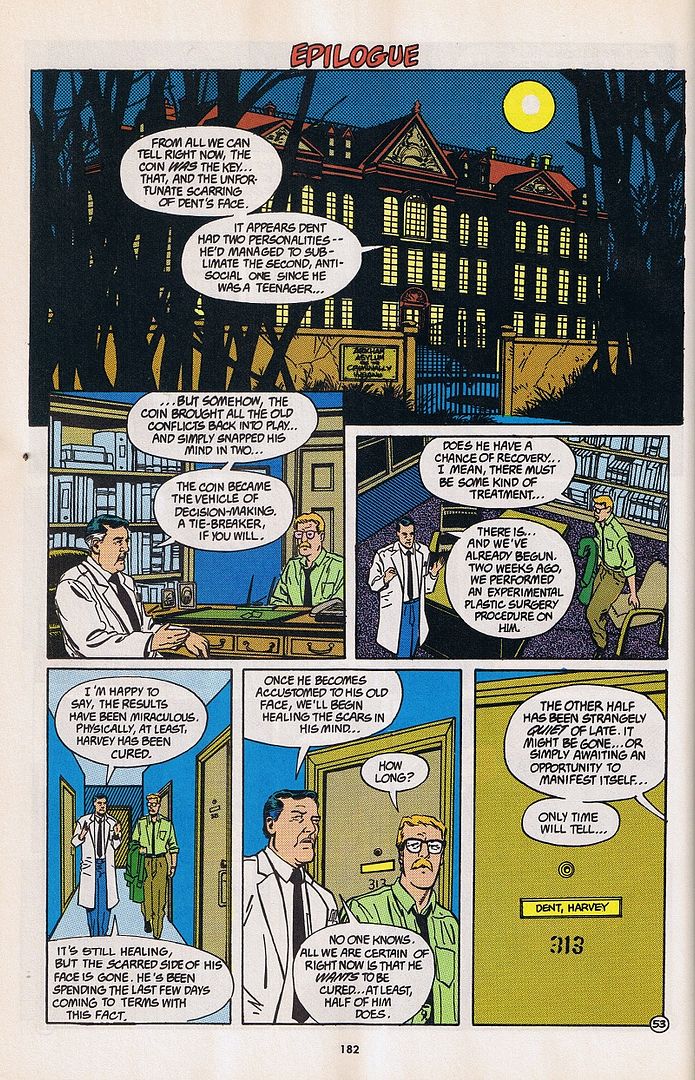

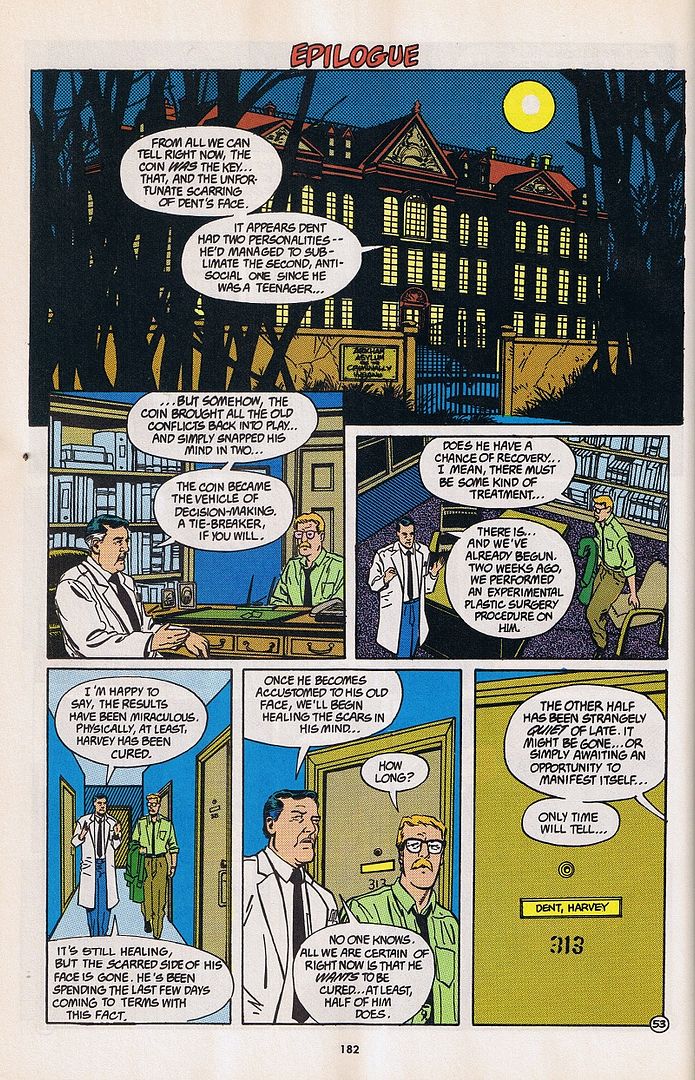

And speaking of Arkham, let us turn to that hallowed institution for EotB's epilogue, where a doctor explains Harvey's mental illness to Jim Gordon in a scene which feels slightly reminiscent of the penultimate scene of Psycho with Dr. Exposition. And just for a second, please join me in pretending that maybe, just maybe, everything is going to be okay for Harvey.

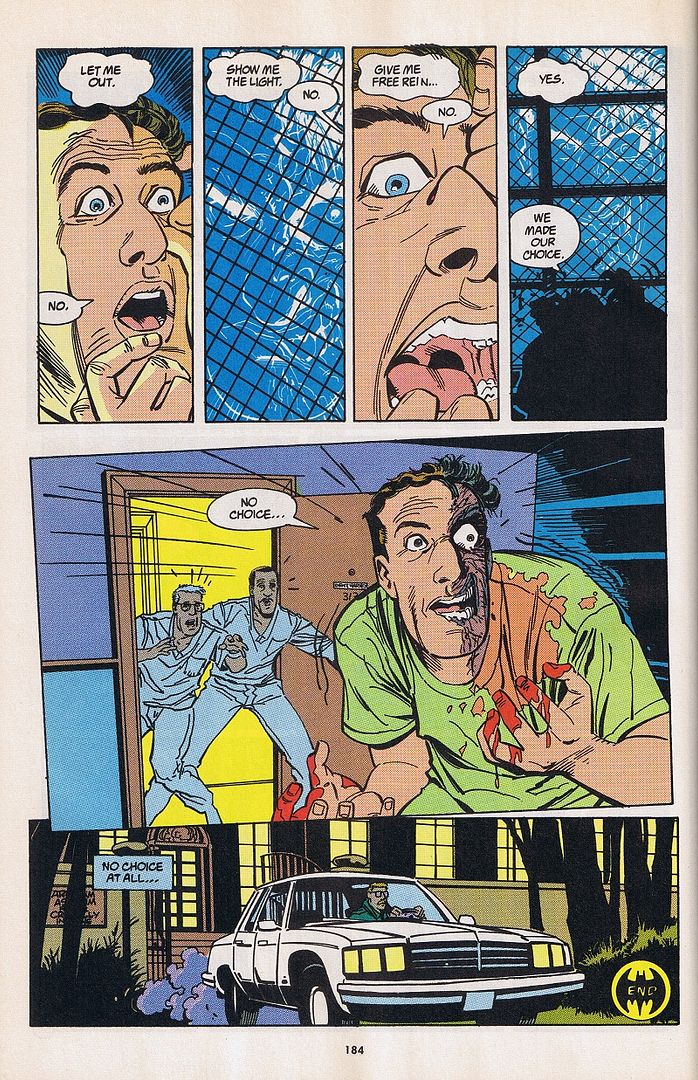

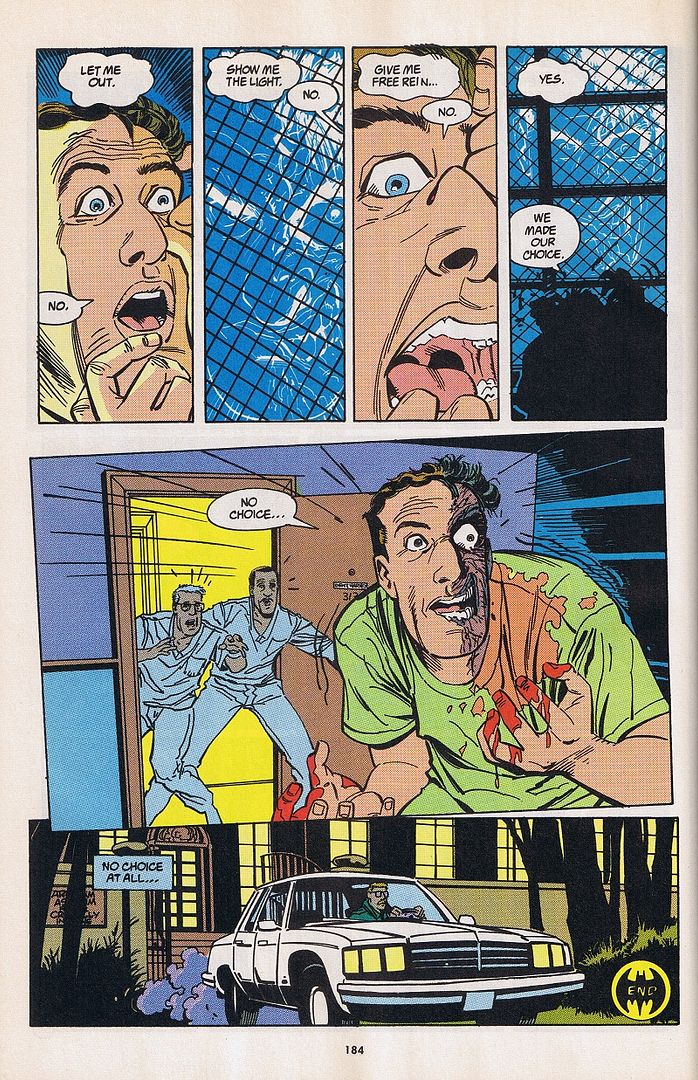

There are few Batman stories that have endings quite so horrifying and sad as this one. Even putting aside the visceral idea of tearing your own face apart with your bare hands, this ending means that Two-Face's scars-the ones we see on the character in his modern-day appearance-are self inflicted rather than the result of acid scarring. This, too, is another idea which was conveniently ignored by subsequent writers, and I can't blame them for that, given how it muddles the basic concept of “good guy gets acid in the face, becomes bad guy.” But that muddling is one big reason why I love this story, and this ending in particular, even considering how much it breaks my heart.

Thus ends the story which I and many others consider to be the greatest Two-Face story ever. Sadly, as I said before, it's long since out of print and, therefore, it remains relatively obscure. What's worse, the same can't be said for other, far more popular stories which either co-opt EotB's ideas (The Long Halloween), ignore them completely ( Robin: Year One), or pervert them in ridiculously awful ways that completely undermine the awfulness of Harvey's abuse ( Batman: Jekyll & Hyde). Whether anyone realizes it or not, this story has a legacy that stretches directly to The Dark Knight, and I live in hope that someday, it'll gain the recognition it deserves for a new generation of readers.

Until then, if you want to read EotB in full for yourself, you'll need to seek out old copies of either Batman Annual #14 or the trade paperback collection, Batman Featuring Two-Face and the Riddler. Copies are available pretty cheap in the usual places like eBay and Amazon.com. Happy hunting, and thanks for reading!

First off, it's an incredibly influential story, although that's mainly because so much of it was directly incorporated into Jeph Loeb's Batman: The Long Halloween, which in turn directly influenced Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight. Despite this, the story remains out of print, and thus unknown to all but the more dedicated fans who make the effort of finding old copies on eBay. As such, I am posting the bulk of the issue here, at least until this issue becomes available in an accessible digital form. Because this is a damn good story, one that deserves to be read one way or another.

More than just a villain origin, EotB is a powerful and tragic psychological thriller, the first story to explore the idea-suggested by the wonderful Grace Dent story in Secret Origins Special that came out mere months earlier-that the seeds of Harvey's insanity were planted long before the acid bath. Other stories have since explored the root of his simmering rage and (depending on the writer) split personality, but not ONE of those stories, not even the truly great ones like J.M. DeMatteis' Two-Face: Crime and Punishment, have recaptured the twisted nuances of how EotB reimagined Harvey Dent.

Right from the start, author Andrew Helfer introduces an original concept to Harvey's origin: the existence of his father, who-in case you couldn't tell-wasn't exactly father of the year material. We don't yet know exactly what he did, but Gilda doesn't mince words: “he's evil.” At this point, you may be assuming that he was abusive, which subsequent stories have included to varying degrees. But that's only half the story (sorry, I'll try to keep the puns to a minimum).

Helfer's other big original concept is that the fateful coin was given to Harvey by his father, rather than it being Boss Maroni's lucky token and the key piece of evidence in the infamous trial where Harvey got scarred. To fans of Two-Face's classic origin, this is a huge and potentially sacrilegious change, but it's not one which Helfer has made arbitrarily. And of course, it's the first of several details which ended up incorporated into The Long Halloween and The Dark Knight.

For now, though, the focus shifts to the plot, which takes place at some point after the events of Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli's Batman: Year One, as evinced by Gordon's rank as Captain and the fact that his still has reddish hair. I was originally going to include this part of the story, but frankly, it takes up entirely too much of the issue and barely features Harvey until near the end. Since this post is review to be long enough anyway, I hope you'll forgive me for skipping through just the most pertinent bits.

Over the previous three weeks, sixteen elderly people have been brutally murdered by a killer dubbed by the press as the “Senior Slasher.” After receiving a report of a disturbance at a nursing home, Batman finally confronts the killer, who happens to be a dignified gentleman by the name of Dr. Rudolph Klemper (“Internist to the stars. Call me Rudy”) who happily confesses to murdering a fresh crop of aged innocents.

“He does that.” Another moment that was used in both TLH and TDK, originated here.

As you can see by the last couple panels there, Klemper's personality changes completely, and he professes both innocence and outrage at his arrest, threatening to sue the city. His performance doesn't fool Gordon, but unfortunately, knowing that Klemper is the killer isn't the same as having hard evidence linking him to the fifteen latest murders.

As thus, the unenviable task falls to D.A. Harvey Dent, who futile struggles for six months of the “protracted court trial” to make the charges stick. Despite his best efforts, however, the evidence is only circumstantial, and to make matters worse, Klemper's performance remains unwavering. After the closing statements are made and everyone awaits a verdict, even Jim Gordon considers taking the law into his own hands.

It's a little startling to see both Batman and Gordon both feeling tempted to commit murder, especially given some of the monsters they'll both be facing (and sparing) throughout their careers. By introducing a killer who is so loathsome, so horrifying, that it drives both men to consider doing the unthinkable, we get to see how even Batman and Gordon are under pressure from the same forces which will eventually help to break Harvey Dent.

I don't know if it was intentional, but I like how the last few panels of Gordon and his family mirrors Harvey and Gilda in their own bed earlier on. To me, this just hammers home the suggestion that Gordon, just like Batman, intimately understands the stress which-unbeknownst to either man-is already weighing on Harvey. While we know that Harvey will himself eventually cross the unforgivable line, the Klemper situation suggests that Batman and Gordon might have done the same themselves under other circumstances.

Heck, the same might be said for much of Gotham City itself, as we see the next day, when the Klemper verdict comes in as not guilty. The courtroom explodes with an angry mob of spectators and family members of victims, furious at both the killer and the D.A. who failed to put him away. In the confusion, Klemper vanishes, and Harvey seeks refuge in the judge's chambers, only to find the monster waiting there for him.

It's interesting that Klemper feels to free to confess in Harvey's presence, given that he felt the same way with Batman. I have to wonder if he saw a bit of himself in Bruce's dual nature as well? Seems like a missed opportunity to draw parallels between Bruce and Harvey to me, but oh well.

Klemper heads back to his lavish mansion, surrounded by the company of friends who call Dent “a buffoon” and offer to help Klemper get back on his feet now that his good name has been sullied. Klemper modestly denies any assistance, assuring them that “I've filed a civil suit for false arrest against the District Attorney's office. Once that's settled, money won't be a problem.” The next phase of his plan is clearly to ruin Harvey and “encourage him to pursue other avenues of employment. I doubt he'll be reelected after we reach a settlement.” It's hard to tell whether Klemper's ultimate goal is to torment or “liberate” Harvey, but we never find out either way.

First off, it's worth noting that this page was originally a longer two-page scene which actually showed just how Harvey orchestrated Klemper's demise. I spoke to artist Chris Sprouse at a convention a couple years ago, and he told me that they changed the scene because the higher-ups at DC didn't think that it was a good idea to show kids a step-by-step instructional guide for how to blow someone up. Here's the original two-page version of the scene:

I have to say, I prefer the elegant simplicity and ambiguty of the edited page. We don't really need to see Harvey's Colombo-villain-esque methods, and Klemper's dialogue feels a bit too melodramatic for this story. If he hadn't exploded, I could almost imagine him twirling his silly little mustache while gloating over “the fool” Dent.

Either way, I must admit, this moment is my single biggest complaint about EotB. Much as I love the story as a whole, I'm personally against the idea that Harvey killed anyone in cold-blooded murder before he became Two-Face, especially this early in the story. The only way this is acceptable is if we understand that this is the first manifestation of his other personality, but considering that the personality conveniently vanishes until much, much later on, it doesn't really hold water. This moment should have been saved for after he became Two-Face, keeping it around as another factor that's slowly eating away at Harvey from the inside.

Fans of The Long Halloween will recognize that four-eyed little weasel as Adrian Fields, who was arbitrarily renamed “Vernon Fields” in TLH, where he was depicted as being more mousy and unassuming. Here, he's instantly depicted as being so smarmy that even Harvey is already mistrustful of him.

And thus we see another innovation of this story: the rooftop pact between Gordon, Dent, and Batman, as the three form an alliance to put Gotham's criminals away for good. It saddens me that most people-including Christopher Nolan and David Goyer!-credits this idea to Jeph Loeb, who famously recreated the scene in The Long Halloween. It's a novel way to reinterpret the Golden Age idea of Batman and Harvey Dent being allies for a modern era where Batman can't be an officially deputized member of the police force. What's more, it formalizes the idea introduced by Frank Miller in Year One of these three men being the sole forces for justice in a corrupt city.

The partnership proves to be incredibly fruitful, with the trio's actions lead to eighty-seven indictments within their first month. Among their triumphs, they succeeded in exposing a towing agency car theft ring, bringing down a violent racketeer and extortionist named “Mad Dog” Pike, and they even managed to secure an arrest for “Gotham's Class-A-One psycho mob kingpin,” Vincent “The Boss” Maroni. For a brief time, everything seems to be coming up roses for law and order in Gotham City.

As someone who generally prefers the idea of Harvey being fervently law-abiding before he became Two-Face, I find it troubling that Harvey had suggested planting evidence at least once before, but I also find it interesting that Batman didn't break off their partnership right then and there. Maybe he just let it go because he knew that he himself operated illegally, and maybe he also forgave Harvey for being under so much pressure. This moment, however, proves to be the breaking point, as we learn when Batman meets up with Jim Gordon at home.

“But he really meant it.” And with that, Harvey has already crossed a line for Batman and Gordon even before he takes a life (as far as they know, anyway). While both Batman and Gordon felt the temptation, Harvey had the intent. Or at least, part of him did. That said, it's strange that it never occurred to either Batman or Gordon to check out Harvey's background before this point, especially given the rampant corruption in Gotham City. A simple check at his medical records could have saved Gotham a lot of bloodshed, and Harvey a lot of anguish.

No matter how many years go by, those panels still give me chills. He just... obliterates himself through the violence. It's especially powerful to see right on the heels of the latest flashback/nightmare we've seen between Harvey and his father. Between that and his fevered rambling about the rage he has been trying to keep down, about how “good” he'd tried to be for so long, we now see that his darker side is no longer manifesting as the cool, controlled, calculating persona that plotted Klemper's death. Now, just like in Batman: The Animated Series, the other part of him is emerging in burst of the form of pure, unthinking rage. Almost like the rage of a child.

The fact that he wants to shield Gilda from himself is poignant, because he's trying to keep himself in check just long enough to protect the only person he loves. It's a shame we don't get to see more of their relationship here, considering how she's traditionally been the only person who can reach Harvey through the madness. Sadly, this isn't a story where Harvey gets to be saved, not even temporarily.

Not only do we learn about Fields' double-dealing (sorry, sorry, I promised no puns), but we also finally get to meet up with this story's version of Vincent “Boss” Maroni right before his big moment. It's a little strange to see that Maroni isn't a bigger deal in this story, that he's presented as less of a nemesis for Harvey and more just a particularly notable suspect to cap off the trio's considerable pile of accomplishments. He's less of a character here and more just a plot device dressed up as a mobster cliché, right down to the tuxedo, which works just fine for this story's purposes. At this point, he's just here to play his part.

Notice that Harvey called Gilda “Grace,” which is the name she'd been given in Secret Origins Special. Putting that odd slip-up aside, this is a moment which-I'm sorry to say-I can't really justify. Why in God's name would she think that it's a good idea to give Harvey, especially a Harvey in this kind of raw emotional state, the coin given to him by his abusive father?

Considering that Harvey had been fiddling with the coin openly over the past seven months since this story began, maybe she thought that he'd now made it his own good luck charm or something? If so, then that's all the more reason we should have seen more of Harvey and Gilda's domestic life. And even then, it's still a pretty shitty good luck charm, unless you consider it good luck that Harvey survived the attack and didn't even go blind.

Also, I think it's rather inspired to have had the coin scarred from the acid rather than by Harvey's own hand. Considering what the coin means to him and how it was used against him, finally, after all these years, the game is fair.

At this point, I'd like to mention that DC produced an official, gloriously awful audio dramatization of this comic, with the adaptation of this scene being a particular highlight. Seriously, give it a listen for yourself and try not to fall out of your chair when you hear that actor's rendition of “NO! WE STAY OUTSIDE!”

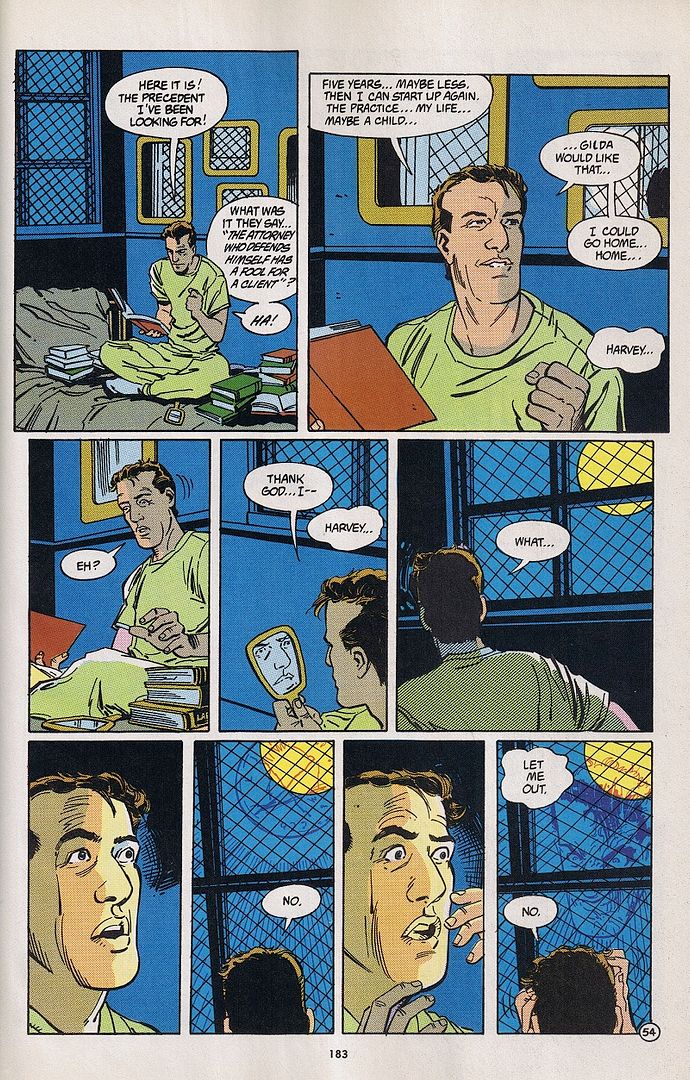

In all seriousness, though, it's worth noting that this is the first story to have Harvey speak of himself as a plural, an idea which I've noticed has been met with some contention. I personally don't mind it for this story, especially since the simultaneous presence of both Harveys is key to the confrontation at the end. But first, Harvey needs to pay a visit to his old assistant, who's already moving up in the world, the little weasel.

With this handy-dandy super-file, we're given a convenient explanation for how a District Attorney somehow managed to reinvent himself as a powerful criminal mastermind. It still doesn't really explain why Harvey would actually want to become a powerful criminal mastermind, but then, most Two-Face depictions suffer from the same lack of motivation.

If I had to guess based on what we see here, I suppose that he's drawn to the criminal life because of the freedom it promises, “a new life... with limitless choices.” Even as he's given up his free will to the dictates of a coin toss, he paradoxically still seeks the freedom of choice. Whether or not any of this makes sense, it'll have to do as motivation until some writer someday comes up with a better reason as to why Harvey made the conscious decision to become everything he ever hated as D.A.

Before you mention it, yes, I know that hebephrenic (AKA disorganized) schizophrenia doesn't really resemble whatever mental illness that Harvey has. It's nice of Helfer to try bringing real-life mental illness into this, but it doesn't really work, unless we somehow accept that his adolescent schizophrenia somehow mutated into his current disorder. Trying to nail down what that disorder is may be impossible, especially given how much of it is tied up in the trauma that Harvey suffered, the exact nature of which is only now starting to be revealed.

He's now so far gone that he just casually killed that guard in cold blood. Honestly, I think that was a bit unnecessary, especially since he didn't even flip for it. He could have just as easily knocked the guard out with the butt of the gun and it wouldn't have changed the story a bit. It's important to know that the good Harvey isn't entirely gone, especially now that both Harveys finally confront the monster who made them.

And here, finally, we learn the true extent of his father's abuse, and how it's turned Harvey into the men he is today. This, right here, is why I'm annoyed by all the other stories and Who's Who and Secret Files profile pages that mention Harvey's abuse without delving into the exact nature of the game itself.

It's not enough that Harvey was physically abused, but his entire psychological state was warped by the game, to the point that he was constantly being torn apart between love and hate. Namely, the love of his father, who he trusted to play fair, and the burning hatred from the part of himself that knew, deep down, that the game was rigged and that his father was just making up excuses to beat him.

Speaking only for myself as the son of an abusive alcoholic, this internal conflict hits very close to home. My father used to play all sorts of mind-games that caused me to doubt my own memory, making me worry that I was overreacting when I tried calling him out on his behavior. I ended up having to shove my anger deep down inside, just on the off-chance that I was in the wrong, even though I knew in my heart of hearts that I wasn't. And yet, a part of me wanted to believe that I was wrong, because I loved my father with all my heart, and I didn't want to think of him as some kind of lying monster.

The only story that comes close to capturing this internal struggle is Two-Face: Crime and Punishment, which abandons the game in favor of the far more commonly-understood abuser logic of Why Did You Make Me Hit You? (Warning: TV Tropes). It's a powerful take on the character, one which turns Harvey's dark side into a destructive force of both twisted self-preservation and self-loathing, but I still prefer the “game” origin because of the significance it gives his every coin toss as Two-Face.

This Two-Face isn't flipping the coin to choose between abstract concepts of "good" and "evil." After all, those ideas are just so subjective and fluid, all to easy to twist and cheapen, as many lesser writers are wont to do. He's caught between two warring and equally powerful sides of himself: his idealistic, hopeful self that believes in fairness and justice... and the side that sees hypocrisy and corruption everywhere, the side that sees no point to playing any of the games because the games are all rigged.

That's why I think it's so poignant and heartbreaking whenever he finds himself deadlocked between those two sides. If Harvey let his good side down, he has the potential to become a complete monster. But he cannot allow himself to do that, for whatever reason. Thus we have the coin. It's what keeps the monster in check, and allows him to actually function, even in his own screwed-up way. Without this coping mechanism, Harvey would probably be trapped in deadlock, possibly in a frozen state of inability to choose anything. Imagine the shattered Two-Face from Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, but worse.

And speaking of Arkham, let us turn to that hallowed institution for EotB's epilogue, where a doctor explains Harvey's mental illness to Jim Gordon in a scene which feels slightly reminiscent of the penultimate scene of Psycho with Dr. Exposition. And just for a second, please join me in pretending that maybe, just maybe, everything is going to be okay for Harvey.

There are few Batman stories that have endings quite so horrifying and sad as this one. Even putting aside the visceral idea of tearing your own face apart with your bare hands, this ending means that Two-Face's scars-the ones we see on the character in his modern-day appearance-are self inflicted rather than the result of acid scarring. This, too, is another idea which was conveniently ignored by subsequent writers, and I can't blame them for that, given how it muddles the basic concept of “good guy gets acid in the face, becomes bad guy.” But that muddling is one big reason why I love this story, and this ending in particular, even considering how much it breaks my heart.

Thus ends the story which I and many others consider to be the greatest Two-Face story ever. Sadly, as I said before, it's long since out of print and, therefore, it remains relatively obscure. What's worse, the same can't be said for other, far more popular stories which either co-opt EotB's ideas (The Long Halloween), ignore them completely ( Robin: Year One), or pervert them in ridiculously awful ways that completely undermine the awfulness of Harvey's abuse ( Batman: Jekyll & Hyde). Whether anyone realizes it or not, this story has a legacy that stretches directly to The Dark Knight, and I live in hope that someday, it'll gain the recognition it deserves for a new generation of readers.

Until then, if you want to read EotB in full for yourself, you'll need to seek out old copies of either Batman Annual #14 or the trade paperback collection, Batman Featuring Two-Face and the Riddler. Copies are available pretty cheap in the usual places like eBay and Amazon.com. Happy hunting, and thanks for reading!