Song of India

photographs and text by Miki Alcalde

The International Community has somehow forgotten that members-only progress can spur a deep sense of injustice. Economic growth of 8% sounds pretty good until you realize it means just an extra $40 for the average Indian. The changes that will improve the life chances of all -ending malnutrition and corruption, reforming infraestructure, education and health care- will take generations to achieve

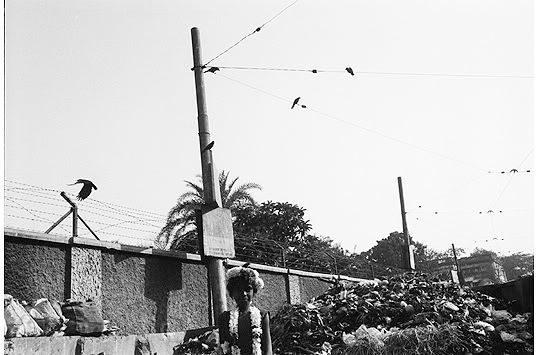

Calcutta

Gandhi was once asked what he thought of Western civilization. "That would be a good idea" he replied. So would an India in which economic development benefited all. Those who see a nation that has already arrived are suffering from a very Indian illusion.

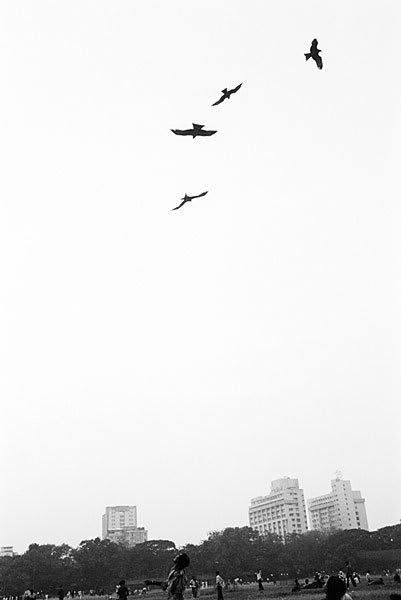

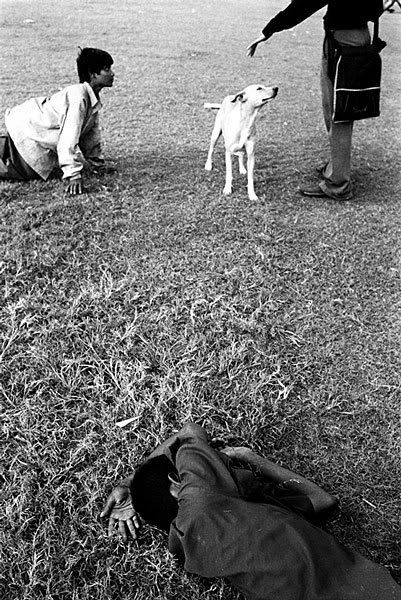

In the evening birds come to the park to be fed by beggars who throw bones with meat to the sky for them to catch. Parks have become the only place for vagrants to try to escape the harsh life they cannot get away from. Many of them have migrated from their villages to the urban centers in search of a better life but have found themselves begging in order to survive.

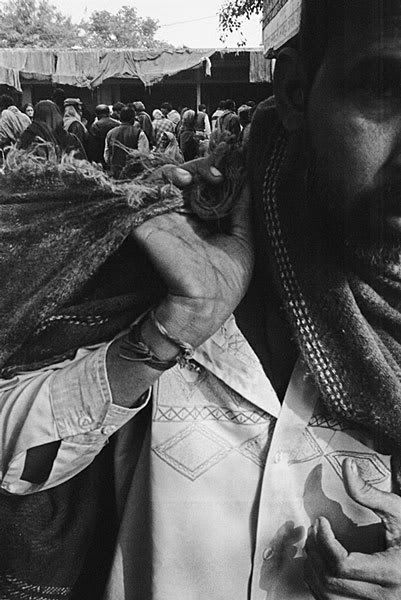

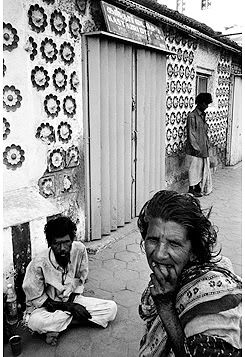

Although the caste system has weakened throughout the years, it still wields considerable power. Caste is the basic social structure of Hindu society. Beneath the four main castes are the Dalits, or Untouchables, who hold menial jobs such as sweepers and latrine cleaners. In this image a Dalit smokes a cigarette while heading to work at the bus station where he cleans the toilets for 55 rupees per day (roughly 1 euro, or $1.25).

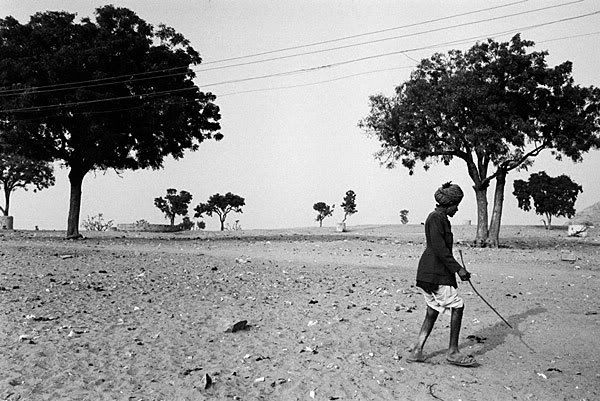

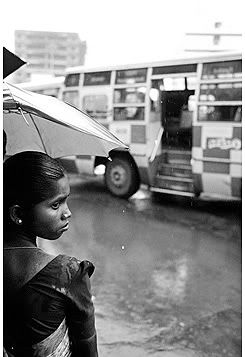

A tribal man awaits the bus to take him back to his village in Jaisalmer's surrounding desert

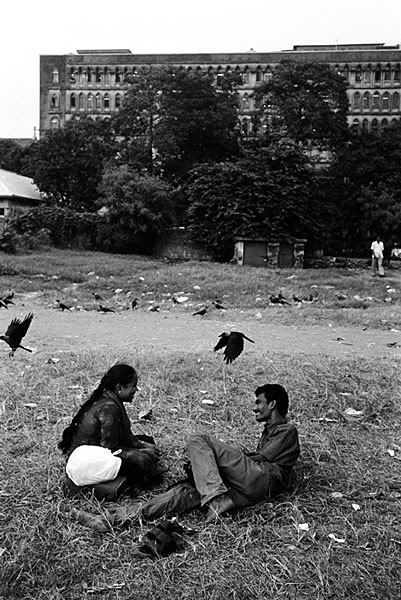

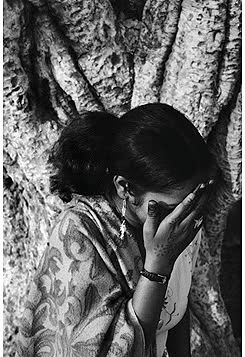

Along with religion, family is at the core of Indian society. Although most Hindu marriages are arranged - it has been traditionally done this way since ancient times - western modernization has introduced popular ways of finding a partner in India: the Internet (through matchmaking Web sites catering to a combined total of roughly 30 million Indians) and the Sunday newspaper. Of the 1,900 matrimonial advertisements appearing in a leading Indian newspaper on just one day in August 2005, only 225 declared caste no barrier. This woman's father does not allow her to have a boyfriend so she has to see him secretly in the park.

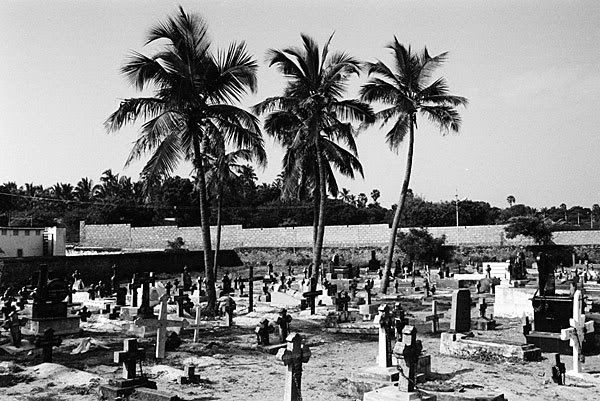

Cemetery in Kanyakumari, where tsunami victims were buried. The Dec. 26, 2004 tsunami, which battered coastal parts of eastern and southern India as well as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, left 10,776 dead and 5,640 still missing. Not long after the tsunami struck, the Indian government came under fire for not only failing to act swiftly enough to assist tsunami victims, but for also initially shunning offers of foreign aid. It later agreed to international assistance. The aftermath showed the profound devastation a natural disaster can cause, but it also showed the dignity with which many survivors faced their blurry future. Many Indian fishing villages were severely damaged but residents managed to remain hopeful.

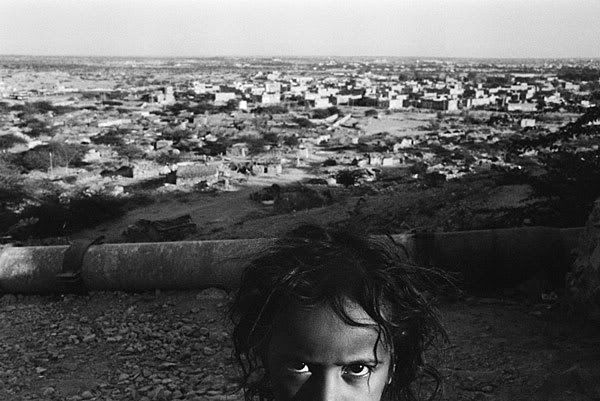

India's tribal communities' future is an uncertain one with the biggest problem being poverty and the erosion of the ancient traditions and culture.

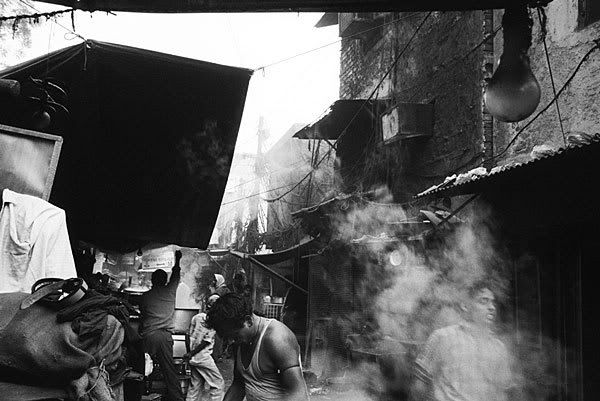

The major causes of poverty in India include illiteracy and a population growth rate that is substantially exceeding India's economic growth rate. Slums are often surrounded by rich neighborhoods and fast-growing western-style shopping malls. To the dwellers of the city's slums, Mumbai's skyline reveals a foreign world they will never be able to reach.

Mumbai's maidans (open grassed areas) are loved by all and are considered to be the lungs of this polluted city. When the government made plans to sell the land to private investors for building apartments, in order to lower the state's debt, many cried out and blamed the never-ending government corruption as the only cause of debt. Without its parks, thousands of people will not have anywhere to go to relax or play the nation's favorite sport, cricket.

Street scene, New Delhi

Work in the urban centers is scarce since immigration from rural India has increased dramatically. For many, hopes disappear as time goes by. Calcutta's bars are men-only territory where locals and immigrants come daily. Fights are common.

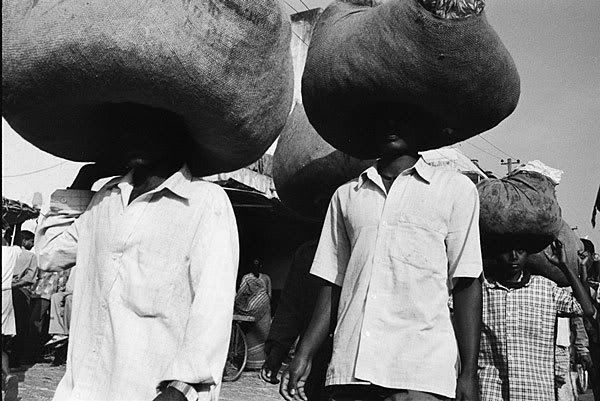

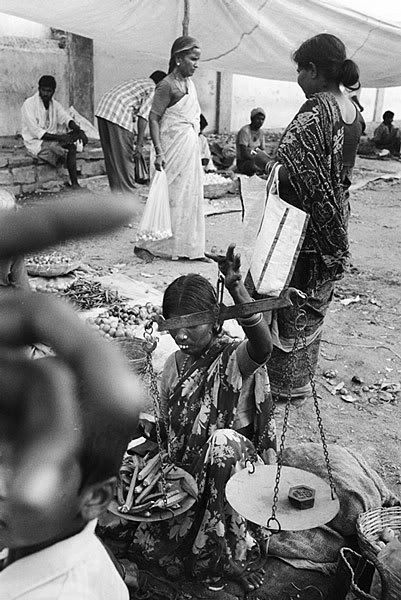

Despite national legislation prohibiting child labor, human-rights groups believe India currently has between 80 and 115 million child laborers - the highest rate in the world. Poorly enforced laws, poverty and lack of a social-security system are cited as major causes of the problem. But in many rural areas laws are never enforced and it is common to see children working in markets and elsewhere.

A boy watches a daily routine in the backstreets of the holy city of Varanasi: the dead being carried by family members to the main cremation centers by the Ganges. According to Hindu religion, dying in Varanasi assures a place in Heaven. Thus, hundreds of thousands are brought from all over India to be cremated here.

Rituals that are believed to have been brought to India by Aryan migrants from Iran who settled in the north about 5,000 years ago are still performed as part of Indian's daily routines or puja, literally offerings or prayers. Those who decide to surrender all material possessions in pursuit of spirituality become holy men, or sadhus, and make pilgrimages to India's sacred places until they die. To westerners, sadhus remain as one of India's symbols of spirituality.

The holy city of Varanasi constantly receives pilgrims from around India. They all come to bathe in the Ganges, "the Mother," according to Hinduism. Every day about 60,000 people go down to the Varanasi Ghats to take a holy dip along a 7 km stretch of the river.

Market scene near Sai Baba's Ashram in Putaparthi

The holy city of Varanasi constantly receives pilgrims from around India. They all come to bath in the Ganges, 'The Mother" according to Hinduism.

The holy city of Varanasi constantly receives pilgrims from around India. They all come to bath in the Ganges, 'The Mother" according to Hinduism. Every day about 60,000 people go down to the Varanasi Ghats to take a holy dip along a 7km stretch of the river.

Street scene, Udaipur

The Ganges river, or Great Mother as it is known to Hindus, provides millions of Indians with an important link to their spirituality

The Dec. 26, 2004 tsunami, which battered coastal parts of eastern and southern India as well as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, left 10,776 dead and 5,640 still missing. Not long after the tsunami struck, the Indian government came under fire for not only failing to act swiftly enough to assist tsunami victims, but for also initially shunning offers of foreign aid. It later agreed to international assistance. The aftermath showed the profound devastation a natural disaster can cause, but it also showed the dignity with which many survivors faced their blurry future. Many Indian fishing villages were severely damaged but residents managed to remain hopeful. A girl stands cheerful in front of her partly destroyed house a year after the tsunami, in the coastal town of Kanyakumari (the southernmost point in India where at least 62 people died from the tsunami.

Market in Jaipur

Jaipur

Pushkar

Raising the living standards of India's poor has been high on the government's agenda since Independence. In a country where roughly one-third of the population subsists on less than US$1 per day, and an estimated 61,000 people are millionaires, it is of no surprise why many impoverished Indians joke about what a great improvement it would be to be reincarnated as a rich man's pet.

During George Bush's recent visit to India, he toured the southern city of Hyderabad to praise an example of everything that's right about the nation. Hyderabad is not only a hub for science and technology, but also an example of what's still wrong with India. In the last few years, thousands of impoverished farmers have committed suicide in the barren, drought-stricken land outside the metropolis.

Arguably the best legacy the English left in India, the railway system keeps the country moving nonstop. There is a whole universe surrounding each station, and people waiting or sleeping in the stations are omnipresent around the clock. Chronic train delays keep Indians wondering how long it will be before India finally takes off. A woman waits for her train after she finds out it has been delayed for another hour.

Cows are one of India's most impressive symbols, venerated throughout the country as holy. Although India presently has one of the world's highest concentrations of poverty, with an estimated 400 million Indians living below the poverty line, thousands of holy cows are fed daily while people starve among them. Feeding both (cows and people) means good karma but somehow cows end up better off. Cows are not only a symbol of a dated tradition to some, but they are also a main source of dirt throughout the country.

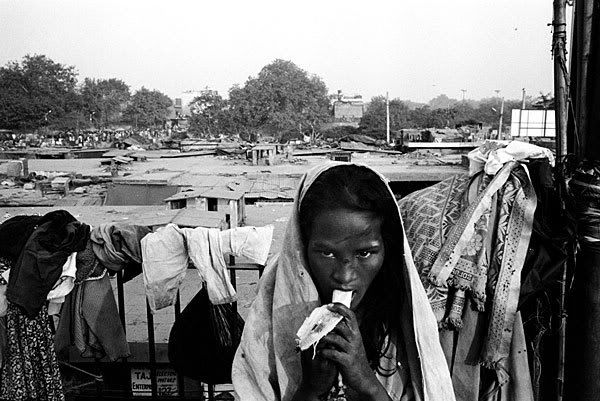

A homeless girl living in the streets of Calcutta

Market scene in Orccha

Gandhi was once asked what he thought of Western civilization. "That would be a good idea" he replied. So would an India in which economic development benefited all. Those who see a nation that has already arrived are suffering from a very Indian illusion.

Beggars gather outside a temple to colect money or food given by devotees

Madurai

Miki Alcalde

Song of India

India is like a jazz song, a meaningless chaos for the outsider, an enchanting world for the connoisseur. Translating feelings into words has been many writers' obsession. Mine is different.

I'm looking at her, but she doesn't know it. She's looking at me, and she thinks I don't know. I'm just two meters away, facing her. I don't want to say anything, I don't want to smile; I can feel everything, and yet it seems as if my mind is somewhere else. I cannot be invisible, I cannot look into her eyes. But I can wait. The feeling I get in this slum area is something that grabs my heart. She is moving around now, talking to her two children, both crying. Behind me people go by; nothing is happening. I cannot leave. And she comes back, where it all started, this time a banana is in her hand; everything is the same, but not quite… this time I have no option, so I raise my camera and take the picture, put down my camera, look behind her; she looks at me, then looks at what's behind her, then looks at me again, as I'm leaving.

The sun sets, and the day is over. Life still explodes in every inch of the country but there is not enough light to photograph, so my day is over. I return to my dingy hotel room, lay down on the bed and think of the long hours spent photographing in the streets that day. I can remember almost everything I felt, that same day, or even a month ago. And every night the same thoughts haunt me: India is out there somewhere, hidden, waiting for me in some fraction of a second. Before I close my eyes, I must hope I've found it that day.

I cannot stop this obsession with images, and the painful feeling of not knowing what will come out of my film for months. But I keep on going, I keep on thinking there is no other way. Time goes by slowly when you try to seize it.

I often think that photographers have to magically organize reality into something meaningful: it's like giving a few basic ingredients to a cook and telling him: surprise me…. In a boring street where nothing is apparently happening, you have to sort it out to create a picture that makes the viewer feel something. To me, photography is all about feeling, about creating images that tell you something, that make you feel something.

I have heard that India is booming, but I don't seem to find this change. I know it's somewhere, I know it's real, I don't want to question it. I just want to walk and see, to travel the country and look at everything. From the train I see life as it must have been hundreds of years ago. The cities may be changing, but India is rural. So the change must be affecting just a few.

The sun rises. I get up and grab my Leica, and it all begins again. After one or two hours of walking, I manage to escape the city center and find myself looking at the sea. I'm in Mumbai, but it's quiet, I can't hear the traffic. Far away, on the horizon, buildings rise; it seems to be somewhere else, maybe another country, or planet. But it's India, still… as I compose to take a picture, two silhouettes walk by, encompassed in rhythm and shape. As I press the shutter over and over again I feel I am witnessing something I cannot yet comprehend. It is that night when I finally understand what unfolded before my eyes: far away, on the horizon, so far that it's even hard to see, is the India that most Indians will never be able to reach. They are not even persons, just silhouettes on the country's so-called boom.

After one month and a half, I finally reach India's southernmost town, and the aftermath of the Tsunami is still felt, especially on the fishing communities that lie right on the shore. It's sunny and very hot. The majority of the houses have been rebuilt but there are still ruins and destroyed wooden boats. I head to the cemetery where I'm confronted by three palm trees surrounded by dozens of crosses. Putting my feelings into words is what I would do if I were a writer. But I prefer to look at the picture again; I want to remember the sound of the sea at that particular moment, the heat, the strange look of that cemetery, my confusion….

As I head back to the fishing village I can see the effects of the Tsunami again in many of the houses. I notice more ruins than before. Suddenly I see a young girl on her way to school, or so it seems. I manage to turn back and frame very quickly, just in time, when a crow flys by. I take a picture, the girl standing proudly on top of her destroyed house, with a subtle smile, as if nothing had happened.

It is hard to leave India, although for many, it is hard to make the decision to arrive. Or you may even leave it after months in the country and find yourself missing it a few days later. It is a love/hate relationship. You are in Mumbai surrounded by cars, pollution, heat, noise. It is very hard. But you are there and it's all that matters. Being in India is important; there is no other place like it on earth, so yes, you hate it, but 10 minutes later you love it again, and so on. And when I cannot take it any more, I remind myself: "This is India, and I'm here." If I had to choose a word to describe the country, it would have to be 'intense.' It is hard to imagine that a place can hold so much intensity; it doesn't matter where you look, it's full of life everywhere.

In Calcutta I am told about the local spirit, and the bars that are filled with men getting drunk with it from 4 p.m. onwards. I decide to visit one of them, but as soon as I enter I am shocked. It is not what I expected; I am not welcome here, but I feel unable to leave. I quickly head upstairs like I know my way and start taking pictures as if it was just a regular bar, not completely knowing what I'm doing. As soon as I start, about 40 people stare at me and start shouting. I think I'm lost, but luckily I see a hand waving at me, inviting me to sit down. They're all drunk and seem very violent. They don't talk, but shout at one another and at me. I managed to stay calm and take a few pictures, hoping I never have to go back to that place again. After a while someone says, "it's better if you leave now." And so I leave.

On the park, on a different day, I am lucky enough to capture a moment that is one of my favorite pictures that I took in India. A homeless boy, in a dog-like posture, sees how a man plays with a white dog, and I feel the boy wishes to be the dog. The feeling I get when I see that is just what I find at the bottom of the frame: an abandoned human being, lonely and helpless, forced to continue living, no more.

So to me India is like a jazz song. Not any jazz song, but my favorite jazz song. I save it like a precious treasure. I don't want to have enough of it. I want to always love it, I need to always be able to count on it... because I will be in need of it again, sooner or later...

Born in 1979 in Spain, photographer Miki Alcalde studied marketing in Madrid and Florida, graduating with an MBA in International Marketing by Eastern Michigan University in 2002. He joined Magnum Photos in New York for a one-year internship in June 2002, and has been travelling and photographing ever since. He has recently returned from three months in Africa and the African Peninsula (Egypt, Sudan, EtiopiAa and Yemen).