William Klein: From Painting to Photography, Fashion to Film. Part 2.

Mode en France. History of Fashion

France, 1984

режиссер: William Klein

композитор: Serge Gainsbourg

в ролях: Azzedine Alaia, Agnes B, Bambou, Dorothee Bis, Jean-Paul Gaultie, Arielle Dombasle, Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, Christian Lacroix, Karl Lagerfeld

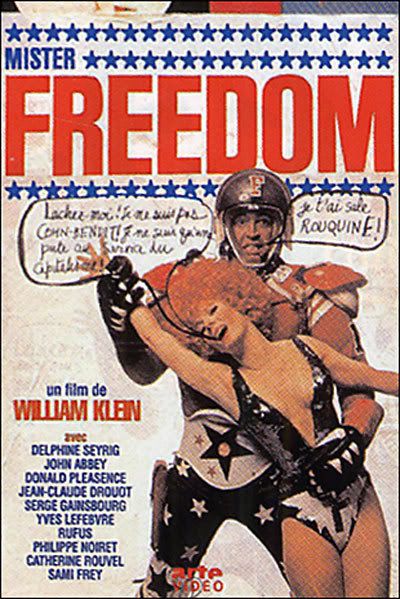

Mr. Freedom

France, 1969

режиссер: William Klein

в ролях: Delphine Seyrig, John Abbey, Donald Pleasence, Jean-Claude Drouot , Serge Gainsbourg, Yves Lefebvre , Philippe Noiret, Sami Frey, Yves Montand, Simone Signoret

He is famous in the artworld for his revolutionary photographs and films, but he is also renowned in the fashion world for his breakthrough fashion photographs. How does he reconcile the two? As he explains to art critic Sophie Berrebi, the artistic and the commercial are more closely intertwined than one might expect.

Sophie Berrebi: One of the most striking things about the fashion photographs you took for Vogue is the proliferation of artistic references within them. I imagine this had to do with your background as a visual artist?

William Klein: I was basically a painter. I had come to Paris to paint, in 1948, and for several weeks I studied at Fernand Leger's studio. For me it was a revelation to meet someone like Leger, who changed our take on the artworld - who said galleries and museums were bullshit, and who could talk about Russia, talk about America. But at the same time I had come to Paris to soak up the city I had dreamt of. I wanted to go to La Coupole and run into Picasso, Giacometti and even Hemingway! But Paris after the war was convalescent. Nothing much was happening. The star artist in Paris was Bernard Buffet, if you can imagine.

Weren't you more interested in abstract art?

There were three American hopefuls - Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman and myself - and we were all friends, and looking for answers. I turned to the Bauhaus, the Russian constructivists, and the de Stijl group. I was attracted to them because of the multi-disciplinary aspect of their work; I thought that was the future. So, even though I was living in Paris I was tuned into the Bauhaus of 25 years before.

How did you get involved with Vogue? What kind of contract did you have?

The art editor from Vogue, Alexander Liberman - a legendary character in publishing - had seen an exhibition I had done of abstract photographs, and he got in touch with me when he came to Paris for a collection. He said 'Why don't you work for us?' I said 'Doing what?' I hardly knew what Vogue was about. I showed him stuff I was doing: graphic work, reproductions of my paintings, etc. He asked me if I had a project in mind, and I said, yes, I'd like to do a photographic diary of my return to New York. He said, 'Okay, we'll do a portfolio' (which, of course, they never did). But he gave me carte blanche, and financed the whole thing. So I did the photos for the book on New York [Life is Good and Good for you in New York (1956)] and at the same time, some portraits and still-lives for Vogue. Liberman gave me a contract, which was incredible at that time. I mean, I couldn't see what I could possibly offer to a fashion magazine.

How did working for Vogue affect the technical aspects of your work, by comparison with the violent, grainy photos in your New York book?

At first, I was intimidated by the technique of fashion photographers. Everything was so sharp and clean. But soon I realized that, outside of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, there wasn't much of great interest. My photos for the New York book were 'fotografia povera'! Those pictures were in a sense 'politically incorrect'. The prevailing ethos of photography came from Cartier-Bresson, who said, 'You don't ever reframe a photograph. Photography is a Zen thing. You aim the arrow and shoot'. That was his message. I didn't see why you couldn't reframe and manipulate in the dark room, especially if you had minimum equipment, and I didn't have any equipment. I had one camera and two lenses - and if I was far away, since I had no telescopic lens, I would take a picture and think, 'I'll do it in the darkroom'.

A picture like the one of Barbara Mullen - Hat with Five Roses - is actually a detail. I only had a Rolleiflex and I couldn't get that close to her. What you can't see is that there's a lot of space all around, her bony elbows, her gloves, a bandana around her breasts.

How did you relate to other photographers at the time? I heard you were hired to counteract the success of Avedon at Harper's Bazaar.

In those times the media were far more limited than they are today, and the collections attracted a lot of attention. The publication of the issues of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar in September and March on the French collections were awaited with bated breath by the women, by the stores, by everybody. Avedon would come and do a whole story - like a movie on the collections - and the magazine, Harpers Bazaar, would really swing. Penn would do these very beautiful photographs for the Vogue collections, on white backgrounds, but rather staid. Liberman had this thing about me; he thought I could jazz up the magazine. So I was asked to do the collections a very short time after my first contact with Vogue, and it was supposed to be an answer to Harper's Bazaar.

Yet your whole attitude towards fashion was very different from that of Avedon or Penn.

I was an outsider to fashion photography, to say the least. For instance, I found the fashion shows a drag, and I never went to them. I was only interested in photographic ideas. The editors would bring in the clothes and I would find a way to photograph them. But Avedon would help choose the dresses because he loved fashion, whereas for me the photographs were always parodies on fashion. Actually, as long as I showed the clothes, the magazine didn't care what I did. The editors wanted the women who turn the pages to stop and look.

The cover image from In and Out of Fashion was done at that time, and it was censored. I had to do photographs of fancy hats, and I thought, 'Let's have the model smoke a cigarette like a sailor'. Remember that when a woman in a fashion photograph at that time was pictured smoking, she would have gloves, she would have a cigarette holder, looking very snooty - and here she was, looking like she'd just picked up a butt from the street! Years later, at the time that my film Who are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966) was released, I did the first cover with the black model from the film for French Vogue, where Edmonde Charle-Roux was the editor, and it was censored, and she was fired from Vogue. It's hard to believe now but very many of my photographs were censored.

The models you used often looked like they were really acting in your images - and you even turned one of them, Dorothy MacGowan, into an actress when you made Polly Maggoo.

Barbara Mullen, who is featured in the eyestorm portfolio, was the first model I really related to, because she was a clown; she was able to laugh at the scene. You can't recognize her from one photo to another. She wasn't really beautiful, but she moved and wore makeup in such a graphic way that she had something else. What I also liked about her was that she was a tough New York girl from the streets. She was one of the four or five models of the day, along with Dovima, Jean Patchett, Evelyn Tripp - but the public never knew their names like they do the stars of today.

Dorothy MacGowan, who I used a lot, was also a kid from the streets; she came from Brooklyn, from a Catholic-Irish family, one brother a cop, the other a priest. I saw her as a sort of Alice in Wonderland character. That's what I thought when I wrote the scenario for Who are You, Polly Maggoo?, which was the end of my relationship with Vogue. I wasn't fired over the film; that would have been too obvious even though I sent up the editor-in-chief, Diana Vreeland, whom everybody revered at the time as The grande dame of fashion. I was fired because I was working on the film Far From Vietnam, condemning the American intervention.

Many of your fashion photographs seem to have a great cinematic quality about them. Were you thinking about making movies when you shot fashion for Vogue?

Yes. I thought it was a way of training to do movies, working with models and extras, getting used to working fast, under pressure, with lights, decors and big crews. For me, anyhow, it was all part of a Theater of the Absurd.

Sophie Berrebi is a Paris-based art critic.

Уильям Кляйн: скетчи на моду.

…В модную фотографию, в царство стиля, пошатывающегося на длинных шпильках и манерно опускающего ресницы, Кляйн вошел через черный вход. В редакцию Vogue - с нью-йоркских авеню и стрит, переполненных «решающими моментами» и превратившимися в урбанистический джанк ошметками культуры. Кляйн был художником и скульптором, жившим в Париже. Там он случайно знакомится с директором американского Vogue и получает в 1956 году приглашение в Нью-Йорк. Кляйн снимает жизнь улиц, фиксирует реальность в духе Картье-Брессона. Впрочем, если Брессон всегда стремился остаться невидимым, то Кляйн, напротив, часто заговаривал с людьми, чтобы видеть их реакцию. Контрастные черно-белые снимки американским издателям и журналам кажутся вульгарными, агрессивными, непрофессиональными. Зато восхищают французов. Вышедшая в Париже книга о Нью-Йорке становится революцией в деле фотографии - как поп-арт в искусстве. В оформлении книги Кляйн берет на вооружение кричащую типографическую безвкусицу дешевых рекламных проспектов и таблоидной прессы. И получает Приз Надара. Делает книги о Риме (1960), Москве (1964) и Токио (1964). С таким опытом, без представлений о павильонной съемке, он оказывается теперь творцом имиджа и диктатором стиля, но все с тем же взглядом уличного фотографа, которого интересует совсем не расположение теней и света на манекенщицах и их платьях. Он ищет взгляды, наблюдает за движениями тел, глаз, складок на тканях, юбок на коленях, за минами тщеславия. Он, теперь вхожий во все двери без пропуска, пользуется моментом и иронизирует над модой и медиа. Между тем, прогульщик редакционных летучек журнала Vogue, Кляйн, сам того не заметив, изобрел фотографию моды в том виде, в каком мы ее знаем. Его идеи до сих пор пережевываются современными фотографами. Он помещает своих моделей в ряду манекенов, выталкивает девушек на улицу, в автомобильный хаос, в толпу, лица которой на готовой фотографии превращаются в белые маски.

Вот он инсценирует спектакль под названием «Смерть парижской моды». Заигрывание со смертью и сегодня эпатаж для многих модных фотографов…

А фильм об одной из коллекций Готье начала 80-ых… Кляйн одевает уличных продавцов в hautе couture и снимает их за работой на видео. Попавший в кадр Готье, поправляя манжеты модели, произносит сакраментальную фразу: «Ты можешь быть совершенно нелепо одет, но если при этом ты в себе уверен, то все будут нормально реагировать». Собственно говоря, вот он, источник вдохновения Кляйна - столкновение жизни, с ее бытовой бестолковостью, и моды, стремящейся к совершенству. Оказываясь вместе в кадре, жизнь и мода выглядят неуклюжими и ранимыми. Здесь и кроется обаяние его фотографий и фильмов. Как Вуди Аллен, он везде ищет повод сострить, но без цинизма; в собственных гэгах не пытается скрыть завороженность тем, над чем сам смеется.

Его поздние работы в фото и видео для модного бизнеса - чистая деконструкция стратегий последнего. В автобиографическом фильме «In & Out of Fashion» Кляйн вспо-минает эти съемки: модели в белом узком каменном мешке, картинно, в нелепых позах, с видимыми напряжением корчатся в шелковых платьях и рассказывают истории о трудном детстве, кривых зубах (старая сказка о гадком утенке), о любовных неудачах. Манерные фразы о нелегком пути наверх, о хлебе, добываемом буквально потом и кровью, - не более чем еще один созданный внутри модного бизнеса миф. Отрицание существования какой-либо правды о моде и ее создателях и возможности ее вообще найти - любимая тема Кляйна. Из нее он сделал сказку «Кто вы, Полли Магу?» (1966), свой первый художественный фильм. …В кино, кстати, он тоже совершил несколько бархатных, к сожалению, прошедших незамеченными, революций.

Провокации на кинопленке

Кинокамеру Кляйн берет в руки на первом показе Ив-Сен Лорана: документирует хаос за кулисами. Черно-белые, почти неряшливые кадры, нейтральность интонации - это ему показалось недостаточным. Позже он снимает свою гениальную сатиру на модный бизнес, первые кадры которой - показ мод начинающего модельера. Ингредиентами этого коктейля, пародирующего стилистику «новой волны» стали американская модель, любимица парижского Vogue Полли Магу, Принц из Далеких Северных Стран Игорь Бо-родин, влюбленный в ее рекламную фотографию, пара шпионов, посланных отыскать будущую принцессу, редакция журнала Vogue, режиссер телепередачи «Кто вы, Полли Ма-гу?». Кляйн мешает жанры, стили, пародирует их, становится вдруг серьезным или острит с серьезной миной. Его фильм не поддается никакой классификации и сравнениям. Современники автора восприняли этот шедевр с недоумением.

К сожалению, история распорядилась так, что мир знает лишь фотографа Уильяма Кляйна, а не режиссера. Его фильмы оказались умнее самих себя. Темы и приемы, в тот момент находившиеся на периферии внимания, переместились в центр десятилетия спустя. Вильям Кляйн вполне мог бы быть звездой 90-ых со своими 30-летней давности фильмами. Кинокритики, облизываясь от наслаждения, читали бы их как постмодернистские тексты о мифах современной культуры, напичканные иронией, цитатами и аллюзиями. Но даты убедительно говорят, что мы, пожалуй, имеем дело с оригиналами, которые знаем лишь по виденным у других режиссеров цитатам.

…Впрочем, всю эту путаницу со смыслами, вкладываемыми в произведение искусства его автором и его зрителем, иллюстрирует история со снимком, сделанным в Москве в конце 50-ых: выхваченные из толпы лица - старуха в платке, рабочий с высокими скулами, пацан с сигаретой… Кляйн вспоминает, что современный философ Ролан Барт увидел в нем прекрасный этнографический материал: «По ней можно судить, как выглядели и одевались русские в то время». «Конечно, каждый волен присваивать фотографии какие угодно смыслы, особенно Ролан Барт. Но для меня в этом снимке куда больше смыслов, чем просто этнографического интереса. Но каких, не скажу». Вот он, весь Кляйн: оставленных им смыслов нам еще хватит расшифровывать лет на 20.