Wuthering Heights, by Emily Brontë

One-line summary: Broody McBrooderson starring in Emily Brontë's pioneering work of dysfunctional obsessive lovers may shed some light on why so many chicks dig Snape.

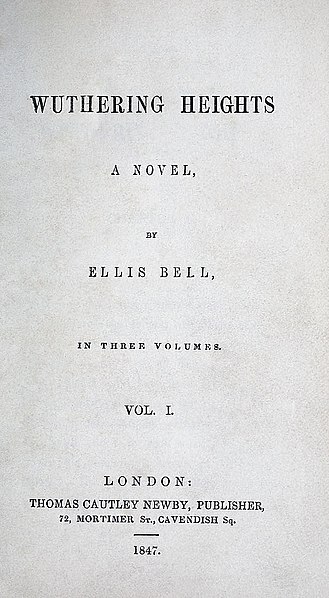

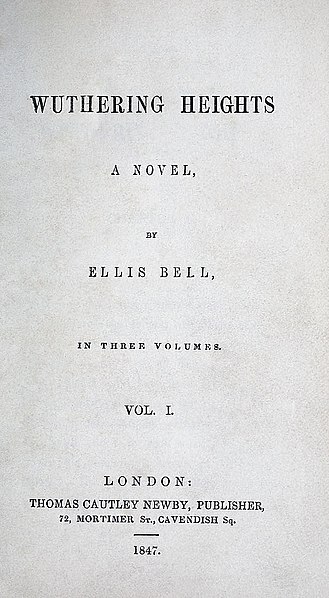

Originally published 1847, approx. 116,570 words. Available for free at Project Gutenberg.

Wuthering Heights", Emily Brontë's only novel, is one of the pinnacles of 19th-century English literature. It's the story of Heathcliff, an orphan who falls in love with a girl above his class, loses her, and devotes the rest of his life to wreaking revenge on her family.

Crossposted to books1001 and bookish.

Wuthering Heights is one of those classics I'd never read, nor had I ever seen any of the movies, so all I really knew about this story was that it's a Victorian romance with a guy named Heathcliff whom people generally consider to be an asshole and who's the archetype of the modern "bad boy" romantic hero.

Apparently, this much-beloved book is considered by many to be a timeless romance. Anyone who thinks Wuthering Heights is a romance must suffer from the same brain damage that makes Edward Cullen dreamy and Severus Snape sexy. This is not a love story; it's a hate story. Everything that happens is motivated by hate: mostly Heathcliff's, but Heathcliff is like a black hole of hate who sucks everyone else into the orbit of his own hatred and makes them hateful, too; in the end, everyone spirals to their doom. For all of his speeches about how Cathy is his soul, Cathy's "I am Heathcliff" speech comes closer to the truth: the two of them don't so much love one another as feel such a desperate sense of possession for one another that their mutual obsession occludes all other feelings.

This is not a love story

The book begins when Mr. Earnshaw, master of Wuthering Heights, a gloomy estate on the Yorkshire moors, brings back an unexpected "present" from a trip to Liverpool: a "gypsy" orphan in his arms. He found it (yes, everyone refers to the boy as "it") on the streets, apparently parentless and starving, and brought the boy home.

‘And at the end of it to be flighted to death!’ he said, opening his great-coat, which he held bundled up in his arms. ‘See here, wife! I was never so beaten with anything in my life: but you must e’en take it as a gift of God; though it’s as dark almost as if it came from the devil.’

We crowded round, and over Miss Cathy’s head I had a peep at a dirty, ragged, black-haired child; big enough both to walk and talk: indeed, its face looked older than Catherine’s; yet when it was set on its feet, it only stared round, and repeated over and over again some gibberish that nobody could understand. I was frightened, and Mrs. Earnshaw was ready to fling it out of doors: she did fly up, asking how he could fashion to bring that gipsy brat into the house, when they had their own bairns to feed and fend for? What he meant to do with it, and whether he were mad? The master tried to explain the matter; but he was really half dead with fatigue, and all that I could make out, amongst her scolding, was a tale of his seeing it starving, and houseless, and as good as dumb, in the streets of Liverpool, where he picked it up and inquired for its owner. Not a soul knew to whom it belonged, he said; and his money and time being both limited, he thought it better to take it home with him at once, than run into vain expenses there: because he was determined he would not leave it as he found it. Well, the conclusion was, that my mistress grumbled herself calm; and Mr. Earnshaw told me to wash it, and give it clean things, and let it sleep with the children.

Mr. Earnshaw's daughter Cathy is fascinated by the orphan (whom they name Heathcliff), and they become lifelong friends. Cathy's brother Hindley is less enamored; he's immediately filled with jealousy and contempt. The obsessive love between Heathcliff and Cathy, and the grudge between Heathcliff and Hindley, who sees the orphan as supplanting his rightful place, fuels the rest of the story.

Heathcliff is often called a "gypsy." While of course you can take it for granted that Victorians were racist as all hell, one wonders whether most Victorians were unable to imagine non-gentry as anything other than an indistinguishable melting pot of dark-skinned people who all spoke gibberish, or if this was Emily Brontë's ignorance.

‘“What culpable carelessness in her brother!” exclaimed Mr. Linton, turning from me to Catherine. “I’ve understood from Shielders”’ (that was the curate, sir) ‘“that he lets her grow up in absolute heathenism. But who is this? Where did she pick up this companion? Oho! I declare he is that strange acquisition my late neighbour made, in his journey to Liverpool-a little Lascar, or an American or Spanish castaway.”

Supposedly, Edgar Linton figures it's equally likely that he's a gypsy, an American, a Spaniard, or a Lascar. As in many other interactions, there were parts of this book that didn't ring quite true to me, but it was hard to tell whether this was really the manner of thinking and acting at the time, or Brontë's fancy, as she had to imagine much of what the outside world was really like.

I bring this up not to bash Brontë for her racism (she was a sheltered vicar's daughter and probably never met another person outside her class) but because I just find it kind of interesting to trace the evolution of racial attitudes over time. Something a lot of modern readers may not be aware of is that in Victorian times, it wasn't just a different skin color or nationality that made you a different race; Victorians believed that the different social classes were practically different species as well. (This justified treating the lower classes like animals; they were thought to literally not feel or suffer the way the upper classes did, an attitude Charles Dickens addressed directly in his novels, which were much more critical of his own society.)

Likewise, modern readers tend to assume that anything described in an old classic is an authentic representation of the attitudes and people of that era, which may not always be so. Suppose someone two hundred years from now reads Twilight and assumes that Stephanie Meyer was actually describing how teenagers acted in the early 21st century?

Isn't it Byronic?

It's not Heathcliff's dubious lineage that makes him the despised cast-off of the Earnshaw household, but the fact that he is not a "gentleman"; his failure to be "raised" to Cathy's level, and his degradation compared to his step-brother Hindley, who went off to school. Of course, his situation is not helped by the fact that he's just naturally an asshole.

After reading the book (and then watching a bunch of film adaptations -- see below) I think the first point to observe is that Emily Brontë's Heathcliff is not at all romantic, and I don't think Brontë intended him to be. He doesn't once say a kind word to anyone throughout the book -- not to Mr. Earnshaw, the man who took him in and treated him like a son; not to Nelly, the nurse who takes care of him and Cathy and even enables his continued relationship with Cathy after she marries Edgar Linton; and not even to Cathy.

The most affectionate thing he ever says to her is that he'll refrain from doing violence on her say-so. Heathliff is an almost demonic creature who spends most of the book wreaking destruction and vengeance against anyone who's ever slighted him. ("Slighting" him includes being related to anyone he dislikes.) If not for the fact that he seems to love Cathy (albeit obsessively and spitefully, with that kind of hateful love that only severely damaged personalities can exhibit), he'd unquestionably be considered a sociopath.

It's true that Hindley starts treating Heathcliff like shit the moment his father dies, unleashing years of pent-up resentment and going out of his way to humiliate him. But it's hard to feel sorry for Heathcliff when even before that, he never showed the slightest gratitude or affection for anyone but Cathy. And when he returns to Wuthering Heights after his three years abroad, he's gone from sullen savage to psychopath. He destroys Hindley, deliberately raises Hareton as a brute, humiliates Edgar Linton, rapes and beats Isabella, and torments Cathy. After Cathy dies, he goes on bullying and abusing children for the crime of being alive, just to make their (dead) parents suffer.

Interestingly, considering Cathy dies only halfway through the book, a lot of people seem to think that Wuthering Heights is all about the relationship between Heathcliff and Cathy. There is an entire second act involving Cathy's daughter Catherine, Heathcliff's son Linton, and Hindley's son Hareton, in which Heathcliff's vengeance, obsession, and hatred comes full circle.

As with so many of these desperate, dark Victorian novels, much of the plot is driven by outright gratuitous cruelty; so many of the disasters that befall everyone could be avoided if just once, someone decided not to be loathsome.

The Unreliable Narrator and Reading Between the Lines

Something one would miss from experiencing Wuthering Heights only through the movie adaptations is that it's written in several layers. The ostensible narrator of the book is Mr. Lockwood, a tenant of Heathcliff's who comes along at the end of the story to rent Thrushcross Grange, and thus hears the story second-hand. He hears the story from Ellen Dean (Nelly), the housekeeper who served both the Earnshaws and the Lintons, who thus becomes the first-person narrator of many of the chapters. There are also chapters "narrated" by other characters, through Nelly, who is supposedly repeating letters she's received and conversations she's had word-for-word, a common literary device at the time.

What makes Nelly interesting is that she frequently makes asides about how she failed to do this or that, regretted something she said or didn't say, or realizes something was a mistake in hindsight -- but always absolves herself. If you pay close attention, you realize that Nelly was a bit of a gossip and a sneak, always looking for opportunities to tattle and stir up trouble, convinced that she was acting in the best interests of Cathy or Catherine. When you realize that by her own admission, she frequently acts out of cowardice, and sometimes acts out of pique, you begin to question how accurate her portrayal of the other characters may be. Clearly she doesn't like her fellow servant Joseph, so is he really the obstreperous Bible-thumping old coot he seems to be, or was Nelly perhaps embellishing the unpleasantness of his personality a bit? And could she likewise be villainizing Heathcliff unjustly?

Even Lockwood, who is only really "present" at the beginning and the end of the novel, in the bits he narrates shows signs of putting his own bias into the tale (such as his assessment of Catherine, whom he describes as a petty, spiteful brat when she fails to be impressed by him -- never mind that she's basically a prisoner in a household where everyone hates her -- and only gives a more pleasant description of her later).

This does give a bit more justification for the wildly varying interpretations the book has been given in film adaptations. And being a Victorian novel where there's a lot that couldn't be made explicit, critics have a great time coming up with "fanon" speculation. Did Heathcliff actually kill Hindley? Was Catherine actually Heathcliff's daughter? Several film versions make it pretty explicit that Heathcliff and Cathy were lovers, but in the book, there is no evidence that they really went that far, unless one reads liberally between the lines.

Emily Brontë the Author

Wuthering Heights got mixed reviews when it was published; some critics called it "immoral" and "pagan." Unlike her sisters Charlotte and Anne, Emily only ever wrote one novel. She was working on a second when she died the year after Wuthering Heights was published.

Wuthering Heights is full of death. Just about everyone dies young, in childbirth, or of drink and despair. Almost nobody gets a happy ending. Since this was pretty much how Emily and her entire family lived and died, it's not surprising that Wuthering Heights is a fantastically gloomy novel, both morbid and full of repressed fantasy, showing the same sort of imagination that the Brontës first conceived in their fantasy world of Gondal.

To be honest, I didn't much like Wuthering Heights as a story. If Emily Brontë had written other novels, I wouldn't be putting them on my TBR list. But I do think she was a genius, and you can see it in her writing, in the wild imagination and the subtext of her book, despite being written from what was essentially a fairly limited worldview.

Emily Brontë is exactly the sort of writer who refutes common claims by critics of modern publishing that great authors of the past would never be published today; I'd be willing to bet that if Emily Brontë were alive today, she'd probably be reigning supreme over the likes of Anne Rice and Diana Gabaldon. (Yes, I totally think Emily would be writing historical romance/fantasy mash-ups, whereas Charlotte would probably be writing more traditional romances. And I still wouldn't want to read her books, but I'd say she wipes her feet on Rice and Gabaldon.)

Heathcliff: Hot or Not? Wuthering Heights on Film

Wikipedia lists like a gazillion adaptations of Wuthering Heights.

I watched seven.

(Netflix, you're killing me!)

Of all the classic books whose multiple film adaptations I have watched recently, Wuthering Heights probably has the most variety in its different film interpretations. There are entire sections of the book that many versions leave out. Several chop off everything before Mr. Earnshaw dies; others end the story when Cathy dies. In some versions, Heathcliff is a broody, handsome "bad boy" giving Cathy sultry looks and rolling in the heather with her -- in others, he's a dirty-faced violent savage that only a fellow savage (as Cathy is portrayed in the book) could love. There are also marked differences in how sympathetically Hindley and Edgar are portrayed. In most versions, Edgar is a pathetic wimp and Cathy uses him as a doormat. But in the book, he was basically a decent and even-tempered man who was too much in love with a woman he knew from the beginning didn't really love him. Most versions depict Hindley as he was in the book; a petty, jealous, wastrel who's not much less of a dick than Heathcliff. Some film versions, however, emphasize Hindley's insecurity more. After all, both his sister and his father seemed to prefer Heathcliff to the firstborn Earnshaw son; it's understandable that this was a bitter pill for a privileged son to swallow. It hardly justifies his being such an asshole -- indeed, everyone in the book is an asshole, and beyond all reasonable justification -- but Hindley one can almost feel sorry for.

All of them leave out most of the interactions between Catherine and Linton, sometimes making the forced marriage come literally out of nowhere, and seemingly between cousins who barely know each other. None of the film versions captured just what a horrible person Linton was in his own right, a sickly little beast who was every bit his father's son.

I started dividing the film versions into "Lockwood" and "No Lockwood." The versions that included the first-person narrator of the novel, Mr. Lockwood, usually preserved most of the details of Brontë's story, while the versions that left him out usually left out other essentials, sometimes leaving out the second generation entirely. These were also the versions that tended to leave out the worst aspects of Heathcliff's character and make him more sympathetic.

The 1967 BBC Serial

This was a four-episode TV serial, running just over three hours in total. It was filmed in black and white, which really works for this faithfully bleak adaptation. Like most BBC serials of the era, the actors seem more accustomed to theater than film, but they captured all the spitefulness, pettiness, and bitchiness of Brontë's characters. This film also showed just how effectively you can adapt a period piece on a low budget. There is no musical score at all -- just a soundtrack of constant, blowing wind. This version, being so long, was the most true to Brontë's novel; Lockwood appears, though he doesn't actually show up until the end.

The 1970 Film

This was one of the most romanticized versions, with pretty dresses and swelling bosoms and pretty-boy Timothy Dalton as Heathcliff. His acting was fine -- he made Heathcliff broody and smirky and malevolent -- but he's too dashing.

This adaptation was quite abridged and altered the story in a couple of substantial ways. It's implied that Nelly had a crush on Hindley. (It does make Nelly a meddlesome snitch, as she was in the book, something most of the movie versions gloss over.) More significantly, the director filmed an ending that's quite different from the one in the book -- it's not a bad ending, haunting and true to Brontë's vision if not her words, but like many of the abridged versions, it leaves out everything in the second half of the book involving the children of Heathcliff, Hindley, and Cathy.

The 1985 French film

This adaptation takes Wuthering Heights off the Yorkshire moors and sets it in the French countryside in the 1930s.

As an adaptation that reinterprets a classic by setting it in a different time and place, it has an entirely different style than Brontë's novel, and might be preferable to those who like Wuthering Heights as a romance. It actually makes the story sexy and sultry, while still preserving most of the characters and scenes in their essence. Being a "No Lockwood" version, it starts after Mr. Earnshaw is already dead and basically ends with Cathy's death.

The 1992 Film

Ralph Fiennes as Heathcliff... (Must... not... make.... Voldemort... joke...!)

(No, seriously, Heathcliff is so obviously Snape -- an unlovable shit who wastes his life pining for a woman who spurned him and taking his bitterness out on children for the sins of their parents.)

One of the few adaptations that starts as the book did, with Mr. Lockwood arriving at Wuthering Heights to come in on the backstory at the tail end. This is a lavish production, one of those high-budget costume dramas with what I call the "Highlander" look and feel (sinister long-haired men prowling about looking like they're going to draw swords and start beheading any moment).

This movie is a loose adaptation that keeps most of the major events in the book but very little of the original dialog, substituting lots of romantic interludes between Heathcliff and Cathy (including kissing!), and giving them poetic, impassioned expressions of love that are nothing like anything they said in the book. Much of the subtext of the characters' interactions was changed. This movie is probably one of the prettiest productions, but took the most liberties. (Not counting the MTV version below...)

The pretty costumes notwithstanding, there is little fidelity to the historical period in this film. Healthcliff and Cathy open-mouthed kissing! And Hareton walking around half-naked (giving bare-chested fan service to the female audience) in front of a lady would so not happen.

The Masterpiece Theatre Production (1999)

A two-hour movie produced by PBS's Masterpiece Theatre. Masterpiece Theatre tends to have higher production values than BBC serials, but lower fidelity to the source material.

This was a decent production, neither the best nor the worst of all the ones I watched. The most distracting aspect in this version was the actors in their late 30s playing teenage Cathy and Heathcliff; a couple of obvious adults running around acting as wild as Cathy and Heathcliff do sort of throws you out of the story. But it's pretty faithful to the novel, and keeps most of the important lines. Frankly, I found it probably the most unmemorable, with the least charismatic Heathcliff and a Cathy who was too made-up and devoid of any real passion.

The Masterpiece Classics Production (2009)

Masterpiece Classics is the same PBS company that used to be called Masterpiece Theatre, so this is basically a remake of the above production. This version actually starts with the second act of the novel, introducing us to young Catherine and Linton in the opening and plunging them into Heathcliff's schemes for vengeance, and then filling in the backstory.

This was a colorful production that watered down and sexified Brontë's story for a 21st century audience, a costume drama with a drum-beat soundtrack. The actors are better, less glammed, and more appropriate to their roles, than in the previous Masterpiece production, but the story is almost "based on" Brontë's Wuthering Heights rather than her story. It was very heavy on the romance and added lots of invented scenes, from the extraneous to the completely character-altering, mostly to make Heathcliff more sympathetic and Hindley extra-evil. Worth watching, but not a very faithful adaptation.

However, when it comes to unfaithful, dumbed-down adaptations, nothing can top...

MTV's Wuthering Heights (2003)

Fer real, dude. Wuthering Heights reinterpreted as a modern teen angst drama with music videos. In California. And "Heath" becomes a rock star.

I suppose there is something to be said for an adaptation that might get Coldplay and Nickelback fans reading 19th-century literature, but this was a really stupid movie with very pretty, very bad actors. (Kate delivers the "I am Heath" soliloquy like she's having an asthma attack.) It's only vaguely similar to the novel. The orphan Heath in this version is not a brooding dark-skinned "gypsy" but a brooding blue-eyed blonde with boy-band bangs. Nelly is removed entirely from this version -- in fact, pretty much every adult figure is absent, once Earnshaw dies in a laughable five-second scene where he clutches his chest and stares pop-eyed at the key light to let us know HE'S HAVING A HEART ATTACK OMG!

When I say adults are removed, I mean they're totally removed. It's like a sixteen-year-old's fantasy world where parentless teenagers live in big houses and attend parties and rock concerts but never go to school or cook or buy things or have any contact at all with the outside world.

In this version, Kate is an innocent (if empty-headed), passive plaything, batted between two men in a love triangle. Robbed of any agency, she's not even the manipulative bitch she was in the book; she just sort of stands by and waits to see which alpha-male will claim her. So the whole movie is basically a bunch of teenagers posturing and swaggering and making out and getting drunk.

Bonus Media Content: The Things You Discover on Wikipedia

You know how there are songs that you immediately recognize, have probably heard a hundred times, but never actually listened to the lyrics or known about their origins?

I like Kate Bush, but I never knew the title of this song. It's an entirely different experience listening to it now.

And if you are a serious Emily Brontë fan, there's a Wuthering Heights role-playing game!

Verdict: Wuthering Heights is one of those novels that most people love or hate. I didn't love it. It's gloomy and full of unpleasant characters, it's written in the stilted, formal prose of a sheltered young Victorian writer, and it's a "romance" only in the original, classic sense. But the moody atmosphere, an unsentimental plot of surprisingly subtlety, and one of the most memorable anti-heroes in English literature makes this a book that deserves to be read. You may not enjoy it, but it's one of those books you should read to understand its legacy and the debt owed by so many later writers: Heathcliff is a modern Campbellian archetype, and Emily Brontë was a genius for creating him.

This was my sixth assignment for the books1001 challenge. Join us and read and write reviews for all those books you've always wanted to read someday but never gotten around to.

Originally published 1847, approx. 116,570 words. Available for free at Project Gutenberg.

Wuthering Heights", Emily Brontë's only novel, is one of the pinnacles of 19th-century English literature. It's the story of Heathcliff, an orphan who falls in love with a girl above his class, loses her, and devotes the rest of his life to wreaking revenge on her family.

Crossposted to books1001 and bookish.

Wuthering Heights is one of those classics I'd never read, nor had I ever seen any of the movies, so all I really knew about this story was that it's a Victorian romance with a guy named Heathcliff whom people generally consider to be an asshole and who's the archetype of the modern "bad boy" romantic hero.

Apparently, this much-beloved book is considered by many to be a timeless romance. Anyone who thinks Wuthering Heights is a romance must suffer from the same brain damage that makes Edward Cullen dreamy and Severus Snape sexy. This is not a love story; it's a hate story. Everything that happens is motivated by hate: mostly Heathcliff's, but Heathcliff is like a black hole of hate who sucks everyone else into the orbit of his own hatred and makes them hateful, too; in the end, everyone spirals to their doom. For all of his speeches about how Cathy is his soul, Cathy's "I am Heathcliff" speech comes closer to the truth: the two of them don't so much love one another as feel such a desperate sense of possession for one another that their mutual obsession occludes all other feelings.

This is not a love story

The book begins when Mr. Earnshaw, master of Wuthering Heights, a gloomy estate on the Yorkshire moors, brings back an unexpected "present" from a trip to Liverpool: a "gypsy" orphan in his arms. He found it (yes, everyone refers to the boy as "it") on the streets, apparently parentless and starving, and brought the boy home.

‘And at the end of it to be flighted to death!’ he said, opening his great-coat, which he held bundled up in his arms. ‘See here, wife! I was never so beaten with anything in my life: but you must e’en take it as a gift of God; though it’s as dark almost as if it came from the devil.’

We crowded round, and over Miss Cathy’s head I had a peep at a dirty, ragged, black-haired child; big enough both to walk and talk: indeed, its face looked older than Catherine’s; yet when it was set on its feet, it only stared round, and repeated over and over again some gibberish that nobody could understand. I was frightened, and Mrs. Earnshaw was ready to fling it out of doors: she did fly up, asking how he could fashion to bring that gipsy brat into the house, when they had their own bairns to feed and fend for? What he meant to do with it, and whether he were mad? The master tried to explain the matter; but he was really half dead with fatigue, and all that I could make out, amongst her scolding, was a tale of his seeing it starving, and houseless, and as good as dumb, in the streets of Liverpool, where he picked it up and inquired for its owner. Not a soul knew to whom it belonged, he said; and his money and time being both limited, he thought it better to take it home with him at once, than run into vain expenses there: because he was determined he would not leave it as he found it. Well, the conclusion was, that my mistress grumbled herself calm; and Mr. Earnshaw told me to wash it, and give it clean things, and let it sleep with the children.

Mr. Earnshaw's daughter Cathy is fascinated by the orphan (whom they name Heathcliff), and they become lifelong friends. Cathy's brother Hindley is less enamored; he's immediately filled with jealousy and contempt. The obsessive love between Heathcliff and Cathy, and the grudge between Heathcliff and Hindley, who sees the orphan as supplanting his rightful place, fuels the rest of the story.

Heathcliff is often called a "gypsy." While of course you can take it for granted that Victorians were racist as all hell, one wonders whether most Victorians were unable to imagine non-gentry as anything other than an indistinguishable melting pot of dark-skinned people who all spoke gibberish, or if this was Emily Brontë's ignorance.

‘“What culpable carelessness in her brother!” exclaimed Mr. Linton, turning from me to Catherine. “I’ve understood from Shielders”’ (that was the curate, sir) ‘“that he lets her grow up in absolute heathenism. But who is this? Where did she pick up this companion? Oho! I declare he is that strange acquisition my late neighbour made, in his journey to Liverpool-a little Lascar, or an American or Spanish castaway.”

Supposedly, Edgar Linton figures it's equally likely that he's a gypsy, an American, a Spaniard, or a Lascar. As in many other interactions, there were parts of this book that didn't ring quite true to me, but it was hard to tell whether this was really the manner of thinking and acting at the time, or Brontë's fancy, as she had to imagine much of what the outside world was really like.

I bring this up not to bash Brontë for her racism (she was a sheltered vicar's daughter and probably never met another person outside her class) but because I just find it kind of interesting to trace the evolution of racial attitudes over time. Something a lot of modern readers may not be aware of is that in Victorian times, it wasn't just a different skin color or nationality that made you a different race; Victorians believed that the different social classes were practically different species as well. (This justified treating the lower classes like animals; they were thought to literally not feel or suffer the way the upper classes did, an attitude Charles Dickens addressed directly in his novels, which were much more critical of his own society.)

Likewise, modern readers tend to assume that anything described in an old classic is an authentic representation of the attitudes and people of that era, which may not always be so. Suppose someone two hundred years from now reads Twilight and assumes that Stephanie Meyer was actually describing how teenagers acted in the early 21st century?

Isn't it Byronic?

It's not Heathcliff's dubious lineage that makes him the despised cast-off of the Earnshaw household, but the fact that he is not a "gentleman"; his failure to be "raised" to Cathy's level, and his degradation compared to his step-brother Hindley, who went off to school. Of course, his situation is not helped by the fact that he's just naturally an asshole.

After reading the book (and then watching a bunch of film adaptations -- see below) I think the first point to observe is that Emily Brontë's Heathcliff is not at all romantic, and I don't think Brontë intended him to be. He doesn't once say a kind word to anyone throughout the book -- not to Mr. Earnshaw, the man who took him in and treated him like a son; not to Nelly, the nurse who takes care of him and Cathy and even enables his continued relationship with Cathy after she marries Edgar Linton; and not even to Cathy.

The most affectionate thing he ever says to her is that he'll refrain from doing violence on her say-so. Heathliff is an almost demonic creature who spends most of the book wreaking destruction and vengeance against anyone who's ever slighted him. ("Slighting" him includes being related to anyone he dislikes.) If not for the fact that he seems to love Cathy (albeit obsessively and spitefully, with that kind of hateful love that only severely damaged personalities can exhibit), he'd unquestionably be considered a sociopath.

It's true that Hindley starts treating Heathcliff like shit the moment his father dies, unleashing years of pent-up resentment and going out of his way to humiliate him. But it's hard to feel sorry for Heathcliff when even before that, he never showed the slightest gratitude or affection for anyone but Cathy. And when he returns to Wuthering Heights after his three years abroad, he's gone from sullen savage to psychopath. He destroys Hindley, deliberately raises Hareton as a brute, humiliates Edgar Linton, rapes and beats Isabella, and torments Cathy. After Cathy dies, he goes on bullying and abusing children for the crime of being alive, just to make their (dead) parents suffer.

Interestingly, considering Cathy dies only halfway through the book, a lot of people seem to think that Wuthering Heights is all about the relationship between Heathcliff and Cathy. There is an entire second act involving Cathy's daughter Catherine, Heathcliff's son Linton, and Hindley's son Hareton, in which Heathcliff's vengeance, obsession, and hatred comes full circle.

As with so many of these desperate, dark Victorian novels, much of the plot is driven by outright gratuitous cruelty; so many of the disasters that befall everyone could be avoided if just once, someone decided not to be loathsome.

The Unreliable Narrator and Reading Between the Lines

Something one would miss from experiencing Wuthering Heights only through the movie adaptations is that it's written in several layers. The ostensible narrator of the book is Mr. Lockwood, a tenant of Heathcliff's who comes along at the end of the story to rent Thrushcross Grange, and thus hears the story second-hand. He hears the story from Ellen Dean (Nelly), the housekeeper who served both the Earnshaws and the Lintons, who thus becomes the first-person narrator of many of the chapters. There are also chapters "narrated" by other characters, through Nelly, who is supposedly repeating letters she's received and conversations she's had word-for-word, a common literary device at the time.

What makes Nelly interesting is that she frequently makes asides about how she failed to do this or that, regretted something she said or didn't say, or realizes something was a mistake in hindsight -- but always absolves herself. If you pay close attention, you realize that Nelly was a bit of a gossip and a sneak, always looking for opportunities to tattle and stir up trouble, convinced that she was acting in the best interests of Cathy or Catherine. When you realize that by her own admission, she frequently acts out of cowardice, and sometimes acts out of pique, you begin to question how accurate her portrayal of the other characters may be. Clearly she doesn't like her fellow servant Joseph, so is he really the obstreperous Bible-thumping old coot he seems to be, or was Nelly perhaps embellishing the unpleasantness of his personality a bit? And could she likewise be villainizing Heathcliff unjustly?

Even Lockwood, who is only really "present" at the beginning and the end of the novel, in the bits he narrates shows signs of putting his own bias into the tale (such as his assessment of Catherine, whom he describes as a petty, spiteful brat when she fails to be impressed by him -- never mind that she's basically a prisoner in a household where everyone hates her -- and only gives a more pleasant description of her later).

This does give a bit more justification for the wildly varying interpretations the book has been given in film adaptations. And being a Victorian novel where there's a lot that couldn't be made explicit, critics have a great time coming up with "fanon" speculation. Did Heathcliff actually kill Hindley? Was Catherine actually Heathcliff's daughter? Several film versions make it pretty explicit that Heathcliff and Cathy were lovers, but in the book, there is no evidence that they really went that far, unless one reads liberally between the lines.

Emily Brontë the Author

Wuthering Heights got mixed reviews when it was published; some critics called it "immoral" and "pagan." Unlike her sisters Charlotte and Anne, Emily only ever wrote one novel. She was working on a second when she died the year after Wuthering Heights was published.

Wuthering Heights is full of death. Just about everyone dies young, in childbirth, or of drink and despair. Almost nobody gets a happy ending. Since this was pretty much how Emily and her entire family lived and died, it's not surprising that Wuthering Heights is a fantastically gloomy novel, both morbid and full of repressed fantasy, showing the same sort of imagination that the Brontës first conceived in their fantasy world of Gondal.

To be honest, I didn't much like Wuthering Heights as a story. If Emily Brontë had written other novels, I wouldn't be putting them on my TBR list. But I do think she was a genius, and you can see it in her writing, in the wild imagination and the subtext of her book, despite being written from what was essentially a fairly limited worldview.

Emily Brontë is exactly the sort of writer who refutes common claims by critics of modern publishing that great authors of the past would never be published today; I'd be willing to bet that if Emily Brontë were alive today, she'd probably be reigning supreme over the likes of Anne Rice and Diana Gabaldon. (Yes, I totally think Emily would be writing historical romance/fantasy mash-ups, whereas Charlotte would probably be writing more traditional romances. And I still wouldn't want to read her books, but I'd say she wipes her feet on Rice and Gabaldon.)

Heathcliff: Hot or Not? Wuthering Heights on Film

Wikipedia lists like a gazillion adaptations of Wuthering Heights.

I watched seven.

(Netflix, you're killing me!)

Of all the classic books whose multiple film adaptations I have watched recently, Wuthering Heights probably has the most variety in its different film interpretations. There are entire sections of the book that many versions leave out. Several chop off everything before Mr. Earnshaw dies; others end the story when Cathy dies. In some versions, Heathcliff is a broody, handsome "bad boy" giving Cathy sultry looks and rolling in the heather with her -- in others, he's a dirty-faced violent savage that only a fellow savage (as Cathy is portrayed in the book) could love. There are also marked differences in how sympathetically Hindley and Edgar are portrayed. In most versions, Edgar is a pathetic wimp and Cathy uses him as a doormat. But in the book, he was basically a decent and even-tempered man who was too much in love with a woman he knew from the beginning didn't really love him. Most versions depict Hindley as he was in the book; a petty, jealous, wastrel who's not much less of a dick than Heathcliff. Some film versions, however, emphasize Hindley's insecurity more. After all, both his sister and his father seemed to prefer Heathcliff to the firstborn Earnshaw son; it's understandable that this was a bitter pill for a privileged son to swallow. It hardly justifies his being such an asshole -- indeed, everyone in the book is an asshole, and beyond all reasonable justification -- but Hindley one can almost feel sorry for.

All of them leave out most of the interactions between Catherine and Linton, sometimes making the forced marriage come literally out of nowhere, and seemingly between cousins who barely know each other. None of the film versions captured just what a horrible person Linton was in his own right, a sickly little beast who was every bit his father's son.

I started dividing the film versions into "Lockwood" and "No Lockwood." The versions that included the first-person narrator of the novel, Mr. Lockwood, usually preserved most of the details of Brontë's story, while the versions that left him out usually left out other essentials, sometimes leaving out the second generation entirely. These were also the versions that tended to leave out the worst aspects of Heathcliff's character and make him more sympathetic.

The 1967 BBC Serial

This was a four-episode TV serial, running just over three hours in total. It was filmed in black and white, which really works for this faithfully bleak adaptation. Like most BBC serials of the era, the actors seem more accustomed to theater than film, but they captured all the spitefulness, pettiness, and bitchiness of Brontë's characters. This film also showed just how effectively you can adapt a period piece on a low budget. There is no musical score at all -- just a soundtrack of constant, blowing wind. This version, being so long, was the most true to Brontë's novel; Lockwood appears, though he doesn't actually show up until the end.

The 1970 Film

This was one of the most romanticized versions, with pretty dresses and swelling bosoms and pretty-boy Timothy Dalton as Heathcliff. His acting was fine -- he made Heathcliff broody and smirky and malevolent -- but he's too dashing.

This adaptation was quite abridged and altered the story in a couple of substantial ways. It's implied that Nelly had a crush on Hindley. (It does make Nelly a meddlesome snitch, as she was in the book, something most of the movie versions gloss over.) More significantly, the director filmed an ending that's quite different from the one in the book -- it's not a bad ending, haunting and true to Brontë's vision if not her words, but like many of the abridged versions, it leaves out everything in the second half of the book involving the children of Heathcliff, Hindley, and Cathy.

The 1985 French film

This adaptation takes Wuthering Heights off the Yorkshire moors and sets it in the French countryside in the 1930s.

As an adaptation that reinterprets a classic by setting it in a different time and place, it has an entirely different style than Brontë's novel, and might be preferable to those who like Wuthering Heights as a romance. It actually makes the story sexy and sultry, while still preserving most of the characters and scenes in their essence. Being a "No Lockwood" version, it starts after Mr. Earnshaw is already dead and basically ends with Cathy's death.

The 1992 Film

Ralph Fiennes as Heathcliff... (Must... not... make.... Voldemort... joke...!)

(No, seriously, Heathcliff is so obviously Snape -- an unlovable shit who wastes his life pining for a woman who spurned him and taking his bitterness out on children for the sins of their parents.)

One of the few adaptations that starts as the book did, with Mr. Lockwood arriving at Wuthering Heights to come in on the backstory at the tail end. This is a lavish production, one of those high-budget costume dramas with what I call the "Highlander" look and feel (sinister long-haired men prowling about looking like they're going to draw swords and start beheading any moment).

This movie is a loose adaptation that keeps most of the major events in the book but very little of the original dialog, substituting lots of romantic interludes between Heathcliff and Cathy (including kissing!), and giving them poetic, impassioned expressions of love that are nothing like anything they said in the book. Much of the subtext of the characters' interactions was changed. This movie is probably one of the prettiest productions, but took the most liberties. (Not counting the MTV version below...)

The pretty costumes notwithstanding, there is little fidelity to the historical period in this film. Healthcliff and Cathy open-mouthed kissing! And Hareton walking around half-naked (giving bare-chested fan service to the female audience) in front of a lady would so not happen.

The Masterpiece Theatre Production (1999)

A two-hour movie produced by PBS's Masterpiece Theatre. Masterpiece Theatre tends to have higher production values than BBC serials, but lower fidelity to the source material.

This was a decent production, neither the best nor the worst of all the ones I watched. The most distracting aspect in this version was the actors in their late 30s playing teenage Cathy and Heathcliff; a couple of obvious adults running around acting as wild as Cathy and Heathcliff do sort of throws you out of the story. But it's pretty faithful to the novel, and keeps most of the important lines. Frankly, I found it probably the most unmemorable, with the least charismatic Heathcliff and a Cathy who was too made-up and devoid of any real passion.

The Masterpiece Classics Production (2009)

Masterpiece Classics is the same PBS company that used to be called Masterpiece Theatre, so this is basically a remake of the above production. This version actually starts with the second act of the novel, introducing us to young Catherine and Linton in the opening and plunging them into Heathcliff's schemes for vengeance, and then filling in the backstory.

This was a colorful production that watered down and sexified Brontë's story for a 21st century audience, a costume drama with a drum-beat soundtrack. The actors are better, less glammed, and more appropriate to their roles, than in the previous Masterpiece production, but the story is almost "based on" Brontë's Wuthering Heights rather than her story. It was very heavy on the romance and added lots of invented scenes, from the extraneous to the completely character-altering, mostly to make Heathcliff more sympathetic and Hindley extra-evil. Worth watching, but not a very faithful adaptation.

However, when it comes to unfaithful, dumbed-down adaptations, nothing can top...

MTV's Wuthering Heights (2003)

Fer real, dude. Wuthering Heights reinterpreted as a modern teen angst drama with music videos. In California. And "Heath" becomes a rock star.

I suppose there is something to be said for an adaptation that might get Coldplay and Nickelback fans reading 19th-century literature, but this was a really stupid movie with very pretty, very bad actors. (Kate delivers the "I am Heath" soliloquy like she's having an asthma attack.) It's only vaguely similar to the novel. The orphan Heath in this version is not a brooding dark-skinned "gypsy" but a brooding blue-eyed blonde with boy-band bangs. Nelly is removed entirely from this version -- in fact, pretty much every adult figure is absent, once Earnshaw dies in a laughable five-second scene where he clutches his chest and stares pop-eyed at the key light to let us know HE'S HAVING A HEART ATTACK OMG!

When I say adults are removed, I mean they're totally removed. It's like a sixteen-year-old's fantasy world where parentless teenagers live in big houses and attend parties and rock concerts but never go to school or cook or buy things or have any contact at all with the outside world.

In this version, Kate is an innocent (if empty-headed), passive plaything, batted between two men in a love triangle. Robbed of any agency, she's not even the manipulative bitch she was in the book; she just sort of stands by and waits to see which alpha-male will claim her. So the whole movie is basically a bunch of teenagers posturing and swaggering and making out and getting drunk.

Bonus Media Content: The Things You Discover on Wikipedia

You know how there are songs that you immediately recognize, have probably heard a hundred times, but never actually listened to the lyrics or known about their origins?

I like Kate Bush, but I never knew the title of this song. It's an entirely different experience listening to it now.

And if you are a serious Emily Brontë fan, there's a Wuthering Heights role-playing game!

Verdict: Wuthering Heights is one of those novels that most people love or hate. I didn't love it. It's gloomy and full of unpleasant characters, it's written in the stilted, formal prose of a sheltered young Victorian writer, and it's a "romance" only in the original, classic sense. But the moody atmosphere, an unsentimental plot of surprisingly subtlety, and one of the most memorable anti-heroes in English literature makes this a book that deserves to be read. You may not enjoy it, but it's one of those books you should read to understand its legacy and the debt owed by so many later writers: Heathcliff is a modern Campbellian archetype, and Emily Brontë was a genius for creating him.

This was my sixth assignment for the books1001 challenge. Join us and read and write reviews for all those books you've always wanted to read someday but never gotten around to.