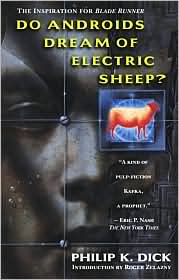

Dick, Philip K.: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Writer: Philip K. Dick

Genre: Science Fiction

Pages: 244

No, I've never read Philip K. Dick before now. Yes, I know that makes me a bad science fiction reader. But hey, at least I'm taking steps to correct this horrible sin, right?

So why now, and why Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? No, I didn't want to read the source material Bladerunner was based on, because I haven't seen Bladerunner (I know, I know, that's something else I mean to correct). Rather, you can blame John Scalzi for this. He published The Android's Dream a couple years ago, and since I'm such a big fan of his work, I obviously really wanted to read this one. However, even though I'd never read Dick, even I knew what Scalzi's title referred to, and I had a feeling that I simply wouldn't enjoy the Scalzi near as much if I didn't have the Dick under my belt first.

Wow, that just sounded really, really wrong, especially since I'm female. ANYWAY.

So in order to read the Scalzi, I had to read this first. So I did. And as usual, I find reading an SF classic something of a oddity given my age and familiarity with current pop culture SF. Many of the themes presented in Dick's novel I've seen before. What makes a human truly human? I've got the current Battlestar Galactica television series to thank for that. And that's just the tip of the iceberg that makes reading this book such an odd experience for me. That's not to dismiss the value of this book by any means (after all, this book is a classic, the roots of modern SF like BSG), and certainly, Dick does stuff here I haven't seen that I found to be very interesting. So let's talk.

The premise: androids are illegal on Earth, and those that've escaped Mars to hideout on Earth get a rather rude awakening in the form of bounty hunters like Rick Deckard. After the fall of a colleague, he's after six very sentient and very dangerous androids, and what makes them so dangerous is that it's getting harder and harder to tell them apart from humans.

Spoilers ahead.

Empathy. That's the difference between human and android. And it's a fascinating detail, especially in a world that animals are such PRIZED possessions, so much so that people will even get electronic versions so that they can keep up appearances in society. At first, the full impact of this didn't hit me, the difference between android and human, but it did at the end when Pris started cutting off the legs of a spider just to see if it could still walk. Talk about horrible. Rick surmises that the spider was perhaps electronic, but that's really not the point. The point was that androids had no care or affection for creatures other than themselves (and by that, I mean their individual selves), and that scene said it all.

There's a lot of good stuff in this rather short book. The question of what it means to be human, what it means to feel empathy with fellow living creatures, why androids are so low on the food chain, so to speak. Animals are the most prized sentience on the planet. Then humans. Then androids. And androids are expected to be shot on sight.

I loved Rick's conflict, especially when he realized that 1) he had empathy for female androids and 2) that he's not quite the bounty hunter he thought he was. I know the big twist in Bladerunner is that the main character is an android and he didn't know it, so I kept expecting the same thing to pop up here, but it didn't. And that's just as well. It makes his fling with Rachael all the more important, particularly her actions at the end when she pushes the goat off the roof, just to get back at him because he loves the goat above all things, even his wife, and even her.

But there's a lot that puzzled me about this book, and most of it dealt with timeline. It seemed that Rachael Rosen didn't know she was an android until Rick performed the test on her, yet later in the book we learn she's slept with several other bounty hunters in order to nix their android-killing habits. How could she do this if she just learned she was an android herself? And since androids have such short life-spans (if left to their own devices), it doesn't seem like Rachael's had the time to do such things. She's already two and has two more years to go if she isn't killed, so this looks like a hiccup in the plot, or maybe I just misread something important.

Which is possible, btw. I found myself struggling with the rhythms of Dick's prose and the casual chain between action and reaction, as well as character motivation. The latter not often, but sometimes. And I think because of that I found myself juggling what appeared to be plot holes.

Or simply flaws in logic. Animals are a prized possession, but people like Isidor, who have the ability to bring the dead back to life, have that ability shunted off. They're exiled, considered specials, which is just one step up from being an android in most people's opinions. I don't get that. I mean I really don't get that whole aspect of the plot. Why are specials called chickenheads or antheads, and in the case of Isidor, why does him having a lower IQ make him bad? Why is his talent something to be taken away rather than revered, given the worship of animal life that Dick has so clearly set up? Or is that the whole point, the irony in a society that worships animal life but refuses to bring it back from the dead?

Hard to say. Buster Friendly I understood for the most part, and Mercer I did too, even after it was exposed that Mercer was a fake. I didn't mind, really, until Mercer magically appeared outside the empathy box to guide Rick during the climatic scene. That really, really threw me, and it made all the spiritual exploration at the VERY end come across as gibberish, because I had no basis for reality, and everything I was reading contradicted Buster Friendly's revelations, revelations that were very grounded. So yes, by the end, I was a little lost in that regard.

Certainly, though, the Dick's androids are the inspiration, if not the root of, the humanoid cylons in BSG, which--again--made many of the questions raised in this book moot because I was already familiar with such thought experiments, so to speak. And unlike Dick's andys, cylons do have empathy, so from an historical SF point of view, it was cool to see how this particular convention has evolved over the years.

My Rating

Give It Away: don't get me wrong. It's a good read and worth reading, especially if you fancy yourself an SF expert, but it's not the kind of book that I personally feel the need to hold on to and read again. I'll probably hold on to it for history's sake, in that it's clearly an SF classic, and I may want to return to the text again, but if you're reading for pure entertainment, it's not a necessary book to keep. I'm glad I read it, and I plan on reading more of Dick's material. But I'll take my time with it, because there's something about this book and his writing style that is dated, in a way that I didn't notice when I read Alfred Bester. Hard to say why, but that's the way it is. :)

Next up:

Book: The Android's Dream by John Scalzi

Graphic Novel: V for Vendetta by Alan Moore