Gemeinda saga

Lo! A tale the magpie brought here, carried on its pointed tail feathers.

In a kingdom far and distant, by a river rude and rancid, in the royal city dwelt there Gemeinda of the Chaldeans. And in her charge, not merely one school but a gymnasium there also stood - both private halls of learning, for which were silvered riches ample. Though, in truth, they taught but little, matters useful scantly featured. And the king of that domain lived without a crown upon him, filling up his lands and holdings with fierce hordes of savage strangers - fierce in face and dark in spirit.

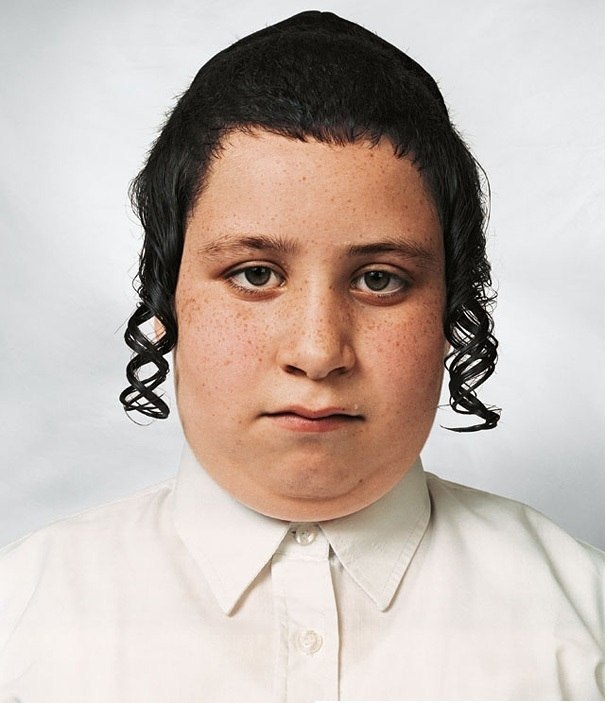

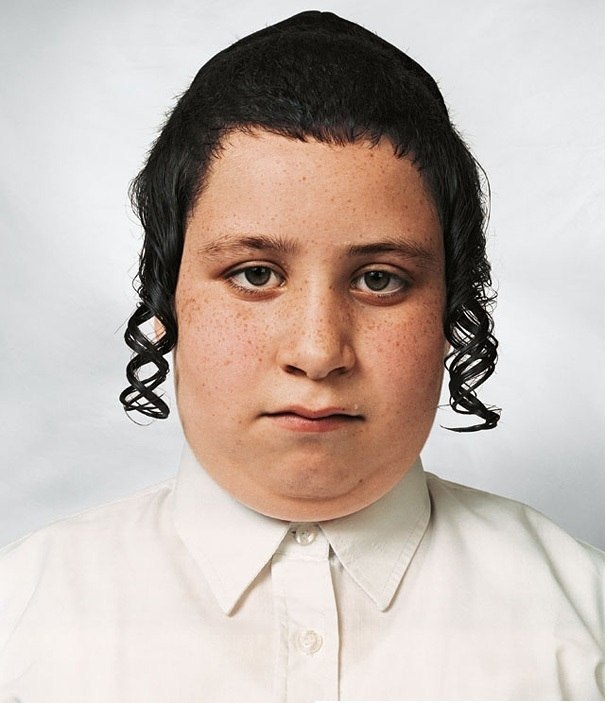

Thus, the Chaldean’s blessed children weren’t taught much in those fine halls, rather hidden from barbarians. At the helm of this fine schoolhouse stood one Ekstadt, a fiddler and an idler - known for verse in Yiddish muttered, known for loves most ill-esteemed. How it was that he, dear reader, came to be the sage and leader of the Chaldean’s school of learning, that’s a tale left darkly silent.

Yet in Gemeinda’s school of wonders, more marvels still were known to wander. For a third of those young students were Chaldean in no way; custom in this land permitted such inclusion of all folk. Strange it was, but true as ever, that among the native clansmen, some would send their sons and daughters to learn science by Chaldeans.

Now the time was one of warfare, fought far off in lands forbidding, where the tribes of Chaldeans clashed and met cruel defeat, blood and bitter. Gathered then the mighty Chaldeans, raised their arms and came avenging. Swiftly their swords cast punishment upon their foe, the Saracens (those same foes in neighbored lands around Gemeinda). As was righteous, their towns and meadows burned as judgment for their raids.

This, the tale’s beginning only; now the true tale blooms and branches.

When that anniversary came of that battle grim and gory, it was then in fair Gemeinda that a solemn feast was planned. Diak, the clerk, with voice austere, told of plans before the gathering. Then, young maiden rose to counter - let us call her Adolphina - and with bold stance spoke, declaring that the tribes of Chaldeans sin against the holy spirits - they whose names were clear and mighty: Diversity, Social Justice, and, above all, Ecology.

Chaldean youths, they grumbled softly, though one voice rang louder than the others, monkish lad who here we’ll call Zyama. For his cry against Adolphina, her heart darkened, wrathful brewing. A friend of basurman brigands, she sought four youths to plot a thumping; thus they leapt upon poor Zyama outside the hall in sight of all, bruising him with mighty blows but sparing life. And none rose to Zyama’s aid.

Healed in time, good Zyama, stumbling, buried deep his grievous beating, keeping silent as the custom. Yet when Zyama next did see her, Adolphina, fiery-angered, said her nose was twisted, ugly, making brave as Cyrano. But Adolphina heard not well the finer parts of his intention (her own mind was simple, hollow, like a cork afloat in water), and with speed she sought a healer - Baba Barikha, famed counselor, she who wrote a fateful verdict: Adolphina’s spirit shattered, and she’d ne’er be wed or cherished. Armed with scroll of broken psyche, swift to Ekstadt’s door she hurried, pouring forth a stream of grievance, as was custom in those borders.

Quick to tell a tale, it’s said, but slow to settle wrong with right. Called then Ekstadt forth a council, but he gave no word or reason. Summoned Zyama’s honored mother, praised her son yet scolded loudly, chanted verses round the fires, danced and stamped and struck the tambour; yet amid the grief and shouting, not a single word was whispered of the beating that had happened.

And in grandest culmination, Ekstadt, fierce and frowning darkly, stood before them, spake pronouncing that young Zyama should be tethered, cast away in shame and exile from Gemeinda’s walls forever - then was gone before her wailing. Left alone, the mother mourned there.

To one school she ran, then others; none would take her son, the Zyama. Year was ending; fate grew colder. No more hope for school, it seemed. Then at last, his mother, sorrowed, went unto a mystic, elder, long of beard and deep of learning, steeped in stargazing and secrets, of high craft and ancient lore. She with streaming tears besought him, bathed his shoes in tears and tokens, sprinkled gold and vowed them vengeance - vengeance not against the schoolhouse, but ’gainst all Gemeinda’s leaders.

Together forged they scrolls of grievance, long recounting Zyama’s burden, sent those scrolls unto all corners of the kingdom’s highest courts.

Whether justice came to Zyama, no one knew, yet in two moons’ time, Zyama once again was welcomed. Diaks, those clerks of judgment’s council, one by one in shame bowed lowly, came to Zyama, humbly pleading, took back all they’d laid against him. Yet his tenth year Zyama served twice, though still Ekstadt called him often to his room for close discussions of salvation’s deeper mysteries (perhaps more or maybe less). Yet Zyama’s mother, stern and righteous, brandished warning to his teachers, swore by powers of high counsel to unleash inspection’s fury. So the time for soul’s salvation ended swift and all was silenced.

And there ends the tale of Zyama - what became of him, who knows?

In a kingdom far and distant, by a river rude and rancid, in the royal city dwelt there Gemeinda of the Chaldeans. And in her charge, not merely one school but a gymnasium there also stood - both private halls of learning, for which were silvered riches ample. Though, in truth, they taught but little, matters useful scantly featured. And the king of that domain lived without a crown upon him, filling up his lands and holdings with fierce hordes of savage strangers - fierce in face and dark in spirit.

Thus, the Chaldean’s blessed children weren’t taught much in those fine halls, rather hidden from barbarians. At the helm of this fine schoolhouse stood one Ekstadt, a fiddler and an idler - known for verse in Yiddish muttered, known for loves most ill-esteemed. How it was that he, dear reader, came to be the sage and leader of the Chaldean’s school of learning, that’s a tale left darkly silent.

Yet in Gemeinda’s school of wonders, more marvels still were known to wander. For a third of those young students were Chaldean in no way; custom in this land permitted such inclusion of all folk. Strange it was, but true as ever, that among the native clansmen, some would send their sons and daughters to learn science by Chaldeans.

Now the time was one of warfare, fought far off in lands forbidding, where the tribes of Chaldeans clashed and met cruel defeat, blood and bitter. Gathered then the mighty Chaldeans, raised their arms and came avenging. Swiftly their swords cast punishment upon their foe, the Saracens (those same foes in neighbored lands around Gemeinda). As was righteous, their towns and meadows burned as judgment for their raids.

This, the tale’s beginning only; now the true tale blooms and branches.

When that anniversary came of that battle grim and gory, it was then in fair Gemeinda that a solemn feast was planned. Diak, the clerk, with voice austere, told of plans before the gathering. Then, young maiden rose to counter - let us call her Adolphina - and with bold stance spoke, declaring that the tribes of Chaldeans sin against the holy spirits - they whose names were clear and mighty: Diversity, Social Justice, and, above all, Ecology.

Chaldean youths, they grumbled softly, though one voice rang louder than the others, monkish lad who here we’ll call Zyama. For his cry against Adolphina, her heart darkened, wrathful brewing. A friend of basurman brigands, she sought four youths to plot a thumping; thus they leapt upon poor Zyama outside the hall in sight of all, bruising him with mighty blows but sparing life. And none rose to Zyama’s aid.

Healed in time, good Zyama, stumbling, buried deep his grievous beating, keeping silent as the custom. Yet when Zyama next did see her, Adolphina, fiery-angered, said her nose was twisted, ugly, making brave as Cyrano. But Adolphina heard not well the finer parts of his intention (her own mind was simple, hollow, like a cork afloat in water), and with speed she sought a healer - Baba Barikha, famed counselor, she who wrote a fateful verdict: Adolphina’s spirit shattered, and she’d ne’er be wed or cherished. Armed with scroll of broken psyche, swift to Ekstadt’s door she hurried, pouring forth a stream of grievance, as was custom in those borders.

Quick to tell a tale, it’s said, but slow to settle wrong with right. Called then Ekstadt forth a council, but he gave no word or reason. Summoned Zyama’s honored mother, praised her son yet scolded loudly, chanted verses round the fires, danced and stamped and struck the tambour; yet amid the grief and shouting, not a single word was whispered of the beating that had happened.

And in grandest culmination, Ekstadt, fierce and frowning darkly, stood before them, spake pronouncing that young Zyama should be tethered, cast away in shame and exile from Gemeinda’s walls forever - then was gone before her wailing. Left alone, the mother mourned there.

To one school she ran, then others; none would take her son, the Zyama. Year was ending; fate grew colder. No more hope for school, it seemed. Then at last, his mother, sorrowed, went unto a mystic, elder, long of beard and deep of learning, steeped in stargazing and secrets, of high craft and ancient lore. She with streaming tears besought him, bathed his shoes in tears and tokens, sprinkled gold and vowed them vengeance - vengeance not against the schoolhouse, but ’gainst all Gemeinda’s leaders.

Together forged they scrolls of grievance, long recounting Zyama’s burden, sent those scrolls unto all corners of the kingdom’s highest courts.

Whether justice came to Zyama, no one knew, yet in two moons’ time, Zyama once again was welcomed. Diaks, those clerks of judgment’s council, one by one in shame bowed lowly, came to Zyama, humbly pleading, took back all they’d laid against him. Yet his tenth year Zyama served twice, though still Ekstadt called him often to his room for close discussions of salvation’s deeper mysteries (perhaps more or maybe less). Yet Zyama’s mother, stern and righteous, brandished warning to his teachers, swore by powers of high counsel to unleash inspection’s fury. So the time for soul’s salvation ended swift and all was silenced.

And there ends the tale of Zyama - what became of him, who knows?