The Multiverse as Asylum: Madness and Neo-Baroque Fandom

Title: The Multiverse as Asylum: Madness and Neo-Baroque Fandom

Genre: Meta

Word count: 6,200 (Long meta is long)

Rating: G

Warnings: None

Summary: In Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment, Angela Ndalianis shows how current media, particularly science fiction film franchises, reflect the aesthetics of the seventeenth-century baroque. Using Ndalianis’s definitions of the neo-baroque, I will show that if media is neo-baroque, fandom is even more so. I argue that there is a connection between the prevailing view of the baroque as chaotic, excessive, and unreasonable, and the prevailing view of fans as crazy--fandom is viewed as crazy largely because it is neo-baroque, and the neo-baroque nature of that craziness makes the madness of fandom a productive madness. Fan scholars, however, seem to feel the need to justify the study of fandom by normalizing fandom, and saying that “everyone is a fan.” On the contrary, what we should be doing is accepting that fandom is mad, and re-conceptualizing that madness as an alternative way to think and respond to media. Fandom challenges dominant ideas of reason, storytelling, authorship, and economics, and learning to respond to media through fandom--learning to enter into the madness of fandom--provides a means to think in different ways.

-

First, a few words about the context of this essay. It was written for a university class about madness and the politics of knowledge, which largely explored the ways madness can alternatively be seen as a failure to communicate in “normal” ways. We talked about Michel Foucualt’s theories of psychiatric power, various works about bipolar disorder and autism, the interrelation between psychology and the body, emotion vs. reason, psychotropic drugs, and (most relevant for this essay) the aesthetics of seventeenth-century baroque art. I think knowing that this was written within the context of an ongoing discussion about madness is fairly important for understanding why I wrote this the way I did. I’ve made some edits, since I don’t need to explain fandom to an audience of fans. However, it seems necessary to the arguments to leave a lot of this as it is, so if some of my examples seem obvious to you, it’s because they seem equally obvious to me from my position as a fan. I explain things the way I do because it’s useful to make explicit the relationship I see between fandom and the neo-baroque, and because this was not originally written for an audience of fans.

In Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment, Angela Ndalianis shows how current media, particularly science fiction film franchises, reflect the aesthetics of the seventeenth-century baroque. Using Ndalianis’s definitions of the neo-baroque, I will show that if media is neo-baroque, the fan responses to it are even more so. Fan culture is, in structure and practice, profoundly neo-baroque. I argue that there is a connection between the prevailing view of the baroque as chaotic, excessive, and unreasonable, and the prevailing view of fans as crazy--fandom is viewed as crazy largely because it is neo-baroque, and the neo-baroque nature of that craziness makes the madness of fandom a productive madness. Fan scholars, however, seem to feel the need to justify the study of fandom by normalizing fandom, and saying that “everyone is a fan.” On the contrary, what we should be doing is accepting that fandom is mad, and re-conceptualizing that madness as an alternative way to think and respond to media. Fandom challenges dominant ideas of reason, storytelling, authorship, and economics, and learning to respond to media through fandom--learning to enter into the madness of fandom--provides a means to think in different ways.

Since I can’t assume you’ve read my source material, as I did in the original paper, I’m going to give a brief tour of Angela Ndalianis’s book, Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment, and also talk a bit about baroque art. If you’re interested in reading Ndalianis, I have PDFs of the introduction and chapter one, and chapters four and five, so just drop me a line and I’ll send them along.

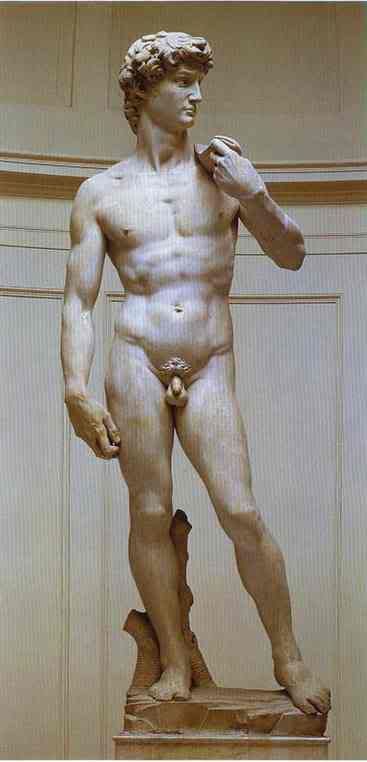

The baroque is a period in art--including sculpture, theatre, music, architecture, painting, literature and dance--situated roughly in the seventeenth century, in between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. It’s characterized by extravagance, excessiveness, repetition, extension or breaking of the frame, activity, and variation. One illustrative example of baroque art Ndalianis uses is the difference between Michelangelo’s statue of David (1504) and Bernini’s statue of David (1624). Whereas Michelangelo’s David only has a couple of obvious viewpoints (back, front, one side), with Bernini’s David there is no obvious point of view, no side from which you can see everything going on. Michelangelo’s David is not in motion, whereas Bernini’s David is. Because Bernini’s statue is in motion, and because the viewer has to walk around to see all of it, it interacts with the viewer in a way Michelangelo’s statue does not. Interacting with the audience is another key feature of the baroque.

Another of Ndalianis’s examples of baroque art is the ceiling of the Church of St. Ignazio in Rome, painted by Andrea Pozzo between 1685 and 1694. Because of the perspective in which the ceiling is painted, if you look at it from the right angle it looks as though there is a vaulted ceiling which extends up to heaven. In fact the ceiling is flat, but the real architecture of the church flows naturally into painted architecture. If you look at the ceiling from different angles, however, the perspective looks wrong and jarring. This isn’t a flaw, but a way to point out the illusion, and to bring to light the questionable nature of reality. The painted ceiling breaks through the framework of real physical architecture. The ceiling also relies on interaction with the viewer, because it matters where the viewer stands when they look at the ceiling.

Particularly important to the relationship between fandom and the baroque is the fact that baroque art has a long history of being devalued.

Although when the term "baroque" was originally applied to define the art and music of the seventeenth century is not known, its application in this way--and denigratory associations--gathered force during the eighteenth century. During this time, "baroque" implied an art or music of extravagance, impetuousness, and virtuosity, all of which were concerned with stirring the affections and senses of the individual. The baroque was believed to lack the reason and discipline that came to be associated with neoclassicism and the era of the Enlightenment.... (Ndalianis 7)

Wikipedia’s article about the baroque notes that in modern usage “baroque” is usually applied pejoratively. Baroque art was not considered worthy of study in art history for a very long time. Modern media which follows baroque aesthetics has a similar tendency to be devalued, as you know if you’ve spent any time trying to justify your participation in fandom, or if you look at the way the science fiction universes Ndalianis discusses are generally not taken very seriously.

Ndalianis shows that “particular features of a baroque poetics emerged:

minimal or lack of concern with plot development and a preference for a multiple and fragmented structure that recalls the form of a labyrinth; open rather than closed form; a complexity and layering evident, for example, in the merging of genres and literary forms such as poetry and the novel …. a view of the illusory nature of the world--a world as theatre, a virtuosity revealed through stylistic flourish and allusion; and a self-reflexivity that requires active audience engagement. (15)

Ndalianis identifies contemporary media as baroque through many different examples. One of these is the world of Batman, which exists in several different comic books, crossovers with other comic book universes, multiple movies over several decades, television series, and video games (34). The Batman universe exists in multiple media and multiple retellings of the same story, and has existed since the 1930’s. People keep retelling it because the characters continue to be interesting and different people want to continue to make their own interpretation of them. New Batman films, comics, or games are variations on a theme--a feature characteristic of baroque music (see the embedded video below). Other science fiction universes, such as Star Wars, Jurassic Park, and Alien, are structured similarly. These universes are complex, but the body of material created by fans about any of them is even more so. To me, fandom is so relevant and clear an example of the neo-baroque that I felt it was a blatant omission from Ndalianis’s work.

Neo-Baroque Fandom

“Fandom” in the context of this paper is meant to connote fan culture and communities, not the state of being a fan--more along the lines of “kingdom” than “stardom”. Any given fandom is the community centered around a particular originating text, whether that text is a single book or a collection of multiple stories within a single universe. The work of fandom is to interpret its text--its canon--and to spell out its interpretations, not (as literary theory spells out interpretations) in an essay, but in the same form as the original--in a story. Fans interpret the characters, the plots, and the world of their source material, and they tell the stories that result out of these interpretations through fiction, art, music, and film. In the Ndalianis passage quoted above, “active audience engagement” is listed as one of the main features of the baroque. Fan work is perhaps the most active engagement possible for an audience.

According to one participant in a survey of fan studies scholars, what distinguishes a fan of a text from a consumer of a text is that the fan “develops a personal attachment to a particular media artifact or ‘star’ and actively engages in a multiplicity of levels of creation that transcends or could even transform the ‘original’ text, character, or star persona” (Harrington and Bielby 186). Multiplicity is an important feature of the baroque. What makes fandom even more multiple than media universes like Batman is the fact that the creations of fandom are not required to be coherent. That is, an infinite number of stories can be told because they are not required to agree with any previous stories, or even completely with the canon. Internal consistency may or may not be a concern of retellings of the Batman story, but it is generally important that a retelling or a sequel not completely change something that was established in a previous story. In fandom, no such rule applies.

Fan authors are often explicit about their relationship to the real, canonical texts: the fan creations lack the authority of official texts. Because they are not canonical, fan stories can offer a thousand different ways that Mulder and Scully first slept together, none of which contradict the others, or one author can write “Five Things That Never Happened”--five alternate histories for a favorite character, all of which are, as the title states, repudiated by the author (Because AUs Make Us Happy n.d.). Lack of authority, which stems from lack of authorization, allows a freedom unavailable to an official canon striving for internal consistency. (Tushnet 67)

Thus, fandom has far more freedom in its multiplicity than the canonical, authorized texts do.

Another key feature of the neo-baroque is its seriality.

The use of multiple narrative centers (multiple originals) typical of seriality requires a reconsideration of traditional perceptions of linearity and closed narrative form. Neo-baroque seriality demands that a single linear framework no longer dominate the whole. Operating on the impetus of a repetitive drive, the baroque work produces "an aesthetic of repetition," and it is precisely this aesthetic of repetition that underlies the logic of the serial whole and its relationship to the fragment. (Ndalianis 69)

The multiplicity of fandom is the perfect environment for this “aesthetics of repetition” and seriality. Commonly, there will be moments in canon--lines of dialogue, events referenced but not shown, and so on--which prompt multiple fan writers to interpret those possible stories in their own way, regardless of the number of people who have already done so. One example is a line in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, when Dumbledore tells Sirius Black to “lie low at Lupin’s for a while” (Rowling 713). This created an entire genre of Harry Potter fan fiction, in which stories detail the time Sirius spends “lying low at Lupin’s” (Grossman). Though these stories all follow the same premise and roughly the same plot, the many possible interpretations of the characters allow for many retellings.

Fandom breaks boundaries, whether between diegetic and audience space, between author and reader, or between narratives.

The central characteristic of the baroque that informs this study is this lack of respect for the limits of the frame. Closed forms are replaced by open structures that favor a dynamic and expanding polycentrism. Stories refuse to be contained within a single structure, expanding their narrative universes into further sequels and serials. Distinct media cross over into other media, merging with, influencing, or being influenced by other media forms. (Ndalianis 25)

A common feature of fandom is this tendency to ignore the frame. As long as characters remain recognizable, there are no limits to what setting they can be placed in. Alternate Universe (AU) fan fiction is one way of expanding or moving the frame. An AU story might be one of several things. It might change one event in the original canon and explore how later events would go differently under those circumstances, it might transplant the characters into a different environment (a different part of history, for example), or it might change a particular feature of the characters (gender, occupation, etc.) (“Alternate Universe”). Another way of breaking the frame is crossover fan fiction, art, and video. As Ndalianis says, “distinct media cross over into other media”--one fandom is crossed with another. Merging one universe with another, fans break the frame of two canons and see how they might combine, and characters from separate fandoms meet (“Crossover”).

Another way of breaking frames is in a more spatial, geographical way. Matt Hills discusses the experience of fans who visit the real physical setting of a canon--so-called “fan tourism”. This can take the form of visiting filming locations or places that appear in the story. For example, Hills discusses X-Files fans who visit certain neighborhoods in Vancouver because the show was filmed there. When I went to London I visited St. Paul’s Cathedral largely because it’s important to one of my favorite books, and I went to both the actual 221B Baker Street and the street where 221B was filmed for the BBC’s Sherlock. What Hills identifies as an important part of fan tourism is that these locations are not normal tourist locations--in general, one does not buy souvenirs or trip over other tourists--so the experience of the space can mirror the characters’ imagined experience of the space. Being in an imagined space breaks the frame by locating fictional spaces in the real world, making them real, with the potential to disappoint.

By seeking out the actual locations which underpin any given textual identity, the cult fan is able to extend the productivity of his or her affective relationship with the original text, reinscribing this attachment within a different domain (that of physical space) which in turn allows for a radically different object-relationship in terms of immediacy, embodiment, and somatic sensation which can all operate to reinforce cult ‘authenticity’ and its more-or-less explicitly sacralised difference. The audience-text relationship is shifted towards the monumentality and groundedness of physical locations. (Hills 149)

Visiting a fandom location allows the fan to enter into diegetic space in, as Hills says, an embodied way, which is very different from inhabiting the fandom’s world by writing about it. It also brings the diegetic world into the fan’s own world. This idea of fan tourism also harks back to Ndalianis’s idea of the baroque world as the “world as theatre” (15). For fans, media takes place in a visitable world, not simply on a screen.

Yet another breaking of the frame occurs when attention is drawn away from the internal world of the media and towards the form or technology of the media. In creating fan works, fans pick apart a text and put it back together again. In order to dabble in the world of the source material, it is necessary to know what makes that world tick. You have to establish the rules in order to break them. This process makes the content of a text an ongoing debate. "(Neo-)baroque form relies on the active engagement of audience members, who are invited to participate in a self-reflexive game involving the work's artifice" (Ndalianis 25). The neo-baroque draws attention to the form, the technology, the “artifice” of the media. Fans, when they examine a text for clues to how they might expand and play with that text, are looking at the form of the text separately from its content. Because a fan writer uses the same form (fiction) as that of the original text to critique or expand that text, they are looking at both the narrative and the narrative form, and exposing, in neo-baroque fashion, the “artifice” of fiction.

Technology and the Economics of Fandom

Ndalianis identifies both the seventeenth-century baroque and the twentieth-century neo-baroque with technological innovation. The seventeenth century marked the emergence of the idea of the machine, both in a literal sense and as a way to think about science (172). Generally speaking, the seventeenth century saw the scientific revolution. The twentieth century saw advancements notably in media, as more and more technological possibilities developed for television and film. Now in the twenty-first century, we have the Internet. The Internet has marked changes in the way we share information, interact with people, and interact with media. The Internet has had particular importance for changes in fan culture. It is no secret, of course, that the Internet has expanded the popularity, accessibility, and possibilities of fandom. In Digital Fandom, Paul Booth examines some of the changes made possible by the Internet, as well as the way fandom forces us to think about the Internet in different ways. He sees the Internet as a “Web Commons.”

Fans make use of the communal, social, and communicative properties of the web to form social grouping that relies on camaraderie and sharing. In this way, it is akin to the traditional conception of the feudal commons area. The Web Commons contrasts with the web as a resource for information, or what I’m calling the “Information Web.” (23)

Booth conceptualizes the “Information Web” as “like a vast library of books, hypertextually linked to one another” (ibid.). The Information Web model fails to take into account the enormous interactivity of the Internet. A library’s contents are accessible, but not interactive in the way the Internet is. New content is not constantly appearing in a library, generated by the library’s users, and so the Information Web model is insufficient. While it was always possible for fans to create new content for their fandom, before the Internet it was not possible to engage in the the kind of mass social sharing Booth mentions. With this sharing has come the enormously expanded multiplicity and interactivity that makes fandom so neo-baroque.

The Web Commons has affected not only the distribution of fan-created material, but the distribution of the source material as well. Before the invention of VCRs, DVDs, and, most importantly, the Internet, if a fan didn’t sit down in front of the television at the scheduled time, they missed the next episode of their favorite television show, and there was no way to see it after the fact. Likewise, there was no way to watch the show over again unless a rerun was aired. As Booth discusses, this meant that media functioned on a system of production and consumption. Once you had seen a particular episode, you had literally consumed it--it was, functionally speaking, gone for good. With the Internet, it is now possible to have the cake and eat it too. The consumption model no longer applies to the way we interact with media (Booth 41). Instead, it is possible to repeat the experience of a television show or film an infinite number of times, and in a very neo-baroque way the experience forms layers, repetitions which change in some way as the viewer notices or focuses on different things. Additionally, the structure of fandom and the Web Commons emphasizes community and sharing in a way that means access to the media is distributed in a network of people and a multiplicity of ways. This means that in a post-Internet world, the economy of media has changed profoundly. Instead of controlled, linear distribution which focuses on a production-consumption model, for fans media (both canon and fan-created) now works on a very different economy.

This change in the media economy is only the latest in a history of other economic changes which Ndalianis ties to the baroque. The development of both the baroque and the neo-baroque coincided with shifts in economic forms and the way media was distributed.

The burgeoning print industry recognized the economic possibilities of consumerism on a mass scale, and as the dissemination of plays, novels, biblical texts, and printed books, as well as other media such as the theater, opera, and mass-produced paintings, proliferated, a nascent popular culture emerged, one that was accompanied by a new fascination with the serial and the copy. (Ndalianis 26)

Similarly, neo-baroque media coincided with the development of conglomerates, so that multiple companies producing multiple media were owned by one conglomerate, thus encouraging polycentrism and interrelated media universes (ibid.). The Internet and its close relationship with fandom marks another shift in economic models. The Internet has not only taken the possibilities of mass media distribution far beyond its seventeenth-century roots, it has taken some of the power away from conglomerates, giving fans distribution abilities (if not distribution rights). Beyond the way the Internet has changed the distribution of canon media, it has also created (or re-discovered) a completely different economy for the distribution of fan media.

The Web Commons as a whole functions on what Booth calls the “Digi-Gratis Economy.”

The term Digi-Gratis indicates an economic structure where money is not exchanged, but which retains elements of a market structure. In a “gratis” economy, people create and share content without charge or recompense, or, at least, by charging a variable, user-determined fee. In many ways, this exchange is related to the gift economy described by Mauss as one where “exchanges and contracts take place in the form of presents...” The gift economy builds social bonds. (24)

This kind of economy involves no monetary exchange, but does require reciprocation in order to function. This is the economy of fandom. Fandom does not exist unless multiple people produce fan works and exchange them. This model is integral to fandom, and a major part of what makes fandom so neo-baroque. This economy is also largely foreign to the mainstream, and is the source of much confusion about fandom. Money and ownership in general is a major source of conflict and debate about fandom, both for fans and for the authors or owners of the source materials.

A common question levelled against fans is the issue of whether writing (or doing art or making music) is “work” and whether it is rational to do that “work” for no pay. One professional author who also writes fan fiction says, “Fanfic writing isn't work, it's joyful play. The problem is that for most people, any kind of writing looks like work to them, so they get confused why anyone would want to write fanfic instead of original professional material, even though they don't have any problem understanding why someone would want to mess around on a guitar playing Simon and Garfunkel" (qtd. in Grossman). It’s true that fan writing is play, but it does also require work. I would argue, not that fans aren’t doing “work”, but that they exist in the Digi-Gratis Economy and therefore do the work for reciprocity rather than money. It is the lack of understanding of the presence of a different economic system that prompts people to see fan work as pointless and crazy.

Mad Fandom

Ndalianis says that “for the eighteenth and, in particular, the nineteenth century, the baroque was increasingly understood as possessing traits that were unusual, vulgar, exuberant, and beyond the norm” (7). Like the baroque, fandom is seen as unusual and abnormal, potentially dangerous and irrational. Fans and fandom are subject to some very specific unfavorable stereotypes. Harrington and Bielby discuss the “General consensus … over the dominant stereotype of fandom--the all-too-familiar (to Western scholars at least) loser/lunatic image” (187). A recent issue of The Seattle Times featured the headline “FAN FRENZY GREETS STARS AT U-VILLAGE”, and said, “Fans go crazy Saturday as they finally get to see the movie stars they’ve been waiting for” (emphasis added). This is a familiar theme in fan studies. Cornel Sandvoss begins his book, Fans, with several paragraphs listing the multiple media images of fans as violent, such as the Eminem song “Stan” and the 1996 film The Fan, as well as assassinations and acts of violence attributed by the media to the perpetrators’ being fans, like John Lennon’s assassination and Columbine.

The origin of the word “fan” in “fanatic” is telling, and it further ties fandom to the baroque. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines a fanatic as “a person filled with excessive and mistaken enthusiasm”, which is reminiscent of the excess and exuberance of the baroque. However, “fanatic” began in the mid-sixteenth century as a “frenzied, mad” person, “such as might result from possession by a god or demon.” The association between fans and madness is long-lived. The relevance of the etymology of “fan” can be seen in Harrison and Bielby’s survey of fan scholars from around the world. One participant reported that, “[I]n Finland we do not have such prejudices concerning fans as ‘freaks’ as in the U.S. This may partly boil down to language: in Finnish the term ‘fani’ (fan) does not associate with ‘fanatic’ nearly as closely as in English” (Harrison and Bielby 187). This makes clear the importance of the connotations and history of the term “fan” for how we think about and represent fans. Given the connotations of madness in the word “fan”, it might seem logical for fans to choose a different way of identifying themselves. On the contrary, fans claim the word as an identity (Sandvoss 6) especially those who participate in fandom. In some way, fans claim their madness.

Fan scholars have different ways of dealing with the overwhelming view that fans are crazy. One common theme in fan studies is the idea that “everyone is a fan”. If fans are crazy and everyone is a fan, then everyone is crazy, which isn’t possible. Moving away from the study of science fiction fans or fans of “cult television,” scholars choose to study fans of sports, classical music, or “high culture” (Gray, Sandvoss, & Harrington). The idea, of course, is that the object of the fandom has some effect on the legitimacy of the fandom or the sanity of the fans. Fans of Shakespeare aren’t obsessive crazies; they’re educated theatre-goers. On the other hand, while everyone may be a fan of something, not everyone participates in a fandom as I have here defined it, and there is every chance that the authors of the 1,924 stories based on Shakespeare’s plays listed on FanFiction.Net would still be seen as crazy. The object of someone’s fandom is obviously important, but more important is what that person does as a fan.

Fandom occupies a lot of uncomfortable grey area. Fans use texts owned and authored by other people in unauthorized ways, and that inevitably brings up questions of stealing and intellectual property. Though some authors have threatened to take legal action against fans (Grossman), there is very little precedent in U.S. law to determine whether they have grounds to do so, and there is some reasonable basis for treating fan fiction as “fair use” because it is “transformative” (Tushnet 61). However, the dubious legality of fan works is one obvious place to locate the crazy fan image. Leaving aside legalities, the idea of fan work as unpaid and pointless that I have discussed is another place to locate madness in what fans do.

What fans do, as I have argued, is a profoundly neo-baroque endeavor. Creating a multiplicity of stories using the “aesthetics of repetition”, and breaking the limits of the frame, made possible by the technology of the Internet and the Digi-Gratis fan economy, fans do something which seems chaotic, labyrinthine, excessive, and economically irrational or dangerous. Most of what fans do that seems mad is made possible by the neo-baroque structure of the Web Commons, the Digi-Gratis economy, and fandom. The relationship between the “excessive enthusiasm” of fans and the excessive exuberance of the baroque shows a clear tie between the ways fans are seen as mad and the way the baroque is seen as mad. Though sports and music fans are also commonly seen as crazy, the specifics of the mad things people in Internet fandom do are all tied to the neo-baroque structure of those fandoms.

As the Internet becomes the most common way of interacting with the media, will the Web Commons model become so ubiquitous that fans’ way of responding to media becomes more normal? Will fans cease to be seen as mad?

Newsweek’s April 3, 2006, issue (Levy & Stone 2006: 45-53) has a cover story on “Putting the ‘We’ in Web,” which describes the convergence of factors that is leading to the success of a range of significant new companies, including Flickr, MySpace, Drabble, YouTube, Craigslist, eBay, del.icio.us, and Facebook, among others. Each of these companies is reaching critical mass by “harnessing collective intelligence,” supporting User-Generated Content, and creating a new “architecture of participation,” … (Jenkins 357).

If active audience participation and the serialization of audience knowledge becomes the norm, maybe these neo-baroque structures will come to seem less crazy, or maybe, even as they become normal, they will continue to appear so chaotic and uncontrollable that they will never be valued in the way linear, “reasonable” media is. Henry Jenkins argues that “fandom represents the experimental prototype, the testing ground for the way media and culture industries are going to operate in the future” (361). He argues that “We should no longer be talking about fans as if they were somehow marginal to the way the culture industries operate” (362). Still, the framing of fans as crazy clearly has not disappeared, if just recently the Seattle Times was talking about fans going crazy in a fan frenzy. If the neo-baroque way fans interact with media is increasingly moving into the mainstream, it is obviously not the only place to locate the madness of fandom. Still, I would argue that it has been a major part of fans’ madness in the past, and that it continues to be so. I would argue that the madness of fandom is intimately tied to the history of neo-baroque aesthetics and the apparent insanity of those aesthetics. I would also argue that there is value in participating in a mad endeavor such as fandom, specifically because that endeavor is mad.

Though the “everyone is a fan” argument might be an easy way to justify the study of specific fans, especially the “crazy” ones, it also takes a normalizing stance towards fandom. It suggests that what fans do is something everyone does, when in reality there is a great deal of variety in the ways to be a fan, especially as we extend our research to things like sports and music. When focusing on Internet media fandom, the “everyone is a fan” method of justifying fan studies ceases to be useful. A more useful way of justifying the value of fandom is to show, as I have done in this paper, that fandom has a different economy and different activities from more mainstream media interaction, and that its neo-baroque structure makes it, in some sense, mad. Even given the growing similarities between what fans do and what more mainstream corners of the Internet like Facebook and YouTube do, fandom continues to raise different questions. Websites like Facebook which intend the audience to interact with them don’t raise the kinds of issues fandom does, where fans interact with media in ways the authors or owners of that media hadn’t expected. By focusing on the madness of fandom, we can look at participation in fandom as a way to raise questions about media and follow a different logic.

As Ndalianis discusses, “Until the twentieth century, seventeenth-century baroque art was largely ignored by art historians" (Ndalianis 8). Part of the reason for this oversight seems to be that the baroque was considered too chaotic to be studied in a systematic way. What Ndalianis argues, and what I argue here, is that the (neo-)baroque has its own logic and its own order, which, while differing from classical reason and order, is nonetheless systematic. What the baroque offers us is a way to think according to a different logic, and thus to rethink logic itself, divorcing it from linear, “reasonable” forms of thought. Thinking with an alternative logic is a powerful way to examine knowledge, and I would argue that the most accessible way to enter into a baroque logic is to participate in fandom. Even while the Web Commons becomes a more familiar way to interact with media, fandom retains many multiple, serial, transgressive media responses which cannot be found elsewhere. Fandom also retains its long-held history as a mad thing to do, and becoming mad for a while continues to be a way to look at the world differently in a productive way. As fans and as fan scholars, our mission should be, not to normalize fandom as something everyone does, but to claim our madness as an important part of fandom.

Notes

Bibliography

"Alternate Universe." Fanlore. Organization for Transformative Works, 8 Feb. 2012. Web. 3 Mar. 2012.

Booth, Paul. Digital Fandom: New Media Studies. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2010. Print.

"Crossover." Fanlore. Organization for Transformative Works, 26 Feb. 2012. Web. 3 Mar. 2012.

"FAN FRENZY GREETS STARS AT U-VILLAGE." Seattle Times 11 Mar 2012: B2. Print.

Gray, Jonathan, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington, eds. Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. New York: New York University Press, 2007. Print.

Grossman, Lev. "The Boy Who Lived Forever." Time 7 Jul. 2011. Web.

Harrington, C. Lee, and Denise D. Bielby. "Global Fandom/Global Fan Studies." Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 179-197.

Harris, Cheryl, and Alison Alexander, eds. Theorizing Fandom: Fans, Subculture and Identity. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 1998. Print.

Hills, Matt. Fan Cultures. London: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Jenkins, Henry. “Afterword: The Future of Fandom.” Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 357-364.

"Lie Low at Lupin’s." Fanlore. Organization for Transformative Works, 5 Oct. 2011. Web. 2 Mar. 2012.

Ndalianis, Angela. Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005. Print.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. New York: Scholastic Press, 2000. Print.

Sandvoss, Cornel. Fans. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005. Print.

Tushnet, Rebecca. “Copyright Law, Fan Practices, and the Rights of the Author.” Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 60-71.

Genre: Meta

Word count: 6,200 (Long meta is long)

Rating: G

Warnings: None

Summary: In Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment, Angela Ndalianis shows how current media, particularly science fiction film franchises, reflect the aesthetics of the seventeenth-century baroque. Using Ndalianis’s definitions of the neo-baroque, I will show that if media is neo-baroque, fandom is even more so. I argue that there is a connection between the prevailing view of the baroque as chaotic, excessive, and unreasonable, and the prevailing view of fans as crazy--fandom is viewed as crazy largely because it is neo-baroque, and the neo-baroque nature of that craziness makes the madness of fandom a productive madness. Fan scholars, however, seem to feel the need to justify the study of fandom by normalizing fandom, and saying that “everyone is a fan.” On the contrary, what we should be doing is accepting that fandom is mad, and re-conceptualizing that madness as an alternative way to think and respond to media. Fandom challenges dominant ideas of reason, storytelling, authorship, and economics, and learning to respond to media through fandom--learning to enter into the madness of fandom--provides a means to think in different ways.

-

First, a few words about the context of this essay. It was written for a university class about madness and the politics of knowledge, which largely explored the ways madness can alternatively be seen as a failure to communicate in “normal” ways. We talked about Michel Foucualt’s theories of psychiatric power, various works about bipolar disorder and autism, the interrelation between psychology and the body, emotion vs. reason, psychotropic drugs, and (most relevant for this essay) the aesthetics of seventeenth-century baroque art. I think knowing that this was written within the context of an ongoing discussion about madness is fairly important for understanding why I wrote this the way I did. I’ve made some edits, since I don’t need to explain fandom to an audience of fans. However, it seems necessary to the arguments to leave a lot of this as it is, so if some of my examples seem obvious to you, it’s because they seem equally obvious to me from my position as a fan. I explain things the way I do because it’s useful to make explicit the relationship I see between fandom and the neo-baroque, and because this was not originally written for an audience of fans.

In Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment, Angela Ndalianis shows how current media, particularly science fiction film franchises, reflect the aesthetics of the seventeenth-century baroque. Using Ndalianis’s definitions of the neo-baroque, I will show that if media is neo-baroque, the fan responses to it are even more so. Fan culture is, in structure and practice, profoundly neo-baroque. I argue that there is a connection between the prevailing view of the baroque as chaotic, excessive, and unreasonable, and the prevailing view of fans as crazy--fandom is viewed as crazy largely because it is neo-baroque, and the neo-baroque nature of that craziness makes the madness of fandom a productive madness. Fan scholars, however, seem to feel the need to justify the study of fandom by normalizing fandom, and saying that “everyone is a fan.” On the contrary, what we should be doing is accepting that fandom is mad, and re-conceptualizing that madness as an alternative way to think and respond to media. Fandom challenges dominant ideas of reason, storytelling, authorship, and economics, and learning to respond to media through fandom--learning to enter into the madness of fandom--provides a means to think in different ways.

Since I can’t assume you’ve read my source material, as I did in the original paper, I’m going to give a brief tour of Angela Ndalianis’s book, Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment, and also talk a bit about baroque art. If you’re interested in reading Ndalianis, I have PDFs of the introduction and chapter one, and chapters four and five, so just drop me a line and I’ll send them along.

The baroque is a period in art--including sculpture, theatre, music, architecture, painting, literature and dance--situated roughly in the seventeenth century, in between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. It’s characterized by extravagance, excessiveness, repetition, extension or breaking of the frame, activity, and variation. One illustrative example of baroque art Ndalianis uses is the difference between Michelangelo’s statue of David (1504) and Bernini’s statue of David (1624). Whereas Michelangelo’s David only has a couple of obvious viewpoints (back, front, one side), with Bernini’s David there is no obvious point of view, no side from which you can see everything going on. Michelangelo’s David is not in motion, whereas Bernini’s David is. Because Bernini’s statue is in motion, and because the viewer has to walk around to see all of it, it interacts with the viewer in a way Michelangelo’s statue does not. Interacting with the audience is another key feature of the baroque.

Another of Ndalianis’s examples of baroque art is the ceiling of the Church of St. Ignazio in Rome, painted by Andrea Pozzo between 1685 and 1694. Because of the perspective in which the ceiling is painted, if you look at it from the right angle it looks as though there is a vaulted ceiling which extends up to heaven. In fact the ceiling is flat, but the real architecture of the church flows naturally into painted architecture. If you look at the ceiling from different angles, however, the perspective looks wrong and jarring. This isn’t a flaw, but a way to point out the illusion, and to bring to light the questionable nature of reality. The painted ceiling breaks through the framework of real physical architecture. The ceiling also relies on interaction with the viewer, because it matters where the viewer stands when they look at the ceiling.

Particularly important to the relationship between fandom and the baroque is the fact that baroque art has a long history of being devalued.

Although when the term "baroque" was originally applied to define the art and music of the seventeenth century is not known, its application in this way--and denigratory associations--gathered force during the eighteenth century. During this time, "baroque" implied an art or music of extravagance, impetuousness, and virtuosity, all of which were concerned with stirring the affections and senses of the individual. The baroque was believed to lack the reason and discipline that came to be associated with neoclassicism and the era of the Enlightenment.... (Ndalianis 7)

Wikipedia’s article about the baroque notes that in modern usage “baroque” is usually applied pejoratively. Baroque art was not considered worthy of study in art history for a very long time. Modern media which follows baroque aesthetics has a similar tendency to be devalued, as you know if you’ve spent any time trying to justify your participation in fandom, or if you look at the way the science fiction universes Ndalianis discusses are generally not taken very seriously.

Ndalianis shows that “particular features of a baroque poetics emerged:

minimal or lack of concern with plot development and a preference for a multiple and fragmented structure that recalls the form of a labyrinth; open rather than closed form; a complexity and layering evident, for example, in the merging of genres and literary forms such as poetry and the novel …. a view of the illusory nature of the world--a world as theatre, a virtuosity revealed through stylistic flourish and allusion; and a self-reflexivity that requires active audience engagement. (15)

Ndalianis identifies contemporary media as baroque through many different examples. One of these is the world of Batman, which exists in several different comic books, crossovers with other comic book universes, multiple movies over several decades, television series, and video games (34). The Batman universe exists in multiple media and multiple retellings of the same story, and has existed since the 1930’s. People keep retelling it because the characters continue to be interesting and different people want to continue to make their own interpretation of them. New Batman films, comics, or games are variations on a theme--a feature characteristic of baroque music (see the embedded video below). Other science fiction universes, such as Star Wars, Jurassic Park, and Alien, are structured similarly. These universes are complex, but the body of material created by fans about any of them is even more so. To me, fandom is so relevant and clear an example of the neo-baroque that I felt it was a blatant omission from Ndalianis’s work.

Neo-Baroque Fandom

“Fandom” in the context of this paper is meant to connote fan culture and communities, not the state of being a fan--more along the lines of “kingdom” than “stardom”. Any given fandom is the community centered around a particular originating text, whether that text is a single book or a collection of multiple stories within a single universe. The work of fandom is to interpret its text--its canon--and to spell out its interpretations, not (as literary theory spells out interpretations) in an essay, but in the same form as the original--in a story. Fans interpret the characters, the plots, and the world of their source material, and they tell the stories that result out of these interpretations through fiction, art, music, and film. In the Ndalianis passage quoted above, “active audience engagement” is listed as one of the main features of the baroque. Fan work is perhaps the most active engagement possible for an audience.

According to one participant in a survey of fan studies scholars, what distinguishes a fan of a text from a consumer of a text is that the fan “develops a personal attachment to a particular media artifact or ‘star’ and actively engages in a multiplicity of levels of creation that transcends or could even transform the ‘original’ text, character, or star persona” (Harrington and Bielby 186). Multiplicity is an important feature of the baroque. What makes fandom even more multiple than media universes like Batman is the fact that the creations of fandom are not required to be coherent. That is, an infinite number of stories can be told because they are not required to agree with any previous stories, or even completely with the canon. Internal consistency may or may not be a concern of retellings of the Batman story, but it is generally important that a retelling or a sequel not completely change something that was established in a previous story. In fandom, no such rule applies.

Fan authors are often explicit about their relationship to the real, canonical texts: the fan creations lack the authority of official texts. Because they are not canonical, fan stories can offer a thousand different ways that Mulder and Scully first slept together, none of which contradict the others, or one author can write “Five Things That Never Happened”--five alternate histories for a favorite character, all of which are, as the title states, repudiated by the author (Because AUs Make Us Happy n.d.). Lack of authority, which stems from lack of authorization, allows a freedom unavailable to an official canon striving for internal consistency. (Tushnet 67)

Thus, fandom has far more freedom in its multiplicity than the canonical, authorized texts do.

Another key feature of the neo-baroque is its seriality.

The use of multiple narrative centers (multiple originals) typical of seriality requires a reconsideration of traditional perceptions of linearity and closed narrative form. Neo-baroque seriality demands that a single linear framework no longer dominate the whole. Operating on the impetus of a repetitive drive, the baroque work produces "an aesthetic of repetition," and it is precisely this aesthetic of repetition that underlies the logic of the serial whole and its relationship to the fragment. (Ndalianis 69)

The multiplicity of fandom is the perfect environment for this “aesthetics of repetition” and seriality. Commonly, there will be moments in canon--lines of dialogue, events referenced but not shown, and so on--which prompt multiple fan writers to interpret those possible stories in their own way, regardless of the number of people who have already done so. One example is a line in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, when Dumbledore tells Sirius Black to “lie low at Lupin’s for a while” (Rowling 713). This created an entire genre of Harry Potter fan fiction, in which stories detail the time Sirius spends “lying low at Lupin’s” (Grossman). Though these stories all follow the same premise and roughly the same plot, the many possible interpretations of the characters allow for many retellings.

Fandom breaks boundaries, whether between diegetic and audience space, between author and reader, or between narratives.

The central characteristic of the baroque that informs this study is this lack of respect for the limits of the frame. Closed forms are replaced by open structures that favor a dynamic and expanding polycentrism. Stories refuse to be contained within a single structure, expanding their narrative universes into further sequels and serials. Distinct media cross over into other media, merging with, influencing, or being influenced by other media forms. (Ndalianis 25)

A common feature of fandom is this tendency to ignore the frame. As long as characters remain recognizable, there are no limits to what setting they can be placed in. Alternate Universe (AU) fan fiction is one way of expanding or moving the frame. An AU story might be one of several things. It might change one event in the original canon and explore how later events would go differently under those circumstances, it might transplant the characters into a different environment (a different part of history, for example), or it might change a particular feature of the characters (gender, occupation, etc.) (“Alternate Universe”). Another way of breaking the frame is crossover fan fiction, art, and video. As Ndalianis says, “distinct media cross over into other media”--one fandom is crossed with another. Merging one universe with another, fans break the frame of two canons and see how they might combine, and characters from separate fandoms meet (“Crossover”).

Another way of breaking frames is in a more spatial, geographical way. Matt Hills discusses the experience of fans who visit the real physical setting of a canon--so-called “fan tourism”. This can take the form of visiting filming locations or places that appear in the story. For example, Hills discusses X-Files fans who visit certain neighborhoods in Vancouver because the show was filmed there. When I went to London I visited St. Paul’s Cathedral largely because it’s important to one of my favorite books, and I went to both the actual 221B Baker Street and the street where 221B was filmed for the BBC’s Sherlock. What Hills identifies as an important part of fan tourism is that these locations are not normal tourist locations--in general, one does not buy souvenirs or trip over other tourists--so the experience of the space can mirror the characters’ imagined experience of the space. Being in an imagined space breaks the frame by locating fictional spaces in the real world, making them real, with the potential to disappoint.

By seeking out the actual locations which underpin any given textual identity, the cult fan is able to extend the productivity of his or her affective relationship with the original text, reinscribing this attachment within a different domain (that of physical space) which in turn allows for a radically different object-relationship in terms of immediacy, embodiment, and somatic sensation which can all operate to reinforce cult ‘authenticity’ and its more-or-less explicitly sacralised difference. The audience-text relationship is shifted towards the monumentality and groundedness of physical locations. (Hills 149)

Visiting a fandom location allows the fan to enter into diegetic space in, as Hills says, an embodied way, which is very different from inhabiting the fandom’s world by writing about it. It also brings the diegetic world into the fan’s own world. This idea of fan tourism also harks back to Ndalianis’s idea of the baroque world as the “world as theatre” (15). For fans, media takes place in a visitable world, not simply on a screen.

Yet another breaking of the frame occurs when attention is drawn away from the internal world of the media and towards the form or technology of the media. In creating fan works, fans pick apart a text and put it back together again. In order to dabble in the world of the source material, it is necessary to know what makes that world tick. You have to establish the rules in order to break them. This process makes the content of a text an ongoing debate. "(Neo-)baroque form relies on the active engagement of audience members, who are invited to participate in a self-reflexive game involving the work's artifice" (Ndalianis 25). The neo-baroque draws attention to the form, the technology, the “artifice” of the media. Fans, when they examine a text for clues to how they might expand and play with that text, are looking at the form of the text separately from its content. Because a fan writer uses the same form (fiction) as that of the original text to critique or expand that text, they are looking at both the narrative and the narrative form, and exposing, in neo-baroque fashion, the “artifice” of fiction.

Technology and the Economics of Fandom

Ndalianis identifies both the seventeenth-century baroque and the twentieth-century neo-baroque with technological innovation. The seventeenth century marked the emergence of the idea of the machine, both in a literal sense and as a way to think about science (172). Generally speaking, the seventeenth century saw the scientific revolution. The twentieth century saw advancements notably in media, as more and more technological possibilities developed for television and film. Now in the twenty-first century, we have the Internet. The Internet has marked changes in the way we share information, interact with people, and interact with media. The Internet has had particular importance for changes in fan culture. It is no secret, of course, that the Internet has expanded the popularity, accessibility, and possibilities of fandom. In Digital Fandom, Paul Booth examines some of the changes made possible by the Internet, as well as the way fandom forces us to think about the Internet in different ways. He sees the Internet as a “Web Commons.”

Fans make use of the communal, social, and communicative properties of the web to form social grouping that relies on camaraderie and sharing. In this way, it is akin to the traditional conception of the feudal commons area. The Web Commons contrasts with the web as a resource for information, or what I’m calling the “Information Web.” (23)

Booth conceptualizes the “Information Web” as “like a vast library of books, hypertextually linked to one another” (ibid.). The Information Web model fails to take into account the enormous interactivity of the Internet. A library’s contents are accessible, but not interactive in the way the Internet is. New content is not constantly appearing in a library, generated by the library’s users, and so the Information Web model is insufficient. While it was always possible for fans to create new content for their fandom, before the Internet it was not possible to engage in the the kind of mass social sharing Booth mentions. With this sharing has come the enormously expanded multiplicity and interactivity that makes fandom so neo-baroque.

The Web Commons has affected not only the distribution of fan-created material, but the distribution of the source material as well. Before the invention of VCRs, DVDs, and, most importantly, the Internet, if a fan didn’t sit down in front of the television at the scheduled time, they missed the next episode of their favorite television show, and there was no way to see it after the fact. Likewise, there was no way to watch the show over again unless a rerun was aired. As Booth discusses, this meant that media functioned on a system of production and consumption. Once you had seen a particular episode, you had literally consumed it--it was, functionally speaking, gone for good. With the Internet, it is now possible to have the cake and eat it too. The consumption model no longer applies to the way we interact with media (Booth 41). Instead, it is possible to repeat the experience of a television show or film an infinite number of times, and in a very neo-baroque way the experience forms layers, repetitions which change in some way as the viewer notices or focuses on different things. Additionally, the structure of fandom and the Web Commons emphasizes community and sharing in a way that means access to the media is distributed in a network of people and a multiplicity of ways. This means that in a post-Internet world, the economy of media has changed profoundly. Instead of controlled, linear distribution which focuses on a production-consumption model, for fans media (both canon and fan-created) now works on a very different economy.

This change in the media economy is only the latest in a history of other economic changes which Ndalianis ties to the baroque. The development of both the baroque and the neo-baroque coincided with shifts in economic forms and the way media was distributed.

The burgeoning print industry recognized the economic possibilities of consumerism on a mass scale, and as the dissemination of plays, novels, biblical texts, and printed books, as well as other media such as the theater, opera, and mass-produced paintings, proliferated, a nascent popular culture emerged, one that was accompanied by a new fascination with the serial and the copy. (Ndalianis 26)

Similarly, neo-baroque media coincided with the development of conglomerates, so that multiple companies producing multiple media were owned by one conglomerate, thus encouraging polycentrism and interrelated media universes (ibid.). The Internet and its close relationship with fandom marks another shift in economic models. The Internet has not only taken the possibilities of mass media distribution far beyond its seventeenth-century roots, it has taken some of the power away from conglomerates, giving fans distribution abilities (if not distribution rights). Beyond the way the Internet has changed the distribution of canon media, it has also created (or re-discovered) a completely different economy for the distribution of fan media.

The Web Commons as a whole functions on what Booth calls the “Digi-Gratis Economy.”

The term Digi-Gratis indicates an economic structure where money is not exchanged, but which retains elements of a market structure. In a “gratis” economy, people create and share content without charge or recompense, or, at least, by charging a variable, user-determined fee. In many ways, this exchange is related to the gift economy described by Mauss as one where “exchanges and contracts take place in the form of presents...” The gift economy builds social bonds. (24)

This kind of economy involves no monetary exchange, but does require reciprocation in order to function. This is the economy of fandom. Fandom does not exist unless multiple people produce fan works and exchange them. This model is integral to fandom, and a major part of what makes fandom so neo-baroque. This economy is also largely foreign to the mainstream, and is the source of much confusion about fandom. Money and ownership in general is a major source of conflict and debate about fandom, both for fans and for the authors or owners of the source materials.

A common question levelled against fans is the issue of whether writing (or doing art or making music) is “work” and whether it is rational to do that “work” for no pay. One professional author who also writes fan fiction says, “Fanfic writing isn't work, it's joyful play. The problem is that for most people, any kind of writing looks like work to them, so they get confused why anyone would want to write fanfic instead of original professional material, even though they don't have any problem understanding why someone would want to mess around on a guitar playing Simon and Garfunkel" (qtd. in Grossman). It’s true that fan writing is play, but it does also require work. I would argue, not that fans aren’t doing “work”, but that they exist in the Digi-Gratis Economy and therefore do the work for reciprocity rather than money. It is the lack of understanding of the presence of a different economic system that prompts people to see fan work as pointless and crazy.

Mad Fandom

Ndalianis says that “for the eighteenth and, in particular, the nineteenth century, the baroque was increasingly understood as possessing traits that were unusual, vulgar, exuberant, and beyond the norm” (7). Like the baroque, fandom is seen as unusual and abnormal, potentially dangerous and irrational. Fans and fandom are subject to some very specific unfavorable stereotypes. Harrington and Bielby discuss the “General consensus … over the dominant stereotype of fandom--the all-too-familiar (to Western scholars at least) loser/lunatic image” (187). A recent issue of The Seattle Times featured the headline “FAN FRENZY GREETS STARS AT U-VILLAGE”, and said, “Fans go crazy Saturday as they finally get to see the movie stars they’ve been waiting for” (emphasis added). This is a familiar theme in fan studies. Cornel Sandvoss begins his book, Fans, with several paragraphs listing the multiple media images of fans as violent, such as the Eminem song “Stan” and the 1996 film The Fan, as well as assassinations and acts of violence attributed by the media to the perpetrators’ being fans, like John Lennon’s assassination and Columbine.

The origin of the word “fan” in “fanatic” is telling, and it further ties fandom to the baroque. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines a fanatic as “a person filled with excessive and mistaken enthusiasm”, which is reminiscent of the excess and exuberance of the baroque. However, “fanatic” began in the mid-sixteenth century as a “frenzied, mad” person, “such as might result from possession by a god or demon.” The association between fans and madness is long-lived. The relevance of the etymology of “fan” can be seen in Harrison and Bielby’s survey of fan scholars from around the world. One participant reported that, “[I]n Finland we do not have such prejudices concerning fans as ‘freaks’ as in the U.S. This may partly boil down to language: in Finnish the term ‘fani’ (fan) does not associate with ‘fanatic’ nearly as closely as in English” (Harrison and Bielby 187). This makes clear the importance of the connotations and history of the term “fan” for how we think about and represent fans. Given the connotations of madness in the word “fan”, it might seem logical for fans to choose a different way of identifying themselves. On the contrary, fans claim the word as an identity (Sandvoss 6) especially those who participate in fandom. In some way, fans claim their madness.

Fan scholars have different ways of dealing with the overwhelming view that fans are crazy. One common theme in fan studies is the idea that “everyone is a fan”. If fans are crazy and everyone is a fan, then everyone is crazy, which isn’t possible. Moving away from the study of science fiction fans or fans of “cult television,” scholars choose to study fans of sports, classical music, or “high culture” (Gray, Sandvoss, & Harrington). The idea, of course, is that the object of the fandom has some effect on the legitimacy of the fandom or the sanity of the fans. Fans of Shakespeare aren’t obsessive crazies; they’re educated theatre-goers. On the other hand, while everyone may be a fan of something, not everyone participates in a fandom as I have here defined it, and there is every chance that the authors of the 1,924 stories based on Shakespeare’s plays listed on FanFiction.Net would still be seen as crazy. The object of someone’s fandom is obviously important, but more important is what that person does as a fan.

Fandom occupies a lot of uncomfortable grey area. Fans use texts owned and authored by other people in unauthorized ways, and that inevitably brings up questions of stealing and intellectual property. Though some authors have threatened to take legal action against fans (Grossman), there is very little precedent in U.S. law to determine whether they have grounds to do so, and there is some reasonable basis for treating fan fiction as “fair use” because it is “transformative” (Tushnet 61). However, the dubious legality of fan works is one obvious place to locate the crazy fan image. Leaving aside legalities, the idea of fan work as unpaid and pointless that I have discussed is another place to locate madness in what fans do.

What fans do, as I have argued, is a profoundly neo-baroque endeavor. Creating a multiplicity of stories using the “aesthetics of repetition”, and breaking the limits of the frame, made possible by the technology of the Internet and the Digi-Gratis fan economy, fans do something which seems chaotic, labyrinthine, excessive, and economically irrational or dangerous. Most of what fans do that seems mad is made possible by the neo-baroque structure of the Web Commons, the Digi-Gratis economy, and fandom. The relationship between the “excessive enthusiasm” of fans and the excessive exuberance of the baroque shows a clear tie between the ways fans are seen as mad and the way the baroque is seen as mad. Though sports and music fans are also commonly seen as crazy, the specifics of the mad things people in Internet fandom do are all tied to the neo-baroque structure of those fandoms.

As the Internet becomes the most common way of interacting with the media, will the Web Commons model become so ubiquitous that fans’ way of responding to media becomes more normal? Will fans cease to be seen as mad?

Newsweek’s April 3, 2006, issue (Levy & Stone 2006: 45-53) has a cover story on “Putting the ‘We’ in Web,” which describes the convergence of factors that is leading to the success of a range of significant new companies, including Flickr, MySpace, Drabble, YouTube, Craigslist, eBay, del.icio.us, and Facebook, among others. Each of these companies is reaching critical mass by “harnessing collective intelligence,” supporting User-Generated Content, and creating a new “architecture of participation,” … (Jenkins 357).

If active audience participation and the serialization of audience knowledge becomes the norm, maybe these neo-baroque structures will come to seem less crazy, or maybe, even as they become normal, they will continue to appear so chaotic and uncontrollable that they will never be valued in the way linear, “reasonable” media is. Henry Jenkins argues that “fandom represents the experimental prototype, the testing ground for the way media and culture industries are going to operate in the future” (361). He argues that “We should no longer be talking about fans as if they were somehow marginal to the way the culture industries operate” (362). Still, the framing of fans as crazy clearly has not disappeared, if just recently the Seattle Times was talking about fans going crazy in a fan frenzy. If the neo-baroque way fans interact with media is increasingly moving into the mainstream, it is obviously not the only place to locate the madness of fandom. Still, I would argue that it has been a major part of fans’ madness in the past, and that it continues to be so. I would argue that the madness of fandom is intimately tied to the history of neo-baroque aesthetics and the apparent insanity of those aesthetics. I would also argue that there is value in participating in a mad endeavor such as fandom, specifically because that endeavor is mad.

Though the “everyone is a fan” argument might be an easy way to justify the study of specific fans, especially the “crazy” ones, it also takes a normalizing stance towards fandom. It suggests that what fans do is something everyone does, when in reality there is a great deal of variety in the ways to be a fan, especially as we extend our research to things like sports and music. When focusing on Internet media fandom, the “everyone is a fan” method of justifying fan studies ceases to be useful. A more useful way of justifying the value of fandom is to show, as I have done in this paper, that fandom has a different economy and different activities from more mainstream media interaction, and that its neo-baroque structure makes it, in some sense, mad. Even given the growing similarities between what fans do and what more mainstream corners of the Internet like Facebook and YouTube do, fandom continues to raise different questions. Websites like Facebook which intend the audience to interact with them don’t raise the kinds of issues fandom does, where fans interact with media in ways the authors or owners of that media hadn’t expected. By focusing on the madness of fandom, we can look at participation in fandom as a way to raise questions about media and follow a different logic.

As Ndalianis discusses, “Until the twentieth century, seventeenth-century baroque art was largely ignored by art historians" (Ndalianis 8). Part of the reason for this oversight seems to be that the baroque was considered too chaotic to be studied in a systematic way. What Ndalianis argues, and what I argue here, is that the (neo-)baroque has its own logic and its own order, which, while differing from classical reason and order, is nonetheless systematic. What the baroque offers us is a way to think according to a different logic, and thus to rethink logic itself, divorcing it from linear, “reasonable” forms of thought. Thinking with an alternative logic is a powerful way to examine knowledge, and I would argue that the most accessible way to enter into a baroque logic is to participate in fandom. Even while the Web Commons becomes a more familiar way to interact with media, fandom retains many multiple, serial, transgressive media responses which cannot be found elsewhere. Fandom also retains its long-held history as a mad thing to do, and becoming mad for a while continues to be a way to look at the world differently in a productive way. As fans and as fan scholars, our mission should be, not to normalize fandom as something everyone does, but to claim our madness as an important part of fandom.

Notes

- If you’ve spent any time studying women studies or the history of psychology, or, frankly, living as a woman, you know that historically women have often been associated with madness, emotionality, and inability to reason. There is something masculine about linear logic, especially as so many of the philosophers throughout history who established the value of that kind of reasoning were men. I think there’s something gendered about the devaluation of the baroque, with all its associations with labyrinthine structure and emotionality. I’d like to follow this into the assumption that everyone in fandom is a woman (or at least anything but a straight cis-man). I think there’s a relationship there, and I’d be interested in hearing people’s thoughts on that.

- When I started researching this, I was surprised by how much material has been published about fandom. I don’t think it’s common knowledge among fans that this work is being done. We’ve all seen that Henry Jenkin’s quote--“Fan fiction is a way of the culture repairing the damage done in a system where contemporary myths are owned by corporations instead of by the folk.”--but I don’t know anyone in fandom who’s read his books, such as Textual Poachers and Convergence Culture. I think it would be really useful to us to read some of it. I realize I’ve taken issue with a trend in fan studies in this paper, but reading these books seems like a good start for learning to more actively think about fandom, whether or not we agree with the way fan studies does things. A surprising amount of fan studies was done in the early 90’s, pre-Internet, so some of it is still relevant and some is hilariously dated. More recent stuff I would recommend is Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World, edited by Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington, and Paul Booth’s Digital Fandom: New Media Studies. I have no idea how easy these are to get hold of, since I have access to a university library, but I think if fandom were more aware of fan studies we would have more resources to understand and advocate for fandom.

Bibliography

"Alternate Universe." Fanlore. Organization for Transformative Works, 8 Feb. 2012. Web. 3 Mar. 2012.

Booth, Paul. Digital Fandom: New Media Studies. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2010. Print.

"Crossover." Fanlore. Organization for Transformative Works, 26 Feb. 2012. Web. 3 Mar. 2012.

"FAN FRENZY GREETS STARS AT U-VILLAGE." Seattle Times 11 Mar 2012: B2. Print.

Gray, Jonathan, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington, eds. Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. New York: New York University Press, 2007. Print.

Grossman, Lev. "The Boy Who Lived Forever." Time 7 Jul. 2011. Web.

Harrington, C. Lee, and Denise D. Bielby. "Global Fandom/Global Fan Studies." Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 179-197.

Harris, Cheryl, and Alison Alexander, eds. Theorizing Fandom: Fans, Subculture and Identity. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 1998. Print.

Hills, Matt. Fan Cultures. London: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Jenkins, Henry. “Afterword: The Future of Fandom.” Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 357-364.

"Lie Low at Lupin’s." Fanlore. Organization for Transformative Works, 5 Oct. 2011. Web. 2 Mar. 2012.

Ndalianis, Angela. Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005. Print.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. New York: Scholastic Press, 2000. Print.

Sandvoss, Cornel. Fans. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005. Print.

Tushnet, Rebecca. “Copyright Law, Fan Practices, and the Rights of the Author.” Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 60-71.