Избыточная смертность

(предыдущая страница)

Приложение 1

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56454701

Coronavirus: How Russia glosses over its Covid death toll

Protecting themselves for a shift on the Covid ward is a process the medics at Perm Regional Hospital have fine-tuned over months of practice. They climb quickly into disposable suits before strapping plastic masks tight to their faces. A colleague then helps them on with a double layer of rubber gloves, taped to their wrists.

A year into the pandemic, the virus this team are battling is familiar, but their careful daily routine is a reminder of the risk - it was last autumn that Covid-19 struck hardest in Perm, on its sweep from Moscow across the regions, and the number of sick and dead shot up.

But there is very little talk in Russia of the death toll from Covid. The full data revealed by excess mortality is not secret, but it's never highlighted, and the preliminary tally published each day by the government significantly underplays the impact.

The names and the numbers

Valery Gilyov fell sick in September with classic symptoms of Covid. A security guard at a Perm TV station, he began posting a diary on social media, describing calling for ambulances that never came.

In his last post before dying, Gilyov wrote that he was finally in hospital but felt "very bad".

Фото. Alongside Valery Gilyov's final diary entry he posted a selfie in an oxygen mask

image captionAlongside Valery Gilyov's final diary entry he posted a selfie in an oxygen mask

"I think he might have been saved," his son-in-law Viktor Morzhin tells me, remembering how Valery had loved taking his grandsons to taekwondo and hip-hop contests. "I think the health service, the authorities, just weren't ready for so many patients."

In that autumn surge of Covid infections, 2,388 people died of the virus in Perm according to the Rosstat state statistics agency. But the excess death data for Perm - the number of people dying above the expected norm - is double that figure for those four months, according to the same source.

Meanwhile, the city government count has only reached 1,869 for the whole of the pandemic.

Higher mortality in two Russian cities

Excess mortality in Moscow: 28,233

In 2020: 149,281; in 2019: 121,048

Excess mortality in Perm: 5,683

In 2020: 40,123; In 2019: 34,440

Source: Rosstat

The demographer's story

"I don't even look at those numbers," demographer Alexei Raksha says, and claims that the daily data in Russia has been "smoothed, rounded, lowered" to look better.

Officials have always denied that.

Alexei worked at Rosstat for six years until he says he was forced to leave last summer for being too vocal about Covid. But he says Rosstat's numbers are critical to assessing the real cost of the pandemic and, like many experts, he uses excess mortality as the best indicator.

Deaths in Russia in 2020.

"If Russia stops at 500,000 excess deaths, that will be a good scenario," the now freelance demographer argues. He calculates that the current toll is pushing 450,000 - a giant leap from the 94,267 deaths published online on Friday by Russia's Covid headquarters.

Even that lower number is rarely cited by officials, though.

"In Covid, you choose between the economy and people's lives - mostly older people's lives," is how Alexei sees the government's rationale. We met in a coffee bar - there's been no lockdown here since Spring.

"The Russian state chose the economy. They won't say it, but it's obvious."

Flats in Perm in the Urals

image caption The true number of Russian Covid fatalities is likely to come from excess deaths, equivalent in 2020 to almost a third of Perm's population of one million

Resisting lockdown

Most Covid restrictions were lifted nationwide in June, partly to allow a referendum that would enable Vladimir Putin to stay in power. In Perm, the healthcare system began feeling the fallout in autumn.

In early October, Artyom Boriskin posted a video online showing queues of ambulances.

An ambulance nurse, he remembers having to leave sick people at home because hospitals had no space for them. As ambulance crews caught Covid themselves, he says patients waited "from two to 20 hours" for a call-out, even several days.

"I think the measures taken weren't enough to reduce the number of new cases," Artyom argues. He believes the government resisted a second shutdown "because then it would have had to pay people" to stay at home.

"The restrictions should have been tougher. I think we'd have had fewer cases of illness and fewer deaths."

Herd immunity?

A few months on, there's little hint of spring on the frozen streets of Perm.

There's also minimal sign of the pandemic other than people in facemasks. Shops are open, buses are busy and the curfew for bars only kicks-in at 01:00.

But these days, the infection rate is low across Russia, perhaps because so many people have already had the virus. Alexei Raksha calculates up to a third of the population may have been infected, judging by the excess mortality data.

Perm Regional hospital hasn't stopped admitting Covid cases, though.

"We managed to stabilise this problem, but it hasn't gone anywhere," says chief doctor Anatoly Kasatov, standing beside a gold-painted statue of Lenin that now decorates a hospital corridor along with some pot plants.

But he doesn't agree that the government should have locked down tighter.

The decision is made by representatives from all official spheres, he notes, not only healthcare.

You can't leave people without work. Obviously, the best protection would be a spacesuit, but you can’t wear that for a whole year. So we look for a reasonable balance

Anatoly Kasatov Chief doctor, Perm Regional hospital

Hard history

Alexei Raksha suggests there's another reason Russians don't dwell on the dead like others - this country has experienced terrible turmoil in its recent past, with the collapse of the USSR.

"Europeans or Americans have not lived through bad times like the 90s in Russia," the demographer points out. "It was worse than the Great Depression in America. In comparison to those times, which Russians still remember, this Covid crisis is nothing."

It's not "nothing" for the tens of thousands of families directly affected, of course.

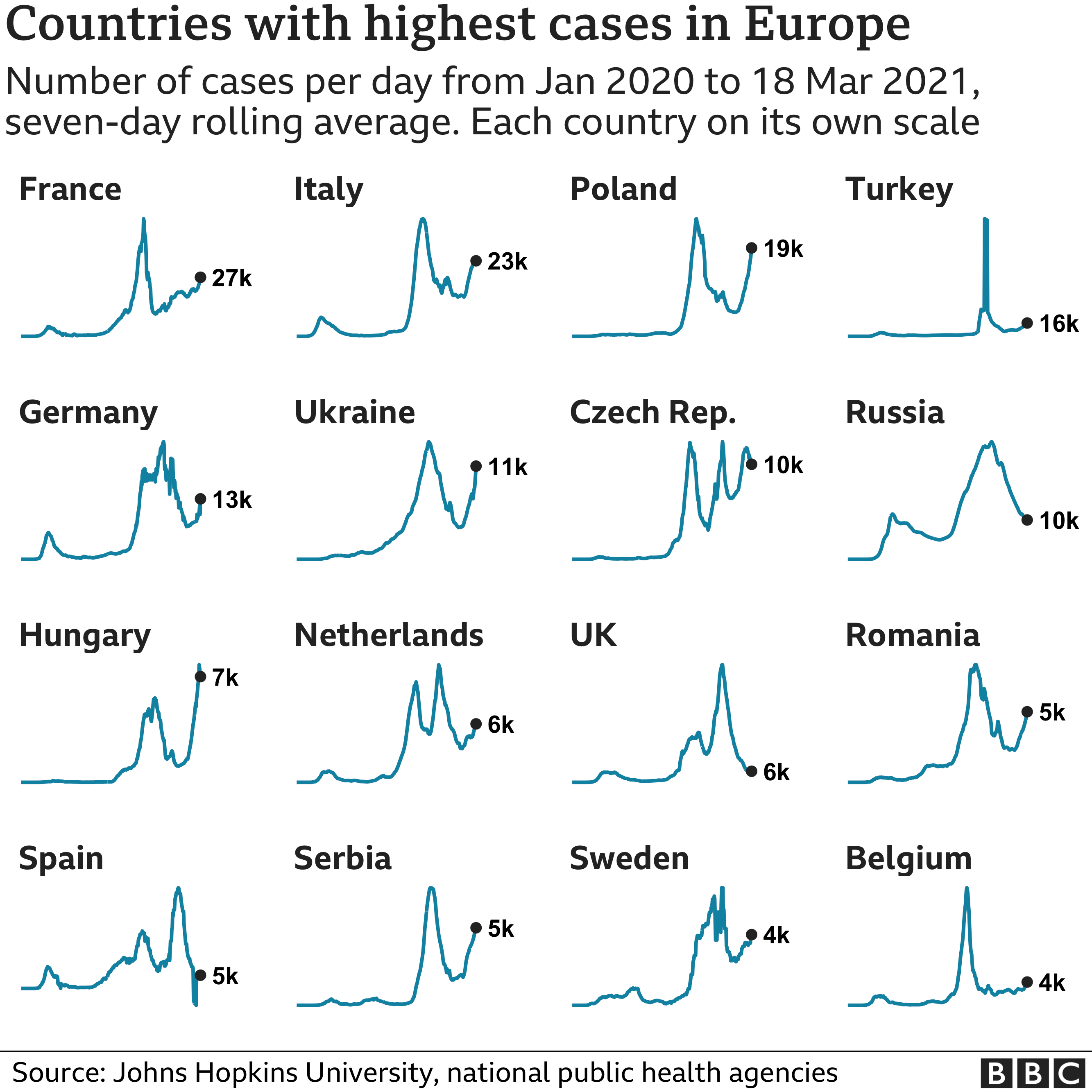

But Russia's official narrative, carried into living rooms via state TV, is that it's handled this pandemic better than most - that the country is on its way to recovery, just as Europe slides into another miserable cycle of restrictions.

The awkward numbers here are glossed over. The stories of the dead just don't get told.

(следующая страница)

Содержание