Chrono Trigger: An Existentialist Reading (Part I)

You know, when I sat down to write a series of articles about my Existentialist reading of Chrono Trigger, I initially started out with a bunch of explanatory text, background information and disclaimers. About a page into that mess, I decided that my efforts were futile. I am writing to an almost comically tiny audience with this series, and there's nothing I can do about it. Better to accept that and jump right in, I figure.

So for those of you who are in the know about Chrono Trigger and about Existentialism, here's the long and short: Although Chrono Trigger is by no means a heavyweight philosophical text, it has philosophical underpinnings and, more importantly, crafts a broad-ranging pastiche/satire of various pasts and futures as they are imagined in popular culture. As Umberto Eco writes of Casablanca, "the clichés are having a ball" in Chrono Trigger. What's more, the very format of the console RPG creates an experience that is well-suited to exploration of existential questions; Chrono Trigger, like other games of its ilk, presents the player with a complete world and asks him or her to make meaningful choices in that world -- and, yes, to kill some goblins along the way. It's not exactly Being and Nothingness, but it's not Pac-Man, either.

My plan is to play through Chrono Trigger yet again and to look at the statements and assumptions about existence that arise in the game, with special emphasis on Identity, Choice, Subjectivity/Objectivity, Time and Death. It's worth repeating explicitly that I'm not out to prove that complex philosophical statements were deliberately embedded in this video game. Instead, I'm trying to show that the format, the subject matter and the intertextual nature of Chrono Trigger make it possible to read the game as a negotiation of these subjects.

Enough of that. Let's get to the game.

Synopsis, Part One

Chrono Trigger opens with a pendulum swinging repeatedly past the screen, gradually losing energy and finally stopping fully in frame. The title then emerges alongside the pendulum. This image has special significance because, as we will learn much later at a key point in the game, a "Chrono Trigger" is a device that can literally stop time. This is not the usual method of time travel in the game, but a one-time occurrence that nevertheless gives the game its title and gives meaning to this title screen. It's enough for now to point it out and to remember that the very first image of this game, which seems superficially to be about the vast and unstoppable sweep of time, is that of a pendulum ceasing to swing.

Our introduction to Crono and his world is extremely straightforward for a console RPG. We get a moving overhead shot of Crono's town, followed by the ringing of a bell and Crono's Mom opening his bedroom window (cf. Psycho). Crono's Mom identifies the ringing as Leene's Bell; more on that later. We discover from Crono's Mom that the Millennial Fair is beginning today, and that Crono is supposed to meet his inventor friend Lucca there. With that simple introduction, we're out of Crono's house and into the main body of the game.

When Crono visits the Millennial Fair, he bumps into a girl in front of Leene's Bell, knocking her over and causing her to drop her pendant. Predictably, the bell rings. As we learn at the Fair, the bell is said to guarantee a happy and interesting life to those who hear it ring. Crono returns the pendant to the girl. She introduces herself as Marle (after some hesitation about her name) and asks to join Crono. He accepts.

After some hijinks at the fair, the two go to see Lucca's exhibition of her new invention, a "telepod" that can teleport people over a short distance. Crono volunteers to try the machine out, and it teleports him just as expected. After Crono's success, Marle wants to try it too. When she does, though, her pendant reacts strangely to the machine; a swirling blue gate opens and Marle vanishes into it, leaving her pendant behind on the telepod. The scattered onlookers are shooed away by Lucca's dad and Lucca wonders what could have gone wrong. The game won't advance until the player directs Crono to the telepod to pick up Marle's pendant, at which point Lucca's dialog indicates that Crono has volunteered to follow Marle through the gate by being teleported while holding her pendant.

Crono's plan works and he is transported to a world that looks similar to his own, but turns out to be quite different. He learns that he is in the year 600 A.D., 400 years earlier than his own time. When he visits Guardia Castle the familiar-looking Queen invites him to stay and tells everyone that he rescued her; apparently, she had previously been lost. Crono visits the Queen privately and discovers that she is actually Marle. Marle looks just like the lost Queen Leene (for whom Leene's Bell was named) and has been able to masquerade as the Queen since arriving. Marle seems happy, but midway through her conversation with Crono she vanishes in a strange blue light.

Fortunately, Lucca arrives from 1000 A.D. to explain to Crono that Marle has fallen afoul of the grandfather paradox. It turns out that Marle is actually Princess Nadia of 100 A.D.'s royal family; she was masquerading as a regular girl to enjoy the Millennial Fair. That makes her a descendant of Leene. Because the search for Leene was called off after Marle arrived, Leene was never rescued and never lived to complete Marle's line of descent. Crono and Lucca depart to find Leene.

At a cathedral, Crono and Lucca find the Queen's treasured coral pin. After they find this clue, the nuns at the cathedral turn into monsters and attack. After they think they've dispatched all of the monsters, they are saved from an ambush by a bipedal anthropomorphic frog. Lucca is initially uneasy with the idea of working with a frog, but concedes that it is better to work together. The strange knight doesn't give his name; he says that "Frog" will do for now. This makes the second character to give a false name in less than an hour of gameplay. Frog is a longsword-wielding knight who speaks in a medieval dialect; more on him in a later article.

The three adventurers encounter a shrine to Magus within the cathedral. Magus is the leader of the Mystics, the enemies of Guardia in the current war. They also encounter doppelgängers of Guardia's King, Queen and two soldier, who try to convince them that their job is done.

Eventually, the three defeat Yakra, a monster henchman of Magus who has been posing as the Chancellor of Guardia. It was he who kidnapped Leene. After her rescue, Leene thanks the characters, but Frog blames himself for Leene's being kidnapped in the first place and runs away to seclusion. Marle reappears and comments that during the interim she has been in a cold, dark and lonely place; she wonders if that is what it feels like to die. Lucca confronts her with her true identity as the Princess, and Marle protests that if she had told Crono she was royalty he wouldn't have been willing to join her at the Fair; the player is free to have Crono agree or disagree with this statement.

Back at the canyon where the gate to 600 A.D. first opened, Lucca explains that she has invented a Gate Key that can open preexisting time gates. She doesn't know why the gates exist in the first place, though. The Gate Key works and all three travel back to the Millennial Fair. Marle wants Crono to take her home to the castle; he agrees. When the two arrive, though, the Chancellor insists that guards arrest Crono. It turns out that Crono is being charged with kidnapping and must stand trial.

Comments

Crono and 1000 A.D.

Crono and his time-period, 1000 A.D., invite immediate identification from the player. Their sparse detail actually enhances this effect. Crono, for example, has no dialog in the game. He clearly speaks in the world of the game, but the player does not see his lines, for he is only the player's surrogate. His only identifiable character traits are his drive and his seeming fearlessness. From a narrative perspective, he is the Hero stripped down to essentials; he chooses, he acts, he drives the plot, he solves the problem, he saves the day... but he does (and is) nothing else. Crono possesses, in the Sartrean sense, being-for-itself. We experience that being vicariously when we play him, albeit through the lens of a being who inhabits heroic fiction. Despite the fact that he is a fictional character, Crono lacks an essence. He is choice and potentiality unfolding in time, a remarkable characteristic that he acquires by being transparent to the player's input. One could argue that by being bound to the heroic role, Crono acts in what Sartre would call bad faith, that he denies his lack of essence by identifying with a role. However, I would argue that the role of protagonist is defined by its very lack of essence. The Hero may possess certain qualities, but they do not define him. At his core is the potential for effective and meaningful choice. Taking on the mantle of the hero, then, is a radical acceptance of being-for-itself.

1000 A.D., while not quite so transparent as Crono, is sort of a "default" time period that we are meant to identify as such. The people there seem more like us than we do, as it were; they speak in plain language and have most of the modern conveniences, but lack technological and culture developments that have yet to be incorporated into the modern self-image. Chrono Trigger's 1000 A.D. really has nothing in common with that time period in the real world, but is more like the vague pseudo-historical world of Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy fiction; it is a staging ground for stories about the unchanging human condition, with all the usual hidden assumptions about that condition. If Crono is being-for-itself, a being constantly creating himself and yet defined only by his exertion of will upon the world, 1000 A.D. is history-for-itself, an era characterized by potentiality and defined only by its relationship to the other eras (note the Millennial Fair, a celebration of the era's pivotal place in relation to the past and future). It is the unfolding time we live in, as opposed to the static time we read about.

Leene's Bell

The ringing of Leene's Bell heralds the game's opening and the meeting of Crono and Marle, indicating that both Crono and the player have embarked on a special journey. On its face, this seems to be our first brush with destiny in the game. Crono and Marle's meeting was destined, and the bell acts a symbol of the adventure that fate has in store for them. We have to look closer to see that the cliché of the fated hero is being dismantled here. For one thing, everyone can hear Leene's Bell -- hell, it's audible from Crono's bedroom! More importantly, within about 15 minutes of gameplay, the player will have traveled to the past and will have the opportunity to rewrite the history of Queen Leene, the woman whom the bell is named after. In fact, we can see the bell being crafted in a smith's home in 600 A.D., if we care to stop in there. In some endings of the game, the bell is even rechristened and named after one of the main characters, so that this supposed arbiter of destiny becomes a memorial to the world-changing choices of the protagonists. It's not that the idea of destiny is being asserted or debunked here, but that the cliché of the fated hero is being introduced into a game dominated by the theme of personal choice, and that this theme subverts the version of destiny found in the diegetic world.

Leene's Bell and the exuberant retrospection of the Millennial Fair both represent a way of looking at history and our place within it. That viewpoint will become increasingly outmoded as the game progresses, leading up to an ending where Crono and the rest will categorically assert their will over any fiat of destiny or history.

Crono's Decision to Follow Marle

Crono's choice here always struck me as fascinating, even before I developed this existentialist reading of the text. It is a tremendous risk for Crono to take, as other characters don't fail to point out, and yet no motive is stated. Crono's lack of dialog prevents him from explaining himself, and the other characters seem impressed with his heroism but don't try to explain it. Here Crono reminds me of Kierkegaard's Knight of Faith. Crono risks his life on a rationally indefensible plan to save a girl whom he barely knows and who might be dead already (or in no danger at all). He makes this choice because it is absurd, like the Knight of Faith. While Kierkegaard's Knight of Faith acts out of religious faith that transcends reason, though, Crono's religion is the narrative position of the Hero. Crono is making a leap to faith with this act. He is becoming the Hero of this story despite the fact that nothing in his world tells him that he is. Again, Crono's transparency is key here. The player knows that Crono is the Hero of this story, which imbues the essence-less Crono with a subtle numinous quality. Diegetically, it might be called "faith."

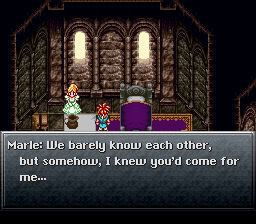

Note that when Crono finds Marle in the past, she tells him that she knew he would come for her, despite the fact that they are almost strangers. This simultaneously reinforces and confuses Crono's status as a champion of choice. It means that Marle detected his role as the Hero who transcends the rational with the power of his will... but how much choice does one really have if a near-stranger can predict one's actions so easily? This contradiction comes from the traditional identification of individuality with existentialism though, and simply doesn't apply to Chrono Trigger's assumptions. In Chrono Trigger, hell is not other people. Contrary to Sartre, who identifies other beings as a constant threat or impediment to the individual, Chrono Trigger emphasizes human interdependence. This is not traditionally existentialist philosophy, but neither is it inherently anti-existentialist. Isn't it valid to recognize the threat of colliding egos and impositions by the Other (as Chrono Trigger repeatedly does), but to find the solution to those threats in collaborative efforts? This formulation seems distinctively Japanese to me, though I confess my limited understanding of Japanese philosophy.

Marle and Mistaken Identity

There are numerous cases of mistaken or concealed identity in Chrono Trigger. Marle's double masquerade is the first. Her real identity is Princess Nadia of the Kingdom of Guardia. We learn from a gossip at the Millennial Fair that the Princess is a bit of a tomboy and makes her father nervous. Nadia poses as a regular girl, Marle, to visit the Fair and spend time with Crono, eager to escape her royal status. When Marle is transported to the past, she is mistaken for the Queen and takes up this role instead, enjoying the attention and the novelty that come with her new position. The irony of fleeing from being a Princess and ending up as a Queen is obvious.

The motif of altered identity is one of the key existentialist statements of Chrono Trigger. We find that identity is never immutable; characters may change profoundly as a result of events in their lives or to achieve some goal, yet even their new forms always contain some seed of the old. In Marle's case, the question of "true" identity is especially problematic, and we sense already that the problem lies as much within Marle as in her repressive surroundings. We know Marle as Marle; her name, clothing and personality throughout the game are those of the Marle identity. Yet, within the first adventure of the game, we learn that this identity is in some sense a sham. So why stick with it? It is because Marle's identity is fragmented. There is no real Princess Nadia yet; Marle plays many roles to suit various audiences, but she has no stable self-image.

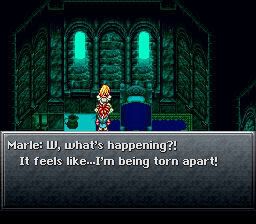

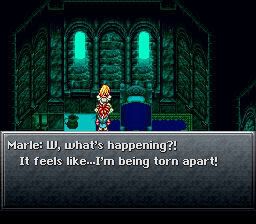

The closest Nadia comes to authenticity is when she pretends to be Marle, but this is still an ultimately unworkable lie, as we see when "Marle" ends up right back in Guardia castle playing the double role of Marle-as-the-Queen. Marle cannot integrate her inescapable status as royalty into her self-image, and so she is ironically doomed to re-assume it whenever she tries to escape. It would be possible to read Marle's disappearance as a metaphor for the self-obliteration she inflicts by taking on a foreign identity. As she states when she is disappearing due to her time-tampering, "I feel like... I'm being torn apart!" I think that this reading, though not intended by the authors, is valid. The metaphor occurs naturally from the circumstances of the scenario. The time-travel cliché of the grandfather paradox is a cautionary trope about humans losing precious things that they take for granted by tampering irresponsibly with dangerous forces. In this case, the dangerous force is identity itself, and the lost treasure is being. Marle has a penchant for deception, no real self-awareness, and is mucking about with her own past; she is reshaping her identity in bad faith. At some point, a person who does this can cease to exist completely, erased altogether by her own self-editing.

Next time: The trial, the ruined future, and Robo's vertigo of choice

But first: Dwarves, dwarves, dwarves!

So for those of you who are in the know about Chrono Trigger and about Existentialism, here's the long and short: Although Chrono Trigger is by no means a heavyweight philosophical text, it has philosophical underpinnings and, more importantly, crafts a broad-ranging pastiche/satire of various pasts and futures as they are imagined in popular culture. As Umberto Eco writes of Casablanca, "the clichés are having a ball" in Chrono Trigger. What's more, the very format of the console RPG creates an experience that is well-suited to exploration of existential questions; Chrono Trigger, like other games of its ilk, presents the player with a complete world and asks him or her to make meaningful choices in that world -- and, yes, to kill some goblins along the way. It's not exactly Being and Nothingness, but it's not Pac-Man, either.

My plan is to play through Chrono Trigger yet again and to look at the statements and assumptions about existence that arise in the game, with special emphasis on Identity, Choice, Subjectivity/Objectivity, Time and Death. It's worth repeating explicitly that I'm not out to prove that complex philosophical statements were deliberately embedded in this video game. Instead, I'm trying to show that the format, the subject matter and the intertextual nature of Chrono Trigger make it possible to read the game as a negotiation of these subjects.

Enough of that. Let's get to the game.

Synopsis, Part One

Chrono Trigger opens with a pendulum swinging repeatedly past the screen, gradually losing energy and finally stopping fully in frame. The title then emerges alongside the pendulum. This image has special significance because, as we will learn much later at a key point in the game, a "Chrono Trigger" is a device that can literally stop time. This is not the usual method of time travel in the game, but a one-time occurrence that nevertheless gives the game its title and gives meaning to this title screen. It's enough for now to point it out and to remember that the very first image of this game, which seems superficially to be about the vast and unstoppable sweep of time, is that of a pendulum ceasing to swing.

Our introduction to Crono and his world is extremely straightforward for a console RPG. We get a moving overhead shot of Crono's town, followed by the ringing of a bell and Crono's Mom opening his bedroom window (cf. Psycho). Crono's Mom identifies the ringing as Leene's Bell; more on that later. We discover from Crono's Mom that the Millennial Fair is beginning today, and that Crono is supposed to meet his inventor friend Lucca there. With that simple introduction, we're out of Crono's house and into the main body of the game.

When Crono visits the Millennial Fair, he bumps into a girl in front of Leene's Bell, knocking her over and causing her to drop her pendant. Predictably, the bell rings. As we learn at the Fair, the bell is said to guarantee a happy and interesting life to those who hear it ring. Crono returns the pendant to the girl. She introduces herself as Marle (after some hesitation about her name) and asks to join Crono. He accepts.

After some hijinks at the fair, the two go to see Lucca's exhibition of her new invention, a "telepod" that can teleport people over a short distance. Crono volunteers to try the machine out, and it teleports him just as expected. After Crono's success, Marle wants to try it too. When she does, though, her pendant reacts strangely to the machine; a swirling blue gate opens and Marle vanishes into it, leaving her pendant behind on the telepod. The scattered onlookers are shooed away by Lucca's dad and Lucca wonders what could have gone wrong. The game won't advance until the player directs Crono to the telepod to pick up Marle's pendant, at which point Lucca's dialog indicates that Crono has volunteered to follow Marle through the gate by being teleported while holding her pendant.

Crono's plan works and he is transported to a world that looks similar to his own, but turns out to be quite different. He learns that he is in the year 600 A.D., 400 years earlier than his own time. When he visits Guardia Castle the familiar-looking Queen invites him to stay and tells everyone that he rescued her; apparently, she had previously been lost. Crono visits the Queen privately and discovers that she is actually Marle. Marle looks just like the lost Queen Leene (for whom Leene's Bell was named) and has been able to masquerade as the Queen since arriving. Marle seems happy, but midway through her conversation with Crono she vanishes in a strange blue light.

Fortunately, Lucca arrives from 1000 A.D. to explain to Crono that Marle has fallen afoul of the grandfather paradox. It turns out that Marle is actually Princess Nadia of 100 A.D.'s royal family; she was masquerading as a regular girl to enjoy the Millennial Fair. That makes her a descendant of Leene. Because the search for Leene was called off after Marle arrived, Leene was never rescued and never lived to complete Marle's line of descent. Crono and Lucca depart to find Leene.

At a cathedral, Crono and Lucca find the Queen's treasured coral pin. After they find this clue, the nuns at the cathedral turn into monsters and attack. After they think they've dispatched all of the monsters, they are saved from an ambush by a bipedal anthropomorphic frog. Lucca is initially uneasy with the idea of working with a frog, but concedes that it is better to work together. The strange knight doesn't give his name; he says that "Frog" will do for now. This makes the second character to give a false name in less than an hour of gameplay. Frog is a longsword-wielding knight who speaks in a medieval dialect; more on him in a later article.

The three adventurers encounter a shrine to Magus within the cathedral. Magus is the leader of the Mystics, the enemies of Guardia in the current war. They also encounter doppelgängers of Guardia's King, Queen and two soldier, who try to convince them that their job is done.

Eventually, the three defeat Yakra, a monster henchman of Magus who has been posing as the Chancellor of Guardia. It was he who kidnapped Leene. After her rescue, Leene thanks the characters, but Frog blames himself for Leene's being kidnapped in the first place and runs away to seclusion. Marle reappears and comments that during the interim she has been in a cold, dark and lonely place; she wonders if that is what it feels like to die. Lucca confronts her with her true identity as the Princess, and Marle protests that if she had told Crono she was royalty he wouldn't have been willing to join her at the Fair; the player is free to have Crono agree or disagree with this statement.

Back at the canyon where the gate to 600 A.D. first opened, Lucca explains that she has invented a Gate Key that can open preexisting time gates. She doesn't know why the gates exist in the first place, though. The Gate Key works and all three travel back to the Millennial Fair. Marle wants Crono to take her home to the castle; he agrees. When the two arrive, though, the Chancellor insists that guards arrest Crono. It turns out that Crono is being charged with kidnapping and must stand trial.

Comments

Crono and 1000 A.D.

Crono and his time-period, 1000 A.D., invite immediate identification from the player. Their sparse detail actually enhances this effect. Crono, for example, has no dialog in the game. He clearly speaks in the world of the game, but the player does not see his lines, for he is only the player's surrogate. His only identifiable character traits are his drive and his seeming fearlessness. From a narrative perspective, he is the Hero stripped down to essentials; he chooses, he acts, he drives the plot, he solves the problem, he saves the day... but he does (and is) nothing else. Crono possesses, in the Sartrean sense, being-for-itself. We experience that being vicariously when we play him, albeit through the lens of a being who inhabits heroic fiction. Despite the fact that he is a fictional character, Crono lacks an essence. He is choice and potentiality unfolding in time, a remarkable characteristic that he acquires by being transparent to the player's input. One could argue that by being bound to the heroic role, Crono acts in what Sartre would call bad faith, that he denies his lack of essence by identifying with a role. However, I would argue that the role of protagonist is defined by its very lack of essence. The Hero may possess certain qualities, but they do not define him. At his core is the potential for effective and meaningful choice. Taking on the mantle of the hero, then, is a radical acceptance of being-for-itself.

1000 A.D., while not quite so transparent as Crono, is sort of a "default" time period that we are meant to identify as such. The people there seem more like us than we do, as it were; they speak in plain language and have most of the modern conveniences, but lack technological and culture developments that have yet to be incorporated into the modern self-image. Chrono Trigger's 1000 A.D. really has nothing in common with that time period in the real world, but is more like the vague pseudo-historical world of Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy fiction; it is a staging ground for stories about the unchanging human condition, with all the usual hidden assumptions about that condition. If Crono is being-for-itself, a being constantly creating himself and yet defined only by his exertion of will upon the world, 1000 A.D. is history-for-itself, an era characterized by potentiality and defined only by its relationship to the other eras (note the Millennial Fair, a celebration of the era's pivotal place in relation to the past and future). It is the unfolding time we live in, as opposed to the static time we read about.

Leene's Bell

The ringing of Leene's Bell heralds the game's opening and the meeting of Crono and Marle, indicating that both Crono and the player have embarked on a special journey. On its face, this seems to be our first brush with destiny in the game. Crono and Marle's meeting was destined, and the bell acts a symbol of the adventure that fate has in store for them. We have to look closer to see that the cliché of the fated hero is being dismantled here. For one thing, everyone can hear Leene's Bell -- hell, it's audible from Crono's bedroom! More importantly, within about 15 minutes of gameplay, the player will have traveled to the past and will have the opportunity to rewrite the history of Queen Leene, the woman whom the bell is named after. In fact, we can see the bell being crafted in a smith's home in 600 A.D., if we care to stop in there. In some endings of the game, the bell is even rechristened and named after one of the main characters, so that this supposed arbiter of destiny becomes a memorial to the world-changing choices of the protagonists. It's not that the idea of destiny is being asserted or debunked here, but that the cliché of the fated hero is being introduced into a game dominated by the theme of personal choice, and that this theme subverts the version of destiny found in the diegetic world.

Leene's Bell and the exuberant retrospection of the Millennial Fair both represent a way of looking at history and our place within it. That viewpoint will become increasingly outmoded as the game progresses, leading up to an ending where Crono and the rest will categorically assert their will over any fiat of destiny or history.

Crono's Decision to Follow Marle

Crono's choice here always struck me as fascinating, even before I developed this existentialist reading of the text. It is a tremendous risk for Crono to take, as other characters don't fail to point out, and yet no motive is stated. Crono's lack of dialog prevents him from explaining himself, and the other characters seem impressed with his heroism but don't try to explain it. Here Crono reminds me of Kierkegaard's Knight of Faith. Crono risks his life on a rationally indefensible plan to save a girl whom he barely knows and who might be dead already (or in no danger at all). He makes this choice because it is absurd, like the Knight of Faith. While Kierkegaard's Knight of Faith acts out of religious faith that transcends reason, though, Crono's religion is the narrative position of the Hero. Crono is making a leap to faith with this act. He is becoming the Hero of this story despite the fact that nothing in his world tells him that he is. Again, Crono's transparency is key here. The player knows that Crono is the Hero of this story, which imbues the essence-less Crono with a subtle numinous quality. Diegetically, it might be called "faith."

Note that when Crono finds Marle in the past, she tells him that she knew he would come for her, despite the fact that they are almost strangers. This simultaneously reinforces and confuses Crono's status as a champion of choice. It means that Marle detected his role as the Hero who transcends the rational with the power of his will... but how much choice does one really have if a near-stranger can predict one's actions so easily? This contradiction comes from the traditional identification of individuality with existentialism though, and simply doesn't apply to Chrono Trigger's assumptions. In Chrono Trigger, hell is not other people. Contrary to Sartre, who identifies other beings as a constant threat or impediment to the individual, Chrono Trigger emphasizes human interdependence. This is not traditionally existentialist philosophy, but neither is it inherently anti-existentialist. Isn't it valid to recognize the threat of colliding egos and impositions by the Other (as Chrono Trigger repeatedly does), but to find the solution to those threats in collaborative efforts? This formulation seems distinctively Japanese to me, though I confess my limited understanding of Japanese philosophy.

Marle and Mistaken Identity

There are numerous cases of mistaken or concealed identity in Chrono Trigger. Marle's double masquerade is the first. Her real identity is Princess Nadia of the Kingdom of Guardia. We learn from a gossip at the Millennial Fair that the Princess is a bit of a tomboy and makes her father nervous. Nadia poses as a regular girl, Marle, to visit the Fair and spend time with Crono, eager to escape her royal status. When Marle is transported to the past, she is mistaken for the Queen and takes up this role instead, enjoying the attention and the novelty that come with her new position. The irony of fleeing from being a Princess and ending up as a Queen is obvious.

The motif of altered identity is one of the key existentialist statements of Chrono Trigger. We find that identity is never immutable; characters may change profoundly as a result of events in their lives or to achieve some goal, yet even their new forms always contain some seed of the old. In Marle's case, the question of "true" identity is especially problematic, and we sense already that the problem lies as much within Marle as in her repressive surroundings. We know Marle as Marle; her name, clothing and personality throughout the game are those of the Marle identity. Yet, within the first adventure of the game, we learn that this identity is in some sense a sham. So why stick with it? It is because Marle's identity is fragmented. There is no real Princess Nadia yet; Marle plays many roles to suit various audiences, but she has no stable self-image.

The closest Nadia comes to authenticity is when she pretends to be Marle, but this is still an ultimately unworkable lie, as we see when "Marle" ends up right back in Guardia castle playing the double role of Marle-as-the-Queen. Marle cannot integrate her inescapable status as royalty into her self-image, and so she is ironically doomed to re-assume it whenever she tries to escape. It would be possible to read Marle's disappearance as a metaphor for the self-obliteration she inflicts by taking on a foreign identity. As she states when she is disappearing due to her time-tampering, "I feel like... I'm being torn apart!" I think that this reading, though not intended by the authors, is valid. The metaphor occurs naturally from the circumstances of the scenario. The time-travel cliché of the grandfather paradox is a cautionary trope about humans losing precious things that they take for granted by tampering irresponsibly with dangerous forces. In this case, the dangerous force is identity itself, and the lost treasure is being. Marle has a penchant for deception, no real self-awareness, and is mucking about with her own past; she is reshaping her identity in bad faith. At some point, a person who does this can cease to exist completely, erased altogether by her own self-editing.

Next time: The trial, the ruined future, and Robo's vertigo of choice

But first: Dwarves, dwarves, dwarves!