Chrono Trigger: An Existentialist Reading (Part III)

This stretch of Chrono Trigger is almost more fun to analyze than it is to play. In terms of gameplay, it's an unexceptional series of dungeon crawls. In story terms, though, it introduces us to two new characters and begins to show the existentialist assumptions that underlie the game's plot.

Synopsis, Part Three

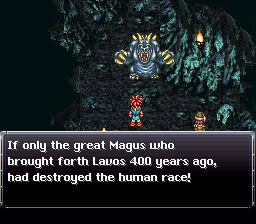

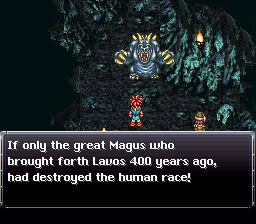

The time gate to 1000 A.D. leads to the village of Medina, which is inhabited by hostile Mystics descended from the Mystic army that went to war with Guardia in 600 A.D. The time gate happens to open from the cupboard in a one Mystic's home. This Mystic is unusually forgiving toward humans regarding the war 400 years ago, but he warns the party to watch out for the other townspeople; as it turns out, the village is extremely hostile, and Mystics will attack the party in various shops and homes in Medina. A visit to the plaza at the center of Medina reveals that Magus is still worshiped here and that the townspeople praise him for creating Lavos. As the party journeys away from Medina, a monster called the Heckran laments that Magus's creation Lavos was unable to destroy the humans 400 years ago. Hoping to defeat Lavos before he is created, the party travels back to 600 A.D. to confront Magus.

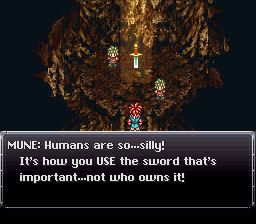

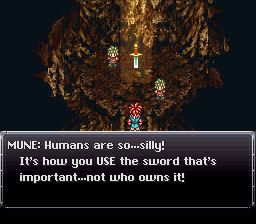

The party crosses Guardia's front lines in 600 A.D., seeking out the Mystics. Along the way, they hear rumors that the prophesied Hero has arrived to slay Magus; the people recognize the Hero because he possesses the Hero Medal. Far to the south, they discover that the Hero is climbing the Denadoro Mountains to claim the Masamune, the fabled sword that can defeat Magus. When the party goes to the Denadoro Mountains they find that the Hero is Tata, a little boy who is in way over his head. Tata flees the mountains, leaving Crono and his friends to continue his quest. Atop the mountain Crono and his allies find two little boys named Masa and Mune. The boys, after complaining that humans don't realize that the real importance of the sword is what it's used for, then resolve to test the party. The party defeats Masa and Mune (who are revealed to be the twin spirits of the sword) and claims half of the Masamune; the other half is missing.

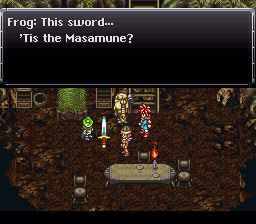

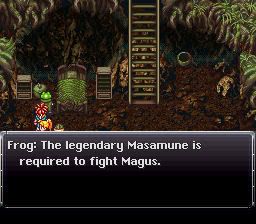

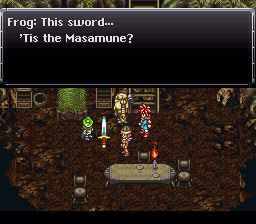

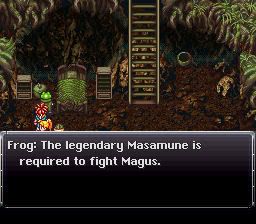

In town, Tata confesses that he found the Hero Medal after a frog-like creature dropped it. He gives the Medal to the party and admits that he is not the Hero. In a hidden burrow in the woods, the party finds Frog and presents him with the Hero Medal and the Masamune. It turns out that Frog has the matching hilt to the blade that the party found in the Denadoro Mountains. The hilt is inscribed with the name of Melchior, a weaponsmith who was present at the Millennial Fair. The party returns to 1000 A.D. to find Melchior and have him repair the Masamune. Melchior informs them that the Masamune can only be repaired using Dreamstone, a rare red rock that humans used as money long ago (this is a mistranslation; in the original Japanese, Melchior states that the rock was more precious than money, which makes a major difference thematically for reasons that become clear later). The party travels to B.C. 65,000,000 to find the Dreamstone.

The time gate to 65,000,000 drops the party in the middle of an attack by dinosaur-people called reptites. Crono and his allies are rescued by Ayla, a mighty cavewoman. Ayla reveals that as the strongest member of Ioka Village, she is its leader and possesses the red rock. The party attends a welcome party that night and Crono wins the rock from Ayla in a contest (soup-guzzling in the North American version, sake-drinking in the original Japanese). When the party awakens the next day, though, Lucca's gate-triggering device has been stolen. Ayla helps the party track their stolen device to the jungle maze, where Ayla's boyfriend Kino admits to stealing it out of jealousy for Ayla's new friendship with Crono. Ayla punishes Kino, but he no longer has the gate key; reptites stole it.

Crono, Ayla and another party member track the reptite thieves to their lair. There Azala, leader of the reptites, is marveling at the device and wondering how the "apes" could have built it; it is obvious that she and her culture are far more advanced than the humans. After a battle with Azala's servant Nizbel, the party reclaims the gate key. Azala flees and the party returns to 1000 A.D. with the Dreamstone. Melchior and Lucca work together to repair the Masamune, which the party then delivers to Frog.

Frog has the party stay in his burrow overnight; at this point we see Frog's history in flashback, as described below in the comments section. Finally, Frog agrees to join the party and help slay Magus. At a mountain to the east Frog finally takes up the Masamune and uses it to cleave open a magically-concealed cave leading under the ocean and toward Magus' Castle.

Comments

The Hero and the Gaze

In this chapter of Chrono Trigger, the legend of the Hero exerts a gaze upon Tata and Frog via society's expectations. Both characters are defined and objectified by society, and both character internalize these definitions. Tata, whose possession of the Hero Medal marks him as the people's foretold savior, begins to believe in the greatness everyone ascribes to him. He plays along with their expectations until he fails, being only a boy, and his own father turns on him. The story is played as comedy, but Tata explicitly decries his father's hypocrisy at the story's end. Tata's only sin was to embrace the identity that was thrust upon him; the "hoax" was never his idea, but a collective self-delusion.

Frog's physical appearance and seclusion prevent others from taking him seriously as a hero. In truth, though, Frog is much more resistant to the idea of his own heroism than anyone else in the game is shown to be. Obviously, he does not reject himself on the basis of appearance, but he chooses equally shallow criteria: the two fetishes of heroism, the Masamune and the aptly-named Hero Medal (or Hero Badge, in the original Japanese). Frog has internalized society's Gaze to the extent that he has forgotten how to choose his own fate; instead, he sees it as being prescribed by his society's meta-narrative and by his physical circumstances. For example, the prophecy says that the Masamune can defeat Magus. Instead of seeking out the Masamune, Frog takes the backwards approach of observing that he does not already have it and concluding that he must not be the Hero. This is precisely the kind of damage that the Gaze can cause. It leads people to see themselves as immutable objects whose choices can all be extrapolated from a concrete identity. Note that while Frog takes this position about himself, the game itself does not. Masa and Mune clearly state that the use of the Masamune is more important that the wielder or even the sword itself. Frog never needed the props of heroism, even if he thought that he did.

The neat twist in Chrono Trigger is that the Gaze is connected to myth. The Destined Hero is an extremely common trope in fantasy literature that won't work in Chrono Trigger because it conflicts with the mutability of history that is central to the game. As a result, we get a send-up of that trope that critiques the Destined Hero by putting him into an existentialist world. In the conventional version of the Destined Hero story, the prophecy/myth of the Hero would lend a transcendent and infallible order to reality. The trope of the Destined Hero presupposes that identity and fate are both fixed; that's why the prophecy works and that's why attempts to fight it are futile. Thus, the myth is more real than reality. Truth can be discovered only by measuring reality against the myth: Can he pull the sword from the stone? Was he born in Bethlehem? Is he strong in the Force? The facts are only methods of divining the Hero's real identity, which is defined by myth, not by the misleading world of phenomena.

In Chrono Trigger, this approach is portrayed as comically (and tragically) misguided. Myth, rather than underlying reality, overlies reality in a way that obscures the truth. The searching eyes of the faithful, which are able to identify the Destined Hero in the conventional version, here convince an inept boy that he is destined for greatness. Meanwhile, the stringent application of the Myth to real life convinces a potential hero -- perhaps the kingdom's only hope -- that he shouldn't bother trying because he doesn't match the prophecy.

Obviously, a lot of this stems from patching a generic fantasy storyline into a broader world that can't abide the same heavy-handed form of destiny as the source material. Still, this storyline reveals Chrono Trigger's implicit position on identity and on fate. Identity is personal and chosen, not archetypal and given; and choice drives fate, not vice versa.

Ayla the Ubermensch

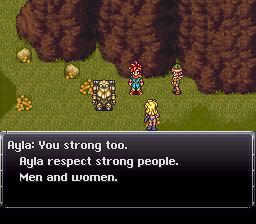

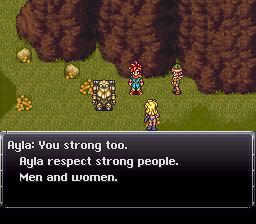

Ayla is probably the least interesting character player character in Chrono Trigger on a personal level, but she's very interesting for our purposes here because she brings a Nietzschean thread of existentialism into the game. Although Ayla is played for comedy in some ways, she is the progenitor of the human race that we spend the game trying to save. She is, in a historical sense, perhaps the game's greatest hero. Strangely for a game that emphasizes moral heroism in the tradition of high fantasy, Chrono Trigger positions Ayla -- the prototype of human heroism -- as an ubermensch instead of a conventional Christ/Hero figure.

To begin with, Ayala's heroism is essentially generative. She's not out to sacrifice herself for anybody, nor is she primarily concerned with destroying the reptites who are competing with the humans to become the dominant species. Instead, Ayla is a fiercely creative force. She is the human race's first great leader and the biological ancestor of great leaders to come. She possesses the Dreamstone, which we will later learn to be the source of human love and hate; in this way she acts as the creator of the human value system. Ayla fights to protect her species, but is willing to severely punish other humans for violating her ethical code, to the point of beating her own boyfriend for stealing (note that this latter act makes the rest of the party uncomfortable because they come from a less primal ethical climate). Like Nietzsche's ubermensch, Ayla worships strength and will as the highest virtues; the game's spin on these values indicates a compromised liberal version of Nietzsche's philosophy, however.

Unlike Nietzsche's ubermensch, whose strength seems merely constructive, Ayla's generative brand of strength links her struggle wholly to her future. This is not so much a conflict with Nietzsche as a different perspective. Nietzsche looks into the future to find the ubermensch and naturally focuses on the ubermensch's ability to transcend the past by constructing a new value system; from this perspective, the ubermensch's completed project is the triumphant culmination of history. Conversely, Chrono Trigger looks at the ubermensch in retrospect as the savage source of present civilization (in the same ambivalent way that today's liberal democracies look back at their imperialist and warlike pasts). The fact that this "ubermensch" is a woman is not to be overlooked. Ayla's virtue is what we might term "heroic motherhood." She grants and defends life, she leads her people in practical and ethical matters by virtue of strength, and she has no need to sacrifice for her people (nor for her generations of future children) because they are her Will engraved on time. Her efforts to defend and support them are not self-effacing, but self-asserting. Ayla is thus just as strongly linked to her social and historical context as Nietzsche's ubermensch is to the physical context of the material world -- again, this results from the assimilation of Nietzsche's worldview into the liberal and communal values that underlie Chrono Trigger.

In the next installment of this series I'll discuss Ayla's meaning further when I write about the world of 65,000,000. It's worth noting now, though I'll delve into it more deeply next time, that Ayla's Will to Power is her strongest link to the ubermensch. Nietzsche and especially Darwin have contributed to a popular conception of a moral vacuum that underlies civilization; it's common for otherwise moral people to concede that morality is an artifice that can't be maintained in the absence of civilized society (in wartime, for instance, in the distant past, or among "primitive" people). In those contexts, many people endorse a Nietzschean veneration of strength and will as virtues in themselves. This popular understanding (or misunderstanding) of Nietzsche is exactly what permits Ayla the Ubermensch to fit seamlessly into a game of high fantasy that exalts peace, harmony and sacrifice. Ayla's uncompromising will to fight, live and seize power is the bedrock upon which more traditionally-moral society is based. This, counter to Nietzsche, is the popular idea of strength-as-virtue; that it is an ugly and necessary step toward a true Christian-like morality of self-sacrifice.

Frog

Frog epitomizes humanity-on-the-border. He is caught between the dynamic creation of meaning and the specter of death, between free will and an identity literally forced upon him, and between the past and the future. As such, his story acts as an overture to all of the complex themes that are woven through the game.

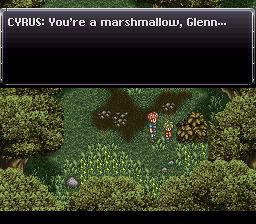

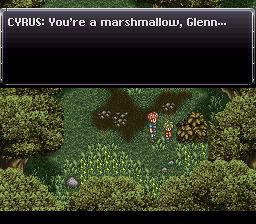

Frog's most prominent struggle is with identity. If we reconstruct his story chronologically using his flashbacks, we find that his life has been a perpetual battle to reconcile the integrity of his personal will with the identities assigned to him by others. As a boy, Glenn was tormented by bullies. When Cyrus saves him in the flashback, he tells him, "You're a marshmallow, Glenn" -- "You're too gentle," in the original Japanese. Glenn responds differently depending upon the translation. In the North American version, Glenn rather spinelessly objects that he hurts when the boys hit him. In the Japanese version, he confides that he knows that it hurts to be hit... even for bullies. In other words, Glenn can't stand the idea of harming others in the way that they harm him. Nietzsche would have something to say about Glenn's value system here, but I don't think this scene serves as a critique of Glenn's morality in the context of the game. Instead, it establishes Glenn's unwillingness to impose his will on others, even when it means sacrificing himself.

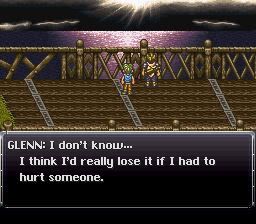

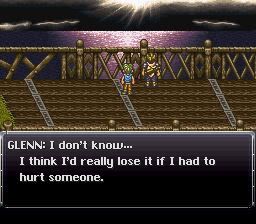

Years later, Cyrus becomes a knight but Glenn refuses to do so, even though his swordsmanship is superior to Cyrus'. Again, Glenn's reasoning differs between the NA and Japanese versions of the game. In the North American version, Glenn thinks he'd "lose it" if he had to hurt someone. In the Japanese version, Glenn fears that he would freeze up and become worthless in a real battle. The general sense of Glenn's story is the same in both versions, and the two versions actually inform each other to paint a more detailed portrait. Glenn is a "marshmallow" in that his identity conforms to the circumstances of his world. He cannot find room to maintain personal integrity in a world inhabited by other people, so he folds. Cyrus is just another influence shaping Glenn's life, which is how a pacifist ends up becoming a useless passenger on a quest to smite evil. Before his transformation, Glenn's identity is dormant. He will not express it because that would require asserting his will upon others.

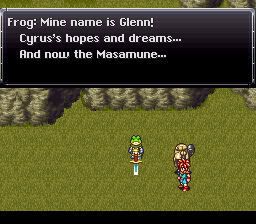

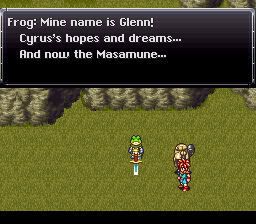

When Cyrus is slain by Magus, Glenn loses what little strength he held by proxy. Magus and Ozzie witness this breakdown and Ozzie delivers a line that serves and the linchpin of Glenn's characterization... but only in the Japanese version. Ozzie comments that Glenn, who is shocked into silence and inaction by Cyrus' defeat, looks like a "frog glared at by a snake," a Japanese idiom akin to our "deer in headlights." It is this comment that inspires Magus to transform Glenn into a frog. Frog's new form, then, is a mark of shame that he earned through his inability to act, his inability to maintain the integrity of his identity by fleeing, fighting or doing something. Appropriately, his punishment is an identity not of his choosing. Frog's outward form, like his inward identity, is now assigned by someone else. Glenn takes up a new form as well as a new name based on others' perception of him; he then takes on Cyrus' old responsibilities to Queen Leene as his new mission in life. Note that Frog is still letting others assign his identity, but now he is doing something. His slow awakening has begun. As noted above, he will not accept the mantle of the Hero until he has the approval of prophecy via the Masamune and the Hero Medal. When he finally takes up the Masamune, though -- which we can now recognize as a supreme act of will, given Glenn's past pacifism and lack of confidence -- Frog states "Mine name is Glenn." Though Frog is still greatly influenced by Cyrus, his decision to fight Magus is his own.

Frog's struggle with identity dovetails with separate existential conflicts. As his story continues, he must struggle to place death in the context of life and to reconcile the facts of the past with the possibilities of the future. Though these wells are dug in Frog's backstory, little water is drawn from them until later in the game, so we will address them then.

Next time: Magus looks into the abyss, Azala has no future, and Lavos puts on the forceps

But first: Gnomes, gnomes, gnomes!

Synopsis, Part Three

The time gate to 1000 A.D. leads to the village of Medina, which is inhabited by hostile Mystics descended from the Mystic army that went to war with Guardia in 600 A.D. The time gate happens to open from the cupboard in a one Mystic's home. This Mystic is unusually forgiving toward humans regarding the war 400 years ago, but he warns the party to watch out for the other townspeople; as it turns out, the village is extremely hostile, and Mystics will attack the party in various shops and homes in Medina. A visit to the plaza at the center of Medina reveals that Magus is still worshiped here and that the townspeople praise him for creating Lavos. As the party journeys away from Medina, a monster called the Heckran laments that Magus's creation Lavos was unable to destroy the humans 400 years ago. Hoping to defeat Lavos before he is created, the party travels back to 600 A.D. to confront Magus.

The party crosses Guardia's front lines in 600 A.D., seeking out the Mystics. Along the way, they hear rumors that the prophesied Hero has arrived to slay Magus; the people recognize the Hero because he possesses the Hero Medal. Far to the south, they discover that the Hero is climbing the Denadoro Mountains to claim the Masamune, the fabled sword that can defeat Magus. When the party goes to the Denadoro Mountains they find that the Hero is Tata, a little boy who is in way over his head. Tata flees the mountains, leaving Crono and his friends to continue his quest. Atop the mountain Crono and his allies find two little boys named Masa and Mune. The boys, after complaining that humans don't realize that the real importance of the sword is what it's used for, then resolve to test the party. The party defeats Masa and Mune (who are revealed to be the twin spirits of the sword) and claims half of the Masamune; the other half is missing.

In town, Tata confesses that he found the Hero Medal after a frog-like creature dropped it. He gives the Medal to the party and admits that he is not the Hero. In a hidden burrow in the woods, the party finds Frog and presents him with the Hero Medal and the Masamune. It turns out that Frog has the matching hilt to the blade that the party found in the Denadoro Mountains. The hilt is inscribed with the name of Melchior, a weaponsmith who was present at the Millennial Fair. The party returns to 1000 A.D. to find Melchior and have him repair the Masamune. Melchior informs them that the Masamune can only be repaired using Dreamstone, a rare red rock that humans used as money long ago (this is a mistranslation; in the original Japanese, Melchior states that the rock was more precious than money, which makes a major difference thematically for reasons that become clear later). The party travels to B.C. 65,000,000 to find the Dreamstone.

The time gate to 65,000,000 drops the party in the middle of an attack by dinosaur-people called reptites. Crono and his allies are rescued by Ayla, a mighty cavewoman. Ayla reveals that as the strongest member of Ioka Village, she is its leader and possesses the red rock. The party attends a welcome party that night and Crono wins the rock from Ayla in a contest (soup-guzzling in the North American version, sake-drinking in the original Japanese). When the party awakens the next day, though, Lucca's gate-triggering device has been stolen. Ayla helps the party track their stolen device to the jungle maze, where Ayla's boyfriend Kino admits to stealing it out of jealousy for Ayla's new friendship with Crono. Ayla punishes Kino, but he no longer has the gate key; reptites stole it.

Crono, Ayla and another party member track the reptite thieves to their lair. There Azala, leader of the reptites, is marveling at the device and wondering how the "apes" could have built it; it is obvious that she and her culture are far more advanced than the humans. After a battle with Azala's servant Nizbel, the party reclaims the gate key. Azala flees and the party returns to 1000 A.D. with the Dreamstone. Melchior and Lucca work together to repair the Masamune, which the party then delivers to Frog.

Frog has the party stay in his burrow overnight; at this point we see Frog's history in flashback, as described below in the comments section. Finally, Frog agrees to join the party and help slay Magus. At a mountain to the east Frog finally takes up the Masamune and uses it to cleave open a magically-concealed cave leading under the ocean and toward Magus' Castle.

Comments

The Hero and the Gaze

In this chapter of Chrono Trigger, the legend of the Hero exerts a gaze upon Tata and Frog via society's expectations. Both characters are defined and objectified by society, and both character internalize these definitions. Tata, whose possession of the Hero Medal marks him as the people's foretold savior, begins to believe in the greatness everyone ascribes to him. He plays along with their expectations until he fails, being only a boy, and his own father turns on him. The story is played as comedy, but Tata explicitly decries his father's hypocrisy at the story's end. Tata's only sin was to embrace the identity that was thrust upon him; the "hoax" was never his idea, but a collective self-delusion.

Frog's physical appearance and seclusion prevent others from taking him seriously as a hero. In truth, though, Frog is much more resistant to the idea of his own heroism than anyone else in the game is shown to be. Obviously, he does not reject himself on the basis of appearance, but he chooses equally shallow criteria: the two fetishes of heroism, the Masamune and the aptly-named Hero Medal (or Hero Badge, in the original Japanese). Frog has internalized society's Gaze to the extent that he has forgotten how to choose his own fate; instead, he sees it as being prescribed by his society's meta-narrative and by his physical circumstances. For example, the prophecy says that the Masamune can defeat Magus. Instead of seeking out the Masamune, Frog takes the backwards approach of observing that he does not already have it and concluding that he must not be the Hero. This is precisely the kind of damage that the Gaze can cause. It leads people to see themselves as immutable objects whose choices can all be extrapolated from a concrete identity. Note that while Frog takes this position about himself, the game itself does not. Masa and Mune clearly state that the use of the Masamune is more important that the wielder or even the sword itself. Frog never needed the props of heroism, even if he thought that he did.

The neat twist in Chrono Trigger is that the Gaze is connected to myth. The Destined Hero is an extremely common trope in fantasy literature that won't work in Chrono Trigger because it conflicts with the mutability of history that is central to the game. As a result, we get a send-up of that trope that critiques the Destined Hero by putting him into an existentialist world. In the conventional version of the Destined Hero story, the prophecy/myth of the Hero would lend a transcendent and infallible order to reality. The trope of the Destined Hero presupposes that identity and fate are both fixed; that's why the prophecy works and that's why attempts to fight it are futile. Thus, the myth is more real than reality. Truth can be discovered only by measuring reality against the myth: Can he pull the sword from the stone? Was he born in Bethlehem? Is he strong in the Force? The facts are only methods of divining the Hero's real identity, which is defined by myth, not by the misleading world of phenomena.

In Chrono Trigger, this approach is portrayed as comically (and tragically) misguided. Myth, rather than underlying reality, overlies reality in a way that obscures the truth. The searching eyes of the faithful, which are able to identify the Destined Hero in the conventional version, here convince an inept boy that he is destined for greatness. Meanwhile, the stringent application of the Myth to real life convinces a potential hero -- perhaps the kingdom's only hope -- that he shouldn't bother trying because he doesn't match the prophecy.

Obviously, a lot of this stems from patching a generic fantasy storyline into a broader world that can't abide the same heavy-handed form of destiny as the source material. Still, this storyline reveals Chrono Trigger's implicit position on identity and on fate. Identity is personal and chosen, not archetypal and given; and choice drives fate, not vice versa.

Ayla the Ubermensch

Ayla is probably the least interesting character player character in Chrono Trigger on a personal level, but she's very interesting for our purposes here because she brings a Nietzschean thread of existentialism into the game. Although Ayla is played for comedy in some ways, she is the progenitor of the human race that we spend the game trying to save. She is, in a historical sense, perhaps the game's greatest hero. Strangely for a game that emphasizes moral heroism in the tradition of high fantasy, Chrono Trigger positions Ayla -- the prototype of human heroism -- as an ubermensch instead of a conventional Christ/Hero figure.

To begin with, Ayala's heroism is essentially generative. She's not out to sacrifice herself for anybody, nor is she primarily concerned with destroying the reptites who are competing with the humans to become the dominant species. Instead, Ayla is a fiercely creative force. She is the human race's first great leader and the biological ancestor of great leaders to come. She possesses the Dreamstone, which we will later learn to be the source of human love and hate; in this way she acts as the creator of the human value system. Ayla fights to protect her species, but is willing to severely punish other humans for violating her ethical code, to the point of beating her own boyfriend for stealing (note that this latter act makes the rest of the party uncomfortable because they come from a less primal ethical climate). Like Nietzsche's ubermensch, Ayla worships strength and will as the highest virtues; the game's spin on these values indicates a compromised liberal version of Nietzsche's philosophy, however.

Unlike Nietzsche's ubermensch, whose strength seems merely constructive, Ayla's generative brand of strength links her struggle wholly to her future. This is not so much a conflict with Nietzsche as a different perspective. Nietzsche looks into the future to find the ubermensch and naturally focuses on the ubermensch's ability to transcend the past by constructing a new value system; from this perspective, the ubermensch's completed project is the triumphant culmination of history. Conversely, Chrono Trigger looks at the ubermensch in retrospect as the savage source of present civilization (in the same ambivalent way that today's liberal democracies look back at their imperialist and warlike pasts). The fact that this "ubermensch" is a woman is not to be overlooked. Ayla's virtue is what we might term "heroic motherhood." She grants and defends life, she leads her people in practical and ethical matters by virtue of strength, and she has no need to sacrifice for her people (nor for her generations of future children) because they are her Will engraved on time. Her efforts to defend and support them are not self-effacing, but self-asserting. Ayla is thus just as strongly linked to her social and historical context as Nietzsche's ubermensch is to the physical context of the material world -- again, this results from the assimilation of Nietzsche's worldview into the liberal and communal values that underlie Chrono Trigger.

In the next installment of this series I'll discuss Ayla's meaning further when I write about the world of 65,000,000. It's worth noting now, though I'll delve into it more deeply next time, that Ayla's Will to Power is her strongest link to the ubermensch. Nietzsche and especially Darwin have contributed to a popular conception of a moral vacuum that underlies civilization; it's common for otherwise moral people to concede that morality is an artifice that can't be maintained in the absence of civilized society (in wartime, for instance, in the distant past, or among "primitive" people). In those contexts, many people endorse a Nietzschean veneration of strength and will as virtues in themselves. This popular understanding (or misunderstanding) of Nietzsche is exactly what permits Ayla the Ubermensch to fit seamlessly into a game of high fantasy that exalts peace, harmony and sacrifice. Ayla's uncompromising will to fight, live and seize power is the bedrock upon which more traditionally-moral society is based. This, counter to Nietzsche, is the popular idea of strength-as-virtue; that it is an ugly and necessary step toward a true Christian-like morality of self-sacrifice.

Frog

Frog epitomizes humanity-on-the-border. He is caught between the dynamic creation of meaning and the specter of death, between free will and an identity literally forced upon him, and between the past and the future. As such, his story acts as an overture to all of the complex themes that are woven through the game.

Frog's most prominent struggle is with identity. If we reconstruct his story chronologically using his flashbacks, we find that his life has been a perpetual battle to reconcile the integrity of his personal will with the identities assigned to him by others. As a boy, Glenn was tormented by bullies. When Cyrus saves him in the flashback, he tells him, "You're a marshmallow, Glenn" -- "You're too gentle," in the original Japanese. Glenn responds differently depending upon the translation. In the North American version, Glenn rather spinelessly objects that he hurts when the boys hit him. In the Japanese version, he confides that he knows that it hurts to be hit... even for bullies. In other words, Glenn can't stand the idea of harming others in the way that they harm him. Nietzsche would have something to say about Glenn's value system here, but I don't think this scene serves as a critique of Glenn's morality in the context of the game. Instead, it establishes Glenn's unwillingness to impose his will on others, even when it means sacrificing himself.

Years later, Cyrus becomes a knight but Glenn refuses to do so, even though his swordsmanship is superior to Cyrus'. Again, Glenn's reasoning differs between the NA and Japanese versions of the game. In the North American version, Glenn thinks he'd "lose it" if he had to hurt someone. In the Japanese version, Glenn fears that he would freeze up and become worthless in a real battle. The general sense of Glenn's story is the same in both versions, and the two versions actually inform each other to paint a more detailed portrait. Glenn is a "marshmallow" in that his identity conforms to the circumstances of his world. He cannot find room to maintain personal integrity in a world inhabited by other people, so he folds. Cyrus is just another influence shaping Glenn's life, which is how a pacifist ends up becoming a useless passenger on a quest to smite evil. Before his transformation, Glenn's identity is dormant. He will not express it because that would require asserting his will upon others.

When Cyrus is slain by Magus, Glenn loses what little strength he held by proxy. Magus and Ozzie witness this breakdown and Ozzie delivers a line that serves and the linchpin of Glenn's characterization... but only in the Japanese version. Ozzie comments that Glenn, who is shocked into silence and inaction by Cyrus' defeat, looks like a "frog glared at by a snake," a Japanese idiom akin to our "deer in headlights." It is this comment that inspires Magus to transform Glenn into a frog. Frog's new form, then, is a mark of shame that he earned through his inability to act, his inability to maintain the integrity of his identity by fleeing, fighting or doing something. Appropriately, his punishment is an identity not of his choosing. Frog's outward form, like his inward identity, is now assigned by someone else. Glenn takes up a new form as well as a new name based on others' perception of him; he then takes on Cyrus' old responsibilities to Queen Leene as his new mission in life. Note that Frog is still letting others assign his identity, but now he is doing something. His slow awakening has begun. As noted above, he will not accept the mantle of the Hero until he has the approval of prophecy via the Masamune and the Hero Medal. When he finally takes up the Masamune, though -- which we can now recognize as a supreme act of will, given Glenn's past pacifism and lack of confidence -- Frog states "Mine name is Glenn." Though Frog is still greatly influenced by Cyrus, his decision to fight Magus is his own.

Frog's struggle with identity dovetails with separate existential conflicts. As his story continues, he must struggle to place death in the context of life and to reconcile the facts of the past with the possibilities of the future. Though these wells are dug in Frog's backstory, little water is drawn from them until later in the game, so we will address them then.

Next time: Magus looks into the abyss, Azala has no future, and Lavos puts on the forceps

But first: Gnomes, gnomes, gnomes!