In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, by Nathaniel Philbrick

The true-life story that was the basis for Moby Dick.

Viking, 1999, 302 pages

The ordeal of the whaleship Essex was an event as mythic in the nineteenth century as the sinking of the Titanic was in the twentieth. In 1819 the Essex left Nantucket for the South Pacific with 20 crew members aboard. In the middle of the South Pacific, the ship was rammed and sunk by an angry sperm whale. The crew drifted for more than 90 days in three tiny whaleboats, succumbing to weather, hunger, and disease and ultimately turning to drastic measures in the fight for survival.

Nathaniel Philbrick uses little-known documents, including a long-lost account written by the ship's cabin boy, and penetrating details about whaling and the Nantucket community to reveal the chilling events surrounding this epic maritime disaster. An intense and mesmerizing read, In the Heart of the Sea is a monumental work of history forever placing the Essex tragedy in the American historical canon.

Though little-known today, the tragedy of the whaleship Essex was one of the major seagoing disasters of the 19th century. It made as great an impression as the sinking of the Titanic a century later. The story became commonly featured in schoolbooks, so most children growing up in America in the decades that followed would have heard of it.

Today, we know of it mostly because it inspired Herman Melville's Moby Dick. Melville actually interviewed the survivors, read all their accounts, and based many of the incidents in his novel on the tragedy of the Essex.

In the Heart of the Sea is not the first book about the Essex. There were many books written about it after the disaster, including at least two by the survivors. The First Mate of the Essex, Owen Chase, wrote his own account after returning to Nantucket. He naturally glosses over any mistakes he made, and casts himself as the hero of the tale. This was the account largely accepted as fact, and used by Melville as the basis for Moby Dick. Nathaniel Philbrick had the advantage of a recently discovered account written by another survivor, with a rather different version of events. In 1960, a journal by the Essex's cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson, was uncovered and published. Nickerson is less complimentary about Owen Chase, and gives a different view of what life aboard the Essex was like, from the perspective of a junior crewmember.

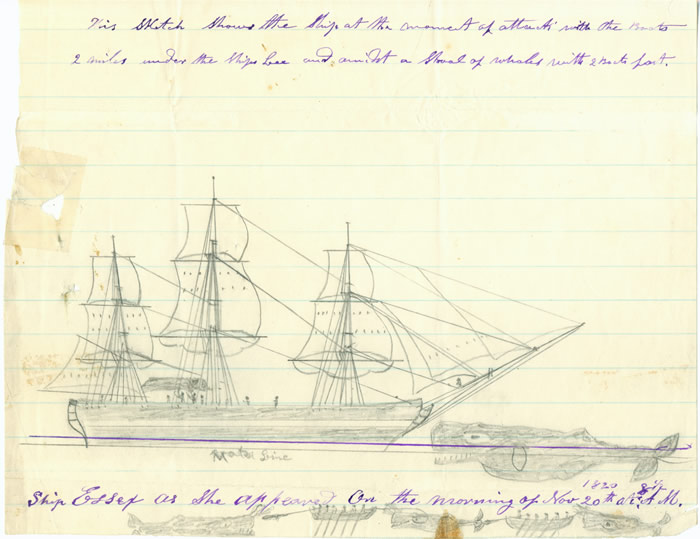

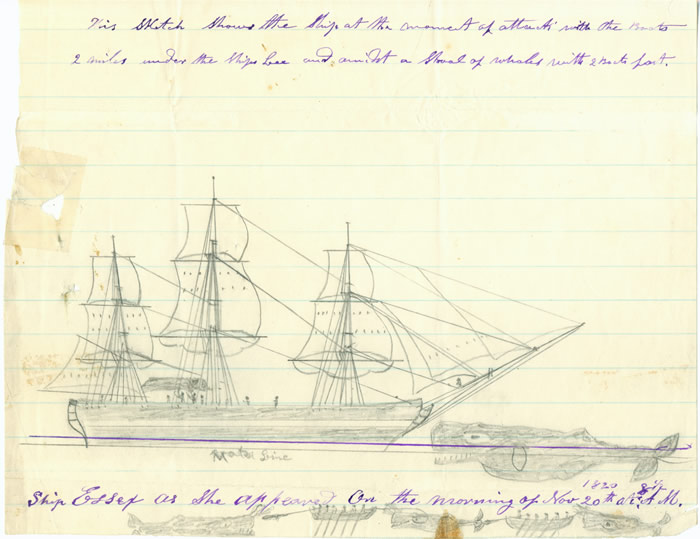

Sketch made by Thomas Nickerson, the cabin boy aboard the Essex.

The Essex was a whaleship out of Nantucket. In the Heart of the Sea describes the Nantucket whaling community, made up mostly of Quakers whose religious beliefs mixed pride, a strong moral (and judgmental) ethos, and avarice. Class and race was a factor on the whaling ships - white sailors naturally were treated better than blacks, though the treatment of African American crewmen on Quaker whaling ships was still better than most other places at the time. (The Quakers were abolitionists.) Being from an established Nantucket whaling family put you on a rung above any "outsiders." Most of the whalers had grown up on Nantucket and had whaling in their blood, knowing from the time they were small boys that they'd be going out to sea to hunt the great beasts that made Nantucket wealthy.

Any sea voyage in 1820 was dangerous, but whaling was particularly dangerous work. The whalers had already started depleting nearby whale hunting grounds, and had to go further and further to fill their holds with whale oil. The Essex expected to be gone for one or two years or more.

Their quarry, the sperm whale, the largest carnivore on Earth, was much larger at that time. Biologists believe that extensive hunting removed the largest whales from the gene pool, so today an adult bull sperm whale rarely exceeds 65 feet, but the one that did in the Essex was estimated to be 85 feet, a size that was large but not spectacular at that time. The whalers had to find the whales, then set out in whaleboats, row up beside the whale, and throw a harpoon into it. This didn't kill the whale - it just sent it fleeing in pain and terror, with the whaleboat dragging behind it, what they called the "Nantucket sleigh ride." Eventually it would tire out, and then the whalers could pull up alongside the exhausted beast and stab it with lances, trying to find the fatal spot. Often they would have to stab it many times.

If this sounds messy and inhumane, it was. Philbrick describes the process, which was related by many whalers. It's pretty gruesome, and a horrible death for the whale. We nearly hunted these magnificent creatures to extinction. (Sperm whales today are no longer considered endangered, but many other species are), harvesting them the way we now harvest oil from the ground, with as little thought to long term consequences. I don't think you have to be a Greenpeace or PETA supporter to find that your sympathies are with the whales.

It is almost surprising how rarely the whales fought back. If they were intelligent enough to recognize the danger, they could easily smash the whaleboats chasing them, but at least in 1820, they didn't often seem to recognize the threat, and when a whale smashed a boat with a slap of its tail or by emerging beneath it, it was more likely to be an accident than a deliberate attack.

For a whale to attack a ship was unheard of. But in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a big bull sperm whale rammed the Essex. It was about a third the size of the ship. A newer, sturdier ship would probably have withstood the assault - the whale was dazed after smashing into the Essex, but then came at it again. It was big enough to smash in the side, and it happened to hit it broadside exactly at its most vulnerable point. To this day, there is no way of knowing why the whale attacked the Essex. Did it somehow recognize the whalers as killers of its kin? Did it mistake the ship for another whale? Was it just insane?

The sailors abandoned ship and then spent months aboard their boats. They made many mistakes. They could have reached Tahiti safely, but were afraid to do so because of lurid tales they'd heard of headhunting cannibals who would sodomize captives before killing and eating them. So instead they tried to reach South America, thousands of miles away. Their boats were separated, and in the end, they were forced to resort to cannibalism, and even drew lots to choose which survivor would be killed to feed the others. Eight survivors were eventually rescued by another whaling ship.

The story of the Essex understandably caused panic throughout the whaling community. What if the whales were finally fighting back? According to Philbrick, in the years that followed there were several more accounts of sperm whales attacking boats and even sinking ships. But it was still pretty rare - the whales certainly were not communicating or planning organized resistance, as appealing as that idea might be.

Amazingly, all eight of the Essex survivors soon went to sea again. What else were they going to do?

In the Heart of the Sea is a great, dramatic account of one of those incredible survival tales that make you thrill at the obstacles faced by men at sea, while hoping you never have to go through anything like that. It's also thoroughly researched, and will educate you about whales, whaling, and the history of early American maritime communities, as well as a full account of what happened to the Essex and their men.

I was still rooting for the whales, though.

In the Heart of the Sea (2015)

This 2015 Ron Howard film, starring Chris Hemsworth as Owen Chase, recreates the Essex disaster, based on Nathaniel Philbrick's book. Filmed like a period piece, it has some good moments, though for me, the film almost but not quite achieved the epic storytelling it was trying for. The acting was only okay (Hemsworth is mostly good at alternating between smirking and angry bellows, making Thor the ideal role for him), so while I thought it was a good movie, I am not surprised that it did not do well at the box office. For the most part, it sticks accurately to the real life sequence of events and the true biographies of the crew. About the only real embellishment was having the whale follow the survivors in the weeks after its attack, surfacing now and then to terrorize them. In reality, the whale that attacked the Essex swam away afterwards - it did not stalk the whalers like a reverse Ahab.

My complete list of book reviews.

Viking, 1999, 302 pages

The ordeal of the whaleship Essex was an event as mythic in the nineteenth century as the sinking of the Titanic was in the twentieth. In 1819 the Essex left Nantucket for the South Pacific with 20 crew members aboard. In the middle of the South Pacific, the ship was rammed and sunk by an angry sperm whale. The crew drifted for more than 90 days in three tiny whaleboats, succumbing to weather, hunger, and disease and ultimately turning to drastic measures in the fight for survival.

Nathaniel Philbrick uses little-known documents, including a long-lost account written by the ship's cabin boy, and penetrating details about whaling and the Nantucket community to reveal the chilling events surrounding this epic maritime disaster. An intense and mesmerizing read, In the Heart of the Sea is a monumental work of history forever placing the Essex tragedy in the American historical canon.

Though little-known today, the tragedy of the whaleship Essex was one of the major seagoing disasters of the 19th century. It made as great an impression as the sinking of the Titanic a century later. The story became commonly featured in schoolbooks, so most children growing up in America in the decades that followed would have heard of it.

Today, we know of it mostly because it inspired Herman Melville's Moby Dick. Melville actually interviewed the survivors, read all their accounts, and based many of the incidents in his novel on the tragedy of the Essex.

In the Heart of the Sea is not the first book about the Essex. There were many books written about it after the disaster, including at least two by the survivors. The First Mate of the Essex, Owen Chase, wrote his own account after returning to Nantucket. He naturally glosses over any mistakes he made, and casts himself as the hero of the tale. This was the account largely accepted as fact, and used by Melville as the basis for Moby Dick. Nathaniel Philbrick had the advantage of a recently discovered account written by another survivor, with a rather different version of events. In 1960, a journal by the Essex's cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson, was uncovered and published. Nickerson is less complimentary about Owen Chase, and gives a different view of what life aboard the Essex was like, from the perspective of a junior crewmember.

Sketch made by Thomas Nickerson, the cabin boy aboard the Essex.

The Essex was a whaleship out of Nantucket. In the Heart of the Sea describes the Nantucket whaling community, made up mostly of Quakers whose religious beliefs mixed pride, a strong moral (and judgmental) ethos, and avarice. Class and race was a factor on the whaling ships - white sailors naturally were treated better than blacks, though the treatment of African American crewmen on Quaker whaling ships was still better than most other places at the time. (The Quakers were abolitionists.) Being from an established Nantucket whaling family put you on a rung above any "outsiders." Most of the whalers had grown up on Nantucket and had whaling in their blood, knowing from the time they were small boys that they'd be going out to sea to hunt the great beasts that made Nantucket wealthy.

Any sea voyage in 1820 was dangerous, but whaling was particularly dangerous work. The whalers had already started depleting nearby whale hunting grounds, and had to go further and further to fill their holds with whale oil. The Essex expected to be gone for one or two years or more.

Their quarry, the sperm whale, the largest carnivore on Earth, was much larger at that time. Biologists believe that extensive hunting removed the largest whales from the gene pool, so today an adult bull sperm whale rarely exceeds 65 feet, but the one that did in the Essex was estimated to be 85 feet, a size that was large but not spectacular at that time. The whalers had to find the whales, then set out in whaleboats, row up beside the whale, and throw a harpoon into it. This didn't kill the whale - it just sent it fleeing in pain and terror, with the whaleboat dragging behind it, what they called the "Nantucket sleigh ride." Eventually it would tire out, and then the whalers could pull up alongside the exhausted beast and stab it with lances, trying to find the fatal spot. Often they would have to stab it many times.

If this sounds messy and inhumane, it was. Philbrick describes the process, which was related by many whalers. It's pretty gruesome, and a horrible death for the whale. We nearly hunted these magnificent creatures to extinction. (Sperm whales today are no longer considered endangered, but many other species are), harvesting them the way we now harvest oil from the ground, with as little thought to long term consequences. I don't think you have to be a Greenpeace or PETA supporter to find that your sympathies are with the whales.

It is almost surprising how rarely the whales fought back. If they were intelligent enough to recognize the danger, they could easily smash the whaleboats chasing them, but at least in 1820, they didn't often seem to recognize the threat, and when a whale smashed a boat with a slap of its tail or by emerging beneath it, it was more likely to be an accident than a deliberate attack.

For a whale to attack a ship was unheard of. But in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a big bull sperm whale rammed the Essex. It was about a third the size of the ship. A newer, sturdier ship would probably have withstood the assault - the whale was dazed after smashing into the Essex, but then came at it again. It was big enough to smash in the side, and it happened to hit it broadside exactly at its most vulnerable point. To this day, there is no way of knowing why the whale attacked the Essex. Did it somehow recognize the whalers as killers of its kin? Did it mistake the ship for another whale? Was it just insane?

The sailors abandoned ship and then spent months aboard their boats. They made many mistakes. They could have reached Tahiti safely, but were afraid to do so because of lurid tales they'd heard of headhunting cannibals who would sodomize captives before killing and eating them. So instead they tried to reach South America, thousands of miles away. Their boats were separated, and in the end, they were forced to resort to cannibalism, and even drew lots to choose which survivor would be killed to feed the others. Eight survivors were eventually rescued by another whaling ship.

The story of the Essex understandably caused panic throughout the whaling community. What if the whales were finally fighting back? According to Philbrick, in the years that followed there were several more accounts of sperm whales attacking boats and even sinking ships. But it was still pretty rare - the whales certainly were not communicating or planning organized resistance, as appealing as that idea might be.

Amazingly, all eight of the Essex survivors soon went to sea again. What else were they going to do?

In the Heart of the Sea is a great, dramatic account of one of those incredible survival tales that make you thrill at the obstacles faced by men at sea, while hoping you never have to go through anything like that. It's also thoroughly researched, and will educate you about whales, whaling, and the history of early American maritime communities, as well as a full account of what happened to the Essex and their men.

I was still rooting for the whales, though.

In the Heart of the Sea (2015)

This 2015 Ron Howard film, starring Chris Hemsworth as Owen Chase, recreates the Essex disaster, based on Nathaniel Philbrick's book. Filmed like a period piece, it has some good moments, though for me, the film almost but not quite achieved the epic storytelling it was trying for. The acting was only okay (Hemsworth is mostly good at alternating between smirking and angry bellows, making Thor the ideal role for him), so while I thought it was a good movie, I am not surprised that it did not do well at the box office. For the most part, it sticks accurately to the real life sequence of events and the true biographies of the crew. About the only real embellishment was having the whale follow the survivors in the weeks after its attack, surfacing now and then to terrorize them. In reality, the whale that attacked the Essex swam away afterwards - it did not stalk the whalers like a reverse Ahab.

My complete list of book reviews.