The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945, by John Toland

A Pulitzer Prize-winning history of World War II from the Japanese perspective.

Random House, 1970, 954 pages

This Pulitzer Prize-winning history of World War II chronicles the dramatic rise and fall of the Japanese empire, from the invasion of Manchuria and China to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Told from the Japanese perspective, The Rising Sun is, in the author’s words, "a factual saga of people caught up in the flood of the most overwhelming war of mankind, told as it happened - muddled, ennobling, disgraceful, frustrating, full of paradox."

In weaving together the historical facts and human drama leading up to and culminating in the war in the Pacific, Toland crafts a riveting and unbiased narrative history.

For many years, this book was the definitive volume on the Pacific War. It won a Pulitzer Price for its in-depth examination of the war from the Japanese perspective, a perspective that (in 1970) was still relatively little-examined and not well understood by the general public. John Toland interviewed survivors of the war on both sides, delved into historical records no one else had yet analyzed, and wrote a compelling, fascinating narrative following the epic tragedy that was Japan's decision to go to war against the West.

Japan: Predestined to Lose

The first thing one quickly understands when reading any well-researched history, or playing a realistic wargame based on the Pacific War, is that Japan never had a chance of winning. This isn't just a matter of 20/20 historical hindsight; nearly all of Japan's senior decision-makers who were not completely swept up in nationalistic fervor and delusions about Japan's divine destiny knew that taking on the United States was a very bad idea and that Japan couldn't hope to win a protracted war. Admiral Yamamoto himself, who like many of Japan's military leaders had spent time in the U.S. and seen her vast resources, advised against war, saying that the U.S.'s industrial and manpower capacity was too immense.

At the height of the war, America, devoted to the "Europe First" policy, was only throwing a fraction of its total output and military capacity into the Pacific, and still the Japanese were hopelessly outmatched. The U.S. was able to just keep pouring more ships and planes and Marines into the theater even as Japan was starving.

One of the things most striking about Toland's narrative is that he lays out all the blunders that were made by both countries before, during, and after the war. These margins where the errors occurred and where history could have been changed are one of the things I find most interesting in non-fiction histories, when competently examined. Let's start with whether or not war was inevitable.

Did we have to go to war with Japan?

The fundamental cause of the war is well understood: the Japanese wanted a colonial empire, and the Western powers didn't want them to have one. When the Japanese invaded China, the U.S. imposed an oil embargo. This would inevitably strangle the Japanese economy, as for all its rising technological prowess, Japan remained a tiny resource-impoverished island. So the Japanese had only two choices: give up their colonial ambitions, or go to war. We know which one they chose.

The question for historians is whether or not this could have been averted.

Henry Stimson

Most historians think that war was inevitable - Japan and the West simply had irreconcilable designs. But Toland presents a great deal of evidence that miscommunication and misfortune had as much to do with Japan and the U.S. being put on a collision course as intransigence. Of course Japan was never going to give up their desire to be a world-class power, which means there was no way they would have accepted the restrictions imposed on them forbidding them fleets or territory on a par with the West. Whether the West could have been persuaded to let Japan take what it saw as its rightful place at the grown-ups table is debatable. But in the first few chapters of The Rising Sun, Toland describes all the negotiating that went on between Japanese and American diplomats. The Japanese were split into factions, just as the Americans were. Some wanted peace no matter what; some were hankering to go to war and really believed their jingoistic propaganda that the spiritual essence of the Japanese people would overcome any enemy. But most Japanese leaders, from the Imperial Palace to the Army and Navy, were more realistic and knew that a war with the U.S. would be, at best, a very difficult one. So there were many frantic talks, including backchannel negotiations among peacemakers on both sides when it became apparent that Secretary of State Henry Stimson and Prime Minister Hideki Tojo were not going to deescalate.

Hideki Tojo

There were a number of tragedies in this situation. Sometimes the precise wording of the phrases used in Japanese or American proposals and counter-proposals was mistranslated, resulting in them being interpreted as more inflexible or duplicitous than intended. This caused both sides to mistrust the other. Sometimes communications arrived late. There was also a lot of labyrinthine political maneuvering on the Japanese side. Political assassinations were commonplace at that time, and the position of the Emperor was always ambiguous. Toland interviewed a very large number of people and read first-hand accounts and so is able to reconstruct many individual talks, even with the Emperor himself, putting the reader in the Imperial throneroom as Hirohito consults with his ministers, and then in telegraph offices where communiques are sent from embassies back to Washington.

Toland doesn't come to a definite conclusion that war could have been avoided, because it's not clear what mutually agreeable concessions might have been made by either side, but what is clear is that both the Japanese and the Americans could see that they were moving towards war and neither side really wanted it. At least initially, everyone except a few warmongers in the Japanese military did everything they could to avoid it.

Unfortunately, diplomatic efforts were for naught, and the Emperor was eventually persuaded to give his blessing to declare war.

Admiral Yamamoto

Isoroku Yamamoto knew very well that Japan had no hope of winning a prolonged war, which was why when war happened and he was put in charge of the Japanese fleet, he planned what he hoped would be quick, devastating knock-out punches - Pearl Harbor and Midway - that would hurt the U.S. so badly that Americans would be persuaded to negotiate an honorable peace before things went too far.

This was extremely unlikely after Pearl Harbor. The Japanese did not seem to realize just how pissed off America would be by this surprise attack - the U.S. would not be so enraged and ready to fight again until 9/11. The unintentionally late formal declaration of war, delivered hours after the attack when it was supposed to have been delivered just prior, certainly didn't help. But a quick peace was a forlorn hope after the debacle at Midway in which, aided by superior intelligence from broken Japanese codes, the U.S. fleet sank four Japanese carriers. Many military historians grade Yamamoto poorly for this badly-executed offensive, which rather than delivering a knock-out punch to the American fleet, proved true his prophecy that "The Americans can lose many battles - we have to win every single one."

The bulk of the book covers the war itself, including all the familiar names like Guam, Guadalcanal, Wake Island, Corregidor, Saipan, Okinawa, and Iwo Jima. Toland does not neglect the British defense of India, the tragic fate of Force Z, which blundered on ahead to its doom despite lack of air cover and thus heralded in the new reality that air power ruled above all, and the multi-sided war in China in which communists and nationalists were alternately fighting each other and the Japanese, with both sides being courted by the Allies. Any military history will cover the battles, but Toland describes them vividly, especially the first-hand accounts from the men in them - the misery and terror, and also the atrocities, like the Bataan Death March, and the miserable conditions of POWs taken back to Japan.

Bataan Death March

One of the things evident in many of these battles was just how much is a roll of the dice. Human error, weather, malfunctioning equipment, pure luck, over and over snatched defeat from the jaws of victory or vice versa. Inevitably, the U.S. was going to win - they simply had more men, more equipment, more resources. The Japanese began going hungry almost as soon as the war began, while the Allies, initially kicked all over the Pacific because they were caught off-guard, began pouring men and ships and, often most importantly (!), food - well-fed troops - into the theater. Still, individual battles often turned on whether or not a particular ship was spotted or whether torpedoes hit. Luck seemed to favor the Americans more often than not, but I found Toland's descriptions particularly informative in recounting how little details about equipment, and the human factor - decisions made by individual commanders, and how the willingness to take risks or an unwillingness to change one's mind - often determined the outcome of a fight.

Who were the war criminals?

Two of the other big questions I find most interesting about World War II are the ones that will probably never be answered satisfactorily.

First: was Emperor Hirohito a war criminal?

Emperor Hirohito, the Shōwa Emperor

There is a particular narrative I heard growing up. It is one that was pushed heavily by the Japanese from approximately the moment the decision was made to surrender until about the time Hirohito died. According to this version of history, Hirohito was a figurehead, a puppet of Japanese military leaders. He had no real decision-making power, and any active resistance on his part would have led to his assassination. Thus, he was not responsible for the war or any of Japan's war crimes; he was an innocent, born to assume a hereditary throne and a position of purely symbolic importance.

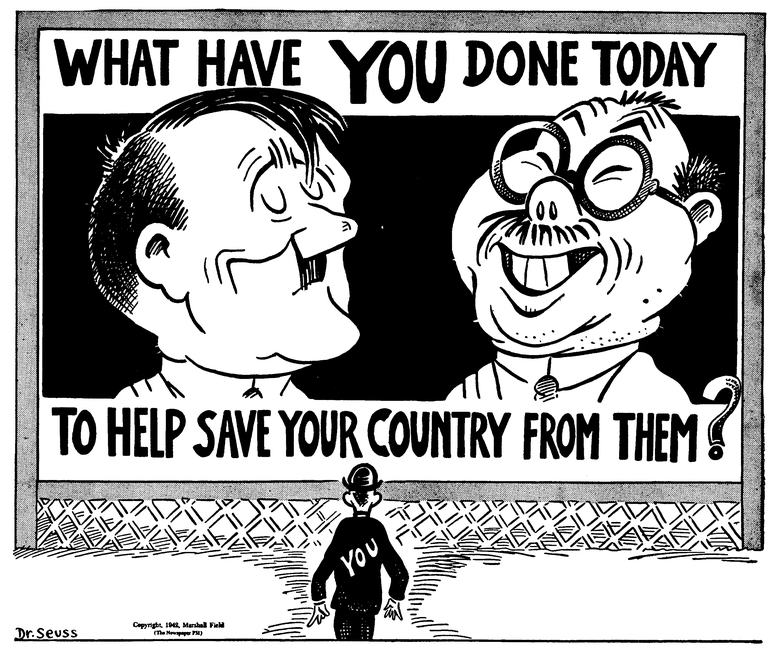

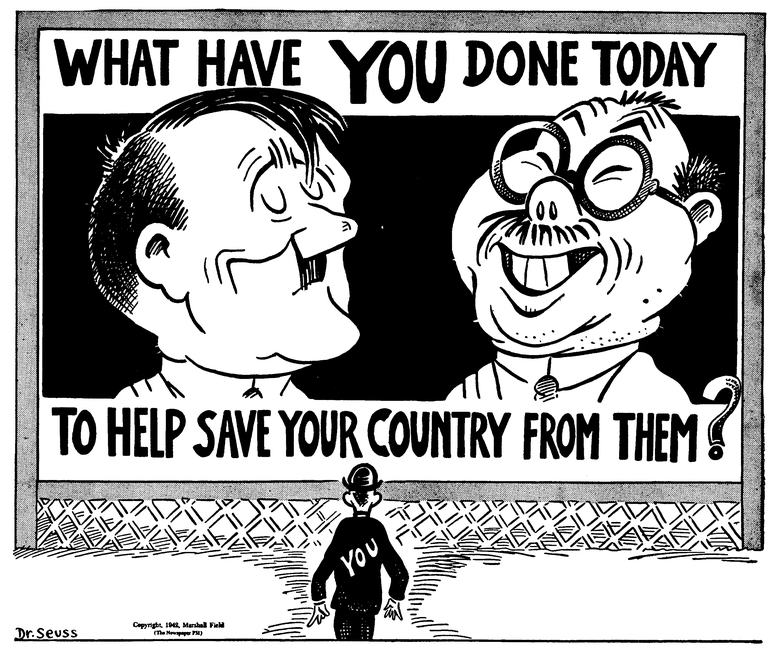

This is in marked contrast to his depiction during the war as an archvillain side by side with Hitler and Mussolini. When he died, in 1989, British tabloids cheered that the "war criminal" was now in hell.

Labeled "Hirohito" but I actually think this is supposed to be Tojo.

While neither view is strictly accurate, it is certainly more complicated than the sanitized version that was accepted for so long. This sanitized version was in fact produced in part by the United States, particularly Douglas MacArthur, from the moment the war ended, as a deliberate strategy to secure faster Japanese cooperation and reconciliation. It was predicted that trying Hirohito as a war criminal - as about one-third of the American public wanted to do at the time - would have resulted in widespread guerrilla warfare and the need for a much longer and more active occupation of the Japanese homeland. When the Japanese finally began negotiating terms of surrender, one of the sticking points, the one thing they tried to carve out of the demand for an "unconditional" surrender, was that the Emperor would retain his status (and, by implication, not be charged with war crimes).

So, how active was Hirohito in the war planning? According to Toland, he was very much involved from the beginning, and had far more than symbolic influence over his cabinet, ministers, and military. Could he have simply forestalled a war by telling them not to do it? Maybe. While political assassination was common, no one would have dared lay a hand on the Emperor himself. And according to the transcripts of cabinet meetings and private conferences Toland obtained, even the most zealous Japanese leaders felt unable to proceed without getting a final say-so from His Majesty. So if Hirohito had been resolutely against a war, it seems likely that the militarists would have had a much harder time getting one.

At the same time, Hirohito was in many ways bound by his position. Traditionally, the Emperor did not make policy, he simply approved it. He wasn't supposed to veto anything or offer his opinion, he was just supposed to bless the decisions that had already been made. Hirohito, especially later in the war, departed from this tradition more than once, shocking his advisors by taking an active role or asking questions during ceremonies that were supposed to be mere formalities.

Personally, the Shōwa Emperor seemed to be a rather quiet, studious man who would have been much happier as a scholarly sovereign and not the Emperor of an expansionist empire. He possessed a genuine, if abstract, concern for the Japanese people, and this motivated him later to accept surrender and even put himself in the hands of the Allies, whatever they might decide to do with him.

He probably also had no direct knowledge of Japanese atrocities. Nobody would have told him such gory and shameful details. So, Hirohito was no Hitler. Still, neither was he the uninvolved innocent that it became politically expedient to portray him as after the war.

Prime Minister Tojo

Hideki Tojo, on the other hand, the Minister of War and Prime Minister, who was tried and executed as a war criminal, undoubtedly deserved it. Initially lukewarm about going to war with the U.S., he became a zealous prosecutor of the war, as well as an increasingly megalomaniacal politician who seized more and more power for himself, quashed all dissent, and most damningly, towards the end when most Japanese leaders were seeing reality and talking about terms of surrender, was one of the holdouts who insisted Japan should fight to the end. Along with a few other generals who were willing to see Japanese civilians take up bamboo spears and die by the millions fighting off an Allied invasion, Tojo deliberately prolonged the fighting well after it was obvious to all that Japan was finished. I think it is not unfair to say that he caused hundreds of thousands of needless deaths on both sides.

Did we have to drop the bomb?

Toland spends only a little time, in the last few chapters, talking about Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the decision leading up to the use of the atomic bomb on Japan. This is another very loaded historical question in which there are people with strong opinions on both sides. Some have argued that the U.S. didn't need to use the bomb - Japan was already negotiating surrender - and that we did for reasons ranging from racism to a desire to demonstrate them as a deterrent to the Soviet Union. Others claim that Japan was fully willing to fight to the last spear-carrying civilian, and that the atomic bombs saved millions of lives on both sides by preventing the need for an invasion.

Entire books have been written about this subject, and Toland, as I said, does not try to dig into it too deeply, but he does describe much of what the Americans and Japanese were thinking and saying at the time. The case he presents would suggest that the truth, unsurprisingly, is somewhere in between.

Yes, the Japanese knew they were going to have to surrender and were already trying to negotiate an "honorable peace." But it's not at all clear that it was the dropping of atomic bombs (I was surprised to learn the Japanese actually knew what they were, and indeed, Japan had already started its own nuclear program, though it hadn't gotten very far) that convinced the holdouts to agree to an unconditional surrender. At the time, the atomic bombs did not seem all that impressive to them. They were already willing to endure horrific casualties, and the firebombing of Tokyo had killed many more people than died at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was more likely the declaration of war by the Soviet Union, when Japan had been hoping the Russians would help them negotiate peace, that was the deciding factor. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki just drove home their inevitable defeat.

Could we have gotten an unconditional surrender when we did without the atomic bombs? We will probably never know. But only a few people at the time really appreciated what new era had been ushered in. Harry Truman, interestingly, said afterwards, and continued to say, that he gave very little thought to the decision to use the bombs, and felt no moral angst about it. Indeed, two more bombs were being prepared for use when the Japanese finally did surrender.

Empire of the Sun, a grand strategic game of the Pacific War. The Japanese start out strong, kicking the shit out of the British and Americans all over the map. By the end of the game, the Japanese player is trying to hold onto a few hexes by his fingernails.

While Toland's book covers the military movements of the Pacific War in detail, it's possibly not the most comprehensive if you want a detailed report on each battle. It does, however, explain just how the Japanese dominated the entire Pacific Theater initially, only to be relentlessly ground down and crushed beneath the heel of a giant they never should have awoken.

If you want one volume that covers the entire span of the war against Japan, I think this monumental work by John Toland leaves very little out, and I highly recommend it to WWII historians. However, I also encourage interested readers to then seek out the more recent works by Ian Toll, who devotes more pages to the American commanders as well, and talks about some of the political issues among the Allies that Toland treats more briefly, as well as going into even more detail about individual battles.

My complete list of book reviews.

Random House, 1970, 954 pages

This Pulitzer Prize-winning history of World War II chronicles the dramatic rise and fall of the Japanese empire, from the invasion of Manchuria and China to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Told from the Japanese perspective, The Rising Sun is, in the author’s words, "a factual saga of people caught up in the flood of the most overwhelming war of mankind, told as it happened - muddled, ennobling, disgraceful, frustrating, full of paradox."

In weaving together the historical facts and human drama leading up to and culminating in the war in the Pacific, Toland crafts a riveting and unbiased narrative history.

For many years, this book was the definitive volume on the Pacific War. It won a Pulitzer Price for its in-depth examination of the war from the Japanese perspective, a perspective that (in 1970) was still relatively little-examined and not well understood by the general public. John Toland interviewed survivors of the war on both sides, delved into historical records no one else had yet analyzed, and wrote a compelling, fascinating narrative following the epic tragedy that was Japan's decision to go to war against the West.

Japan: Predestined to Lose

The first thing one quickly understands when reading any well-researched history, or playing a realistic wargame based on the Pacific War, is that Japan never had a chance of winning. This isn't just a matter of 20/20 historical hindsight; nearly all of Japan's senior decision-makers who were not completely swept up in nationalistic fervor and delusions about Japan's divine destiny knew that taking on the United States was a very bad idea and that Japan couldn't hope to win a protracted war. Admiral Yamamoto himself, who like many of Japan's military leaders had spent time in the U.S. and seen her vast resources, advised against war, saying that the U.S.'s industrial and manpower capacity was too immense.

At the height of the war, America, devoted to the "Europe First" policy, was only throwing a fraction of its total output and military capacity into the Pacific, and still the Japanese were hopelessly outmatched. The U.S. was able to just keep pouring more ships and planes and Marines into the theater even as Japan was starving.

One of the things most striking about Toland's narrative is that he lays out all the blunders that were made by both countries before, during, and after the war. These margins where the errors occurred and where history could have been changed are one of the things I find most interesting in non-fiction histories, when competently examined. Let's start with whether or not war was inevitable.

Did we have to go to war with Japan?

The fundamental cause of the war is well understood: the Japanese wanted a colonial empire, and the Western powers didn't want them to have one. When the Japanese invaded China, the U.S. imposed an oil embargo. This would inevitably strangle the Japanese economy, as for all its rising technological prowess, Japan remained a tiny resource-impoverished island. So the Japanese had only two choices: give up their colonial ambitions, or go to war. We know which one they chose.

The question for historians is whether or not this could have been averted.

Henry Stimson

Most historians think that war was inevitable - Japan and the West simply had irreconcilable designs. But Toland presents a great deal of evidence that miscommunication and misfortune had as much to do with Japan and the U.S. being put on a collision course as intransigence. Of course Japan was never going to give up their desire to be a world-class power, which means there was no way they would have accepted the restrictions imposed on them forbidding them fleets or territory on a par with the West. Whether the West could have been persuaded to let Japan take what it saw as its rightful place at the grown-ups table is debatable. But in the first few chapters of The Rising Sun, Toland describes all the negotiating that went on between Japanese and American diplomats. The Japanese were split into factions, just as the Americans were. Some wanted peace no matter what; some were hankering to go to war and really believed their jingoistic propaganda that the spiritual essence of the Japanese people would overcome any enemy. But most Japanese leaders, from the Imperial Palace to the Army and Navy, were more realistic and knew that a war with the U.S. would be, at best, a very difficult one. So there were many frantic talks, including backchannel negotiations among peacemakers on both sides when it became apparent that Secretary of State Henry Stimson and Prime Minister Hideki Tojo were not going to deescalate.

Hideki Tojo

There were a number of tragedies in this situation. Sometimes the precise wording of the phrases used in Japanese or American proposals and counter-proposals was mistranslated, resulting in them being interpreted as more inflexible or duplicitous than intended. This caused both sides to mistrust the other. Sometimes communications arrived late. There was also a lot of labyrinthine political maneuvering on the Japanese side. Political assassinations were commonplace at that time, and the position of the Emperor was always ambiguous. Toland interviewed a very large number of people and read first-hand accounts and so is able to reconstruct many individual talks, even with the Emperor himself, putting the reader in the Imperial throneroom as Hirohito consults with his ministers, and then in telegraph offices where communiques are sent from embassies back to Washington.

Toland doesn't come to a definite conclusion that war could have been avoided, because it's not clear what mutually agreeable concessions might have been made by either side, but what is clear is that both the Japanese and the Americans could see that they were moving towards war and neither side really wanted it. At least initially, everyone except a few warmongers in the Japanese military did everything they could to avoid it.

Unfortunately, diplomatic efforts were for naught, and the Emperor was eventually persuaded to give his blessing to declare war.

Admiral Yamamoto

Isoroku Yamamoto knew very well that Japan had no hope of winning a prolonged war, which was why when war happened and he was put in charge of the Japanese fleet, he planned what he hoped would be quick, devastating knock-out punches - Pearl Harbor and Midway - that would hurt the U.S. so badly that Americans would be persuaded to negotiate an honorable peace before things went too far.

This was extremely unlikely after Pearl Harbor. The Japanese did not seem to realize just how pissed off America would be by this surprise attack - the U.S. would not be so enraged and ready to fight again until 9/11. The unintentionally late formal declaration of war, delivered hours after the attack when it was supposed to have been delivered just prior, certainly didn't help. But a quick peace was a forlorn hope after the debacle at Midway in which, aided by superior intelligence from broken Japanese codes, the U.S. fleet sank four Japanese carriers. Many military historians grade Yamamoto poorly for this badly-executed offensive, which rather than delivering a knock-out punch to the American fleet, proved true his prophecy that "The Americans can lose many battles - we have to win every single one."

The bulk of the book covers the war itself, including all the familiar names like Guam, Guadalcanal, Wake Island, Corregidor, Saipan, Okinawa, and Iwo Jima. Toland does not neglect the British defense of India, the tragic fate of Force Z, which blundered on ahead to its doom despite lack of air cover and thus heralded in the new reality that air power ruled above all, and the multi-sided war in China in which communists and nationalists were alternately fighting each other and the Japanese, with both sides being courted by the Allies. Any military history will cover the battles, but Toland describes them vividly, especially the first-hand accounts from the men in them - the misery and terror, and also the atrocities, like the Bataan Death March, and the miserable conditions of POWs taken back to Japan.

Bataan Death March

One of the things evident in many of these battles was just how much is a roll of the dice. Human error, weather, malfunctioning equipment, pure luck, over and over snatched defeat from the jaws of victory or vice versa. Inevitably, the U.S. was going to win - they simply had more men, more equipment, more resources. The Japanese began going hungry almost as soon as the war began, while the Allies, initially kicked all over the Pacific because they were caught off-guard, began pouring men and ships and, often most importantly (!), food - well-fed troops - into the theater. Still, individual battles often turned on whether or not a particular ship was spotted or whether torpedoes hit. Luck seemed to favor the Americans more often than not, but I found Toland's descriptions particularly informative in recounting how little details about equipment, and the human factor - decisions made by individual commanders, and how the willingness to take risks or an unwillingness to change one's mind - often determined the outcome of a fight.

Who were the war criminals?

Two of the other big questions I find most interesting about World War II are the ones that will probably never be answered satisfactorily.

First: was Emperor Hirohito a war criminal?

Emperor Hirohito, the Shōwa Emperor

There is a particular narrative I heard growing up. It is one that was pushed heavily by the Japanese from approximately the moment the decision was made to surrender until about the time Hirohito died. According to this version of history, Hirohito was a figurehead, a puppet of Japanese military leaders. He had no real decision-making power, and any active resistance on his part would have led to his assassination. Thus, he was not responsible for the war or any of Japan's war crimes; he was an innocent, born to assume a hereditary throne and a position of purely symbolic importance.

This is in marked contrast to his depiction during the war as an archvillain side by side with Hitler and Mussolini. When he died, in 1989, British tabloids cheered that the "war criminal" was now in hell.

Labeled "Hirohito" but I actually think this is supposed to be Tojo.

While neither view is strictly accurate, it is certainly more complicated than the sanitized version that was accepted for so long. This sanitized version was in fact produced in part by the United States, particularly Douglas MacArthur, from the moment the war ended, as a deliberate strategy to secure faster Japanese cooperation and reconciliation. It was predicted that trying Hirohito as a war criminal - as about one-third of the American public wanted to do at the time - would have resulted in widespread guerrilla warfare and the need for a much longer and more active occupation of the Japanese homeland. When the Japanese finally began negotiating terms of surrender, one of the sticking points, the one thing they tried to carve out of the demand for an "unconditional" surrender, was that the Emperor would retain his status (and, by implication, not be charged with war crimes).

So, how active was Hirohito in the war planning? According to Toland, he was very much involved from the beginning, and had far more than symbolic influence over his cabinet, ministers, and military. Could he have simply forestalled a war by telling them not to do it? Maybe. While political assassination was common, no one would have dared lay a hand on the Emperor himself. And according to the transcripts of cabinet meetings and private conferences Toland obtained, even the most zealous Japanese leaders felt unable to proceed without getting a final say-so from His Majesty. So if Hirohito had been resolutely against a war, it seems likely that the militarists would have had a much harder time getting one.

At the same time, Hirohito was in many ways bound by his position. Traditionally, the Emperor did not make policy, he simply approved it. He wasn't supposed to veto anything or offer his opinion, he was just supposed to bless the decisions that had already been made. Hirohito, especially later in the war, departed from this tradition more than once, shocking his advisors by taking an active role or asking questions during ceremonies that were supposed to be mere formalities.

Personally, the Shōwa Emperor seemed to be a rather quiet, studious man who would have been much happier as a scholarly sovereign and not the Emperor of an expansionist empire. He possessed a genuine, if abstract, concern for the Japanese people, and this motivated him later to accept surrender and even put himself in the hands of the Allies, whatever they might decide to do with him.

He probably also had no direct knowledge of Japanese atrocities. Nobody would have told him such gory and shameful details. So, Hirohito was no Hitler. Still, neither was he the uninvolved innocent that it became politically expedient to portray him as after the war.

Prime Minister Tojo

Hideki Tojo, on the other hand, the Minister of War and Prime Minister, who was tried and executed as a war criminal, undoubtedly deserved it. Initially lukewarm about going to war with the U.S., he became a zealous prosecutor of the war, as well as an increasingly megalomaniacal politician who seized more and more power for himself, quashed all dissent, and most damningly, towards the end when most Japanese leaders were seeing reality and talking about terms of surrender, was one of the holdouts who insisted Japan should fight to the end. Along with a few other generals who were willing to see Japanese civilians take up bamboo spears and die by the millions fighting off an Allied invasion, Tojo deliberately prolonged the fighting well after it was obvious to all that Japan was finished. I think it is not unfair to say that he caused hundreds of thousands of needless deaths on both sides.

Did we have to drop the bomb?

Toland spends only a little time, in the last few chapters, talking about Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the decision leading up to the use of the atomic bomb on Japan. This is another very loaded historical question in which there are people with strong opinions on both sides. Some have argued that the U.S. didn't need to use the bomb - Japan was already negotiating surrender - and that we did for reasons ranging from racism to a desire to demonstrate them as a deterrent to the Soviet Union. Others claim that Japan was fully willing to fight to the last spear-carrying civilian, and that the atomic bombs saved millions of lives on both sides by preventing the need for an invasion.

Entire books have been written about this subject, and Toland, as I said, does not try to dig into it too deeply, but he does describe much of what the Americans and Japanese were thinking and saying at the time. The case he presents would suggest that the truth, unsurprisingly, is somewhere in between.

Yes, the Japanese knew they were going to have to surrender and were already trying to negotiate an "honorable peace." But it's not at all clear that it was the dropping of atomic bombs (I was surprised to learn the Japanese actually knew what they were, and indeed, Japan had already started its own nuclear program, though it hadn't gotten very far) that convinced the holdouts to agree to an unconditional surrender. At the time, the atomic bombs did not seem all that impressive to them. They were already willing to endure horrific casualties, and the firebombing of Tokyo had killed many more people than died at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was more likely the declaration of war by the Soviet Union, when Japan had been hoping the Russians would help them negotiate peace, that was the deciding factor. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki just drove home their inevitable defeat.

Could we have gotten an unconditional surrender when we did without the atomic bombs? We will probably never know. But only a few people at the time really appreciated what new era had been ushered in. Harry Truman, interestingly, said afterwards, and continued to say, that he gave very little thought to the decision to use the bombs, and felt no moral angst about it. Indeed, two more bombs were being prepared for use when the Japanese finally did surrender.

Empire of the Sun, a grand strategic game of the Pacific War. The Japanese start out strong, kicking the shit out of the British and Americans all over the map. By the end of the game, the Japanese player is trying to hold onto a few hexes by his fingernails.

While Toland's book covers the military movements of the Pacific War in detail, it's possibly not the most comprehensive if you want a detailed report on each battle. It does, however, explain just how the Japanese dominated the entire Pacific Theater initially, only to be relentlessly ground down and crushed beneath the heel of a giant they never should have awoken.

If you want one volume that covers the entire span of the war against Japan, I think this monumental work by John Toland leaves very little out, and I highly recommend it to WWII historians. However, I also encourage interested readers to then seek out the more recent works by Ian Toll, who devotes more pages to the American commanders as well, and talks about some of the political issues among the Allies that Toland treats more briefly, as well as going into even more detail about individual battles.

My complete list of book reviews.