Book Review: Zachary Taylor, by John S.D. Eisenhower

Potus #12: "Old Rough and Ready" wasn't ready for the White House.

Times Books, 2008, 192 pages

The rough-hewn general who rose to the nation's highest office, and whose presidency witnessed the first political skirmishes that would lead to the Civil War.

Zachary Taylor was a soldier's soldier, a man who lived up to his nickname, "Old Rough and Ready." Having risen through the ranks of the U.S. Army, he achieved his greatest success in the Mexican War, propelling him to the nation's highest office in the election of 1848. He was the first man to have been elected president without having held a lower political office.

John S. D. Eisenhower, the son of another soldier-president, shows how Taylor rose to the presidency, where he confronted the most contentious political issue of his age: slavery. The political storm reached a crescendo in 1849, when California, newly populated after the Gold Rush, applied for statehood with an anti- slavery constitution, an event that upset the delicate balance of slave and free states and pushed both sides to the brink. As the acrimonious debate intensified, Taylor stood his ground in favor of California's admission-despite being a slaveholder himself-but in July 1850 he unexpectedly took ill, and within a week he was dead. His truncated presidency had exposed the fateful rift that would soon tear the country apart.

Slogging through the biographies of presidents leading up to the Civil War is like reading prequel novels: they're full of interesting characters and background details in a story whose ending you already know. In a sense this is true of any history book, but until the war, there was an almost endearing belief by everyone, North and South, that we'll somehow find a resolution and hold the country together. As names like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis begin to join that upstart congressman from Illinois on the stage, there is a sense of inevitable futility in their projects.

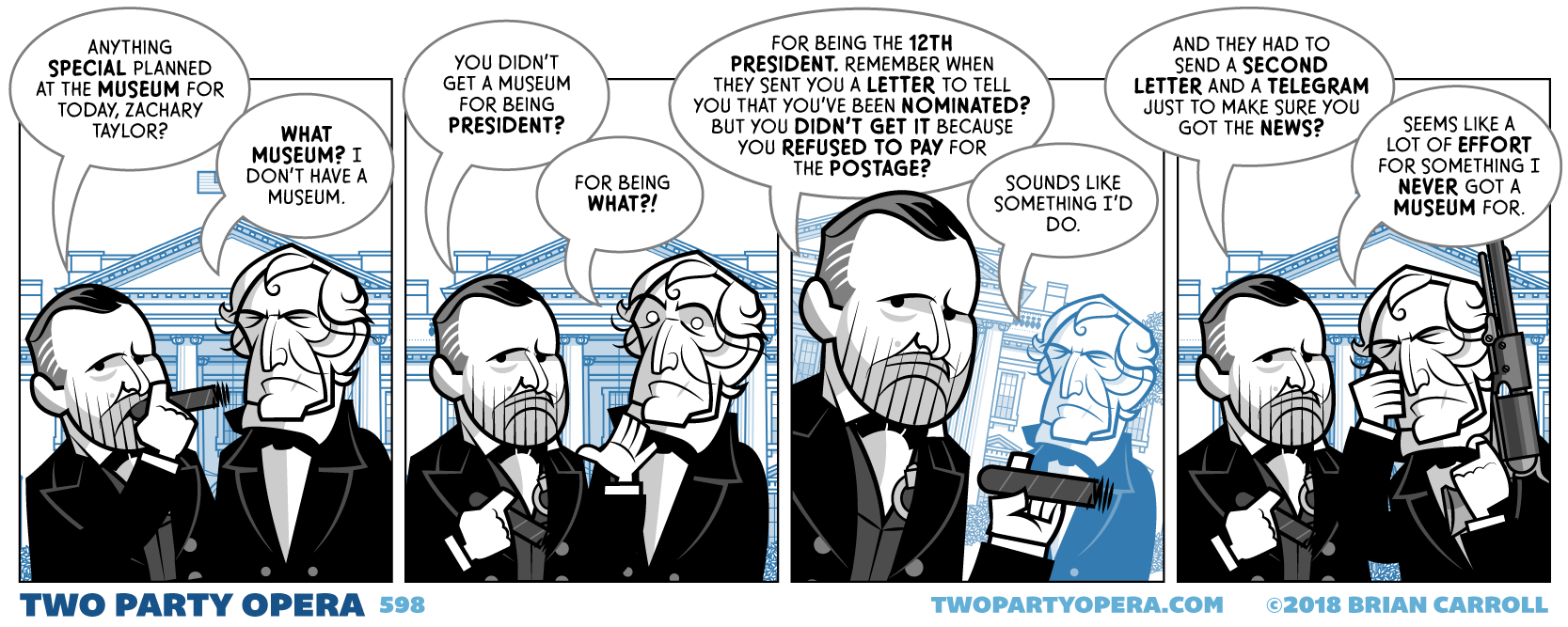

Zachary Taylor was the second president to die in office, only sixteen months into his term. Unlike William Henry Harrison, the first POTUS to die in office, he at least had some time to be president, but at the time of his sudden illness and death, his administration had not done much, and his only real accomplishment as president was signing the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, which settled tensions between Britain and the United States over Central America and the future Panama Canal.

So I was intrigued by the thesis presented in this book's introduction, that the almost unremembered twelfth president might have prevented the Civil War had he lived. The author of this biography, John S.D. Eisenhower, was the son of President Dwight Eisenhower, so presumably he knew a few things about presidents. (John Eisenhower had a pretty distinguished career of his own and later became a military historian.)

Yet Another Virginian Slaveholder

A common thread through most early presidential biographies is the preeminence of Virginia as, at one time, probably the most influential state in the union, and how many presidents came from there. Taylor was born in Virginia in 1784, though he grew up in Kentucky and owned plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana. Like so many of his peers, though, he was one of those men who viewed slavery as a sort of necessary evil that he would have preferred didn't exist, while still benefiting from it. As a military officer in the field for most of his life, he probably had little direct interaction with slaves. But the fact that he was a slave owner who was secretly against expanding slavery would become very significant when he became president, and is probably the reason for Eisenhower's judgment that he could possibly have steered the country away from a war over slavery.

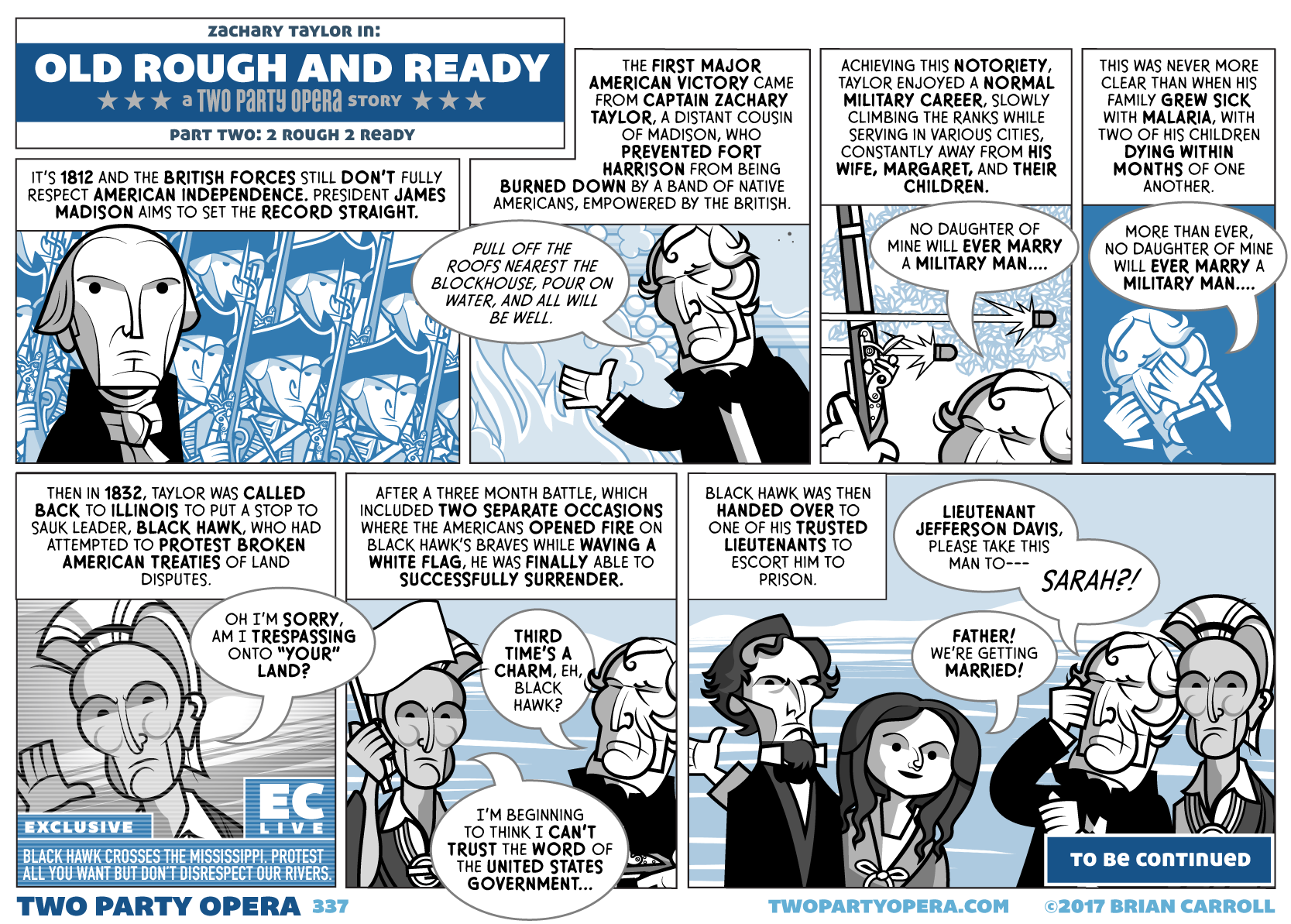

Old Rough and Ready

Like many undistinguished presidents, even those who survived their term in office, Zachary Taylor's life and career before becoming president is more interesting than his presidency. He was a military man for most of his life, with a career that began during the War of 1812 and continued through the Mexican-American War, during which he was simultaneously one of the two commanding generals over American forces and a nascent presidential candidate.

Taylor's life and career in many ways paralleled that of his mentor, William Henry Harrison. Harrison praised Taylor's performance during the War of 1812. Like Harrison, Taylor spent most of the war fighting Indians in the interior. Taylor continued to make his reputation as an Indian fighter, leading American forces in the Black Hawk and Seminole wars. He acquired the nickname "Old Rough and Ready" during this time, for being the kind of officer who rode and camped and fought with his troops and shared all of their hardships.

My daughter will never marry a soldier!

Taylor's wife was Margaret "Peggy" née Smith, described by multiple sources as "fat and motherly." She suffered greatly from her husband's frequent campaigns, as well as multiple childbirths. She was a semi-invalid and supposedly promised God to remain a recluse if her husband came home safely from his various campaigns. She evidently kept this promise, as when Taylor became President, the unwilling First Lady (she actually prayed for her husband to lose the election) remained secluded on the second floor of the White House and let her daughter take on the role of hostess.

There are not a lot of details about Taylor's personal life and habits in this book, probably because while Taylor did write letters, he wasn't highly educated or philosophical, and much of his correspondence was stored in his son's house in Baton Rouge, which was burned by the Union Army during the Civil War. But generally, he seems to have been a plain, honest, and unsophisticated (not to say unintelligent) man who mostly enjoyed being a soldier but also recognized what a hard life it was, especially for his family. Long periods of separation from his wife made them both unhappy, so he became extremely determined not to allow his daughter to marry a military man and suffer the same hardships.

This led to a story as old as time: his 18-year-old daughter Sarah fell in love with an officer, and forbidden by her father to see him, the two lovers conspired to meet anyway, and eventually married, without her father's blessing or attendance.

That officer's name? Jefferson Davis.

Taylor and Davis were estranged after this, even after (or because of) Sarah's untimely death, which left both her father and her widowed husband devastated. Eventually, however, Taylor and Davis would reconcile, when Davis (along with many other future Confederate leaders such as Robert E. Lee ) would serve under him during the Mexican-American War.

The Mexican-American War

At first the Mexicans showed little hostility. In the afternoon, in fact, a group of young women emerged from behind the line of sentries and came down the bank of the river. They disrobed in front of the spectators on both sides and plunged into the water for a swim. A few American officers who were already in the river swam toward them. The Mexican sentries on the opposite bank let the Americans reach almost to the middle before letting it be known that they were to go no farther. The young officers blew kisses to the tawny damsels, who laughed and returned the compliments. Both groups then swam back to their respective shores.

Despite this light-hearted beginning, the Mexican-American War was a bloody affair that was as political as it was military, and while Eisenhower goes into some detail on both the diplomacy and the battles, the main significance for Taylor is that it made him a national figure and presidential candidate, while also hardening the mutual dislike between himself and President Polk.

Polk had initially chosen Taylor over General Winfield Scott to command American troops in Mexico because Scott was a Whig whereas Taylor had until that point appeared relatively apolitical. However, Taylor had often been unhappy at the commands he was given, and he felt slighted by a decision from Polk regarding the precedence of regular ranks over brevet ranks. (Taylor had been given the brevet rank of Major General.) After Taylor captured Monterrey, he more or less ignored Polk's wishes and signed a temporary truce with the Mexican general, allowing him to withdraw most of his troops. Polk sent Winfield Scott to take most of Taylor's troops, which may have backfired, as Taylor then had to fight General Santa Anna with a much smaller force. Outnumbered about three to one, the Americans inflicted far greater casualties against the Mexican forces at the Battle of Buena Vista. After Santa Anna withdrew, both sides claimed victory, but combined with General Scott's landing at Veracruz, these two battles more or less ended the war. The Battle of Buena Vista overshadowed Scott's clear triumph at Veracruz (perhaps because of numerous tragic losses, such as the son of Senator Henry Clay), and Taylor became a bonafide national hero.

The Election of 1848

"It has never entered my head, nor is it likely to enter the head of any other person."

Prior to becoming a presidential nominee, Zachary Taylor had spent most of his life avoiding politics, to the point that he didn't even vote. He wasn't lacking in ambition, but his ambitions had mostly concerned climbing the ranks in the Army. It seems to have been in large part a desire not to serve under a president he'd grown to dislike (James Polk) that turned him political.

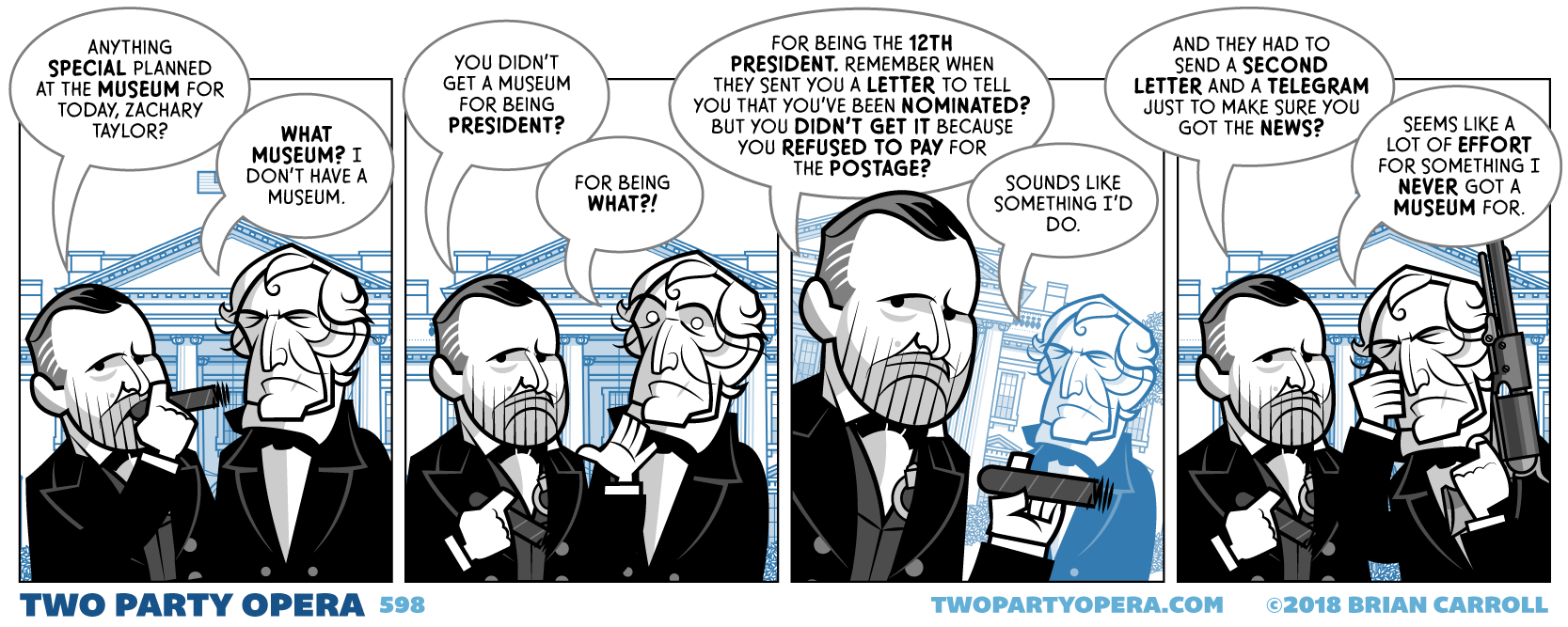

Taylor-for-President clubs had already started while he was still in Mexico, but his nomination seems to have come about as almost unplanned and unanticipated by everyone including himself. He was being courted by both the Democrats and Whigs while refusing to align himself with either party, until finally in early 1848 he was persuaded to declare himself for the Whigs.

His rivals for the Whig nomination were his frenemies General Winfield Scott and perpetual presidential candidate Henry Clay, but the Whigs eventually decided to go with what had worked last time and nominated the war hero, making Taylor the second former general to become a Whig President. Unfortunately, William Henry Harrison would prove to be another precedent for Taylor.

Since Polk was keeping his promise not to run for reelection, Taylor faced Lewis Cass for the Democrats and in one of the most remarkable heel turns in American history, a third-party bid by former President Martin Van Buren and Charles Adams (son of John Quincy Adams), who had started the Free Soil Party. He captured a majority of electoral votes and a plurality of the popular vote, and would be the last president elected before the Republican/Democrat two-party system would control American politics forever after.

The Curse of Whig Generals

Taylor was technically still a commissioned officer when he was elected president, which made for an awkward few months for his commanding officer and former rival, General Winfield Scott.

As a president, Zachary Taylor was unremarkable, and not just because he died early. James Polk, who received him courteously enough when he arrived in Washington, judged him to be crude and almost illiterate (not really true).

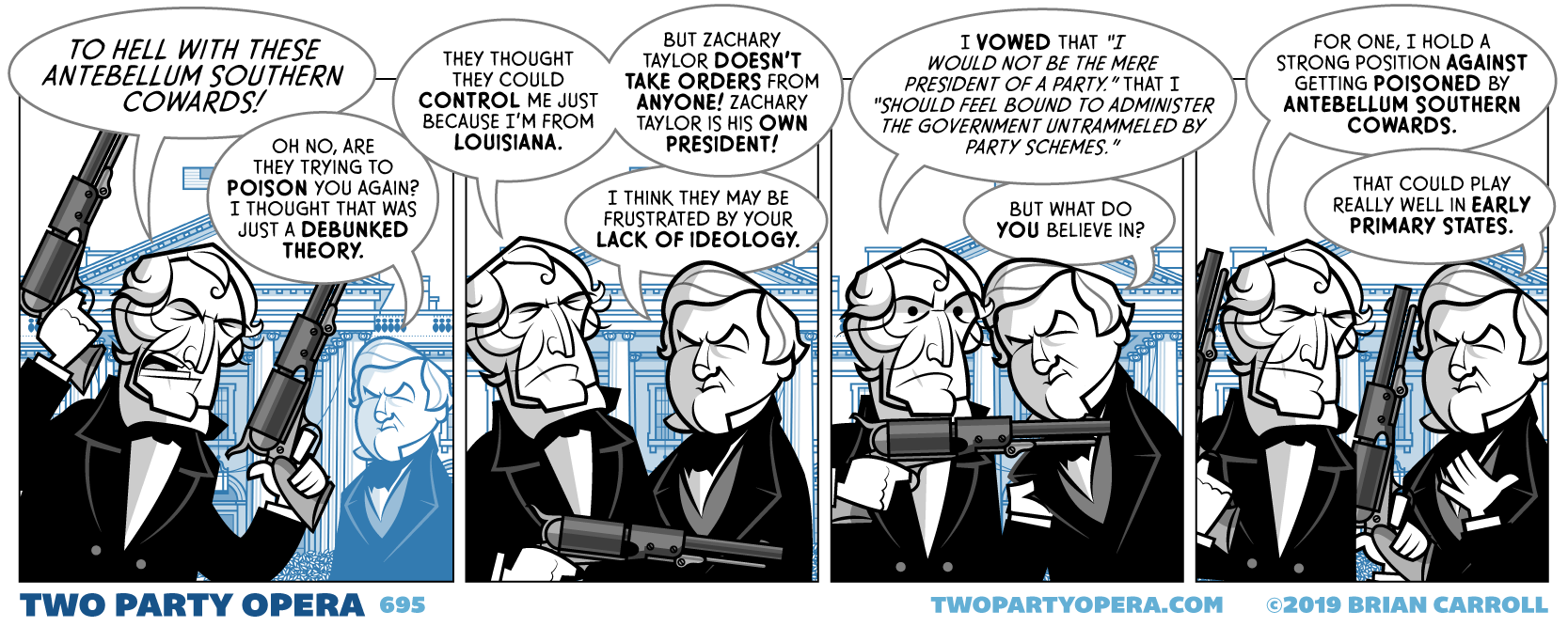

For someone who had been apolitical for most of his career, it should have been a surprise to no one that his supporters had projected their own politics onto him and not what he actually believed. He ignored most of the Whig Party platform, but conversely, the Southerners who voted for him because they assumed that as a slave-holding Southerner he would be pro-slavery were also disappointed.

The big issues facing his administration were California and New Mexico, and more generally, slavery. Every new state was a political landmine, and Taylor tried to be even-handed, but when push came to shove and Southerners started making noises about secession in earnest, he took a page from Andrew Jackson and threatened to lead troops and hang the secessionists if it came to that, thus revealing that in a choice between slavery and the Union, he'd pick the Union.

While Henry Clay began putting together what would eventually become the Compromise of 1850, Taylor was also dealing with the embarrassing Galphin Affair, in which his Secretary of War who had been representing an old claim dating back to the American Revolution got the claim, and payment for it by the federal government, approved by the Secretary of the Treasury, coincidentally netting him an enormous fee ($100,000 in 1850 dollars!) as well. All of these conflicts were bruising for his health and morale.

On July 4, 1850, he took a stroll around Washington, and ate a lot of cherries and iced milk. He abruptly took ill, suffering gastrointestinal distress that, over the next few days, turned fatal.

I am about to die - I expect the summons soon - I have endeavored to discharge all my official duties faithfully. I regret nothing, but am sorry that I am about to leave my friends.

As with many deaths in the 19th century, the exact cause of his death is a small mystery, about which historians can only speculate given the medical evidence available. At the time, of course, conspiracy theories sprang up with various factions accused of poisoning him. (An exhumation in the 1990s supposedly ruled out arsenic poisoning but not much else.)

The second POTUS to die in office left his Vice President, Millard Fillmore, as the country's second "accidental president."

The Biography

Most biographers like their subjects, probably an inevitable outcome of spending so much time getting to know them. Eisenhower's claim that Taylor could have prevented the Civil War is in fact fairly restrained and speculative. His argument is essentially that Taylor, being a Southerner himself, was able to speak to the Southerners in their language and appreciate their concerns, but at the same time, demonstrated he was willing to proactively shut down any talk of secession, even to the point of threatening to lead troops into New Mexico when Texas was threatening to take it. He was against the expansion of slavery, though he was making no moves to end it. Eisenhower thus speculates that if he had lived, Taylor might have seized control of the debate and kept the Union together. However, he also admits that it might just have moved the date at which the inevitable rupture would start.

Eisenhower is not entirely uncritical of Taylor. His description of Taylor's performance as a military commander is lukewarm; while Taylor was a hero to his men and the American public, Eisenhower points out several battles, during the Seminole and Black Hawk wars and again during the Mexican-American war, where, Taylor's tactics were, as Eisenhower tactfully puts it, "open to debate." He's fairly forgiving of Taylor's ambiguity on political issues, but admits that he determinedly avoided taking a stand and made his positions hard to decipher.

As Eisenhower himself points out, sometimes presidents are judged more by the significance of the events while they were in office than by their own significance. Zachary Taylor fought in a very significant war but not much important happened while he was president. That makes him mostly a historical footnote, and no one who isn't studying that time period deeply is likely to read a very long book about a mediocre president who only served for sixteen months. That makes this fairly brief volume large enough to cover all the important details and give us a picture of the man and why he's important to history, despite his relatively inconsequential administration, without spending too much time on him.

My complete list of book reviews.

Times Books, 2008, 192 pages

The rough-hewn general who rose to the nation's highest office, and whose presidency witnessed the first political skirmishes that would lead to the Civil War.

Zachary Taylor was a soldier's soldier, a man who lived up to his nickname, "Old Rough and Ready." Having risen through the ranks of the U.S. Army, he achieved his greatest success in the Mexican War, propelling him to the nation's highest office in the election of 1848. He was the first man to have been elected president without having held a lower political office.

John S. D. Eisenhower, the son of another soldier-president, shows how Taylor rose to the presidency, where he confronted the most contentious political issue of his age: slavery. The political storm reached a crescendo in 1849, when California, newly populated after the Gold Rush, applied for statehood with an anti- slavery constitution, an event that upset the delicate balance of slave and free states and pushed both sides to the brink. As the acrimonious debate intensified, Taylor stood his ground in favor of California's admission-despite being a slaveholder himself-but in July 1850 he unexpectedly took ill, and within a week he was dead. His truncated presidency had exposed the fateful rift that would soon tear the country apart.

Slogging through the biographies of presidents leading up to the Civil War is like reading prequel novels: they're full of interesting characters and background details in a story whose ending you already know. In a sense this is true of any history book, but until the war, there was an almost endearing belief by everyone, North and South, that we'll somehow find a resolution and hold the country together. As names like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis begin to join that upstart congressman from Illinois on the stage, there is a sense of inevitable futility in their projects.

Zachary Taylor was the second president to die in office, only sixteen months into his term. Unlike William Henry Harrison, the first POTUS to die in office, he at least had some time to be president, but at the time of his sudden illness and death, his administration had not done much, and his only real accomplishment as president was signing the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, which settled tensions between Britain and the United States over Central America and the future Panama Canal.

So I was intrigued by the thesis presented in this book's introduction, that the almost unremembered twelfth president might have prevented the Civil War had he lived. The author of this biography, John S.D. Eisenhower, was the son of President Dwight Eisenhower, so presumably he knew a few things about presidents. (John Eisenhower had a pretty distinguished career of his own and later became a military historian.)

Yet Another Virginian Slaveholder

A common thread through most early presidential biographies is the preeminence of Virginia as, at one time, probably the most influential state in the union, and how many presidents came from there. Taylor was born in Virginia in 1784, though he grew up in Kentucky and owned plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana. Like so many of his peers, though, he was one of those men who viewed slavery as a sort of necessary evil that he would have preferred didn't exist, while still benefiting from it. As a military officer in the field for most of his life, he probably had little direct interaction with slaves. But the fact that he was a slave owner who was secretly against expanding slavery would become very significant when he became president, and is probably the reason for Eisenhower's judgment that he could possibly have steered the country away from a war over slavery.

Old Rough and Ready

Like many undistinguished presidents, even those who survived their term in office, Zachary Taylor's life and career before becoming president is more interesting than his presidency. He was a military man for most of his life, with a career that began during the War of 1812 and continued through the Mexican-American War, during which he was simultaneously one of the two commanding generals over American forces and a nascent presidential candidate.

Taylor's life and career in many ways paralleled that of his mentor, William Henry Harrison. Harrison praised Taylor's performance during the War of 1812. Like Harrison, Taylor spent most of the war fighting Indians in the interior. Taylor continued to make his reputation as an Indian fighter, leading American forces in the Black Hawk and Seminole wars. He acquired the nickname "Old Rough and Ready" during this time, for being the kind of officer who rode and camped and fought with his troops and shared all of their hardships.

My daughter will never marry a soldier!

Taylor's wife was Margaret "Peggy" née Smith, described by multiple sources as "fat and motherly." She suffered greatly from her husband's frequent campaigns, as well as multiple childbirths. She was a semi-invalid and supposedly promised God to remain a recluse if her husband came home safely from his various campaigns. She evidently kept this promise, as when Taylor became President, the unwilling First Lady (she actually prayed for her husband to lose the election) remained secluded on the second floor of the White House and let her daughter take on the role of hostess.

There are not a lot of details about Taylor's personal life and habits in this book, probably because while Taylor did write letters, he wasn't highly educated or philosophical, and much of his correspondence was stored in his son's house in Baton Rouge, which was burned by the Union Army during the Civil War. But generally, he seems to have been a plain, honest, and unsophisticated (not to say unintelligent) man who mostly enjoyed being a soldier but also recognized what a hard life it was, especially for his family. Long periods of separation from his wife made them both unhappy, so he became extremely determined not to allow his daughter to marry a military man and suffer the same hardships.

This led to a story as old as time: his 18-year-old daughter Sarah fell in love with an officer, and forbidden by her father to see him, the two lovers conspired to meet anyway, and eventually married, without her father's blessing or attendance.

That officer's name? Jefferson Davis.

Taylor and Davis were estranged after this, even after (or because of) Sarah's untimely death, which left both her father and her widowed husband devastated. Eventually, however, Taylor and Davis would reconcile, when Davis (along with many other future Confederate leaders such as Robert E. Lee ) would serve under him during the Mexican-American War.

The Mexican-American War

At first the Mexicans showed little hostility. In the afternoon, in fact, a group of young women emerged from behind the line of sentries and came down the bank of the river. They disrobed in front of the spectators on both sides and plunged into the water for a swim. A few American officers who were already in the river swam toward them. The Mexican sentries on the opposite bank let the Americans reach almost to the middle before letting it be known that they were to go no farther. The young officers blew kisses to the tawny damsels, who laughed and returned the compliments. Both groups then swam back to their respective shores.

Despite this light-hearted beginning, the Mexican-American War was a bloody affair that was as political as it was military, and while Eisenhower goes into some detail on both the diplomacy and the battles, the main significance for Taylor is that it made him a national figure and presidential candidate, while also hardening the mutual dislike between himself and President Polk.

Polk had initially chosen Taylor over General Winfield Scott to command American troops in Mexico because Scott was a Whig whereas Taylor had until that point appeared relatively apolitical. However, Taylor had often been unhappy at the commands he was given, and he felt slighted by a decision from Polk regarding the precedence of regular ranks over brevet ranks. (Taylor had been given the brevet rank of Major General.) After Taylor captured Monterrey, he more or less ignored Polk's wishes and signed a temporary truce with the Mexican general, allowing him to withdraw most of his troops. Polk sent Winfield Scott to take most of Taylor's troops, which may have backfired, as Taylor then had to fight General Santa Anna with a much smaller force. Outnumbered about three to one, the Americans inflicted far greater casualties against the Mexican forces at the Battle of Buena Vista. After Santa Anna withdrew, both sides claimed victory, but combined with General Scott's landing at Veracruz, these two battles more or less ended the war. The Battle of Buena Vista overshadowed Scott's clear triumph at Veracruz (perhaps because of numerous tragic losses, such as the son of Senator Henry Clay), and Taylor became a bonafide national hero.

The Election of 1848

"It has never entered my head, nor is it likely to enter the head of any other person."

Prior to becoming a presidential nominee, Zachary Taylor had spent most of his life avoiding politics, to the point that he didn't even vote. He wasn't lacking in ambition, but his ambitions had mostly concerned climbing the ranks in the Army. It seems to have been in large part a desire not to serve under a president he'd grown to dislike (James Polk) that turned him political.

Taylor-for-President clubs had already started while he was still in Mexico, but his nomination seems to have come about as almost unplanned and unanticipated by everyone including himself. He was being courted by both the Democrats and Whigs while refusing to align himself with either party, until finally in early 1848 he was persuaded to declare himself for the Whigs.

His rivals for the Whig nomination were his frenemies General Winfield Scott and perpetual presidential candidate Henry Clay, but the Whigs eventually decided to go with what had worked last time and nominated the war hero, making Taylor the second former general to become a Whig President. Unfortunately, William Henry Harrison would prove to be another precedent for Taylor.

Since Polk was keeping his promise not to run for reelection, Taylor faced Lewis Cass for the Democrats and in one of the most remarkable heel turns in American history, a third-party bid by former President Martin Van Buren and Charles Adams (son of John Quincy Adams), who had started the Free Soil Party. He captured a majority of electoral votes and a plurality of the popular vote, and would be the last president elected before the Republican/Democrat two-party system would control American politics forever after.

The Curse of Whig Generals

Taylor was technically still a commissioned officer when he was elected president, which made for an awkward few months for his commanding officer and former rival, General Winfield Scott.

As a president, Zachary Taylor was unremarkable, and not just because he died early. James Polk, who received him courteously enough when he arrived in Washington, judged him to be crude and almost illiterate (not really true).

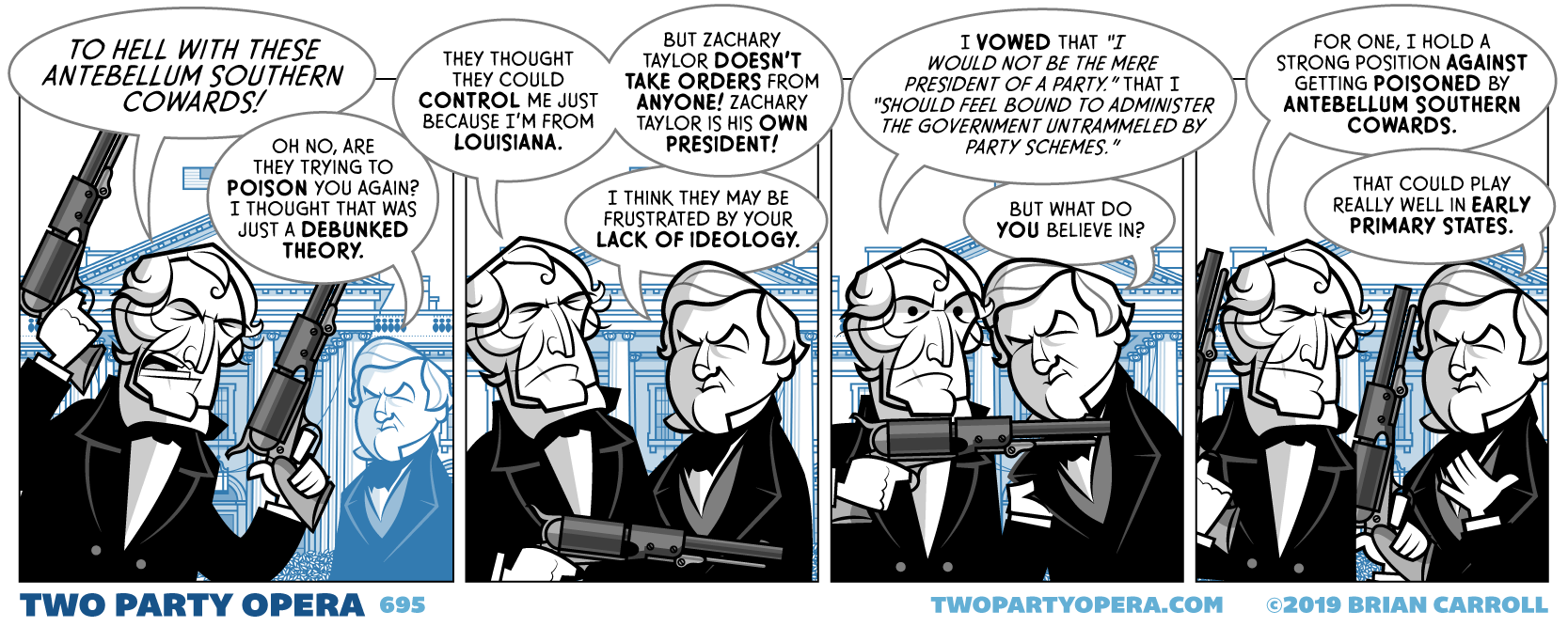

For someone who had been apolitical for most of his career, it should have been a surprise to no one that his supporters had projected their own politics onto him and not what he actually believed. He ignored most of the Whig Party platform, but conversely, the Southerners who voted for him because they assumed that as a slave-holding Southerner he would be pro-slavery were also disappointed.

The big issues facing his administration were California and New Mexico, and more generally, slavery. Every new state was a political landmine, and Taylor tried to be even-handed, but when push came to shove and Southerners started making noises about secession in earnest, he took a page from Andrew Jackson and threatened to lead troops and hang the secessionists if it came to that, thus revealing that in a choice between slavery and the Union, he'd pick the Union.

While Henry Clay began putting together what would eventually become the Compromise of 1850, Taylor was also dealing with the embarrassing Galphin Affair, in which his Secretary of War who had been representing an old claim dating back to the American Revolution got the claim, and payment for it by the federal government, approved by the Secretary of the Treasury, coincidentally netting him an enormous fee ($100,000 in 1850 dollars!) as well. All of these conflicts were bruising for his health and morale.

On July 4, 1850, he took a stroll around Washington, and ate a lot of cherries and iced milk. He abruptly took ill, suffering gastrointestinal distress that, over the next few days, turned fatal.

I am about to die - I expect the summons soon - I have endeavored to discharge all my official duties faithfully. I regret nothing, but am sorry that I am about to leave my friends.

As with many deaths in the 19th century, the exact cause of his death is a small mystery, about which historians can only speculate given the medical evidence available. At the time, of course, conspiracy theories sprang up with various factions accused of poisoning him. (An exhumation in the 1990s supposedly ruled out arsenic poisoning but not much else.)

The second POTUS to die in office left his Vice President, Millard Fillmore, as the country's second "accidental president."

The Biography

Most biographers like their subjects, probably an inevitable outcome of spending so much time getting to know them. Eisenhower's claim that Taylor could have prevented the Civil War is in fact fairly restrained and speculative. His argument is essentially that Taylor, being a Southerner himself, was able to speak to the Southerners in their language and appreciate their concerns, but at the same time, demonstrated he was willing to proactively shut down any talk of secession, even to the point of threatening to lead troops into New Mexico when Texas was threatening to take it. He was against the expansion of slavery, though he was making no moves to end it. Eisenhower thus speculates that if he had lived, Taylor might have seized control of the debate and kept the Union together. However, he also admits that it might just have moved the date at which the inevitable rupture would start.

Eisenhower is not entirely uncritical of Taylor. His description of Taylor's performance as a military commander is lukewarm; while Taylor was a hero to his men and the American public, Eisenhower points out several battles, during the Seminole and Black Hawk wars and again during the Mexican-American war, where, Taylor's tactics were, as Eisenhower tactfully puts it, "open to debate." He's fairly forgiving of Taylor's ambiguity on political issues, but admits that he determinedly avoided taking a stand and made his positions hard to decipher.

As Eisenhower himself points out, sometimes presidents are judged more by the significance of the events while they were in office than by their own significance. Zachary Taylor fought in a very significant war but not much important happened while he was president. That makes him mostly a historical footnote, and no one who isn't studying that time period deeply is likely to read a very long book about a mediocre president who only served for sixteen months. That makes this fairly brief volume large enough to cover all the important details and give us a picture of the man and why he's important to history, despite his relatively inconsequential administration, without spending too much time on him.

My complete list of book reviews.