Book Review: Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, by Richard Wrangham

One-line summary: Presents the thesis that control of fire was not merely a side effect of our evolution, but an essential component of it; humans have evolved to eat cooked food.

Reviews:

Goodreads: Average: 3.65. Mode: 4 stars.

Amazon: Average: 4.1. Mode: 5 stars.

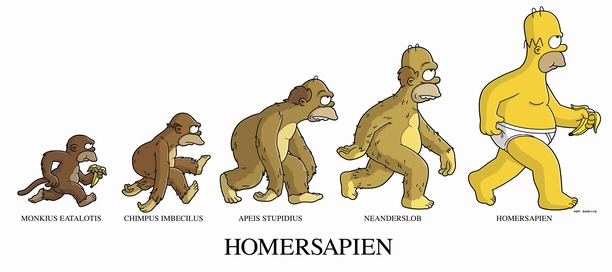

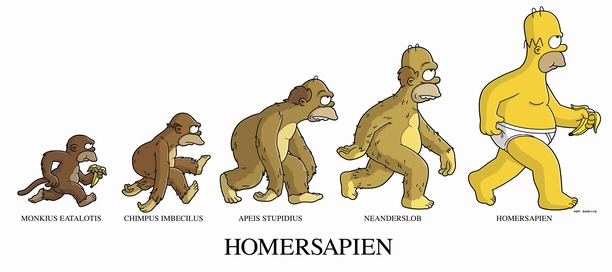

Until two million years ago, our ancestors were apelike beings the size of chimpanzees. Then Homo erectus was born and we became human. What caused this extraordinary transformation?

In this stunningly original book, renowned primatologist Richard Wrangham argues that cooking created the human race. At the heart of Catching Fire lies an explosive new idea: The habit of eating cooked rather than raw food permitted the digestive tract to shrink and the human brain to grow, helped structure human society, and created the male-female division of labor. As our ancestors adapted to using fire, humans emerged as “the cooking apes.”

A groundbreaking new theory of evolution, Catching Fire offers a startlingly original argument about how we came to be the social, intelligent, and sexual species we are today

Everyone knows that the "discovery" of fire was one of the most important leaps forward in human technological and cultural evolution. Before that, we were naked apes huddling frightened in caves. Once we had fire, we could start making tools that were more than sharp rocks and pointy sticks. We started being able to consistently punch above our weight class and pretty much dominate every other living thing out there. No more running from sabertooths, no more looking at an elephant and thinking, "Well, yeah, it probably would be tasty but it's just too damn big!"

But fire came along after we were already smart enough to use it. Fire was awfully useful and fortuitous for us, but we didn't need it to evolve as a species, right?

Not so, says Richard Wrangham. In fact, without fire, we would still be apes, literally. His thesis is that modern humans are, in fact, evolutionarily adapted to eat cooked food, that our ancestors' ability to control fire is what led to this adaptation, and that without it, we'd never have become the tool-using, city-building, civilization-having donut-eating naked apes we are today.

He makes a very persuasive case. Your first objection may be (as mine was): "But evolution takes a long time, and control of fire is relatively recent in our history. How could we have evolved as fire-users and cooked food-eaters?"

Wrangham makes two arguments: first, that speciation (evolution from one species into another distinctly different species) has been shown to take as little as 15,000 years. Second, that there is convincing evidence that humans were using fire consistently at least 200,000 years ago, and some evidence (though less convincing) that at least some groups of human ancestors were using it over 700,000 years ago.

If this is the case, then it is certainly possible that early hominids gaining control of fire and using it to cook food could have affected their subsequent evolution. But what other evidence is there?

From here, Wrangham goes into a lot of physical anthropology, talking mostly about Australopithicenes (our early ancestors) and Homo habilis (the so-called "missing link"). He presents a fair amount of physical evidence, both using what we know about these species and by comparing them with ape and monkey species, that the latter had a diet consisting largely of cooked food -- unlike Australopithicenes, Homo habilis used fire.

How would this affect our evolution? In a nutshell, cooked food is easier to chew and digest and provides a higher yield in nutrients. In other words, you get more calories for less effort, providing a critical evolutionary advantage when calories are often hard to come by. Also, fewer hours in the day spent collecting food and chewing it (monkeys literally spend many hours out of each day just chewing their food enough that it can be digested) means more hours that can be spent figuring out more effective ways to kill things with pointy objects -- thus, technological advancement. (I am of course simplifying a lot here.)

There is a lot of food science talk here, and discussions of macronutrients and the process of digestion and relative brain and intestinal mass. The arguments for cooked food being more nutritious (as well as making many more foods available, food that would be almost impossible to digest and even poisonous without cooking it first) are incontrovertible. However, Wrangham's thesis that therefore humans evolved to eat cooked food is certainly not yet universally accepted. Raw foodists and those who advocate the so-called Paleolothic diet will of course dispute the claim that cooked food made up the bulk of our Paleolithic ancestors' diet. Vegans also aren't going to be too happy about Wrangham's conclusions -- but then, in my experience, few vegans will admit that a healthy vegan diet is essentially impossible without a modern agricultural-industrial network. Interestingly, there are no vegans or raw foodists among pre-industrial societies. Every known human society has added meat to their diet when it was available, and also used fire to cook it. And, in fact, so do chimpanzees. Wrangham describes a number of primate studies showing that apes and monkeys, when given a choice between raw food or cooked food, almost always prefer the cooked version.

In the second half of the book, Wrangham moves away from evolutionary biology and into evolutionary psychology. This usually flashes a big red warning sign in my head, since I read very little pop science evpsych that isn't a crock of shit. To his credit, most of Wrangham's arguments here are reasonable, though (naturally, since it's evpsych) far more speculative and unsubstantiated. He examines many "primitive" human cultures and the role that cooking has played in them, and tries to come up with theories for how cooking would have provided an evolutionary advantage to humans once we were doing it regularly. Although his theories are mostly reasonable, they also seem unnecessary in light of the earlier biological arguments. Also, while he comes to the grim conclusion that cooking essentially led to patriarchy, as it tied women to the homemaker role, I think he misses some obvious conclusions by doing what most evpsychers do in treating females as basically an evolutionary "resource" to explain why males are the way they are: in his discussion, women are like fire and shelter and food, just something men use to gain a reproductive advantage. For example, he observes that men in most societies find it relatively easy to find sexual partners, but not as easy to find a live-in cook (i.e., wife). He explains this entirely in terms of how women who can be tied to hearth and home and kids are a valuable resource. It apparently does not occur to him that maybe it's because women are active agents in the process, and just like men, enjoy sex more than they enjoy cooking. ("Have sex with you? Sure. Umm, spend the rest of my life cooking your meals and washing your dishes? Let me think on that...")

While I found the sociological arguments less convincing, especially when they tried to extrapolate from the behavior of monkeys and apes to humans, I believe that the physical science arguments based on nutrition and evolutionary biology were solid. Raw foodists will have their work cut out for them to refute Wrangham's thesis and convince us that we should all go back to eating uncooked leaves and seeds. And while there may be ethical and environmental arguments against eating meat (for those humans privileged enough to be able to live on a meatless diet), the physical evidence runs overwhelmingly against the theory that humans were meant to be vegans or even vegetarians.

Verdict: Recommended for anyone with an interest in evolution and/or food science. Wrangham's thesis is revolutionary, but not in a crackpot "This changes everything we thought we knew" way. Rather, it challenges some basic assumptions about how we evolved without denying any of the existing evidence. His arguments are mostly quite strong, and while to my knowledge, some anthropologists have challenged his assumptions about when humans started using fire, there have not yet been any serious challenges to his conclusions from an evolutionary perspective.

Reviews:

Goodreads: Average: 3.65. Mode: 4 stars.

Amazon: Average: 4.1. Mode: 5 stars.

Until two million years ago, our ancestors were apelike beings the size of chimpanzees. Then Homo erectus was born and we became human. What caused this extraordinary transformation?

In this stunningly original book, renowned primatologist Richard Wrangham argues that cooking created the human race. At the heart of Catching Fire lies an explosive new idea: The habit of eating cooked rather than raw food permitted the digestive tract to shrink and the human brain to grow, helped structure human society, and created the male-female division of labor. As our ancestors adapted to using fire, humans emerged as “the cooking apes.”

A groundbreaking new theory of evolution, Catching Fire offers a startlingly original argument about how we came to be the social, intelligent, and sexual species we are today

Everyone knows that the "discovery" of fire was one of the most important leaps forward in human technological and cultural evolution. Before that, we were naked apes huddling frightened in caves. Once we had fire, we could start making tools that were more than sharp rocks and pointy sticks. We started being able to consistently punch above our weight class and pretty much dominate every other living thing out there. No more running from sabertooths, no more looking at an elephant and thinking, "Well, yeah, it probably would be tasty but it's just too damn big!"

But fire came along after we were already smart enough to use it. Fire was awfully useful and fortuitous for us, but we didn't need it to evolve as a species, right?

Not so, says Richard Wrangham. In fact, without fire, we would still be apes, literally. His thesis is that modern humans are, in fact, evolutionarily adapted to eat cooked food, that our ancestors' ability to control fire is what led to this adaptation, and that without it, we'd never have become the tool-using, city-building, civilization-having donut-eating naked apes we are today.

He makes a very persuasive case. Your first objection may be (as mine was): "But evolution takes a long time, and control of fire is relatively recent in our history. How could we have evolved as fire-users and cooked food-eaters?"

Wrangham makes two arguments: first, that speciation (evolution from one species into another distinctly different species) has been shown to take as little as 15,000 years. Second, that there is convincing evidence that humans were using fire consistently at least 200,000 years ago, and some evidence (though less convincing) that at least some groups of human ancestors were using it over 700,000 years ago.

If this is the case, then it is certainly possible that early hominids gaining control of fire and using it to cook food could have affected their subsequent evolution. But what other evidence is there?

From here, Wrangham goes into a lot of physical anthropology, talking mostly about Australopithicenes (our early ancestors) and Homo habilis (the so-called "missing link"). He presents a fair amount of physical evidence, both using what we know about these species and by comparing them with ape and monkey species, that the latter had a diet consisting largely of cooked food -- unlike Australopithicenes, Homo habilis used fire.

How would this affect our evolution? In a nutshell, cooked food is easier to chew and digest and provides a higher yield in nutrients. In other words, you get more calories for less effort, providing a critical evolutionary advantage when calories are often hard to come by. Also, fewer hours in the day spent collecting food and chewing it (monkeys literally spend many hours out of each day just chewing their food enough that it can be digested) means more hours that can be spent figuring out more effective ways to kill things with pointy objects -- thus, technological advancement. (I am of course simplifying a lot here.)

There is a lot of food science talk here, and discussions of macronutrients and the process of digestion and relative brain and intestinal mass. The arguments for cooked food being more nutritious (as well as making many more foods available, food that would be almost impossible to digest and even poisonous without cooking it first) are incontrovertible. However, Wrangham's thesis that therefore humans evolved to eat cooked food is certainly not yet universally accepted. Raw foodists and those who advocate the so-called Paleolothic diet will of course dispute the claim that cooked food made up the bulk of our Paleolithic ancestors' diet. Vegans also aren't going to be too happy about Wrangham's conclusions -- but then, in my experience, few vegans will admit that a healthy vegan diet is essentially impossible without a modern agricultural-industrial network. Interestingly, there are no vegans or raw foodists among pre-industrial societies. Every known human society has added meat to their diet when it was available, and also used fire to cook it. And, in fact, so do chimpanzees. Wrangham describes a number of primate studies showing that apes and monkeys, when given a choice between raw food or cooked food, almost always prefer the cooked version.

In the second half of the book, Wrangham moves away from evolutionary biology and into evolutionary psychology. This usually flashes a big red warning sign in my head, since I read very little pop science evpsych that isn't a crock of shit. To his credit, most of Wrangham's arguments here are reasonable, though (naturally, since it's evpsych) far more speculative and unsubstantiated. He examines many "primitive" human cultures and the role that cooking has played in them, and tries to come up with theories for how cooking would have provided an evolutionary advantage to humans once we were doing it regularly. Although his theories are mostly reasonable, they also seem unnecessary in light of the earlier biological arguments. Also, while he comes to the grim conclusion that cooking essentially led to patriarchy, as it tied women to the homemaker role, I think he misses some obvious conclusions by doing what most evpsychers do in treating females as basically an evolutionary "resource" to explain why males are the way they are: in his discussion, women are like fire and shelter and food, just something men use to gain a reproductive advantage. For example, he observes that men in most societies find it relatively easy to find sexual partners, but not as easy to find a live-in cook (i.e., wife). He explains this entirely in terms of how women who can be tied to hearth and home and kids are a valuable resource. It apparently does not occur to him that maybe it's because women are active agents in the process, and just like men, enjoy sex more than they enjoy cooking. ("Have sex with you? Sure. Umm, spend the rest of my life cooking your meals and washing your dishes? Let me think on that...")

While I found the sociological arguments less convincing, especially when they tried to extrapolate from the behavior of monkeys and apes to humans, I believe that the physical science arguments based on nutrition and evolutionary biology were solid. Raw foodists will have their work cut out for them to refute Wrangham's thesis and convince us that we should all go back to eating uncooked leaves and seeds. And while there may be ethical and environmental arguments against eating meat (for those humans privileged enough to be able to live on a meatless diet), the physical evidence runs overwhelmingly against the theory that humans were meant to be vegans or even vegetarians.

Verdict: Recommended for anyone with an interest in evolution and/or food science. Wrangham's thesis is revolutionary, but not in a crackpot "This changes everything we thought we knew" way. Rather, it challenges some basic assumptions about how we evolved without denying any of the existing evidence. His arguments are mostly quite strong, and while to my knowledge, some anthropologists have challenged his assumptions about when humans started using fire, there have not yet been any serious challenges to his conclusions from an evolutionary perspective.