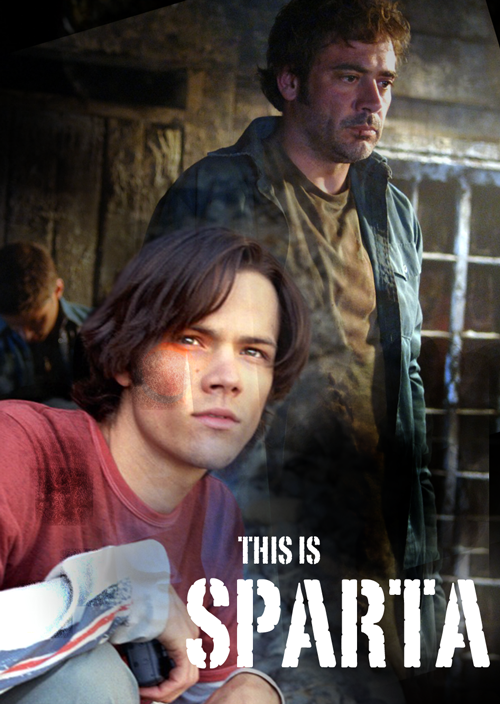

This is Sparta - Part One (1 of 2)

(Title Artwork Courtesy of the VERY talented

sheaseth!)

Sam sat on the top step of the cabin, looking out the long, white road, watching the dust settle through the hot, green trees as the Impala barreled away towards Atlanta. With his arms wrapped around his knees, he rocked a little bit, feeling the heat through his thin cutoffs and t-shirt, both hand-me-downs from Dean, and already sticking to him, though it was only 9 in the morning. Mentone, Alabama, was not the armpit of the mountain country, but the way he figured it, the small cabin two miles out of town, just along the ridge where the water of the river cut deep through the rocks, was.

He had until the afternoon to get his chores done, but seeing as it was going to get hotter than it already was well before noon, he knew he should get started. There was cutting wood to pay rent to the cabin’s owner, a man Dad knew, dishes, for crying out loud, and then he had to oil the guns. Dean and Dad had cleaned them inside and out, his job was to wipe them down with a last coat of oil and lay them out for inspection. To answer questions about them, like a test. It was, he had overheard Dad say, to familiarize him with how they felt. Their weight and heft. Cold iron. Then when Dad and Dean got back with the new crossbow, they were going to start training.

Standing up, he knew it was best to get started, but the sweat ran across his skin with just that motion alone, and it was going to be a whacked out summer even before it started. Didn’t seem to matter that he’d been on the team that had won the 6th grade division. Didn’t matter that he’d won a trophy, for Pete’s sake. Nothing Sam had done or said had kept Dad from packing them up and leaving the little town of Greeley, where Sam had felt his feet putting down roots. Okay, so he couldn’t go to soccer camp, he understood that. But the rec center just down the street had been offering soccer matches for kids three times a week. At only a dollar a time. That had seemed doable, but not to Dad.

Training. That was what Dad wanted for his boys. Daily runs. Guns. Shooting. Knife work. Latin. More running. All summer. Some sort of test at the end of it all. And the blasted crossbow. Dean was out of his mind with joy at the prospect, actually talking in bed three nights running before Sam had pulled a pillow over his head and Dean had taken the hint. He was glad for Dean, sure, but Sam didn’t like the look in Dad’s eye. It had been hard since they’d arrived three days ago, like he was chafing at their need to get groceries and settle in. To figure out to work the hot water heater each and every time they needed hot water. How to work the backup generator, since the trees were known to down power lines in a high wind. How to keep mold from growing in sneakers or damp rags left in a clump in a cabin with no air conditioner. Pine Sol and a drying line, Dad had figured. Sam was already sick of the smell. And the need to hang every single thing out to dry.

He wiped his hands on the back of his shorts, and decided that cutting wood should come first. Then dishes. Then oiling. Handling the guns was his least favorite, he would leave that till last.

*

Blisters. He had three of them all lined up at the bottom of his fingers, swelling under the pads and threatening to burst. Then, when he was doing the dishes, they did, letting in the soapy water like battery acid. He jerked his hands out of the sink and swore. It took him cold water and doing the dishes mostly with his left hand before the stinging settled down. At least he was almost done, and it was the afternoon, and Dad and Dean would be home soon. Although that wouldn’t be a huge improvement, because the second they did, Dean would be hopping with excitement to get started with the crossbow. And Dad would be right there with him, going over the damn thing like they’d never bought a new weapon in their lives. Checking it out, testing it, planning the training around it. Bow hunting had been bad enough, and Sam’s skin could still remember the welts from the damn bowstring hitting the inside of his elbow. Dad had told him to tough it out; it had been Dean who’d showed him how to rotate his elbow out of the way.

The heat in the house had finally stabilized by the time he started in on the guns, and a cross breeze had picked up. He opened all the windows, and allowed himself a glass of water and a banana, already starting to get brown, and laid some newspapers out on the table. He checked to make sure the guns were unloaded and put them all in a row. They gleamed up at him, almost dull, like their eyes were closed. Then he got the gun oil, and opened it. The smell was familiar, like cooking oil, only cold. Dusty, almost. Getting a rag just a little damp with the oil, he wiped them all down. The Glock, the Taurus, Dean’s 1911, and the rest of them. Then he wiped down the rifles, one at a time, making sure not to get any gun oil on the wooden stocks.

It was hard to hold each rifle upright, and not rest the muzzle against anything, and then rub it down. His arms got tired halfway through each one, but he recited the names to himself as he rested. Winchester 1897, Winchester Carbine, M16, and then the Yellowboy. That’s when his fingers, slick with oil, dropped the rifle to the floor. Not loaded, it didn’t go off, but the stock was cracked straight through up to the plate. He picked it up, his thumb tracing the crack. It was ruined. And outside, along the breeze, far down the road, he heard the rumble of the Impala.

It was almost like fists suddenly clenched themselves in his stomach. He hadn’t wanted to clean the stupid guns in the first place. He didn't want to train. He didn’t even want to be here, and yet here he was. Standing in a backwoods cabin, gun oil all up and down his front, a broken rifle in his hands, and his Dad on the way. He was going to get it, there was no getting around it. And Dad’s whippings hurt.

Without thinking, he hurried over to the leather couch and shoved the rifle all the way under the cushions, pushing till his fingers hit the wooden frame. Then he straightened everything and hurried back to the kitchen tables where the rifles waited. Heart beating against his breastbone like a bird trying to get out. He moved the hair out of his eyes with his forearms and stacked the rifles up against the kitchen table. Slowly put the cap back on the container of gun oil, and folded the greasy rag on top of that. Turned to face the door as the Impala pulled up in the dirt in front of the cabin.

He was washing his hands when the door opened, Dean and Dad’s boots thumping on the wooden floor, the thumping echoing in his stomach. It wasn’t going to work. Dad could count, he would see that one of the rifles was missing. Sam stepped away from the sink reaching out like he meant to point to the couch and confess, but Dean shoved a box in his hand.

“More supplies,” he said, voice bright and happy.

He was covered in dust from the road and sweat from the day stuck his shirt to him, but his eyes were like shiny green stones. Sam took the box.

“Put that away, Sammy, and then help us unload the car.”

Sam looked up. Dad was standing by the doorway, dusty like Dean, with sweat under his armpits. Dad hadn’t shaved that morning, so his five o’clock shadow looked hard, and he wasn’t smiling. Which didn’t surprise Sam any, seeing as how focused he was in that this summer should be extremely productive. Might have something to do with Dean turning sixteen next winter, and Dad’s plans that Dean should start hunting like a man. You couldn’t throw an untrained kid into that, even Sam was aware of how dangerous that could be. John’s seriousness about the whole matter just made it even that more scary, though Dean seemed to feel the whole thing was a lark. And he wanted it. Wanted it more than anything. Except maybe the Impala.

Sam turned, not saying anything to his Dad’s not saying anything, and put the box on the narrow counter and opened it up. First aid supplies. Batteries. More gun oil. He sighed. And started unloading the box. And then the next one. And the bags after that. And finally, just as he’d known it would, in came the crossbow. Black, shiny, and looking a whole lot like a sawed off shotgun with a bow at one end. Dean came in with it cradled in his arms like a baby, a dangerous baby that could kill a man silently at fifty feet.

“Look, Sammy,” he said, bringing it closer, his voice lowered as if he was in church. “Look.”

Sam reached out to touch it with one finger, and for a moment it looked as though Dean was going to jerk the crossbow out of his reach. Rather like he thought Sammy would ruin it that way. But he held still, and when Sam’s skin touched the side of the stock, it felt cold. Dead.

“It pulls seventy pounds,” said Dean.

Sam knew that was a lot more than Dean’d been pulling with the conventional bow they used last summer. He himself had been pulling 20 pounds, which was, according to Dean, a baby’s bow. He’d often joked if Sam wanted baby arrows to go with that until Dad had told him to knock it off.

Dad came in. “Put that away, Dean. Chores.”

Dean put the crossbow lovingly away on the top of the fridge as Dad walked to the kitchen table and took in the fruits of Sam’s efforts for the day. With his eyes he looked at the guns, and then the rifles. Then he asked, “How much wood?”

“Uh,” said Sam, trying not to wipe his hands on his cutoffs and failing. “I don’t know. Two bundles?’

Dad’s reply was a low voiced sigh, as if that was what he expected from his youngest and was trying not to be disappointed.

“Okay,” he said. Not approval, but dismissal. “Put these away. I’ll make dinner.”

Holding out his hand, Sam took the keys to the Impala, and placed the guns and the rifles one by one in the trunk. He was covered in dust by the time he was done, as the sun started setting through the trees and the onset of dusk brought the first cool breeze of the day. His heart still felt tight, but it was going to be okay. Once a rifle went into the trunk of the Impala, it would be like a black hole. Nobody would notice if one was missing. Then, when he got his chance, he would take the Yellowboy out and bury it in the woods. He gave the keys to the Impala back to Dad with as much calm as he could muster.

Dinner was chili out of a can and crackers and milk. And silent as they sat at the table, the wind from the open window blowing a little across their bowls. Afterwards, while Dean did the dishes, Sam ate a peach on the couch while Dad fiddled with the antenna on the TV. The picture came in fuzzy, but it felt more normal than it had all day.

“At least it’s in color,” said Dad, sinking back among the cushions, taking off his boots for the first time all day.

Sam nodded, hiding behind his peach. A huge part of his brain had forgotten that the couch was where Dad slept at night, but that was okay. He’d have to get rid of the rifle during the day, was all.

*

The cabin was small. There was only one bedroom, a long narrow bathroom, and the main room shaped like an L. At one end of the L was the kitchen, the table, the stove, and a long, chipped counter. At the other end of the L, near the front door, was the couch, where Dad slept, and the TV, which only got three channels, and all of them badly. The windows had been left open the night before, and on the fourth morning Sam got up, feeling the dampness on his sheets and pillow, and opened his eyes to see Dean, already awake. Getting up. Slipping yesterday’s clothes on, his shoes and socks, striding out of the room with a purpose and an eagerness that Sam couldn’t hope to match. Unless it were soccer he was going to, which it wasn’t likely to be, not in the near future, not ever.

Sam trailed after his brother, scratching his ribs, smelling eggs and bacon and trying not to frown. Only Dean knew how to make eggs the way Sam liked them. He was careful. He took out the stringy white cord, and then beat the eggs to a froth. If they had any, he would add milk and cheese, and then fry them up slowly. Dad? He didn’t take out the white thing, just cracked the eggs in the pan and stirred them a few times with his fork, making a mess of white and yellow so hard, Sam could barely get it down. As Sam walked up to the table and sat down with his back to the fridge, Dad came over with the cast iron pan, and scooped out a mess of eggs for each of them. And bacon as well, done nicely crisp, but the eggs. Sam stared at his plate, and reached for the pepper. If he put enough on, and ate everything fast, while it was hot, too hot to feel texture, he could get the eggs down. And then maybe Dad would make some fried bread to fill the corners of his stomach.

“Eat up, boys,” said Dad. He was smiling, so thus far hadn’t noticed Sam’s frown. He felt like he was frowning with his whole body. He hated eggs this way. Hated them. But Dean and Dad were shoveling them in, white bits and all. Sam tried. Within two minutes, he had to leap up to explode his last mouthful in the sink

“There he goes,” said Dean, the fork in his hand clinking against the plate. “Told you, Dad.”

“He’s got to learn,” said Dad, and Sam was glad he couldn’t see his father shoving eggs in his mouth. “Sometimes, you don’t get them the way you like them.”

Sam didn’t say anything. He could feel the sweat on his forehead as he pressed it against his forearm. Then he rinsed the chunks of white and yellow down the sink, and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. Then he went and sat back down again, taking up the bacon on his plate, crunching it between his teeth. Sooner or later Dad was going to figure out that there was only one way Sam was going to eat eggs. Ever.

“He wants fried bread, Dad,” said Dean, swallowing down enough eggs for two. “And he likes his eggs scrambled.”

“I can talk, Dean.”

Dean shrugged. He didn’t care, obviously. Today was the day. After morning training, he was going to get to use his new crossbow. Maybe he’d let Sam try it, maybe he wouldn’t. Sam didn’t care either.

“You think you deserve fried bread, after you spit up good food?” This from his Dad, waving a fork that had the white part of the egg on it. “You think you deserve eggs made special just for you?”

Sam hung his head and looked at his hands in his lap. He could eat day-old pizza, brown bananas, knew how to eat around the moldy parts of a slice of bread, could even make a supper out of fried hot dogs and a tin of anchovies. He could eat cheeseburgers every day for a week and would not complain. But he could not eat eggs like that.

“You don’t, you know,” said Dad, and Sam felt his eyes grow hot. It was going to be a horrible summer, especially if Dad got it in his head to break Sam of his finickiness. And no, maybe he didn’t. But he wasn’t going to eat these eggs.

“Dad,” said Dean, standing up with his plate in one hand. “Sam-I-Am is not going to eat those eggs, no matter what.”

“Look at me, Sammy.” This from Dad, and Sam lifted his scowl from his plate. He had only gotten two slices of bacon. His stomach was growling. But he wasn’t going to give in. Lunchtime would come soon enough. Baloney sandwiches or whatever.

“Are you just being stubborn? Trying on this little rebel act about the eggs just for fun?”

Dad’s eyes were dark, his eyebrows coming down just the color of mud. Sam shook his head. He wasn’t being stubborn. It just wasn’t going to happen.

“Dean.”

“Okay.”

Sam looked up. Dean was reaching into the fridge, pulling two eggs out of the carton and then pulling down a bowl to crack them in. As Sam watched his every move, he took a fork and pulled out the cord. Then he beat the eggs, pretending to be using every muscle in his body, grinning at Sam, pretending to concentrate. Scowling at his own majestic efforts. Sam tried not to smile, but it was hard. Then Dad got up and started up the flame under the pan that he’d cooked the bacon in. When it was so hot it sizzled, he dropped slices of bread in, and then stood there, poking at it with a fork to make sure it wouldn’t burn. Dean turned with the bowl in his hand, and after wiping a pan out with a towel, heated up the butter in it. Sam could tell what he was doing by the smell alone, melting butter wafting along the morning breeze. There was a small sighing sound as he eased the eggs in the pan. And then stood there, watching. It was almost funny, the two Winchesters elbow to elbow, cooking breakfast all over again for Sammy.

They presented it to him with a flourish, the eggs golden and soft, folding over and over like waves. A large slice of bread, perfectly fried, and dusted with salt and pepper. Dad put the plate in front of Sammy, while Dean pretended to bow. Then they both sat down, each with a slice of fried bread, dusted with salt, and ate with their fingers. Sam cut into the egg with his fork and brought it to his mouth. Swallowed it down, saying thank you without saying anything at all. Maybe it wouldn’t be a bad summer after all.

*

Only it was. It got worse so fast, Sam thought he imagined it. First there was the run, along the chalk dust road to town and back. Two miles each way as the sun climbed through the trees and the humidity grew so fast it was like a live thing. Sweat had long stuck his shirt and shorts to him by the time they got back to the house. He couldn’t keep up even if he wanted to, but he had to finish. Dean was smiling, still, sweaty all over by the time Sam got to the house, and loving it. Then, after a drink of water, Dad led them into the woods, towards the rocks where the edge dropped off to the river. Sam could feel that it was a little cooler here, but drew himself up short when he saw what Dad had prepared for them.

“Dad,” said Sam, almost choking. “Not the wild woosey.”

“It’s good for balance, son,” said Dad.

Sam kept his mouth shut. He would have rather run to town and back all day than do this stupid thing. There were two ropes tied up to trees and stakes, running parallel to each other. He’d seen Dean and Dad try this one many times, usually slipping halfway because they were laughing. He didn’t see how it improved their balance any, and the one time he’d tried it, at the end of last summer, he’d fallen within the first foot. Dean and Dad had laughed at him so hard, tears had rolled down their faces.

“You and Dean go first. Up, Sammy.”

His whole summer was going to be like this, he knew it. Forced marches in the morning, after a fight over the eggs, and then stupid ropes, and then watching stupid Dean shoot his stupid crossbow. Where he would probably hit the bull’s eye each and every time.

“Don’t you stick your chin out at me, boy. You get up there. This will help your balance, and if you fall, you fall. That’s part of being a hunter.”

Sam opened his mouth, and then snapped it shut, knowing that if he said what he’d thought just then, it would bring more fury down than he had the energy to deal with.

“C’mon, Sammy, it’ll be fun. You and me.” Dean clapped him gently on the back and walked around to the other side of the ropes.

Sam sighed.

Getting up was just as hard as staying up, and Sam slapped at a bug that had landed against his sweaty face before grabbing Dean’s forearms Indian style. They had to climb up at the same time, pulling against each other for balance. But since Dean outweighed Sam by a lot, Sam had to lean further back to balance his brother out. He overbalanced, and landed on the ground on one knee. Dean let go, his hands hard as they slipped off Sam’s arms, and he knew he’d have bruises there within the hour. Dust flew up and more bugs swarmed.

“I’ll help you,” said Dad. And he came forward and lifted Sam up by his waist, holding him on top of the rope, being his ballast while Dean grabbed Sam’s arms again and finally got both feet on the rope. Dad’s hands on him were hard, but they held him steady as Sam scooted sideways, matching his pace to Dean’s. His ribs were starting to feel raw, like they’d been scraped with a brillo pad, and then Dad slowly let go.

“You got it?”

Sam nodded, biting his lip, wanting to wipe the sweat out of his eye, keeping his focus on Dean. Dean was trying to make it okay, giving him a wink and taking it slow, not messing around just to mess with him. But they were about one-third of the way along, doing good, when Sam felt something fly into his eye and he let go of Dean. Who fell over, literally, backwards, rolling down the slope, and not stopping till he hit a bunch of rocks. Hard.

Sam fell to his knees just as hard, but just as he expected Dad to start berating him for being clumsy, Dean made a sound as he tried to get up and Dad took off. Sam was two steps behind him, his knees smarting with grit, thinking that Dean would just get up and they would have to start again, and oh, how he wanted a drink of water.

“Dean?” asked Dad, hunkering down, pushing the undergrowth to the side. “Can you get up?”

“Yeah, I uh-” Dean started and then he stopped and as Sam got close, he could see the reason why. A jagged branch had caught Dean along the calf and opened it up. Through jeans and skin and muscle and everything was bright red. “Uh,” he said, looking up at Dad. “No?” Beneath the streak of mud on his face, he’d gone paper white.

“Shit,” said Dad. “If you hadn’t let go, Sam-”

Dean’s hands were clasped around his calf, but it was going to take more than a bandage to stop the bleeding. Sam guessed stitches, and it wasn’t going to be fun.

“Sam,” said Dad with a snap. “Give me your shirt.”

Sam took it off in a heartbeat, handing it over, wishing it weren’t quite so damp with sweat. Wishing there was something more he could do. But Dad knew what to do. He took Sam’s shirt and wrapped it tight around Dean’s calf, and then scooped Dean up in his arms.

“Sam,” he said now. “Run back to the house and get the first aid out and ready. Run.”

Sam ran, heart beating in his mouth, sweat sticking his bangs to his forehead, but he ran. He heard Dad telling Dean to keep a good hard press against that leg, and then Sam pounded up the stairs and couldn’t hear any more. The first aid kit was on the shelf next to the TV, but Dad wanted everything out and ready. So Sam put everything they might need on the chair, so that way he could move it to wherever Dad put Dean. He put the needle and thread out, the little clamps, the hydrogen peroxide, the cotton bandages, the tape. Everything. His sweat was cooling on his skin as Dad came in, blood from Dean’s leg down his arm, his expression carved from stone.

“The couch,” he said, and Sam swallowed as Dad laid Dean down. Pulled the chair over and stood hard by, waiting for orders. Ran for clean towels, ran for cold water, held Dean’s hand. Watched Dad pulling needle and thread through Dean’s skin. Ten stitches it took, with Dean holding so hard to Sam’s hand that he felt his bones crack.

“Keep that foot up,” said Dad, standing, wiping his hands on the last clean part of the towel. “A few days at least.”

“But Dad, the crossbow-”

But Dad was shaking his head. Slowly. “It’ll be a few days before you can walk on it, let alone stress it. You don’t want stitches to burst and we don’t want to race to the hospital. You keep yourself quiet. The crossbow will wait.”

Dean slammed his head back on the cushions. Nobody looked at Sam. Nobody said anything to him, but he knew it was his fault. He felt cold as his sweat dried, even though it was getting hot in the house.

Then Dad turned to him. “Go get your brother some water while I clean this up. Then get another shirt on, we’re going to go train.”

“But Dad-” started Sam. The thought of training alone with Dad loomed up like a huge gate locking him in with Dad. With the running and the focus and the anger. “I don’t want-”

Dad took him by the shoulder and turned him around. “Not another word. Get Dean some water, and let’s get going.”

Sam went into the kitchen and ran the water till it was cold. His head itched, from bug bites no doubt, and from sweat drying now that he wasn’t in the woods. And then, as he filled a glass with water, he thought about the rifle. He’d been planning to sneak into the cabin at some point or other, when Dean and Dad were occupied with the crossbow. Today, even. He was going to take the rifle out into the woods and bury it where no one would ever find it. But now, Dean would be on the couch all day, and Dad slept there at night. What was he going to do?

Water splashed over his hand, and he realized the glass was full. Overflowing. He turned off the tap and took a huge gulp of the water. It didn’t really help his stomach, but at least he could walk over to Dean and hand the glass to his brother.

“Wait,” said Dad. He eased Dean to a more sitting position and then took the glass from Sam’s hands and gave it to Dean. “You drink that, and take these,” he shook out some painkillers into Dean’s palm, “and I’ll make you some beef broth later.”

Dean looked pale and still as he took the pills and eased them down with the water. There was still a smear of mud on his face, and blood on his elbow and Sam stepped up, reached his hand out to touch.

“Get off me,” said Dean, jerking his head away.

“Get your shirt, Sammy,” said Dad, pulling him back. “Daylight’s burning.”

*

The daylight burned, and Sam’s foul mood along with it. Along with the heat that rose from the ground, up through the soles of Sam’s sneakers, seeming to burn outward from his skin through his shirt. Which was, in about ten minutes, soaked through.

The compass exercises were okay, Sam didn’t mind those. He felt comfortable with the map in his hand, the colored lines and squiggles of the backcountry around Mentone as comfortable as his favorite comic book. In the other hand, Dad’s special compass with the site and the mirror. And the exercises Dad gave him weren’t hard, either. He liked orienting to a map, following a straight line, and finding Dad. That was the best part, to have Dad give him coordinates, simple ones, and then waiting. Waiting five minutes for Dad to walk away, through the woods, and then finding, trying to sneak up on Dad, who would always be leaning against a tree, looking the other way, maybe on purpose, maybe not. And the smile he would get, teeth against the tan, the hand ruffling his hair. The comment that maybe Dad should cut his bangs.

But the sparring? It made Sam want to scream. Yes, Dad pulled his punches, and the bruises wouldn’t hurt after a day or two. Yes, sweat ran into his eyes and the bugs were eating him, but he was used to that. Yes, he knew that Dean, lolling on a couch would much rather be in his place. But if Dad said it one more time, Sam’s head would explode.

“You have to close the distance, Sammy,” said Dad. Again. And then, followed by, as it was always followed by, “And don’t forget to fight to your strengths.”

His head did not explode, but it felt like it wanted to. And his arms hurt from holding them up in the protection position, elbows to chest, curled fists high.

Sam was shorter and lighter, but he couldn’t move that fast, and any time he tried a kick, any kick, Dad could see it coming a mile off. Of course he could, he was ten times taller, and had Dad eyes in the back of his head. And then Dad would go on the attack, and Sam always felt at a loss when he saw the kick coming, because he didn’t know what any of them were called. And each of them had a counter kick. Dean knew. If Dean were here, he might shout it out to Sam and coax him along. As it was, the only thing he knew was when Dad switched from a closed stance to an open one. That Sam could remember. Didn’t help any, as swept his foot out and sent Sam tumbling to the ground.

“Come on, get up, son,” said Dad, reaching out his hand.

Sam rolled himself up to a sitting position, forearms on his knees, tasting dust in his mouth, feeling the sweat pooling near his collarbone. He knocked Dad’s hand away and sat there glowering at his feet.

“This sucks,” he said, muttering.

“It only sucks because you’re not good at it yet,” said Dad, reaching down to pull him to a standing position. Sam felt like a boneless rag doll when he did this. And he did it a lot. “You keep practicing, and you will be.”

“But I don’t want to be,” said Sam, looking up, thinking that this was as good a time as any. “I don’t want to be a hunter, I want to play soccer.”

For a moment there was only silence, so still Sam could hear his heart beating, and Dad’s long indrawn breath while those eyes went dark, and narrow, and hard. Sam swallowed, but he stuck to his ground. Felt his chin jut out, and knew Dad wasn’t going to like that, even before Dad grabbed him by the neck, and pushed him towards the house, making Sam stumble on his own feet.

“We’re done here.”

If Sam had succeeded in ending the sparring match, if that was his dream come true, it wasn’t enough. For in the end, though they had stopped well in the middle of the afternoon with plenty of daylight left for more training, he had done the worse possible thing. He had failed. Failed to hide his distaste for sparring, training, and worst of all, hunting. That was the one thing he was never supposed to say. Dean had told him so. The last time Sam had said it, and the time before that. And the time before that. It was never ending.

Once in the house, Dad rinsed off in the sink, using his hands to splash water over himself, leaving his shirt stuck to his skin. Then, as Sam did the same, he began making the late lunch as Sam took his shoes and sweaty socks off and slumped in his usual chair at the table. From across the room, he could see Dean lying on the couch with his eyes closed.

“Is he asleep?” he asked Dad.

“Wake him up, he needs to eat.”

Sam stood up. Waking up Dean was not the worst task in the world, not normally, since Dean woke up pretty easily. But that was because he had something to look forward to each day. He wasn’t the one who hated every minute of it. Especially a summer like this one.

Sam felt the smack to the back of his head, and tripped forward, catching himself from falling by hurrying.

“Get a move on, Sam, I’m not the maid here.”

With hot eyes, Sam hurried over to the couch, knowing that there was no right way to do this, because if Dean woke up easily normally, he didn’t when he was hurt. Bad. Like he was now. And it was, partly. Mostly. Sam’s fault.

“Dean,” he said, looking down at his brother, at the rise and fall of his chest, the sweat dappled on his forehead, lashes dark against his cheeks. “Dean, wake up.” He pushed Dean’s shoulder with the ends of his fingers. Left a smudge of dust and sweat against the mostly white t-shirt.

“I’m up,” said Dean, barely above a groan. “Not hungry.”

“You’ll eat,” said Dad. He pushed past Sam with a large mug and a packet of crackers. “Eat that. Take it slow.” He handed the mug to Dean and put the crackers on the side of his leg. “If you don’t hurl, I’ll make you a sandwich, and then some more pain pills.”

Dean curled his lip at what was most assuredly beef broth, but he drank it. Popped a cracker in his mouth and let it soak and then swallowed the whole mouthful down. He looked up at Sam with a glower, and Sam turned away. If he started apologizing, started talking, well, there was no telling where that would lead. It was too late to confess about the rifle, altogether too late.

“And you Sam,” said Dad, going back over to the sink. “You want spaghettios in a can, I’m thinking?”

Sam nodded, getting two cans off the shelf, and handed the can opener to Dad. It wasn’t that he couldn’t open his own can, it was just that they had this little tradition, for some reason, that if Dad was in the house, he opened the cans. It was a Dad thing. If he wasn’t there, Dean opened them. Sam didn’t think he’d ever opened a can in his life. He supposed he would at some point. But for now, he just watched. And Dad did it with flair anyway, setting the can down, and crooking in the blade of the opener into the metal in one, tidy motion. He never had to reset the opener, like Dean sometimes did. And his cuts were always of a piece. Smooth, all the way around. Sam got the spoons and glasses for milk, and poured them each some. He had to put the milk back in the fridge right away or it would spoil in the heat. They’d learned that on the first day. Then he sat down, and Dad sat down at the opposite end of the table, plunking a can of cold spaghettios in front of each of them. They tucked in in silence, and Sam sighed as the food slid easily down his throat. Some foods were just better than others, they just were.

*

Two more mornings of runs with Dad before the day got hot, then chopping wood after that, and then lunch with Dean, who fumed under his breath, demanded to be let up. And then afternoons, shooting practice. And then after, handling guns, taking them apart, cleaning them, putting them together, on a table outside in the shade. Which didn’t help any, the humidity had risen so high that you could almost see the water vapor passing before your eyes. And every move Sam made bathed him in salty sweat. He wiped his forehead with the back of his forearm for the hundredth time, only to have Dad knock him on the back of the head. Again.

“You get salt in the gun, Sam, and it’ll jam on you. I’ve told you that, so quit it.”

“Yes, Dad.”

It was like a nightmare. Blisters didn’t matter, the ache in the back of his thighs and arms didn’t matter. The heat, to hell with that, Dad kept him running. Pushing the guns, telling him to pay attention. In the back of his mind, Sam knew what part of it was. Dad was used to training Dean alone, so now, he only had one boy in front of him, and could devote all of his attention there. Sam wanted to say it, I’m not Dean, Dad, but he didn’t dare. Just bit his bottom lip, wiped his hands on the back of his thin shorts and tried again.

“No,” said Dad with a snap, “you unbolt it first, now do it again. Like I said.”

The gun was slippery in Sam’s hands, like the rifle had been. His stomach took a lurch, and he curled his fingers more carefully around the butt.

“Better,” said Dad. “You can’t let your mind wander, not when handling a gun. Loaded or not.”

The final reprieve came at sunset, the heat punching a hole through Sam’s head as he and Dad climbed the stairs. Sam wanted a drink of water and then a shower, was never so glad to be done with the day.

“You’ll be up tomorrow,” said Dad to Dean as he opened the door. Sam scooted under his outstretched arm.

“Awesome,” said Dean. “This couch is giving me a pain in the ass.”

“Watch your mouth, Dean,” said Dad, walking into the kitchen.

“No, I mean it,” Dean’s voice was level, which meant he wasn’t kidding.

Sam turned around slowly to look at Dean, who was trying to lever himself up to a sitting position.

“Really?” asked Dad. “Well, you’ll be up tomorrow, but in the meantime-” he walked over to Dean, and motioned for him to get up, just for a minute. “This old couch,” he said, pulling off the cushions. “Nothing but cloth and wood frame at this point.”

He knelt down and reached around the frame of the couch. Sam could see the places where the sweat had stuck the cloth to Dad’s back, see the grime on the back of Dad’s neck, and then everything went silent. With two hands he pulled out the rifle, now in two pieces, and stood up, looking at what he had in his hands.

“I didn’t do it,” said Sam, from where he stood in the middle of the room. He felt white all over. And suddenly cold.

Dean looked over at him, balancing mostly on one leg, his hand touching the curve of the arm of the couch for balance. “I did it,” said Dean, now looking at Dad. He shook his head for emphasis. “I’m sorry, I-”

Dad stopped him with a look and then turned his head in Sam’s direction.

“Sam, come here.”

Sam made himself walk, though he now could not feel his feet. The gun had been broken for almost a week now. No one had missed it, and he’d forgotten to bury it. Standing next to Dean, he made himself look up. Or tried to. He made it about as far as Dad’s chin.

“Both of you are lying,” said Dad.

“Dad-” said Dean. Starting.

“Don’t cover for your brother, Dean,” said Dad. “Not to me. Now get off that foot.”

Out of the corner of his eyes, Sam watched Dean put the cushions back on the couch and sit down, propping his foot up. Catching Sam’s glance, Dean frowned, like he was asking what happened. Sam wanted to shake his head but didn’t dare.

“You have one opportunity Sam.” Dad motioned with the pieces of rifle in his hands. “One and one only. What happened?”

Sam opened his mouth, but nothing came out. His throat had rocks in it. He swallowed and tried again. Again nothing.

“You will look at me when you talk to me, Sam. Man to man.”

Now Sam had to look up, and lifting his head felt like he was lifting the weight of his whole body. More sweat built on his neck, but he didn’t dare wipe it away. Not with the dark look on Dad’s face, the brows drawn together, mouth in a firm line. Hair sweatstuck to his face. And the grip he had on the rifle pieces looked like it could crush stone.

Part 2