The Things We Carry With Us - Part 7 - Across the Plains and Into the Mountains

Part 7 - Across the Plains and Into the Mountains

In the morning they head out to Nederland for their next gig, but they get a late start.

And Dean lies about them going on as they always have because Dean is not talking to Sam. Except Dean’s idea of not talking is to, really, talk a lot, and say a whole lot of nothing. Shit like gotta fill up for gas soon, and nobody the hell else on the road, why’s that guy driving like a grandma? tumbles from his lips, with almost no breath for Sam to interject. Dean is not and cannot and will not talk about what happened in Canadian, nor what happened in Mammoth Spring, and this, as they drive along a two-lane blacktop means that there is no real communication between them.

Not that Sam can’t interpret the babble as well as he can the silences. Well, almost as well, Dean’s code is written in blood and years and Sam knows what it all means is that Dean is pissed. More than that, he’s confused. Well, Sam’s with him on that one; and whether a blow job equates with a hand job doesn’t matter as much as the fact that Dean seems to have forgotten that Sam is there too. Was there. In the dark, skin to skin, warm, sticky semen drying on his thighs, with the evidence of busted boxers in the morning to prove that what had happened in the night wasn’t his imagination.

That along with the memory of Dean’s blood-hot semen on his tongue, of Dean jerking beneath his hands, and Dean’s plaintive I can’t want that-maybe it means that there’s something more here than what he can readily see.

But Dean is driving like he means to leave that memory behind him, and in no uncertain terms is Sam allowed to direct his attention to what is supposed to become smaller in the Impala’s rearview mirror, metaphorically speaking. Because as far as Sam is concerned, the faster Dean drives, and the further he goes, the bigger it looms.

They leave Canadian and head north on 83 to hook up with 287, going through Boise City. They are cutting across southern Colorado on back roads to make up time, crossing the grasslands of the high plains as the snow starts to come down and the clouds lower in a boiling grey blanket. The land stretches, gritty and yellow, newly torn and yet to settle.

(Highway 83)

Sam remembers something about an Indian massacre that had occurred in the area, and he opens his mouth, not to ask Dean if he knows anything about it, because Dean isn’t interested in stuff like that, but if perhaps they could stop. Sometimes, the way Dean drives, it’s like everything is flyover country, and not worthy of even a small minute’s notice, even if there might be a memorial where Sam can visit and read the placards and maybe feel a little less like he was zipping from one end of the country to the other without knowing anything about the areas he’s passing through.

But Sam knows what Dean will say if he asks. There’s nothing there but arrowheads, Dean will say, and if you want one, I can get one for you, but we’re not stopping.

(Sand Creek Sign)

In spite of the unexpected kindness of the art museum in Canadian, Dean was never big on museums or monuments or anything that way. Sam feels himself scowling, and realizes he’s shut his mouth and it pisses him off that he is already avoiding what he wants, just to head off a stupid argument. Besides, they have other fish to fry. Sam had given Dean a blowjob and Dean isn’t ever going to forgive Sam. Ever. Dean has a tendency to be very particular that way.

“Which way?”

Dean’s voice sounds loud as the Impala slows down for an intersection. Sam looks up from his hands in his lap; the map has fallen at his feet. Sam picks it up, pretending he meant to do that because Dean hates it when the map gets wrinkled or mussed. Which is strange, for all that he can wear bleach stained jeans and blood rumpled shirts, his map and his car are always pristine. Such is the way Dean treats things he values; they give him what he needs, and that is all he asks. In return, tender loving care. Sam thinks that he is not on the precious list at the moment.

He spreads the map across his thighs and looks at it. “Just follow the signs, 287, all the way to Nederland, oh wait-”

Dean interrupts him. “We got a late start. Will we make it?”

Sam peers out of the front window, at the snow blowing like lace through the broken prairie grass on either side of the road. “Five hours?” he says. “Maybe six. The trick’ll be not the darkness but the snow.”

(Blowing Snow)

He doesn’t say it, but the Impala’s tires are fine for highway driving, but are not really suited for drifts and ice. Winter is the time for them to lie up and heal whatever wounds they’ve incurred, and fix the car, and do all that stuff. It’s in the rhythm of their lives; even in medieval times, winter was a time off from war. But to tell Dean this, to mention any of it, let alone imply that his tires might not be capable, no thanks, he’d rather not.

“Snow?” asks Dean. He slows down a bit to lean forward on the steering wheel, looking out at the white flecks whipping across the road as if they mean to be in Kansas before they melted.

“We catch I-70,” says Sam, tracing the map with his finger, “and then the 36, and then Canyon Street in Boulder. That takes us into the mountains. Right into them. It’s almost three thousand feet gain in elevation, which means-”

“Okay, can it, geek,” says Dean. He leans back. “I’ll get us there.”

To prove this, Dean steps on the gas, and soon they are overtaking the grandma driver, and hurtling along the two lane blacktop, under the boiling clouds and away from memory and regret and all those things that Dean acts like he doesn’t want to carry with him. Even though Sam could tell him that while they aren’t physical, there’s no escaping them. His years at Stanford taught them that.

There’s nothing for it but to stare out the window, and watch the clouds come down and swallow the horizon. Sam feels his throat grow dry, and his lips and eyes start to crackle. He wonders if it’s his imagination that the parched air of the high plains is sucking all the moisture out of him, if his knowing that they’re climbing in elevation is making him think of dried mummies and bleached cow hides. But that would take sun; there is no sun, there is only cold and wind and the bluster of dried tumbleweeds taking suicide paths in front of the Impala.

“Goddamn tumbleweeds,” mutters Dean at one point. “Get stuck in my freaking undercarriage, and I’ll fucking end you-”

Dean’s voice fades off as he mutters to himself and Sam lets his eyes close and thinks of pillows.

*

They gas up in Limon and have a quick and tasteless lunch at café the Flying J. It’s like any day at that point: Sam does the windows while Dean pumps up, and after they pay, Sam follows Dean to a table.

(The Flying J Cafe)

He hasn’t brought the notes for the gig with him, though he thought about it. He likes being the one to take care of the notes and update Dad’s journal. It’s not beneath Dean to do research or recordkeeping, no matter what Dad might have felt about it, or why he always gave that job to Sam. Dean can figure things out all on his own without ever writing it down, but both of them know Sam likes that shit, so Dean lets him.

Only let isn’t the right word, Sam knows, because it implies that Dean is in charge, which he most certainly is not. Sometimes, Sam thinks it’s a strange kind of love from Dean, in giving baby brother everything he wants. But it’s because Dean knows him, and knows how much pleasure this kind of thing gives him. Looking up shit, plotting a chart, using a table to graph the variables, everything. And while Dean might make fun of Sam, before, during, and after, he always listens. He gives Sam that and always has. The price of that kind of love, of course, is that Sam is, in turn, to give Dean the gift of sometimes not talking about things. Some times, the price of love is steep.

“I am so tired of chili melts,” Dean says. The bench seats on either side of the booth squeak and groan as they sit down.

Sam nods and does not say that of course, Dean could get tuna salad once in a while, or a stir fry or something with vegetables, but the lure of deep fried anything is far too strong from Dean to resist. And, really, anything more sophisticated than the basics is going to probably be pretty much beyond the capacity of a Flying J truck stop.

Sam looks at Dean around the edges of his menu, a shiny, sharp edged brochure about all the exciting and oversized things that are available. He watches Dean’s eyes track the choices, and sees the very second when the descriptions about the different types cheeseburgers are reached. Dean’s pupils dilate, even, though Sam does not point this out. As mad as they are at each other, food is one of Dean’s pleasures, and since Sam has now fucked up sex for him, maybe for the time being or maybe forever, then perhaps he ought to leave Dean this.

“They’ve got a ribeye,” he says, shaking his menu at Dean to get his attention. He is getting very tired of Dean ignoring him on purpose.

“Cheese steak,” says Dean, “or check out this BLT.”

Sam feels a little dejected about Dean’s refusal.

“They’ve got a steak with wine sauce,” Sam says. “Red wine sauce with mushrooms.” The steaks come with salad and vegetables, which Dean needs. Sometimes, Sam feels like the governess that no one listens to. Like on that old show, Dark Shadows, the governess went around amazed at the vampires and werewolves, but no one else seemed to think it was odd. Likewise, Dean. Who needs vegetables when you have deep fried onion rings?

Sam sighs.

Dean orders the BLT, which, all things considering, at least has lettuce and tomato. Maybe Dean has a special gene and can turn fried lard into pure energy, and can turn noodles into broccoli. The world will never know.

Sam orders the steak with wine sauce, which, when it arrives, is really an unkind thing to call the glop that has been ladled over the fatty piece of meat. But he’s hungry, so he carves around the fat and the bone and pretends the wine sauce is very good. Then he pointedly eats the salad while Dean pointedly moans and groans over the side of onion rings he’s ordered. Trust a place like the Flying J to do those right.

Sam doesn’t dare ask, but Dean pushes the plate at him, and waves his hand over them without looking at Sam. There are three large onion rings left and a nice puddle of ketchup. Sam digs in, and yes, the onion rings are moanworthy.

“Thanks,” he says, crunching around a mouthful.

Dean’s eyes catch his. It’s like catching green fire, and Sam draws in a breath. Then Dean’s eyelashes flutter and Dean looks away, as if he’s contemplating an ice cream Sunday, even if in a place like this the ice cream would be ersatz at best. Though Sam imagines that he might remind Dean of this, he doesn’t.

Dean orders the Sunday anyway and, and as the mound of fake ice cream and syrup melts in the dented aluminum bowl, he leaves most of it uneaten. Sam knows why. Dean can eat most anything, but his ice cream needs to be real, the more homemade the better. Sam wonders if Nederland will have someplace like that and he thinks so; a touristy town would have ice cream parlors decked out in old fashioned faux-Victorian décor. He will find one, and he will lead Dean there. Though whether or not that will make Dean forgive him is another question.

“Ready for the road?” Dean asks as he eyes the bill. He flops out a twenty (drawn from Marvin Hinkle’s account), and shifts himself from the booth seat. “Need to pee?” He asks Sam this without looking at him, and Sam feels the cold wind of how things might be if Dean continues being distant and polite.

“Yeah,” he says.

He leaves Dean by the gumball machines and goes to the men’s room to pee and wash up. He doesn’t look at himself in the mirror, and sees only a glimpse of dark hair and the flair of the whites of his eyes, flickering past so fast they might as well as been someone else’s eyes. By the time he gets outside, the Impala is rumbling right by the exit door, sleek and black against the pale grey cement and glittering beneath the rough, yellow overhead lights that flicker on and off in the growing storm.

Sam slides in to the passenger seat and shuts the door, wincing at the groan and creak that seems to have increased in the cold and altitude.

“We gonna make it?” asks Dean. He backs out of the parking lot, avoiding the semi trucks and other hazards with great care.

Sam doesn’t look at the map; he’s long since memorized it.

“Yeah,” he says. “If the snow doesn’t increase, we’ll make it just fine. Two hours, maybe three, tops.”

Dean backs up and slips over the bridge to meet up with I-70 and heads west. As the pale concrete stretches out in front of them, narrowing at a point far beyond Sam’s ability to focus, Dean actually looks at him.

“Okay, gig. Snow ghost? What’s the deal there?”

Sam slips Dad’s journal from underneath the passenger seat, though really, he’s memorized the information about the snow ghost as well as he’s memorized the map. The long silences and endless miles are good for that, though they have left Sam feeling empty, and he knows he needs to do something with his hands. And maybe, in his own way, Dean knows that Sam needs to do something with his mouth (other than deliver a blow job) and this is his best excuse. And, as excuses go, it’s one they can both agree on. At least dithering about the gig will be better than the vast silences that have filled the interior of the Impala all day.

Sam flattens the journal across his thighs, much as he had the map. His fingers trace the ink that Dad laid down years ago, and imagines he feels the oil from Dad’s fingerprints from where they’d written the pattern of his thoughts. It occurs to Sam, all at once, that at the time, Dad hadn’t expected to die, suddenly, like he did. And that, instead, he’d figured on chasing the demon that killed Mom, and in the meanwhile, would have figured out how a snow ghost worked and what to do to kill it, and then, in the end, made marks in his Yellowboy Carbine to mark how many people he had saved.

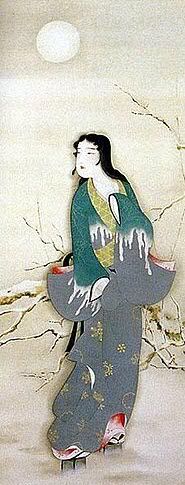

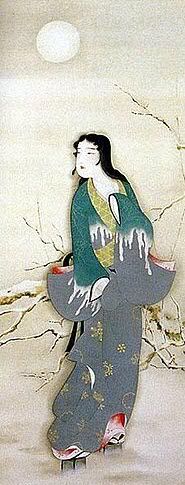

“The snow ghost,” Sam says. He pauses to clear his throat, much as if he is telling a story. Because even if Dean doesn’t like museums and placards and local history, he likes stories. “The snow ghost is an ancient Japanese legend, often referred to as Yuki Onna.” Sam pauses again, and wonders if his Japanese pronunciation is correct, and then realizes that Dean doesn’t care; he’ll take Sam at his word and pronounce the name of the ghost the same way that Sam does, till the day he dies. Even if he is pissed at Sam.

“Some say it wanders looking for its lost child. Others say it wanders, searching for a lover who had gone off to war.”

Sam pauses just as he is about to turn the page. He looks at the Japanese letters, and the sketch that Dad had made; his heart pangs a little. The drawing is good, done with quick, lively strokes. And it’s proportional, too, he can even see the little geta sandals beneath the outlines of a ghostly ink kimono.

(The Yukki Onna)

“So how’d we find this one?”

The question comes as a snap, but Sam knows that Dean is in his own zone, where he’s putting together both what Sam is reciting, and what isn’t even written down. Dad’s journal doesn’t say how he stumbled upon a Japanese snow ghost in the Rocky Mountains, but Sam’s done extra research. And perhaps he’s done this in anticipation of Dean’s asking that very question, because in the knowing of what Dean will ask for, his desire is to give Dean what he wants and needs. But not sex, right? No, never that.

Sam swallows, and pulls out his print outs from the internet. He pretends to read them, keeping his eyes down. “I pulled some FBI files, they were getting reports of people in Nederland going missing in various blizzards.”

“People do,” says Dean, observationally. The tone of his voice is the one he uses when he’s being devil’s advocate for Sam. It’s how they work, and Sam is glad to see it, even if Dean is totally disgusted with him now.

“Yes, but in a town like Nederland-” Sam trails off, wondering how to put this without obliterating the point. “At that elevation, people who live in the mountains know what a blizzard can do.”

“Could be drunks,” says Dean, in the same tone of voice that he used before.

“Yes,” says Sam. He is trying to be patient, even as much as Dean is. It’s how they work; the job has a way of pulling them together as they arrange all the pieces till they make sense. “The FBI got reports about people going missing every blizzard, and they thought the same thing. Drunks, transients, and so forth.”

“What changed their mind? What made up yours?”

“A boy came back,” Sam says. “One boy. He had a story about a woman wearing a white kimono and funny sandals, and how she told him he was so beautiful, she would let him go until he was grown up. And then told him to come back in ten years. The FBI thought he was bonkers, of course.”

“Huh,” says Dean.

Sam looks over. Dean’s mouth is drawn thin. Sam wonders if he’s thinking about beautiful boys, and whether his younger brother could be considered one of those, and Sam shuts his thoughts off so fast, he feels he might have snapped something in his brain.

“Well,” says Dean now. He is comfortable in his seat, with both hands on the wheel. In less than three seconds he’s going to reach for the volume to turn up the music, which, since morning, has been part of the silence. While he listens, he will mull over in his mind what Sam has and hasn’t said. It isn’t a question of not going to check it out, obviously they are already headed there. More, it’s a question of what to do about it when they get there. Which, as Sam knew it would, becomes the next part of what Dean’s thinking. So, not surprisingly, Dean asks, “We’ll have to do research about how to beat the thing, how to kill it. How shall we go in?”

Sam knows what Dean means. FBI agents? Probably the townspeople have already been interviewed and summarily dismissed by the FBI and have had enough.

“Writers?” Sam asks. It’s not Dean’s favorite disguise; he doesn’t read enough about writers to know how they behave. But Dean nods and Sam nods back. A town like Nederland, tucked away from the hustle and bustle, might open up more to a creative type than a suit from the city. “Writing a ghost story.”

It might not come down to that level of detail, but it’s always best to be prepared.

Dean nods and turns up the music, and Sam closes the journal and tucks it back under the passenger seat. The map, he carefully shuts and tucks in the side pocket. Until they reach their destination (the Sundance Lodge), his job is straightforward: get them there without too many wrong turns. Sam prides himself on no wrong turns, and the way the map looks, he will be successful this time around too. Other than that, his job is obvious: don’t bring it up.

*

They hit Denver early enough to mostly beat the rush hour on the freeway, but by the time they’re going through the thick traffic in Boulder, the snow has increased, coming down in thick, bullet-sized flakes that smack on the windshield and layer along the edges of the glass, packing into an ever-thickening layer of ice that simply doesn’t melt. The snow is so dense that even at the start of the canyon heading up to Nederland, Dean is white knuckling it, and Sam is glaring out the window as if by the power of his vision he could get them a bit of blue sky to drive by. But the sky stubbornly remains a massive press of white and grey, and the road is slick with ice the whole way.

As they go higher in altitude, the sky comes lower and lower, boxing them in the high walls of the canyon, till finally they are a contained black dot, the Impala the only non-white or grey thing to be seen. There are no other cars.

(Canyon in a Blizzard)

After an hour of crazy, hairpin turns, and the ice covered rocks rising on either side of the road that is consistently on an increasing grade, everything flattens out. The walls of the canyon move back and there is a low flash of white and grey on the left side of the car, and as Sam looks he sees, under the boil of snow, the flat, almost pristine surface of Baker Reservoir, which, if the map is correct, means that they are almost there.

“Keep going,” he says to Dean. He scrubs the back of his hand across his forehead to push away the ache there and remembers why they don’t do mountain gigs very often. He and Dean are flatlanders, but while the road is just as wide here as anywhere else, the rocks looming up on one side and the sudden drop-off on the other gives his whole body some very clear signals. One spinout and they’re dead.

The town is a haze of flickering lights as they approach, and it is later than they wanted it to be. As Sam sees the blinking warning light for the first intersection, another car passes them, going the other way. It is a small Honda, and its headlights are dim; there is no where for it to be heading than back down the canyon to Boulder. Sam thinks the driver is insane. That, or extremely used to the driving conditions of an early September blizzard.

Dean shakes his head. “Idiot.”

Sam looks at the map in his lap. “Take your first left,” he says. He was going to direct them to a motel a little out of town, the Sundance Lodge. But the snow is too thick and Dean has been driving too far in it; his fingers are white and there are lines on the side of his mouth. Sam is not willing to make Dean go further than he has to, even if the Lodge was one of those little mom and pop places Dean adores. “Take a-”

Dean slows down as he suddenly approaches a confusing little round-about. He looks at Sam.

“Go left,” says Sam. “Circle left-there, 119, so left and left, and, now, go straight.”

Dean goes carefully around the circle till Sam’s finger is pointing straight, like a divining rod. They pass a Gasmat, with gas prices at four dollars, but it seems to be the only place in town. The snow is coming down so hard now, the wipers can’t keep up.

Sam thinks about telling Dean to stop so he can clear the windshield with his bare hands, but he knows they are almost there.

“Just over the bridge,” he says, “and then take your first left.”

The Impala fishtails right in the middle of the bridge, and though Dean corrects the spin by turning into it, Sam can hear Dad in his head, bridges are always icier than the road on either side, so slow the fuck down. Sam knows Dean is worried about the paint job, the chrome fenders, but more, he is worried about taking them into the icy river below. Sam refrains from clutching anything; he stays calm so Dean has one less thing to worry about.

The spin straightens out and Sam can see the yellow and blue Best Western sign glowing through the snow. As Dean turns left into the snow-covered parking lot, he can see it too.

“Best Western?” Dean asks. He’s not stopping, not correcting their course, but his voice says that Sam had better explain himself.

“We can’t keep driving, Dean,” Sam says. “Not in this weather.” He wants to continue in this vein, to tell Dean he can see how tired he is, and maybe he could add how tired Sam is, how hungry they are, how dangerous it would be to insist on that mom and pop place further up the road. But he stops. He doesn’t want to grind it in so hard that Dean resists on principle.

(Cars Humped With Snow)

Dean pulls into the first available slot. The parking lot is only half full with cars humped up with snow, so it is likely that they will be able to get a room. As Dean turns off the engine, Sam digs through the box for their credit cards to find one that they don’t use very often. He comes across Dean’s lighter, the one he’s had for years and couldn’t find.

“Here,” he says. “I found it.”

Dean takes it, almost absently, his thumb smoothing the grime from the chrome edges. “Might as well get a nice room,” he says. “We don’t do this very often.”

Which means that it’s Sam’s turn again to go in and pretend to be whoever the card says he is and get them a room close to an exit.

He knows Dean will check out the car, the undercarriage, the wheels, and hover over his baby while he calms down. He won’t want Sam to see, but Sam sees anyway. As Sam walks up to the front door, he turns his head. Dean has one hand on the car, which is already thick with snow, and he is leaning slightly forward. Sam knows he is breathing hard, and trying to relax all the parts of his body that tightened up during the drive. It was supposed to have been three hours from Limon, it had been six, and they’d not even stopped for lunch.

He turns away from Dean and opens the door, putting his best, friendliest smile on.

The girl at the counter is helpful, and arranges a room, two queens, no smoking. She gives him two plastic keys in the little folder, with the room number written discreetly on the inside, so no passing rapist or mugger will be able to know which room they are in. Which, while Sam considers is a nice and dainty concession, completely ignores the fact that said rapist or mugger could easily follow someone to their room, making the discreteness a moot point. But he doesn’t mention any of this to her; hotels get it in their mind that some little touch is a selling point, and he does not have the energy to overthrow marketing ploys.

“Are there places close to eat?” he asks. “Someplace we can walk to?”

“You’re in luck,” she says, brightly. She pushes a little map at him, sealed in plastic. The local eateries in the map are hand-numbered in bright red letters; their names and corresponding numbers are written on the side. Sam takes a moment to look at the map, and thinks about living a life so sedentary that you could take the time to make something like this, and update it as necessary. It is a life more suited to what he left behind at Stanford, but before he can go spinning off in that direction, he stops himself. It won’t help anything, and Dean is starving.

Sam hears the double doors open behind him, and recognizes Dean’s familiar pace, now muffled by the thick carpet.

“Something fast and hot and filling,” he says now, as Dean comes to stand beside him, their shoulders almost touching.

“You are so in luck,” she says. She points at the map. “Right across the street, and I mean right across. Backcountry Pizza.”

“Perfect,” says Dean.

Sam looks. Dean gives her his special just-the-two-of-us smile, which is reserved for women in their early twenties whose mothers have surely warned them about bad boys like Dean. The girl’s eyelashes flutter in response; she probably doesn’t even know she is doing it. Then duty calls, and the girl turns away to answer the phone. Dean doesn’t look disappointed, it is just something he does, as if the reaction from the flirtee is of no consequence. Sam thinks that Dean had been doing this to Sam, that is, until he stopped.

It is a real hotel, and while the car is going to be miles away from where they are sleeping, there is no help for it. They walk without talking to the elevator. In the elevator, Dean hefts the duffle bags in one hand and hands Sam his backpack. Everything is coated with little black dots, from snow melting. Sam shoulders the backpack and as the elevator doors open, he leads the way to the room.

When he opens the door, the room is warm and clean and dry. Everything is new. Dean sighs as he dumps his stuff on the first bed, nearest the door. Sam doesn’t argue with this, but he never does. It won’t change anything, and he doesn’t want to start a fight, even a little one.

Dean stands there for a minute, pressing his palms to his eyes, and Sam looks down to avoid Dean feeling Sam watching him. He notices that Dean’s sneakers are soaked through. They never did get him new boots. Sam’s feet are soaked through too, and he knows that Dad always said that an army needed good footwear.

“Maybe we can get us some new boots,” Sam says. He opens his mouth to explain that Nederland is a jumping off point for all things mountany, so boots would surely be high on the list of things available to buy. But as Dean drops his hands to look at Sam, there are circles under his eyes, and he is beyond exhausted.

“I could bring pizza back,” Sam says, thinking about how cold the pizza would get, even in the short passage of a street width.

“No,” says Dean. “Just let me get some dry socks at least. And take a piss.”

Sam nods and changes his own socks when Dean does, and looks out the window, pushing back the curtains to look at the snow still coming down. He waits for Dean to pee, for the flush of the toilet and the water running as Dean washes his hands. How many times have they done this, in rooms like this? Many, many times. Well, maybe not this far in the mountains, but yes. Many times.

Dean comes out of the bathroom, and Sam leads the way to the elevator, and then leads the way out the front door. The second they step outside, Sam takes a sharp breath of the thin air and tries to pull his jacket closer around him. It’s obvious that their thin jackets are totally inadequate for the weather; even Dean’s sturdy leather jacket is no match for the altitude and plummeting temperatures. The snow is now coming down in large flakes almost as big as the palm of his hand. He tries to look up, but the sky is too dark to see much and the flakes hit him in the eyes.

Dean grabs his arm and Sam blinks, looking at him through the curtain of snow. He looks at the snow dotting Dean’s hair and at the white splotches on the leather on Dean’s shoulders, and wonders if he’ll ever be able to tell his brother how much he loves him.

“Come on, Mr. Wizard,” says Dean.

They hustle across the street, even though there is no traffic. Sam is completely out of breath inside of two minutes at that pace, and thinks about the extra three thousand feet of elevation and wonders how it could affect him so hard. He doesn’t say anything to Dean; he doesn’t want to be teased, but then he sees that Dean is puffing a bit too, so it’s probably affecting him as well. They keep walking across the parking lot where the snow is up to their ankles, though Sam doesn’t think anyone will be plowing soon. How do people get around? Snowshoes?

Dean is first at the door, and he opens it for Sam with a wave. It’s such a Dean thing to do, making fun of everything, maybe Dean’s forgotten he’s mad.

As Sam crosses the threshold, the warmth and the smell of garlic whaps him in the face, along with other spices, and oil, and beer. The people are all dressed in thick jeans and flannel and there are piles of down coats everywhere. There are booths along the left wall and a bar along the right. There is only one booth open and Sam snags it, grabbing the menu to look at as he sits down. Across from him, Dean does the same. They take off their jackets and tuck them on the seats. It is a good feeling to finally sit at last, to not be moving. To be safe and still and warm, with the promise of food on the way. Hot showers later. A bed. Clean sheets. Darkness.

Sam looks at Dean over the edges of his menu, as he has all of his life, to check how Dean is doing. Dean hates it when Sam fusses, but Sam figures he’s got reason to fuss a little bit. And he wants Dean to tell him it will be okay, that they’ll go on as they always have. But maybe Sam doesn’t want to. Would it matter if they didn’t? How would that change them? Would it?

“Supreme,” says Dean.

Sam looks at the menu, distracted. “No peppers,” he reminds Dean.

“Tell them, then. And add extra cheese.”

This means that the ordering is Sam’s job, this time around. He looks at the huge list of beer. He doesn’t know beer from Adam and usually just gets what Dean gets.

“A pitcher?” Sam asks.

Dean puts his menu down “Yeah. You pick. Ask ‘em what’s good local.” Dean never lets Sam pick the beer, and Sam knows now, if he’d not known before, just how tired Dean is. But maybe a local beer might replace staying at a locally run motel. It’s not that Dean is particularly civic minded, more, it has to do with the fact that Dean feels more comfortable staying at the little places that are under the radar,

A waiter comes up. His hair is clean and shiny and longer than a girl’s. Sam watches as Dean gives the guy his special just-the-two-of-us smile, and Sam wonders if it’s the hair, more than the gender.

The guy doesn’t seem to notice. He’s looking at Sam, as if he knows Sam’s on deck to do the ordering. Sam orders the Supreme pizza without peppers, with extra cheese, and a pitcher of beer.

“What’s good for local beer?” he asks.

“Oh, any of them,” the waiter says. “But we only do pitchers of draft. If you want local, it comes by the bottle. Try the Blue Moon.”

“That sounds good. Two Blue Moons.”

As the waiter goes away with their order, Dean is looking at Sam. The warm air has brought a flush to Dean’s cheeks, and his eyes are that dark shade of green they get when he’s tired. Sam thinks he’s going to have a hard time if his mind insists on going there every time they sit down to eat.

Dean, apparently unaware, says, “That’s going to cost a pretty penny, fancy beer like that by the bottle. We could have just gotten the Bud.”

Sam knows Dean doesn’t really mind. He’s tired and is only bitching to keep in practice. After all, the credit card will pick up the tab.

*

The pizza is cheesy and garlicky, and while it is nothing to write home about, at least it is filling. The beer is too fancy for Dean’s taste, after he finishes the bottle of Blue Moon only halfway, he switches to Bud. Sam finishes all the Blue Moon on the table and orders more. Between them, they polish of six beers and all the pizza.

(Blue Moon)

There is grease on Sam’s fingers and he licks it off. Then he realizes that Dean is watching him, eyes flickering in the overhead lights. Sam shrugs and pulls his hand away. How does a person apologize for something like that, and how could he never not lick his fingers again? He can’t. And when is it, exactly, that they are going to go on like they always do?

“I’m full,” says Dean. He wipes his hands on a crumpled napkin as if to show Sam how it’s done. As if to say, you don’t lick your fingers in front of your brother, because the last time you licked something, it was his dick.

Since the waiter is no where to be found, Dean goes up to the bar to pay. Sam pulls on his jacket and waits for Dean at the booth, and then follows Dean out the door.

The thinness of his jacket feels even thinner on the return trip across the street to the motel. The snow is still coming down, as it has for the whole day, just the same thickness and intensity. Except for the lights streaming from the Best Western’s parking lot, everything is very dark. Sam is no pioneer; he can admire anyone who would come up here to start a town back in the days when they only had candles to light their way. Or maybe they had gas lamps, he’s not sure.

Once back in the room, the door locked and secured behind them, Dean starts taking off everything that is wet. Which means everything, shoes, socks, jeans, flannel shirt, t-shirt, everything. Sam does the same. Standing there in boxers and t-shirt is chilly, even though the heat is on. He figures he’ll warm up soon, now that his damp clothes are off. He pulls open the curtain to watch the falling snow flicker in the streetlights, and the vanishing dark beyond. There is a swath of darkness that cuts between the lights of the houses and buildings on the other side, so he thinks they are in a room overlooking a river, much like they did in the room in Mammoth Spring. Sam clenches his stomach; he wishes he’d not thought of that.

“Next time,” says Dean behind him. “We’re going to the coast. None of this snow shit.”

Sam agrees but doesn’t say anything. Instead he turns on the TV, and listens while Dean rustles up something dry to sleep in and then heads into the shower.

Sam looks through his backpack, but can’t find the paperback book on witch hunts in early Salem. He finds the one on Revolutionary war ghosts, and his notes besides, but as he picks up the book, it feels dull in his hand, and he’s already read it twice. So he puts it away, and pulls back the covers to slip under them. Figuring to brush his teeth and wash his face later, he uses the clicker to flip through channels and finds something on Discovery about lighthouses. This is good, lighthouses are always on the coast, so maybe Dean will agree that they can watch it.

When Dean comes out, Sam looks up. Dean has sweats and a long sleeved t-shirt on, as if he wants to be bundled up as possible, in case any snow drifts start coming into their room. He gives the TV a glance and then rolls his eyes. But he doesn’t say anything as he climbs into bed.

Sam feels as if he’s won this round, but maybe he doesn’t want to win it. Maybe he wants Dean to bitch at him about the Discovery channel, and then he could bitch back about the value of learning. And through the argument that would follow, now that they were dry and fed and not on the road anymore, they can get back to the place where they used to be.

“Here,” he says. He tosses the clicker onto Dean’s bed. It lands between Dean’s thighs, and Sam makes himself look away and focus on the TV.

Without a word, Dean starts clicking. He goes up, hits some sports channels and news channels, and then, he comes back down. He ends up on the Discovery channel again, just as lighthouses changes to sharks.

“Sharks are good,” Dean says. He puts the clicker down.

Sam looks at the clock. It is nine o’clock and he feels like he’s been up for days.

“I’m going to-” He turns away and slips down in the bed, completely forgetting about teeth and face. His head feels like it is filled with stones, and he pulls up the covers and lets his neck relax.

The TV rumbles on without him. He can hear Dean slowly breathing. Within ten minutes, the TV is shut off and the lights go off too. Dean rustles under the bedcovers, and when the silence settles, Sam can hear snow hitting the window.

“You want me to shut them?” he asks.

“No,” says Dean. “I’m good.”

Sam thinks that Dean is listening to the snow hit the window, too.

(Snow on the Window)

~

Part 8 - Brothers in the Snow

Master Fic Post

In the morning they head out to Nederland for their next gig, but they get a late start.

And Dean lies about them going on as they always have because Dean is not talking to Sam. Except Dean’s idea of not talking is to, really, talk a lot, and say a whole lot of nothing. Shit like gotta fill up for gas soon, and nobody the hell else on the road, why’s that guy driving like a grandma? tumbles from his lips, with almost no breath for Sam to interject. Dean is not and cannot and will not talk about what happened in Canadian, nor what happened in Mammoth Spring, and this, as they drive along a two-lane blacktop means that there is no real communication between them.

Not that Sam can’t interpret the babble as well as he can the silences. Well, almost as well, Dean’s code is written in blood and years and Sam knows what it all means is that Dean is pissed. More than that, he’s confused. Well, Sam’s with him on that one; and whether a blow job equates with a hand job doesn’t matter as much as the fact that Dean seems to have forgotten that Sam is there too. Was there. In the dark, skin to skin, warm, sticky semen drying on his thighs, with the evidence of busted boxers in the morning to prove that what had happened in the night wasn’t his imagination.

That along with the memory of Dean’s blood-hot semen on his tongue, of Dean jerking beneath his hands, and Dean’s plaintive I can’t want that-maybe it means that there’s something more here than what he can readily see.

But Dean is driving like he means to leave that memory behind him, and in no uncertain terms is Sam allowed to direct his attention to what is supposed to become smaller in the Impala’s rearview mirror, metaphorically speaking. Because as far as Sam is concerned, the faster Dean drives, and the further he goes, the bigger it looms.

They leave Canadian and head north on 83 to hook up with 287, going through Boise City. They are cutting across southern Colorado on back roads to make up time, crossing the grasslands of the high plains as the snow starts to come down and the clouds lower in a boiling grey blanket. The land stretches, gritty and yellow, newly torn and yet to settle.

(Highway 83)

Sam remembers something about an Indian massacre that had occurred in the area, and he opens his mouth, not to ask Dean if he knows anything about it, because Dean isn’t interested in stuff like that, but if perhaps they could stop. Sometimes, the way Dean drives, it’s like everything is flyover country, and not worthy of even a small minute’s notice, even if there might be a memorial where Sam can visit and read the placards and maybe feel a little less like he was zipping from one end of the country to the other without knowing anything about the areas he’s passing through.

But Sam knows what Dean will say if he asks. There’s nothing there but arrowheads, Dean will say, and if you want one, I can get one for you, but we’re not stopping.

(Sand Creek Sign)

In spite of the unexpected kindness of the art museum in Canadian, Dean was never big on museums or monuments or anything that way. Sam feels himself scowling, and realizes he’s shut his mouth and it pisses him off that he is already avoiding what he wants, just to head off a stupid argument. Besides, they have other fish to fry. Sam had given Dean a blowjob and Dean isn’t ever going to forgive Sam. Ever. Dean has a tendency to be very particular that way.

“Which way?”

Dean’s voice sounds loud as the Impala slows down for an intersection. Sam looks up from his hands in his lap; the map has fallen at his feet. Sam picks it up, pretending he meant to do that because Dean hates it when the map gets wrinkled or mussed. Which is strange, for all that he can wear bleach stained jeans and blood rumpled shirts, his map and his car are always pristine. Such is the way Dean treats things he values; they give him what he needs, and that is all he asks. In return, tender loving care. Sam thinks that he is not on the precious list at the moment.

He spreads the map across his thighs and looks at it. “Just follow the signs, 287, all the way to Nederland, oh wait-”

Dean interrupts him. “We got a late start. Will we make it?”

Sam peers out of the front window, at the snow blowing like lace through the broken prairie grass on either side of the road. “Five hours?” he says. “Maybe six. The trick’ll be not the darkness but the snow.”

(Blowing Snow)

He doesn’t say it, but the Impala’s tires are fine for highway driving, but are not really suited for drifts and ice. Winter is the time for them to lie up and heal whatever wounds they’ve incurred, and fix the car, and do all that stuff. It’s in the rhythm of their lives; even in medieval times, winter was a time off from war. But to tell Dean this, to mention any of it, let alone imply that his tires might not be capable, no thanks, he’d rather not.

“Snow?” asks Dean. He slows down a bit to lean forward on the steering wheel, looking out at the white flecks whipping across the road as if they mean to be in Kansas before they melted.

“We catch I-70,” says Sam, tracing the map with his finger, “and then the 36, and then Canyon Street in Boulder. That takes us into the mountains. Right into them. It’s almost three thousand feet gain in elevation, which means-”

“Okay, can it, geek,” says Dean. He leans back. “I’ll get us there.”

To prove this, Dean steps on the gas, and soon they are overtaking the grandma driver, and hurtling along the two lane blacktop, under the boiling clouds and away from memory and regret and all those things that Dean acts like he doesn’t want to carry with him. Even though Sam could tell him that while they aren’t physical, there’s no escaping them. His years at Stanford taught them that.

There’s nothing for it but to stare out the window, and watch the clouds come down and swallow the horizon. Sam feels his throat grow dry, and his lips and eyes start to crackle. He wonders if it’s his imagination that the parched air of the high plains is sucking all the moisture out of him, if his knowing that they’re climbing in elevation is making him think of dried mummies and bleached cow hides. But that would take sun; there is no sun, there is only cold and wind and the bluster of dried tumbleweeds taking suicide paths in front of the Impala.

“Goddamn tumbleweeds,” mutters Dean at one point. “Get stuck in my freaking undercarriage, and I’ll fucking end you-”

Dean’s voice fades off as he mutters to himself and Sam lets his eyes close and thinks of pillows.

*

They gas up in Limon and have a quick and tasteless lunch at café the Flying J. It’s like any day at that point: Sam does the windows while Dean pumps up, and after they pay, Sam follows Dean to a table.

(The Flying J Cafe)

He hasn’t brought the notes for the gig with him, though he thought about it. He likes being the one to take care of the notes and update Dad’s journal. It’s not beneath Dean to do research or recordkeeping, no matter what Dad might have felt about it, or why he always gave that job to Sam. Dean can figure things out all on his own without ever writing it down, but both of them know Sam likes that shit, so Dean lets him.

Only let isn’t the right word, Sam knows, because it implies that Dean is in charge, which he most certainly is not. Sometimes, Sam thinks it’s a strange kind of love from Dean, in giving baby brother everything he wants. But it’s because Dean knows him, and knows how much pleasure this kind of thing gives him. Looking up shit, plotting a chart, using a table to graph the variables, everything. And while Dean might make fun of Sam, before, during, and after, he always listens. He gives Sam that and always has. The price of that kind of love, of course, is that Sam is, in turn, to give Dean the gift of sometimes not talking about things. Some times, the price of love is steep.

“I am so tired of chili melts,” Dean says. The bench seats on either side of the booth squeak and groan as they sit down.

Sam nods and does not say that of course, Dean could get tuna salad once in a while, or a stir fry or something with vegetables, but the lure of deep fried anything is far too strong from Dean to resist. And, really, anything more sophisticated than the basics is going to probably be pretty much beyond the capacity of a Flying J truck stop.

Sam looks at Dean around the edges of his menu, a shiny, sharp edged brochure about all the exciting and oversized things that are available. He watches Dean’s eyes track the choices, and sees the very second when the descriptions about the different types cheeseburgers are reached. Dean’s pupils dilate, even, though Sam does not point this out. As mad as they are at each other, food is one of Dean’s pleasures, and since Sam has now fucked up sex for him, maybe for the time being or maybe forever, then perhaps he ought to leave Dean this.

“They’ve got a ribeye,” he says, shaking his menu at Dean to get his attention. He is getting very tired of Dean ignoring him on purpose.

“Cheese steak,” says Dean, “or check out this BLT.”

Sam feels a little dejected about Dean’s refusal.

“They’ve got a steak with wine sauce,” Sam says. “Red wine sauce with mushrooms.” The steaks come with salad and vegetables, which Dean needs. Sometimes, Sam feels like the governess that no one listens to. Like on that old show, Dark Shadows, the governess went around amazed at the vampires and werewolves, but no one else seemed to think it was odd. Likewise, Dean. Who needs vegetables when you have deep fried onion rings?

Sam sighs.

Dean orders the BLT, which, all things considering, at least has lettuce and tomato. Maybe Dean has a special gene and can turn fried lard into pure energy, and can turn noodles into broccoli. The world will never know.

Sam orders the steak with wine sauce, which, when it arrives, is really an unkind thing to call the glop that has been ladled over the fatty piece of meat. But he’s hungry, so he carves around the fat and the bone and pretends the wine sauce is very good. Then he pointedly eats the salad while Dean pointedly moans and groans over the side of onion rings he’s ordered. Trust a place like the Flying J to do those right.

Sam doesn’t dare ask, but Dean pushes the plate at him, and waves his hand over them without looking at Sam. There are three large onion rings left and a nice puddle of ketchup. Sam digs in, and yes, the onion rings are moanworthy.

“Thanks,” he says, crunching around a mouthful.

Dean’s eyes catch his. It’s like catching green fire, and Sam draws in a breath. Then Dean’s eyelashes flutter and Dean looks away, as if he’s contemplating an ice cream Sunday, even if in a place like this the ice cream would be ersatz at best. Though Sam imagines that he might remind Dean of this, he doesn’t.

Dean orders the Sunday anyway and, and as the mound of fake ice cream and syrup melts in the dented aluminum bowl, he leaves most of it uneaten. Sam knows why. Dean can eat most anything, but his ice cream needs to be real, the more homemade the better. Sam wonders if Nederland will have someplace like that and he thinks so; a touristy town would have ice cream parlors decked out in old fashioned faux-Victorian décor. He will find one, and he will lead Dean there. Though whether or not that will make Dean forgive him is another question.

“Ready for the road?” Dean asks as he eyes the bill. He flops out a twenty (drawn from Marvin Hinkle’s account), and shifts himself from the booth seat. “Need to pee?” He asks Sam this without looking at him, and Sam feels the cold wind of how things might be if Dean continues being distant and polite.

“Yeah,” he says.

He leaves Dean by the gumball machines and goes to the men’s room to pee and wash up. He doesn’t look at himself in the mirror, and sees only a glimpse of dark hair and the flair of the whites of his eyes, flickering past so fast they might as well as been someone else’s eyes. By the time he gets outside, the Impala is rumbling right by the exit door, sleek and black against the pale grey cement and glittering beneath the rough, yellow overhead lights that flicker on and off in the growing storm.

Sam slides in to the passenger seat and shuts the door, wincing at the groan and creak that seems to have increased in the cold and altitude.

“We gonna make it?” asks Dean. He backs out of the parking lot, avoiding the semi trucks and other hazards with great care.

Sam doesn’t look at the map; he’s long since memorized it.

“Yeah,” he says. “If the snow doesn’t increase, we’ll make it just fine. Two hours, maybe three, tops.”

Dean backs up and slips over the bridge to meet up with I-70 and heads west. As the pale concrete stretches out in front of them, narrowing at a point far beyond Sam’s ability to focus, Dean actually looks at him.

“Okay, gig. Snow ghost? What’s the deal there?”

Sam slips Dad’s journal from underneath the passenger seat, though really, he’s memorized the information about the snow ghost as well as he’s memorized the map. The long silences and endless miles are good for that, though they have left Sam feeling empty, and he knows he needs to do something with his hands. And maybe, in his own way, Dean knows that Sam needs to do something with his mouth (other than deliver a blow job) and this is his best excuse. And, as excuses go, it’s one they can both agree on. At least dithering about the gig will be better than the vast silences that have filled the interior of the Impala all day.

Sam flattens the journal across his thighs, much as he had the map. His fingers trace the ink that Dad laid down years ago, and imagines he feels the oil from Dad’s fingerprints from where they’d written the pattern of his thoughts. It occurs to Sam, all at once, that at the time, Dad hadn’t expected to die, suddenly, like he did. And that, instead, he’d figured on chasing the demon that killed Mom, and in the meanwhile, would have figured out how a snow ghost worked and what to do to kill it, and then, in the end, made marks in his Yellowboy Carbine to mark how many people he had saved.

“The snow ghost,” Sam says. He pauses to clear his throat, much as if he is telling a story. Because even if Dean doesn’t like museums and placards and local history, he likes stories. “The snow ghost is an ancient Japanese legend, often referred to as Yuki Onna.” Sam pauses again, and wonders if his Japanese pronunciation is correct, and then realizes that Dean doesn’t care; he’ll take Sam at his word and pronounce the name of the ghost the same way that Sam does, till the day he dies. Even if he is pissed at Sam.

“Some say it wanders looking for its lost child. Others say it wanders, searching for a lover who had gone off to war.”

Sam pauses just as he is about to turn the page. He looks at the Japanese letters, and the sketch that Dad had made; his heart pangs a little. The drawing is good, done with quick, lively strokes. And it’s proportional, too, he can even see the little geta sandals beneath the outlines of a ghostly ink kimono.

(The Yukki Onna)

“So how’d we find this one?”

The question comes as a snap, but Sam knows that Dean is in his own zone, where he’s putting together both what Sam is reciting, and what isn’t even written down. Dad’s journal doesn’t say how he stumbled upon a Japanese snow ghost in the Rocky Mountains, but Sam’s done extra research. And perhaps he’s done this in anticipation of Dean’s asking that very question, because in the knowing of what Dean will ask for, his desire is to give Dean what he wants and needs. But not sex, right? No, never that.

Sam swallows, and pulls out his print outs from the internet. He pretends to read them, keeping his eyes down. “I pulled some FBI files, they were getting reports of people in Nederland going missing in various blizzards.”

“People do,” says Dean, observationally. The tone of his voice is the one he uses when he’s being devil’s advocate for Sam. It’s how they work, and Sam is glad to see it, even if Dean is totally disgusted with him now.

“Yes, but in a town like Nederland-” Sam trails off, wondering how to put this without obliterating the point. “At that elevation, people who live in the mountains know what a blizzard can do.”

“Could be drunks,” says Dean, in the same tone of voice that he used before.

“Yes,” says Sam. He is trying to be patient, even as much as Dean is. It’s how they work; the job has a way of pulling them together as they arrange all the pieces till they make sense. “The FBI got reports about people going missing every blizzard, and they thought the same thing. Drunks, transients, and so forth.”

“What changed their mind? What made up yours?”

“A boy came back,” Sam says. “One boy. He had a story about a woman wearing a white kimono and funny sandals, and how she told him he was so beautiful, she would let him go until he was grown up. And then told him to come back in ten years. The FBI thought he was bonkers, of course.”

“Huh,” says Dean.

Sam looks over. Dean’s mouth is drawn thin. Sam wonders if he’s thinking about beautiful boys, and whether his younger brother could be considered one of those, and Sam shuts his thoughts off so fast, he feels he might have snapped something in his brain.

“Well,” says Dean now. He is comfortable in his seat, with both hands on the wheel. In less than three seconds he’s going to reach for the volume to turn up the music, which, since morning, has been part of the silence. While he listens, he will mull over in his mind what Sam has and hasn’t said. It isn’t a question of not going to check it out, obviously they are already headed there. More, it’s a question of what to do about it when they get there. Which, as Sam knew it would, becomes the next part of what Dean’s thinking. So, not surprisingly, Dean asks, “We’ll have to do research about how to beat the thing, how to kill it. How shall we go in?”

Sam knows what Dean means. FBI agents? Probably the townspeople have already been interviewed and summarily dismissed by the FBI and have had enough.

“Writers?” Sam asks. It’s not Dean’s favorite disguise; he doesn’t read enough about writers to know how they behave. But Dean nods and Sam nods back. A town like Nederland, tucked away from the hustle and bustle, might open up more to a creative type than a suit from the city. “Writing a ghost story.”

It might not come down to that level of detail, but it’s always best to be prepared.

Dean nods and turns up the music, and Sam closes the journal and tucks it back under the passenger seat. The map, he carefully shuts and tucks in the side pocket. Until they reach their destination (the Sundance Lodge), his job is straightforward: get them there without too many wrong turns. Sam prides himself on no wrong turns, and the way the map looks, he will be successful this time around too. Other than that, his job is obvious: don’t bring it up.

*

They hit Denver early enough to mostly beat the rush hour on the freeway, but by the time they’re going through the thick traffic in Boulder, the snow has increased, coming down in thick, bullet-sized flakes that smack on the windshield and layer along the edges of the glass, packing into an ever-thickening layer of ice that simply doesn’t melt. The snow is so dense that even at the start of the canyon heading up to Nederland, Dean is white knuckling it, and Sam is glaring out the window as if by the power of his vision he could get them a bit of blue sky to drive by. But the sky stubbornly remains a massive press of white and grey, and the road is slick with ice the whole way.

As they go higher in altitude, the sky comes lower and lower, boxing them in the high walls of the canyon, till finally they are a contained black dot, the Impala the only non-white or grey thing to be seen. There are no other cars.

(Canyon in a Blizzard)

After an hour of crazy, hairpin turns, and the ice covered rocks rising on either side of the road that is consistently on an increasing grade, everything flattens out. The walls of the canyon move back and there is a low flash of white and grey on the left side of the car, and as Sam looks he sees, under the boil of snow, the flat, almost pristine surface of Baker Reservoir, which, if the map is correct, means that they are almost there.

“Keep going,” he says to Dean. He scrubs the back of his hand across his forehead to push away the ache there and remembers why they don’t do mountain gigs very often. He and Dean are flatlanders, but while the road is just as wide here as anywhere else, the rocks looming up on one side and the sudden drop-off on the other gives his whole body some very clear signals. One spinout and they’re dead.

The town is a haze of flickering lights as they approach, and it is later than they wanted it to be. As Sam sees the blinking warning light for the first intersection, another car passes them, going the other way. It is a small Honda, and its headlights are dim; there is no where for it to be heading than back down the canyon to Boulder. Sam thinks the driver is insane. That, or extremely used to the driving conditions of an early September blizzard.

Dean shakes his head. “Idiot.”

Sam looks at the map in his lap. “Take your first left,” he says. He was going to direct them to a motel a little out of town, the Sundance Lodge. But the snow is too thick and Dean has been driving too far in it; his fingers are white and there are lines on the side of his mouth. Sam is not willing to make Dean go further than he has to, even if the Lodge was one of those little mom and pop places Dean adores. “Take a-”

Dean slows down as he suddenly approaches a confusing little round-about. He looks at Sam.

“Go left,” says Sam. “Circle left-there, 119, so left and left, and, now, go straight.”

Dean goes carefully around the circle till Sam’s finger is pointing straight, like a divining rod. They pass a Gasmat, with gas prices at four dollars, but it seems to be the only place in town. The snow is coming down so hard now, the wipers can’t keep up.

Sam thinks about telling Dean to stop so he can clear the windshield with his bare hands, but he knows they are almost there.

“Just over the bridge,” he says, “and then take your first left.”

The Impala fishtails right in the middle of the bridge, and though Dean corrects the spin by turning into it, Sam can hear Dad in his head, bridges are always icier than the road on either side, so slow the fuck down. Sam knows Dean is worried about the paint job, the chrome fenders, but more, he is worried about taking them into the icy river below. Sam refrains from clutching anything; he stays calm so Dean has one less thing to worry about.

The spin straightens out and Sam can see the yellow and blue Best Western sign glowing through the snow. As Dean turns left into the snow-covered parking lot, he can see it too.

“Best Western?” Dean asks. He’s not stopping, not correcting their course, but his voice says that Sam had better explain himself.

“We can’t keep driving, Dean,” Sam says. “Not in this weather.” He wants to continue in this vein, to tell Dean he can see how tired he is, and maybe he could add how tired Sam is, how hungry they are, how dangerous it would be to insist on that mom and pop place further up the road. But he stops. He doesn’t want to grind it in so hard that Dean resists on principle.

(Cars Humped With Snow)

Dean pulls into the first available slot. The parking lot is only half full with cars humped up with snow, so it is likely that they will be able to get a room. As Dean turns off the engine, Sam digs through the box for their credit cards to find one that they don’t use very often. He comes across Dean’s lighter, the one he’s had for years and couldn’t find.

“Here,” he says. “I found it.”

Dean takes it, almost absently, his thumb smoothing the grime from the chrome edges. “Might as well get a nice room,” he says. “We don’t do this very often.”

Which means that it’s Sam’s turn again to go in and pretend to be whoever the card says he is and get them a room close to an exit.

He knows Dean will check out the car, the undercarriage, the wheels, and hover over his baby while he calms down. He won’t want Sam to see, but Sam sees anyway. As Sam walks up to the front door, he turns his head. Dean has one hand on the car, which is already thick with snow, and he is leaning slightly forward. Sam knows he is breathing hard, and trying to relax all the parts of his body that tightened up during the drive. It was supposed to have been three hours from Limon, it had been six, and they’d not even stopped for lunch.

He turns away from Dean and opens the door, putting his best, friendliest smile on.

The girl at the counter is helpful, and arranges a room, two queens, no smoking. She gives him two plastic keys in the little folder, with the room number written discreetly on the inside, so no passing rapist or mugger will be able to know which room they are in. Which, while Sam considers is a nice and dainty concession, completely ignores the fact that said rapist or mugger could easily follow someone to their room, making the discreteness a moot point. But he doesn’t mention any of this to her; hotels get it in their mind that some little touch is a selling point, and he does not have the energy to overthrow marketing ploys.

“Are there places close to eat?” he asks. “Someplace we can walk to?”

“You’re in luck,” she says, brightly. She pushes a little map at him, sealed in plastic. The local eateries in the map are hand-numbered in bright red letters; their names and corresponding numbers are written on the side. Sam takes a moment to look at the map, and thinks about living a life so sedentary that you could take the time to make something like this, and update it as necessary. It is a life more suited to what he left behind at Stanford, but before he can go spinning off in that direction, he stops himself. It won’t help anything, and Dean is starving.

Sam hears the double doors open behind him, and recognizes Dean’s familiar pace, now muffled by the thick carpet.

“Something fast and hot and filling,” he says now, as Dean comes to stand beside him, their shoulders almost touching.

“You are so in luck,” she says. She points at the map. “Right across the street, and I mean right across. Backcountry Pizza.”

“Perfect,” says Dean.

Sam looks. Dean gives her his special just-the-two-of-us smile, which is reserved for women in their early twenties whose mothers have surely warned them about bad boys like Dean. The girl’s eyelashes flutter in response; she probably doesn’t even know she is doing it. Then duty calls, and the girl turns away to answer the phone. Dean doesn’t look disappointed, it is just something he does, as if the reaction from the flirtee is of no consequence. Sam thinks that Dean had been doing this to Sam, that is, until he stopped.

It is a real hotel, and while the car is going to be miles away from where they are sleeping, there is no help for it. They walk without talking to the elevator. In the elevator, Dean hefts the duffle bags in one hand and hands Sam his backpack. Everything is coated with little black dots, from snow melting. Sam shoulders the backpack and as the elevator doors open, he leads the way to the room.

When he opens the door, the room is warm and clean and dry. Everything is new. Dean sighs as he dumps his stuff on the first bed, nearest the door. Sam doesn’t argue with this, but he never does. It won’t change anything, and he doesn’t want to start a fight, even a little one.

Dean stands there for a minute, pressing his palms to his eyes, and Sam looks down to avoid Dean feeling Sam watching him. He notices that Dean’s sneakers are soaked through. They never did get him new boots. Sam’s feet are soaked through too, and he knows that Dad always said that an army needed good footwear.

“Maybe we can get us some new boots,” Sam says. He opens his mouth to explain that Nederland is a jumping off point for all things mountany, so boots would surely be high on the list of things available to buy. But as Dean drops his hands to look at Sam, there are circles under his eyes, and he is beyond exhausted.

“I could bring pizza back,” Sam says, thinking about how cold the pizza would get, even in the short passage of a street width.

“No,” says Dean. “Just let me get some dry socks at least. And take a piss.”

Sam nods and changes his own socks when Dean does, and looks out the window, pushing back the curtains to look at the snow still coming down. He waits for Dean to pee, for the flush of the toilet and the water running as Dean washes his hands. How many times have they done this, in rooms like this? Many, many times. Well, maybe not this far in the mountains, but yes. Many times.

Dean comes out of the bathroom, and Sam leads the way to the elevator, and then leads the way out the front door. The second they step outside, Sam takes a sharp breath of the thin air and tries to pull his jacket closer around him. It’s obvious that their thin jackets are totally inadequate for the weather; even Dean’s sturdy leather jacket is no match for the altitude and plummeting temperatures. The snow is now coming down in large flakes almost as big as the palm of his hand. He tries to look up, but the sky is too dark to see much and the flakes hit him in the eyes.

Dean grabs his arm and Sam blinks, looking at him through the curtain of snow. He looks at the snow dotting Dean’s hair and at the white splotches on the leather on Dean’s shoulders, and wonders if he’ll ever be able to tell his brother how much he loves him.

“Come on, Mr. Wizard,” says Dean.

They hustle across the street, even though there is no traffic. Sam is completely out of breath inside of two minutes at that pace, and thinks about the extra three thousand feet of elevation and wonders how it could affect him so hard. He doesn’t say anything to Dean; he doesn’t want to be teased, but then he sees that Dean is puffing a bit too, so it’s probably affecting him as well. They keep walking across the parking lot where the snow is up to their ankles, though Sam doesn’t think anyone will be plowing soon. How do people get around? Snowshoes?

Dean is first at the door, and he opens it for Sam with a wave. It’s such a Dean thing to do, making fun of everything, maybe Dean’s forgotten he’s mad.

As Sam crosses the threshold, the warmth and the smell of garlic whaps him in the face, along with other spices, and oil, and beer. The people are all dressed in thick jeans and flannel and there are piles of down coats everywhere. There are booths along the left wall and a bar along the right. There is only one booth open and Sam snags it, grabbing the menu to look at as he sits down. Across from him, Dean does the same. They take off their jackets and tuck them on the seats. It is a good feeling to finally sit at last, to not be moving. To be safe and still and warm, with the promise of food on the way. Hot showers later. A bed. Clean sheets. Darkness.

Sam looks at Dean over the edges of his menu, as he has all of his life, to check how Dean is doing. Dean hates it when Sam fusses, but Sam figures he’s got reason to fuss a little bit. And he wants Dean to tell him it will be okay, that they’ll go on as they always have. But maybe Sam doesn’t want to. Would it matter if they didn’t? How would that change them? Would it?

“Supreme,” says Dean.

Sam looks at the menu, distracted. “No peppers,” he reminds Dean.

“Tell them, then. And add extra cheese.”

This means that the ordering is Sam’s job, this time around. He looks at the huge list of beer. He doesn’t know beer from Adam and usually just gets what Dean gets.

“A pitcher?” Sam asks.

Dean puts his menu down “Yeah. You pick. Ask ‘em what’s good local.” Dean never lets Sam pick the beer, and Sam knows now, if he’d not known before, just how tired Dean is. But maybe a local beer might replace staying at a locally run motel. It’s not that Dean is particularly civic minded, more, it has to do with the fact that Dean feels more comfortable staying at the little places that are under the radar,

A waiter comes up. His hair is clean and shiny and longer than a girl’s. Sam watches as Dean gives the guy his special just-the-two-of-us smile, and Sam wonders if it’s the hair, more than the gender.

The guy doesn’t seem to notice. He’s looking at Sam, as if he knows Sam’s on deck to do the ordering. Sam orders the Supreme pizza without peppers, with extra cheese, and a pitcher of beer.

“What’s good for local beer?” he asks.

“Oh, any of them,” the waiter says. “But we only do pitchers of draft. If you want local, it comes by the bottle. Try the Blue Moon.”

“That sounds good. Two Blue Moons.”

As the waiter goes away with their order, Dean is looking at Sam. The warm air has brought a flush to Dean’s cheeks, and his eyes are that dark shade of green they get when he’s tired. Sam thinks he’s going to have a hard time if his mind insists on going there every time they sit down to eat.

Dean, apparently unaware, says, “That’s going to cost a pretty penny, fancy beer like that by the bottle. We could have just gotten the Bud.”

Sam knows Dean doesn’t really mind. He’s tired and is only bitching to keep in practice. After all, the credit card will pick up the tab.

*

The pizza is cheesy and garlicky, and while it is nothing to write home about, at least it is filling. The beer is too fancy for Dean’s taste, after he finishes the bottle of Blue Moon only halfway, he switches to Bud. Sam finishes all the Blue Moon on the table and orders more. Between them, they polish of six beers and all the pizza.

(Blue Moon)

There is grease on Sam’s fingers and he licks it off. Then he realizes that Dean is watching him, eyes flickering in the overhead lights. Sam shrugs and pulls his hand away. How does a person apologize for something like that, and how could he never not lick his fingers again? He can’t. And when is it, exactly, that they are going to go on like they always do?

“I’m full,” says Dean. He wipes his hands on a crumpled napkin as if to show Sam how it’s done. As if to say, you don’t lick your fingers in front of your brother, because the last time you licked something, it was his dick.

Since the waiter is no where to be found, Dean goes up to the bar to pay. Sam pulls on his jacket and waits for Dean at the booth, and then follows Dean out the door.

The thinness of his jacket feels even thinner on the return trip across the street to the motel. The snow is still coming down, as it has for the whole day, just the same thickness and intensity. Except for the lights streaming from the Best Western’s parking lot, everything is very dark. Sam is no pioneer; he can admire anyone who would come up here to start a town back in the days when they only had candles to light their way. Or maybe they had gas lamps, he’s not sure.

Once back in the room, the door locked and secured behind them, Dean starts taking off everything that is wet. Which means everything, shoes, socks, jeans, flannel shirt, t-shirt, everything. Sam does the same. Standing there in boxers and t-shirt is chilly, even though the heat is on. He figures he’ll warm up soon, now that his damp clothes are off. He pulls open the curtain to watch the falling snow flicker in the streetlights, and the vanishing dark beyond. There is a swath of darkness that cuts between the lights of the houses and buildings on the other side, so he thinks they are in a room overlooking a river, much like they did in the room in Mammoth Spring. Sam clenches his stomach; he wishes he’d not thought of that.

“Next time,” says Dean behind him. “We’re going to the coast. None of this snow shit.”

Sam agrees but doesn’t say anything. Instead he turns on the TV, and listens while Dean rustles up something dry to sleep in and then heads into the shower.

Sam looks through his backpack, but can’t find the paperback book on witch hunts in early Salem. He finds the one on Revolutionary war ghosts, and his notes besides, but as he picks up the book, it feels dull in his hand, and he’s already read it twice. So he puts it away, and pulls back the covers to slip under them. Figuring to brush his teeth and wash his face later, he uses the clicker to flip through channels and finds something on Discovery about lighthouses. This is good, lighthouses are always on the coast, so maybe Dean will agree that they can watch it.

When Dean comes out, Sam looks up. Dean has sweats and a long sleeved t-shirt on, as if he wants to be bundled up as possible, in case any snow drifts start coming into their room. He gives the TV a glance and then rolls his eyes. But he doesn’t say anything as he climbs into bed.

Sam feels as if he’s won this round, but maybe he doesn’t want to win it. Maybe he wants Dean to bitch at him about the Discovery channel, and then he could bitch back about the value of learning. And through the argument that would follow, now that they were dry and fed and not on the road anymore, they can get back to the place where they used to be.

“Here,” he says. He tosses the clicker onto Dean’s bed. It lands between Dean’s thighs, and Sam makes himself look away and focus on the TV.

Without a word, Dean starts clicking. He goes up, hits some sports channels and news channels, and then, he comes back down. He ends up on the Discovery channel again, just as lighthouses changes to sharks.

“Sharks are good,” Dean says. He puts the clicker down.

Sam looks at the clock. It is nine o’clock and he feels like he’s been up for days.

“I’m going to-” He turns away and slips down in the bed, completely forgetting about teeth and face. His head feels like it is filled with stones, and he pulls up the covers and lets his neck relax.

The TV rumbles on without him. He can hear Dean slowly breathing. Within ten minutes, the TV is shut off and the lights go off too. Dean rustles under the bedcovers, and when the silence settles, Sam can hear snow hitting the window.

“You want me to shut them?” he asks.

“No,” says Dean. “I’m good.”

Sam thinks that Dean is listening to the snow hit the window, too.

(Snow on the Window)

~

Part 8 - Brothers in the Snow

Master Fic Post