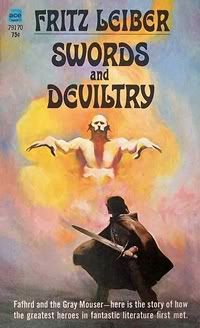

Swords and Deviltry: The First Book of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser by Fritz Leiber

The first collection (by story chronology) of Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories features 3 tales, two from 1970 and one from 1962. Together they detail episodes from the youths of the two heroes, and their fateful first meeting. Although it is ostensibly the start of their story, it may not be the best place to get acquainted with them...

Following an introduction by the author, the first of four items in the book is "Induction", a two page tone-setting piece, briefly describing the world of Nehwon in broad, poetic language. This originally appeared in the collection "Two Sought Adventure", and appears here with a few extra lines at the end to lead into the first full story of the collection:

The Snow Women (1970): This tale of Fafhrd's youth represents his coming of age, and his departure from his people in the North for civilization. Fafhrd's tribe exists in a state of perpetual gender-based "cold war" (a phrase Leiber unashamedly gets out of the way in sentence one). Fafhrd is 18 years old, tall and lean, with "fine red-gold hair". He speaks with a "high tenor voice" due to his training with a singing skald. Though he's old enough to go on pirating raids, and wears the silver bracelets that mark him as a raider, he still lives with his mother, Mor. His father had died some years back, due to ice on a mountaintop.

The women of the tribe are unhappy, due to the annual visit of a trading caravan from the South. The point of their objection is the traveling show which accompanies the caravan every year. The great hall of worship is temporarily given over to performances by "culture dancers": attractive Southern women, who perform dances of many exotic foreign kingdoms, dressed in costume appropriate to the culture presented. Of course, it's a bit warmer down South...

Fafhrd rescues a dancer named Vlana from a mob of snow women (including his own mother) who are pelting the actress with (very icy) snowballs. This puts him in a precarious position. Drawn to the foreign beauty (several years his senior), while semi-betrothed to local girl Mara, Fafhrd attracts the ire of not only his mother and her circle, but of a seasoned Snow Clan warrior named Hringorl, who himself has an eye on Vlana. In the end, the greater danger comes from the subtle magic of the Snow Women, and their chilly disapproval of male wanderings.

The Unholy Grail (1962) introduces us to a young man named Mouse, born and bred in the city, but somehow apprenticed to a hedge wizard named Glavas Rho, who has the misfortune to dwell in the territory of the cruel Duke Janarrl. Mouse is also forming a relationship with the Duke's young daughter Ivrian, herself a constant victim of Janarrl's hateful nature. A fairly intolerable situation escalates, as does the Duke's temper, leading to murder, imprisonment, and torture. It also leads to a somewhat Shakespearean revenge, taken via guilty conscience and the ghosts of the past, assisted, perhaps by subtle magic.

Ill Met In Lankhmar (1970) won both the Hugo and Nebula awards for 1970. We become re-acquainted with our heroes and their respective ladies, now re-established in the mighty metropolis of Lankhmar, an old, powerful, and corrupt city. Having met when both were robbing the same victims, Fafhrd and the re-christened Gray Mouser overcome their initial suspicion to discover that they are kindred spirits. "Fast friends" indeed, as they collect some drinks, and then their lovers, and retreat to Mouser and Ivrian's hidden apartment to have a little drunken house party. In the course of conversation and too much wine, Mouser learns of Vlana's grudge against the Thieves' Guild of Lankhmar (the first such Guild in fantasy fiction, dating back to an early F&GM story). On a run for more wine, Fafhrd and the Mouser talk themselves into making a raid on the Guild-house itself, unaware that a Guildsman has learned the whereabouts of Mouser's home. Tragedy ensues, swiftly followed by bloody vengeance.

What we have here is essentially a collection of prequels. "Ill Met..." in particular has that distinct air of inevitability that one often finds in prequels, as the characters walk a narrow path to where we know they must end up to be able to take part in stories already written. Despite "Ill Met..."'s awards, I find "The Snow Women" to be the meatiest course in this meal. The gender politics, problematic as they are, are front and center, and there's a good dose of satire as well. The subtle environmental magic of the Snow Women is portrayed with an eerie menace which can almost be disbelieved. Almost. "The Unholy Grail" also features subtle magics. The hedge wizardry of Gravas Rho is echoed in the "Headology" of Terry Pratchett's witches; magic is almost a matter of simply knowing more than the other guy. (I think that may, in itself, be an echo of Mark Twain, but I've never read "A Connecticut Yankee...") In the final story, when the villainous Thieves' Guild sorcerer Hristomilo creates a terrifying bit of magic for purposes of silent assassination, it still is represented as a delicate and drawn out process, requiring formulas and equipment. No hasty chanting of spells in Nehwon.

"Grail" is the slightest of the three tales, also the shortest (40 pages, to "Snow Women"'s 120 and "Ill Met..."'s 90). Mouser's actual origins are barely touched on, although Harry Otto Fischer published a short story called "The Childhood and Youth of the Gray Mouser" in Dragon magazine #18 in 1978. (I dug up a pdf of that issue of Dragon, if anyone wants to check out the story.)

Raised by theatrical parents, Leiber's prose can tend towards the flowery. But, possibly due to the relative brevity of the stories (especially compared to the 1000-page monsters of modern fantasy), there's very little excess fat on the bones. There is no history included that is not relevant to the tale at hand, no characters introduced who do not contribute something to the story, no lengthy poems inserted solely for the sake of poetry. Like Raymond Chandler in detective fiction, Leiber shows that style can serve the story without getting in the way.

All in all, this is a fairly atypical assortment of F&GM tales. Only "Ill Met..." gets down to the nitty gritty of sword and sorcery action, and that tale ends up with a rather mournful air not found in most of the canon (not until much, much later.) A better starting point for new readers might be the second book, "Swords Against Death", skipping the first tale (for reasons I'll include in my review of that volume).

if you'd like another opinion, and a more in-depth appreciation of Leiber, I recently found Berin Kinsman's Dire Blog, and his series of Fritz Leiber Studies. I won't be reading those until I actually finish my own series, but it looks like good reading.

Next book: "Assassin's Apprentice" by Robin Hobb

Following an introduction by the author, the first of four items in the book is "Induction", a two page tone-setting piece, briefly describing the world of Nehwon in broad, poetic language. This originally appeared in the collection "Two Sought Adventure", and appears here with a few extra lines at the end to lead into the first full story of the collection:

The Snow Women (1970): This tale of Fafhrd's youth represents his coming of age, and his departure from his people in the North for civilization. Fafhrd's tribe exists in a state of perpetual gender-based "cold war" (a phrase Leiber unashamedly gets out of the way in sentence one). Fafhrd is 18 years old, tall and lean, with "fine red-gold hair". He speaks with a "high tenor voice" due to his training with a singing skald. Though he's old enough to go on pirating raids, and wears the silver bracelets that mark him as a raider, he still lives with his mother, Mor. His father had died some years back, due to ice on a mountaintop.

The women of the tribe are unhappy, due to the annual visit of a trading caravan from the South. The point of their objection is the traveling show which accompanies the caravan every year. The great hall of worship is temporarily given over to performances by "culture dancers": attractive Southern women, who perform dances of many exotic foreign kingdoms, dressed in costume appropriate to the culture presented. Of course, it's a bit warmer down South...

Fafhrd rescues a dancer named Vlana from a mob of snow women (including his own mother) who are pelting the actress with (very icy) snowballs. This puts him in a precarious position. Drawn to the foreign beauty (several years his senior), while semi-betrothed to local girl Mara, Fafhrd attracts the ire of not only his mother and her circle, but of a seasoned Snow Clan warrior named Hringorl, who himself has an eye on Vlana. In the end, the greater danger comes from the subtle magic of the Snow Women, and their chilly disapproval of male wanderings.

The Unholy Grail (1962) introduces us to a young man named Mouse, born and bred in the city, but somehow apprenticed to a hedge wizard named Glavas Rho, who has the misfortune to dwell in the territory of the cruel Duke Janarrl. Mouse is also forming a relationship with the Duke's young daughter Ivrian, herself a constant victim of Janarrl's hateful nature. A fairly intolerable situation escalates, as does the Duke's temper, leading to murder, imprisonment, and torture. It also leads to a somewhat Shakespearean revenge, taken via guilty conscience and the ghosts of the past, assisted, perhaps by subtle magic.

Ill Met In Lankhmar (1970) won both the Hugo and Nebula awards for 1970. We become re-acquainted with our heroes and their respective ladies, now re-established in the mighty metropolis of Lankhmar, an old, powerful, and corrupt city. Having met when both were robbing the same victims, Fafhrd and the re-christened Gray Mouser overcome their initial suspicion to discover that they are kindred spirits. "Fast friends" indeed, as they collect some drinks, and then their lovers, and retreat to Mouser and Ivrian's hidden apartment to have a little drunken house party. In the course of conversation and too much wine, Mouser learns of Vlana's grudge against the Thieves' Guild of Lankhmar (the first such Guild in fantasy fiction, dating back to an early F&GM story). On a run for more wine, Fafhrd and the Mouser talk themselves into making a raid on the Guild-house itself, unaware that a Guildsman has learned the whereabouts of Mouser's home. Tragedy ensues, swiftly followed by bloody vengeance.

What we have here is essentially a collection of prequels. "Ill Met..." in particular has that distinct air of inevitability that one often finds in prequels, as the characters walk a narrow path to where we know they must end up to be able to take part in stories already written. Despite "Ill Met..."'s awards, I find "The Snow Women" to be the meatiest course in this meal. The gender politics, problematic as they are, are front and center, and there's a good dose of satire as well. The subtle environmental magic of the Snow Women is portrayed with an eerie menace which can almost be disbelieved. Almost. "The Unholy Grail" also features subtle magics. The hedge wizardry of Gravas Rho is echoed in the "Headology" of Terry Pratchett's witches; magic is almost a matter of simply knowing more than the other guy. (I think that may, in itself, be an echo of Mark Twain, but I've never read "A Connecticut Yankee...") In the final story, when the villainous Thieves' Guild sorcerer Hristomilo creates a terrifying bit of magic for purposes of silent assassination, it still is represented as a delicate and drawn out process, requiring formulas and equipment. No hasty chanting of spells in Nehwon.

"Grail" is the slightest of the three tales, also the shortest (40 pages, to "Snow Women"'s 120 and "Ill Met..."'s 90). Mouser's actual origins are barely touched on, although Harry Otto Fischer published a short story called "The Childhood and Youth of the Gray Mouser" in Dragon magazine #18 in 1978. (I dug up a pdf of that issue of Dragon, if anyone wants to check out the story.)

Raised by theatrical parents, Leiber's prose can tend towards the flowery. But, possibly due to the relative brevity of the stories (especially compared to the 1000-page monsters of modern fantasy), there's very little excess fat on the bones. There is no history included that is not relevant to the tale at hand, no characters introduced who do not contribute something to the story, no lengthy poems inserted solely for the sake of poetry. Like Raymond Chandler in detective fiction, Leiber shows that style can serve the story without getting in the way.

All in all, this is a fairly atypical assortment of F&GM tales. Only "Ill Met..." gets down to the nitty gritty of sword and sorcery action, and that tale ends up with a rather mournful air not found in most of the canon (not until much, much later.) A better starting point for new readers might be the second book, "Swords Against Death", skipping the first tale (for reasons I'll include in my review of that volume).

if you'd like another opinion, and a more in-depth appreciation of Leiber, I recently found Berin Kinsman's Dire Blog, and his series of Fritz Leiber Studies. I won't be reading those until I actually finish my own series, but it looks like good reading.

Next book: "Assassin's Apprentice" by Robin Hobb