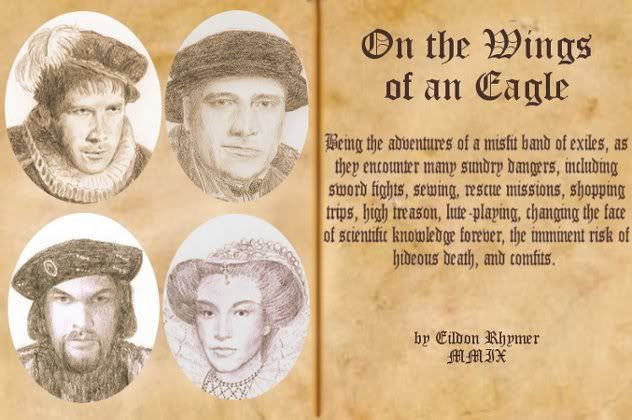

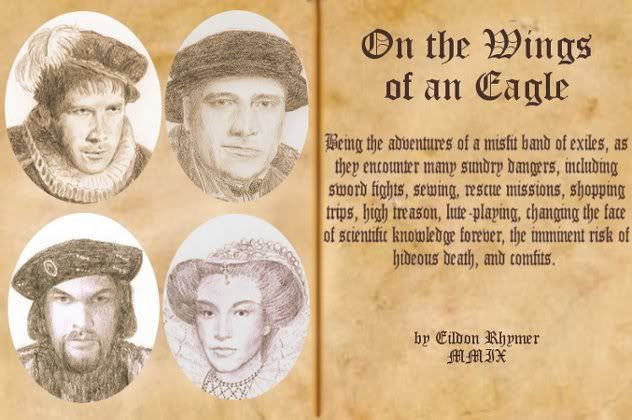

SGA fic: On the Wings of an Eagle - part 1 of 5

Title: On the Wings of an Eagle - part 1 of 5

Author: Eildon Rhymer (rhymer23)

Words: c. 50,000, plus 6 pictures

Rating: PG

Genre: AU (also adventure, some angst, some humour, some h/c, and some illustrations)

Spoilers: None

Summary: It started with a man crashing into a herb garden. Soon a misfit band of four exiles are caught up in a wild ride of sword fights, sewing, rescue missions, shopping trips, high treason, lute-playing, changing the face of scientific knowledge forever, the imminent risk of hideous death, and comfits.

Note: Written for the bonus round of the sga_genficathon, in the genre of AU, and the prompt "Those magnificent men in their flying machines". Something about gen ficathon bonus rounds seems to bring out the illustrated historical AU in me. Last year I did The Pirate's Prisoner, and this year I've gone back nearly 200 years to the year 1555. For a prompt about flying machines. Er, yes, well. I suspect that normal people wouldn't see a prompt about flying machines and immediately think "We'll have Tudors! With planes!" but I blame Leonardo Da Vinci. He famously designed flying machines on paper, but didn't get them to work, but he was merely Leonardo; he wasn't Doctor Rodney McKay.

I've tried to explain the historical background as and when it becomes relevant, but a very quick outline can be seen here

******

Chapter one

In which Rodney has an encounter with a mysterious stranger, served with a side dish of herbs

__

Rodney McKay had almost designed the first genuine perpetual motion machine known in Christendom, when an impertinent rogue crashed out of the sky and landed in his knot garden.

Such occurrences did not happen very often in the Year of Our Lord, fifteen fifty-five, the however-manyth year of the reign of Queen Mary, God preserve her, etcetera etcetera. It caused Rodney's pen to snap, flooding ink across the page. Cursing, he reached for his sand-shaker to soak up the ink, but his trembling hand struck the ink bottle and toppled it over. His beautiful designs were eaten by the encroaching blackness. Sand was no use, not against a catastrophe of such magnitude. The dark cloud of brutality and ignorance always triumphed over enlightenment in the end.

Rodney stood up furiously, his chair scraping on the floor. At that point, of course, he didn't know that an impertinent rogue had crashed out of the etcetera etcetera, just that an ungodly noise had come from the direction of his knot garden. He thought it was probably foxes, or maybe badgers, his old nemeses. Whatever it was, it had interrupted his work, and that meant that it needed to be dealt with.

"Uh, deal with that, Kavanagh," he shouted, but there was no answer, and no sound of scurrying manservant rushing to defend his master's life with his own. Of course not, Rodney thought crossly. Kavanagh was a deep sleeper, and it was… Rodney reached for the heavy watch he wore round his neck, and peered at it in the light of a guttering candle. The hand was somewhere between the XI and the XII. So how dare something make a noise in my garden, Rodney fumed, at a time when all decent people are asleep? Part of his mind recognised the flaw in his outrage. He ignored that part determinedly.

Swept along by a carefully-nurtured wave of fury, Rodney reached down a lantern from the kitchen shelf, and lit it from a candle sconce. There were a lot of bolts on the back door, for reasons that had made sense at the time. Outside was chilly, with a sense of huge and endless vistas, full of unpleasant, nameless things. The flame inside the lantern looked very tiny in the vastness that was the world.

"Uh…" Rodney made an inarticulate sound, his mouth suddenly very dry. Maybe it wasn't quite such an unforgivable thing after all, he thought, to ruin his designs for a perpetual motion machine and to cause enlightenment to be extinguished with a dark cloud of brutality, ignorance and ink. Perhaps it could be forgiven and forgotten, if he went back inside and locked the doors and closed the curtains around his bed and lay there very still with his pillows over his ears. Discretion was the better part of valour, after all, so that would be the valorous thing to do, the brave thing, the…

Something stirred in his knot garden. In the light of the crescent moon, Rodney saw an enormous brutish shape rearing up from his rosemary bushes.

The lantern slipped from his fingers and crashed onto the gravel, the glass shattering. It was… uh, a… a tactical decision - yes, of course it was - because the light would have helped his attacker pinpoint his location.

"Who's there?" Rodney bravely demanded. The scent of rosemary was strong and cloying. "You…" Rodney swallowed. The best remedy for abject terror was always fury; it had enabled Rodney to survive things that had felled lesser man. "You're ruining my knot garden."

"It's not a very good knot garden," a voice replied from the darkness. It definitely wasn't a badger.

"But it's my knot garden," Rodney said, suddenly realising that the reputation of his knot garden was more important even than designs for perpetual motion machines that would make him the toast of Christendom, and perhaps even the more enlightened of the heathens. "And you're not supposed to be in it."

The dark shape lurched forward, and the smell of crushed thyme joined the rosemary. As well as abject terror and fury, Rodney was suddenly ravenous for roast fowl, pleasingly stuffed. He swallowed hard, and forced himself to concentrate on the fact that he was probably going to get bloodily murdered so close to his own back door. When had he last eaten, anyway?

"I apologise," said Rodney's murderer. "It… happened. I'd intended a more conventional approach."

Rodney began to back defiantly away. "How did you get in, anyway? I mean, hello? Outer walls with spiky things on them? Impenetrable locks, designed by yours truly? Security impossible to breach? Though the badgers and foxes get in by digging, but I'm working on that. Rabbits, too."

His murderer moved on to crushing sage. "There's another way, of course. I'm thinking that if I've come to the right place, and you're really Rodney McKay--"

"Doctor Rodney McKay," Rodney corrected him stiffly.

"Then you'd know this," his murderer finished, his deadly path hung around with an aura of chives.

Rodney took a few more steps backwards, but his sense of direction was confused in the dark, and parsley joined the fragrant mix. "So, uh, if you were specifically trying to find me, you…" He tripped over a low hedge, and only just managed to avoid falling backwards onto the gravel. "Have you come to assassinate me?" he managed to ask with furious dignity.

The dark shape was still mired down in chives. "Why would I want to do a thing like that?"

"Oh, many reasons." Rodney straightened his doublet, smoothing it down. "I served the late King Edward, and Protector Somerset was my patron, whose name is, of course, anathema to the present regime. I created wonders for his armies, and all those secrets are now forgotten by everyone but me. Why, just this evening, I was on the verge of creating a perpetual motion machine, and I would have done so if it wasn't for you. Unfortunately, the present Queen has no interest in enlightenment, and banished me, would you believe, to this godforsaken backwater in the country, and commanded me to stop my ungodly work. Ungodly, I ask you! People always fear that which they do not understand."

The dark shape was wrapped in a miasma of chives. "You make a tempting case," it said, "but I think I'll pass for now."

A barn owl flew low overhead; Rodney's sharp squawk was one of defiance, of course, and not terror. "Then if you haven't come to kill me," Rodney snapped, "why are you here? You're… you're a dark cloud of brutality and ignorance. You interrupted my work! Work's all I've got left, and you…" He scraped his hand across his face, exhaling sharply. "You interrupted me," he said, "and I don't know what you want, and I don't know how you got here, and things aren't meant to be like this."

"I'm sorry," said the dark shape quietly. "I came for your help, but I lost control. I left it too late. I'm afraid I broke her up a bit."

He stepped forward and became a tall man dressed in black. A moment later, he fainted, crumpling to his side in the parsley and chives.

******

John drifted awake to find someone shaking him. His heart lurched, and he lashed out, memories of dungeons pressing down on him. His hand struck something solid. "No!" someone squawked, and, "Don't!" but John's other hand found his dagger, and he wrenched it out of its sheath.

"Are you crazy?" squeaked the voice. "You said you weren't going to kill me. Oh. Oh. I see. You think…" The voice tried to turn soothing. The feel of the dagger in John's palm was more soothing still. "I'm not going to hurt you. Nice mysterious stranger. Good mysterious stranger. Just, uh, lie still, and, er, do whatever people are supposed to do when they… I think you've hurt your head. It's all blood-stained. You fainted."

"Yeah." John moistened dry lips. "That explains the regiment of drums pounding in my skull." There was more, too, but he had long-since learnt not to show weakness when it wasn't necessary. He tightened his grip on his dagger. He knew where he was, of course, but the memories circled like carrion crows, still too close for comfort. The dagger helped.

McKay was standing over him, a lantern trailing from one hand. "Ow," McKay said pointedly, when he saw John looking at him. His other hand rubbed his shoulder, thumb massaging the collarbone. "It's quite impolite," he said, "to break into someone's knot garden, faint in their parsley and then attack the person who's trying to prod you back to life again."

John managed to stand up; he had never liked being on the ground when other people were standing. Everything swayed, but it was nothing he couldn't deal with. The memories that had resurfaced upon awakening had quite driven away the temptation to bait this man. "I need your help," he said wearily. "My puddlejumper's broken." Then he glanced over his shoulder, covering the twist of pain with a wry smile. "More than broken now, of course. I need you to fix her. Please." His voice cracked; he hadn't meant it to.

"Puddlejumper?" McKay echoed, frowning.

John gestured weakly in the appropriate direction. He tried not to shift uncomfortably as McKay slowly walked away, taking the light with him. In the protection of the darkness, his hand rose to his brow, feeling blood on the side of his face. Even when he touched it gently, pain flared throughout his skull. His silenced gasp of pain caused an answering stab of pain deep in his ribs. Pressing his forearm across his middle, he watched the lantern bob through the herb garden. Of course he had to let McKay see her. Of course he had to let McKay touch her. It is kind of the point, John.

"It's probably a trap," McKay was muttering. "You've got an accomplice out here in the potager. I'm armed, varlet! I'm a skilled fighter, h-hiding my light under a bushel. I've killed dozens of rogues. I'm--" His voice broke off. The lantern went very still. John counted slowly to twenty, and still McKay didn't move.

"But they destroyed them all," McKay said at last, his voice very different from anything that had gone before. It sounded as if all masks had been stripped away from him, and this, this, was the real McKay. "The Queen had them destroyed. All of them. There were none left."

"I guess she didn't get all of them." John tried to keep his voice light, but it caught on the last word.

"How?" The lantern swung round, and came back, swinging from side to side.

"I escaped." His words were quiet in the vastness of the darkness. He pressed his arm tighter against his body, fingers digging into the flesh of his side. "I grabbed the jumper and got the hell away from there. The Queen's men couldn't stop me." The darkness was thick with memories. He spoke over them with a level voice, and refused to let them come out to play.

"But that was almost two years ago," McKay said. He was close enough now for John to see his face. John turned his own face slightly to the side. "How have you kept this a secret for so long? What have you been doing?"

John shrugged. "I keep my head down."

"But how…?" McKay began. John heard his feet crunching on the gravel, and he clenched his fist tightly at his side, fingers digging into his palm. "Why didn't I know about it? I invented the things. I have a right, you know. They're mine. The first functional flying machine in the whole history of the world outside the realms of silly legends. People talk about the great Signor Da Vinci, but his were just paper plans, deeply flawed. I, I, Rodney McKay, Doctor Rodney McKay, was the first person to make flight possible, and the Queen burned my machines and banished me and said that my creation would be expunged from the annals of history forever more, when it should be sung to the heavens and glorified."

"I remembered," John said quietly. McKay's ranting made the horrors retreat even further. He focused on the pool of lantern light and the sweetness of the crushed herbs. "She's not been working so well lately. I found out where you lived and came--"

"And why do you call it by that ridiculous name?" McKay demanded. "The correct name is Doctor Rodney McKay's Aeronautical Machine, Mark III. And you've broken it. The only surviving proof of my dazzling accomplishment, and you've broken it."

John turned towards the wreckage hidden in the darkness. "I'm sorry," he murmured, and then the darkness took him again.

******

There was nothing for it, of course, but to drag Kavanagh out of bed. "There's a man in my parsley," Rodney told him. "He's fainted. I believe that the usual course of action would be to bring him inside and put him by a nice warm fire." Kavanagh just blinked at him. "So jump to it," Rodney commanded.

They had to do it together in the end. Quite a lot of herbs were irredeemably crushed. "Which reminds me," Rodney gasped, hefting the mysterious stranger's limp legs, "I would like roast fowl tomorrow, with parsley and sage stuffing, and no lemon balm this time, or my wrath will… indeed be… terrible." He dropped a leg. Kavanagh grunted, but managed to keep the man's top half off the ground. Rodney managed to grasp the mysterious stranger's leg again. He had the irritating leg of a courtier who liked to pose for portraits in too-short breeches. He was slim beneath his doublet, too. Ladies would doubtless swoon at his feet. Rodney decided that he disliked him intensely.

"Who is he?" Kavanagh asked, staggering on the gravel. "How did he get here?"

Sometimes if you ignored a question, it obligingly went away. "Concentrate on… getting him… inside," Rodney gasped. Carrying an unconscious man was harder than it looked. The dashing soldier types with their shapely legs had made it look much easier than this, when Rodney had cowered… that is, when Rodney had maintained a tactical vantage point behind the baggage train during Protector Somerset's campaigns against the Scots. Of course, military types were all about show, and doubtless thought that Euclid's Elements was a salve for boils, newly introduced from Italy.

"What's wrong with him?" Kavanagh asked, as they crossed the threshold.

Rodney contemplated stairs, and the effort needed to lift an unconscious man onto a bed. "We'll put him in my study," he said, "on the floor… next to… the… fire." It was probably better for him, anyway. Elevation would… something something… detrimental to his injuries… things like that.

When the mysterious stranger was safely dumped… that is, safely placed on the rug, Rodney straightened a weary back and flapped a weary hand. "Get… what we need."

Kavanagh still looked half asleep, clad in a crumpled robe. "What do we need?"

"Don't you know?" Rodney expressed the appropriate outrage. "I thought you wanted to be called a student of natural philosophy. That's what you told me, anyway."

Kavanagh had come to Rodney as his apprentice, his acolyte, his disciple, his minion; Rodney changed his mind from week to week about which title was the most gratifying. When an unsupervised and unauthorised investigation into the principles of combustion had resulted in the loss of twenty-seven priceless volumes from Rodney's library, Kavanagh had been demoted to manservant until the debt had been paid off. Since the books had been priceless, Rodney calculated that Kavanagh would be serving for the whole of eternity. Fortunately arithmetic had never been Kavanagh's strength, and he accepted his term of durance. Debtors' prisoners were worse.

As Kavanagh rummaged noisily in the kitchen, Rodney went to his shelves and took down a slightly charred volume. Kneeling beside the man, he leafed through the book with a weary hand.

"What you reading?" the mysterious stranger mumbled.

"Oh, now he wakes up!" Rodney cried. "You could have woken up when we carried you in from the garden. I think my back's ruined forever."

The mysterious stranger gave a faint smile. "I thank you for sacrificing your future health for my sake."

"Well…" Rodney cleared his throat. "It wasn't really for your sake. I can't have you dying on me, not if you're the only person anywhere near here who can actually fly one of Doctor Rodney McKay's Aeronautical Machines, Mark III. They used to tell me it took extraordinary skill. Not as much skill as inventing the things, of course. I mean, all you have to do is sit there and pull a few levers."

Firelight flickered on the mysterious stranger's face, filling its hollows with deep shadows. "Fly them yourself, do you?"

"God's blood, no! What do you take me for?" Rodney stopped, smoothed down the open page, straightened his doublet. "I could, of course, but…" He swallowed; tried to think of the correct words to express his tactical decision to contribute to Protector Somerset's flying project at a discreet distance.

"Yeah," the mysterious stranger murmured, smiling again. "I get it. Only a crazy person would jump off a hill, entrusting his life to wood and canvas. You have to find the air currents, like birds do. You get a sense for them. You learn how to manipulate the propellers and flaps to use them best. Crazy." His eyelids began to flutter shut.

"Oh. Oh. You're not getting delirious, are you?" Rodney leafed faster through the book.

The stranger's eyes opened again. "What's the book?" he asked again.

"Vesalius," McKay told him proudly. "De humani corporis fabrica. Not the abridged version, either, but the full seven volume set. Of course," honesty compelled him to add; he was admirably fair-minded when it came to admitting other people's errors, "my idiot manservant caused most of the volumes to be destroyed by fire, and all I've got left is volume six." He turned to the title page. Volume six was apparently about the organs of digestion and reproduction. He closed it casually, with the air of someone who had learnt all he could from it. "Books contain wisdom," he said, because you had to explain things to illiterate people of lesser intellect. "It'll allow me to repair you."

The mysterious stranger managed to turn his head so that almost no light fell on his face at all, despite his closeness to the fire. "Repair my jumper instead," he said. "I'm good."

Rodney pushed the book away, sliding it across the floor. There was little that the master of anatomy could teach him, after all. It was out of date, anyway; Kavanagh had come back from Oxford with reports of a second edition. Kavanagh, bumbling fool that he was, still had contacts. Rodney had lived barely a dozen miles from the university for almost two years, and not one single person had sought him out. This stranger, Rodney realised, was the first guest that the house had seen since his father had died. His father had survived only one month of Rodney's banishment. His last words had not been kind.

"For the last time," Rodney said crossly, "don't call it by that ridiculous name." He stood up and went to shelve the book. His hands were shaking, fumbling with the volumes. Kavanagh was silent now in the kitchen. A faint scent of herbs still clung to Rodney's clothes, and Rodney suddenly remembered his childhood, and his mother's smiling delight in her new-style garden. He tended it whenever memory struck him. Most of the time, though, he considered it stupid.

The stranger was watching Rodney when he turned back, and unlike many people that Rodney had known over the years, he made no attempt to hide it when he realised that he had been discovered. That made Rodney feel… Well, he wasn't quite sure what it made him feel. "What's your name, anyway?" he demanded harshly.

The stranger nodded, giving an imitation of a bow that was surprisingly effective for someone lying on their back with blood on their face. "John Sheppard, at your service."

"That would be Sir John Sheppard, then," Rodney said bitterly. The late king had thrown knighthoods at all his pilots, despite the fact that they were expendable fools. Rodney, by contrast, had received only grudging acceptance, and many of the courtiers had been quite unforgivably rude. Then he frowned, struggling to remember. He'd never bothered to make the acquaintance of the thrill-seeking idiots who'd flown his precious creations. The moment the six machines had been put into active service, Rodney had already been closeted in a series of chambers, working on Doctor Rodney McKay's Aeronautical Machine Mark IV. It involved balloons. "Are you any relation of--?"

"He was my father," Sheppard said, in a tone that even Rodney could recognise brooked no argument.

"Oh." Rodney swallowed; moistened his lips. "Weren't you, uh, arrested?" All the pilots had been arrested; he remembered that now. The Duke of Northumberland had used several of Rodney's flying machines in his attempt to put his daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey, on the throne of England instead of the present Queen. Whether guilty or not, the whole lot of them had been accused of treason. It was the loss of his beautiful machines that had filled the first few months of Rodney's exile with rage and despair, and the withdrawal of patronage that had made the next two years cold and bleak and empty, but people had died - less important than any of that, of course, but, still…

"I got away." Sheppard's face was a closed door. The room felt suddenly colder.

And hadn't his father…? Rodney pressed his lips together. Kavanagh would know; he relished tales of execution and the fall of great lords.

As if summoned by his thoughts, Kavanagh entered the room, a bowl of warm water steaming in his hands and a towel draped over his arm. "There's someone at the gate," he said, his eyes flickering between Sheppard and Rodney.

"Oh." Rodney sank down into the nearest chair, then stood up again, clasping his hands together with consternation. Sheppard was a wanted man; of course he was. He was an escaped prisoner. He was an outlaw. He'd flown an illegal flying machine through the night sky of north Oxfordshire, and had crashed it into Rodney's knot garden, like a giant arrow saying, 'I am here!' Rodney would be dragged away to a prison vile and clapped into chains, and… and tortured, tortured hideously, when it wasn't his fault, "and it's not fair," he said. "You just landed here without a by-your-leave. It's not fair to get me killed because of it."

Sheppard had managed to stand during Rodney's entirely justified bout of mild panic. With the firelight behind him, he looked quite heroic in a way that suddenly seemed more gratifying than irritating. Even his legs no longer seemed vexing. "Let's see who it is, then," Sheppard said. His dagger was in his hand.

Rodney watched him walk to the kitchen door; drifted into the kitchen himself and heard Sheppard begin to walk across the gravel. Sheppard stopped a few paces away. "Shut the door," he said, "and bolt it, just in case."

Rodney was grasping the edge of the door frame, fingers digging into the wood. "And allow you to go off all unobserved and let your accomplices in?" His voice was quiet. He cleared his throat, his hand clammy against his mouth. "You're probably too stupid to recognise a threat, anyway." He went to the back door. The scent of herbs was gone, swallowed up by the cold smell of an unfriendly night.

Sheppard had already disappeared, only an occasional crunch showing where he was. Is he inhuman? Rodney thought, as a branch of rosemary reached out and tried to trip him up. People aren't meant to see in the dark. He paused for a moment, mentally adding 'device to allow people to see in the dark' to his 'things to invent' list. It was in position number twenty-seven.

A bell sounded at the gate, then sounded again a second time. In the silence that followed, Rodney imagined the clash of weapons and the clinking of hideous implement of torture. The only weapon he had was the knife he used to sharpen his pen. Should have sent Kavanagh, he thought. Saving your master's life at the cost of your own should count for at least three destroyed volumes, he thought.

But Rodney walked on. He wasn't quite sure why. Sheppard had moved easily past the knot garden and onto the front sward. At least that was free from obstruction, and quieter still. Rodney had removed his mother's cherished peacocks only two days after his father's death. He felt less guilty about that than about many other things. It was impossible to create marvels with the infernal creatures screaming away.

The bell sounded a third time. The gate seemed paler than the surrounding darkness. Sheppard had disappeared completely, and whoever was outside knew how to keep to shadows, because Rodney couldn't see them, either.

"Hoped it would be you," Sheppard said suddenly, his voice sounding different, as if everything was sunnier than it had been until now.

"Course it is, Sheppard," said an answering voice from outside. "You going to let me in?"

Sheppard had somehow managed to snatch the key to the gate; Kavanagh always did leave it out on full view on the kitchen table, for any passing rogue to take. He turned the key in the lock and slid back the cunning bolts. Rodney tried to protest, but couldn't muster sound. He thought of the flying machine; of visitors in the house that for two years had seen nobody but himself and Kavanagh, and the slow passage of a wasted life and unjustly disappointed dreams. Sheppard had found a way to thwart the decree of the Queen, and that meant… That meant…

That meant that the man was crazy, with a death-wish. That meant that if Rodney harboured him here… if he touched the flying machine again… if he worked on it, when working on such things had been expressly banned… If Rodney…

The gate swung open, and a cart came through, with a large man driving it. Rodney peered anxiously behind him, but he came in alone. As soon as the gate was locked again, the man swung himself down from his seat. He was enormous, and Rodney found himself edging back a step, deeper into the darkness. "Got yourself hurt again, I see," the man said, even though it was dark enough that surely the blood had to be hidden.

Sheppard gave the quiet laugh of a man at ease, whose confidante and comfort had come. Rodney edged back another step. He should have brought his cloak, he thought, because the night was so very cold.

"It's not too bad," Sheppard said, shrugging. Then he turned to the place where Rodney was standing, thinking himself hidden entirely by the darkness. "This is Ronon Dex," he said. "It seemed wiser to let him in - less chance of unwanted attention that way."

His tone seemed to imply that Rodney was being invited to say something. Rodney frowned; pressed his hands together. "Oh," he said. "Oh, yes. Er… Come in. Uh… since you seem to have presented me with a fait accompli…" and it would be useful to have a big, strong man to fetch supplies and to heft around the large wooden frame of the flying machine and to carry Sheppard around if he went and fainted again and to fight off anyone who came to kill them and to turn the spit so that Rodney could actually have roast hog once in a while, with apples and crackling, "but if I get killed for harbouring fugitives," he said, "count that invitation as rescinded."

"We will," Sheppard said, his voice still light with the happiness engendered by Dex's arrival.

What have I done? Rodney thought, as he walked with them back to the place of his exile. I am so going to regret this.

But the crescent moon shone down on the house, and it looked almost pretty in the faint silver light.

******

This is a sketch of Rodney Manor, as it was in 2004. Rodney Manor was not, of course, its original name, but was the name given to it by its most famous owner, Doctor Rodney McKay, who inherited it from his father in 1553. It was sold to the National Trust in 1943, and can be viewed by the public at any reasonable time. Strange scorch marks are visible in unexpected places, and the more sensitive (or, perhaps, gullible) claim to be able to hear the ghostly voice of a former inhabitant, chiding them for interrupting his very important work, and wheedlingly asking for "some of that new-fangled chocolate."

******

Chapter two

In which it is decreed that everything is Sheppard's fault

__

Ronon closed the casement as quietly as he could. The room was unpleasantly cold, his breath frosting in the air of the early morning. The hearth showed no trace of recent fires, and a thick layer of dust clung to all the surfaces.

"I prefer it open," he heard Sheppard say.

Ronon smiled to himself at the confirmation that Sheppard was awake. "It's better for you like this. Your breathing's going to be bad enough with those ribs, without catching a chill."

Sheppard hadn't completely closed the curtains around the bed, either. He never did, on those rare occasions he had a proper bed to sleep in. Ronon knew better than to question him about it; if he'd endured what Sheppard had endured, he thought that he would fear enclosed spaces, too. But if Ronon never questioned Sheppard's need for open spaces, Sheppard never questioned Ronon's desire to grasp any chance of warmth that presented itself, and to treat a night in a snug room as a gem beyond price.

"It's easy for you to say." Sheppard's voice was quiet, the sounds only slightly dulled around the edges. "You're not the one forced to stay awake in it."

"You know it's necessary." Ronon pulled up a stool, as thick with dust as everything else in the room. Sheppard knew as well as Ronon did that a man could fall asleep after hitting his head, and never awaken in the morning. They had both watched over each other in similar vigils in the past, shaking each other awake through all the watches of the night. "Besides," Ronon said, stretching out his legs, "we should make the most of it while it lasts - a proper house like this, a good one."

"Not such a good one." Sheppard shifted on the pillows. Even the bed-curtains were thick with the musty smell of dust and neglect. "I'm thinking McKay doesn't get many visitors."

"He took us in, though," Ronon said.

Ronon had privately considered it a fool's errand, but Sheppard never saw reason when his beloved flying machine was concerned. He'd proposed the desperate journey in the sluggish, lurching machine, but there was no room in it for two. Just as he always did, Ronon had helped Sheppard drag the machine to the top of a hill and had helped launch him off it, his breathing taut and lurching as the machine sank, then stuttering back to its regular rhythm when Sheppard caught the air currents and started to fly.

One day, he thought… One day… No, he wouldn't think about that. Tomorrow would come when it came, and there was no point worrying about things you couldn't change. Not even God and all his angels could keep Sheppard from trying to fly, and if you were a true friend of his, you just had to accept that.

"I knew he would," Sheppard said. All Ronon could see of him through the crack in the curtains was his hand on the coverlet. "They destroyed his work, Ronon. They took it away from him. That had to hurt."

Ronon was always one step behind, always following. He tried to follow Sheppard's route on the ground, but Sheppard's route was one that ignored hedges and ditches, rivers and cliffs. Sheppard could only fly at night, but even so, some people heard the sound of Ronon passing in the darkness, and came out to investigate. He'd had some near misses. He sometimes wondered if Sheppard knew, or even if he wondered.

"So what now?" Ronon asked. "If this McKay fixes your machine, what happens then?"

Sheppard's hand was still, then it slowly curled into the coverlet; after seven years together, Ronon could read Sheppard from such signs as this, without needing to see his face. "Nothing," Sheppard said. "We carry on like we've carried on for the last two years."

Ronon said nothing, tracing patterns in the dust with his finger. Birds were singing in the garden, greeting the dawn.

"Or that's what I intend to do," Sheppard said, his hand uncurling, deceptively relaxed.

Ronon smiled sadly. "You should know not to say things like that."

In the first few terrible months of Queen Mary's reign, Sheppard had tried to send Ronon away almost daily. 'I refuse to let you go down for what is, after all, my obsession,' he had said one night, when dreams and darkness and cheap ale had made him uncharacteristically honest. Ronon had told him in no uncertain terms that he wasn't going anywhere; that it wasn't anything to do with indebtedness, not any more. Sheppard had saved Ronon's life seven years before in the English Middle March, but Ronon had since repaid that debt in full. But some things went far deeper than honour. Sheppard had come to understand that, or so Ronon had thought. It had been nearly a year since he had last stressed to Ronon that he could leave at any time.

The patterns in the dust were in the shape of a hangman's noose. Ronon wiped them away with a swift sweep of his hand. "I was just wondering…"

"Nothing's going to change," Sheppard said sharply. "McKay fixes my jumper, and we fly off into the sunset." He gave a quick breath of laughter. "Into the wilderness, if you prefer, to sleep on the cold, hard ground, and shun strange company."

Ronon let out a slow breath. If that was what Sheppard wanted, then Ronon would follow him. It wasn't such a bad life, after all, and better than the life Ronon had lived before he had met Sheppard. But, although he might not realise it, Sheppard was a man who needed a cause, and for years he had been without one, his life about nothing more than staying alive and snatching moments in the air. Too many more years like that, Ronon feared, would be a slow death for him.

******

A whole day passed, and nobody turned up to bloodily slaughter Rodney for housing dangerous fugitives, or even to drag him away for hideous torture. He counted these as promising developments. Also, Kavanagh remembered to cook stuffed fowl, and even refrained from adding lemon balm to the mix. Lemon balm was probably preferable to hideous torture, but sage and parsley stuffing was better than both.

The flying machine had been moved to the stable, with Rodney supervising, and Dex, Sheppard, the horse and the cart doing the unimportant part of the job - to whit, the actual transporting. The machine had looked quite horribly broken in the unforgiving light of morning, and Rodney had stood staring at it for a full few minutes, before he had realised all over again quite how infuriating everyone around him was, and had shouted at them for a full few minutes more.

It looked even worse in the stables, amidst the dust and decay. It was nearly two years since Rodney had sold his father's horses to buy lenses, mercury, and a replacement edition of Master Copernicus's entirely obvious theory, that Rodney himself could have come up with when he was six, had it occurred to him that anyone was so stupid as to need such an obvious idea explained to them, and… He frowned, suddenly wondering where his thoughts had been going before Copernicus had come along. Oh yes, dust and decay, and a still-lingering scent of horse, although 'scent' implied a pleasant smell, and this was far from pleasant. Besides, Kavanagh hadn't known which end of a horse was which, and Rodney had dismissed the groom and the stable lad in order to fund the purchase of the materials needed to make a heliocentric armillary sphere, so it had been entirely right to get rid of his father's horses, and…

Something large and animal-sounding stirred in a stall at the far end. Rodney's heart started to pound before he remembered the alarmingly-large Dex and his alarmingly-large beast. "If it crushes my flying machine…" he shouted over his shoulder, throwing the words like spears at the heads of his enemies.

"It won't," Dex called back. His voice seemed to come from high up. Of course, Rodney reminded himself, he was tall. Then a casement slammed shut, and he knew that the giant had been upstairs.

There are people here, he thought. People in my house. It had often been full of people in his childhood, of course, with feasts and dance and music. Rodney had hidden himself away for the most part, barricading himself in his chamber to work on insightful treatises that set his tutor a-stammering and a-stumbling, left behind like a fish beached by the retreating tide. How many years, he wondered, since…? No, no, that didn't matter, just as it didn't matter that there were no tapestries left, all sold to buy books, or that the fashionable furnishings of the parlour had been traded for astrolabes and alembics. It was better that way. Life was better that way.

A door opened, and he heard the sound of two people crunching over gravel. "You well enough for fencing practice?" he heard Dex say. "I'll go easy on you."

"It shouldn't be called fencing," Sheppard said, "not the sort of thing you do. Fencing's elegant, according to the Italian masters. It follows strict rules." The gravel crunched in a way that suggested that he was acting out some ridiculous fencing move, like court gallants and foolish little boys the world over.

"My way's effective, though," Ronon said.

"Yeah," Sheppard agreed, with a quick laugh, "and I've never been one for following rules." Then, after a pause, he said, "I'd better not. It's still…" He didn't say what it was still, though, and Dex didn't ask, so he probably knew.

The horse… whinnied, neighed, snorted, huffed, or whatever it was that horses did; Rodney knew little about horses beyond how to fail to mount them. Outside, twin footsteps sounded, heading away. "Be quiet out there!" Rodney shouted, fury twisting sharply in his chest. "Trying to work, here."

Dust trickled from the eaves above him. Rodney remembered his father striding through here, flushed from his ride and swelling with pride in his horses. Then he looked at the broken wreckage of the flying machine, the last surviving relic of his best, his most accomplished work.

"Can you repair her?" Sheppard asked quietly from behind Rodney's right shoulder.

Rodney started. I thought you… Anger followed, of course. "You shouldn't creep up on me," he snapped. "It's most ill-mannered. I could have been engaged in intricate work in which the slightest lapse of concentration could make the difference between success and disaster."

Sheppard shrugged an apology that didn't really look all that sincere. His attention was all on the wreckage, strewn and broken on its bed of old straw. "Can you repair her?" he asked again.

Rodney's mouth tasted of stable dust. "Of course I can," he said. "I'm Doctor Rodney McKay. I can do anything." The words sounded disappointingly hollow in the bleak stable. Rodney walked forward; Sheppard followed him with his eyes. "The crash merely damaged the wooden structure," Rodney said, "so that's repairable, although a master carpenter would do the job better than I could." He broke off; cleared his throat. "That is to say, it's a job that requires no more skill than a mere artisan possesses. The true genius lies in the design, not the physical construction."

"Ronon and I have some passing knowledge of carpentry," Sheppard said. Rodney looked at him in surprise, for the few things he remembered about the Sheppard family made it exceptionally unlikely that a son of theirs would learn such common crafts. "Necessity," Sheppard said flatly.

Rodney returned to the wreckage. "The problems you were having before the crash…" He straightened his doublet, and stood a little taller. "As you probably don't know, being a scion of nobility, educated only in hitting people over the head and waggling your elegant legs in a gay galliard, all flying machines before mine have failed to launch at all, or else have come crashing precipitously to the ground like Icarus. My secret - my spark of genius, if you like - was to study how the things that do fly fly."

He faltered fractionally over the sentence construction, mentally resolving to rephrase that part of it when he wrote his memoirs. Sheppard, he noticed, was failing to look suitably attentive. His eyes were fixed on the wreckage, but his expression was blank and still, as if a wooden mask had been clapped over his face.

"Air currents," Rodney declared, with a snap of his fingers. He snapped his fingers again, and carried on doing so Sheppard finally turned towards him. "And the reason why Doctor Rodney's McKay's Aeronautical Machine, Mark III, stays up and keeps staying up is because I have provided a host of things that can be adjusted to allow the wings to better use those currents," Rodney told him. "Tail fins. A rudder. Flaps in the wings that can opened and shut by the pilot, as conditions demand."

"Really?" Sheppard said dryly. "I hadn't noticed."

"Yes. Well…" Rodney cleared his throat. It was the dust, he told himself, just the dust. "These things are controlled by levers and cranks, and some of them have…" He searched for a more triumphant ending to his sentence, in keeping with the dictates of rhetoric. When the pause threatened to become long enough for Cicero to frown on, he carried on. "Worn out," he finished defiantly.

"But can you repair her?" Sheppard ran his hand over the outside of the boat section, his touch lingering, gentle.

"Of course I can repair it," Rodney snapped. "Improve it, too."

Sheppard's hand stilled. "Improve her?"

"Balloons," Rodney declared. "Doctor Rodney's McKay's Aeronautical Machine, Mark IV. The problem with the Mark III machines… Well, not a problem as such, just an… an area for further development, an… an opportunity, if you like… and not even God and Aristotle got things entirely perfect first time, with all that smiting - God, that is, not Aristotle - and…" He struggled to regain his train of thought. Sheppard's hand was still on Rodney's flying machine, and that was uncommonly distracting. Rodney wanted to slap it away in fury, saying, 'Mine! It's mine!' but at the same time he wanted to swell with pride and delight at finding someone else who obviously appreciated Rodney's genius the same way he did.

"Balloons?" Sheppard promoted.

"Yes. Yes. Balloons." Rodney mimed a round thing with both hands. "The problem with the Mark III machines is that you have to drag them up to the top of a hill to launch them, but I've done experiments--" He broke off. His eyes flickered from side to side, and he hunched his head down into his shoulders. "Of course I haven't done experiments. I wouldn't dream of going against the Queen's prohibition and launching very small balloons off the Cotswolds, with rabbits in little baskets dangling below, and once a kitten, who ended up, or so Kavanagh tells me, alive and well in North Nibley; Tibbs, she was called. I just made notes in a hypothetical sort of manner. Small notes. Little notes. Marginal notes. Just daydreams, written on the wind."

Sheppard looked at him. There were stories in his eyes that Rodney was suddenly sure he really didn't want to know. "Do you honestly think I'd tell?" Then the expression was washed away in a smile. "Balloons?"

"You do repeat yourself a lot," Rodney said, his voice sharp. The world felt suddenly too large outside the stable, and the stable too small. "As I said, and it's purely hypothetical, it should be possible to build a balloon powered with hot air, and to use it to lift the Mark III machine up into the air and then release it, so you can launch it even from the middle of a plain."

"That sounds perfect." Sheppard grinned. "So you're going to do it?"

"Of course not!" Rodney protested. "The Queen expressly forbade… And then there's the materials, the labour…" He tilted his head to one side, making the calculations. Sheppard and Dex could provide the labour, and the proceeds from the second-best bed might cover the materials, although the peddler he sold most of his things to might balk at carrying it away on his back. "Of course I won't," he said. "They'd torture me for sure, and probably even kill me."

"I knew you'd say yes," Sheppard said, still smiling, and Rodney opened his mouth to protest loudly that he hadn't meant anything of the kind, but he couldn't produce the words. They weren't true, anyway, and somehow… somehow Sheppard had known that.

"But I'm blaming you," Rodney said, "when they come for us. You forced me. You held a knife at my throat and you got your tame giant to roar at me, and you forced me to… to cast the fruits of intellect at your illiterate and uncomprehending feet. It wasn't anything to do with me!" he said loudly, in case the Queen's agents were even now hiding under the thin covering of straw. He didn't think they were, but it was always good to be careful, and Rodney was nothing if not discreet.

******

"He plays the lute." McKay paused in the doorway. Although Ronon was the one with the instrument in his hand, McKay addressed his statement at John.

John said nothing. There were times when he would answer for Ronon, but this wasn't one of them.

The candlelight barely reached the door. The pool of yellow showed the bare plaster wall and the stone slabs of the floor. Ronon had grabbed the best light, and was sitting hunched over the lute, plucking a few bars of a song, tightening the pegs, then playing it again with gentle fingers. It had never ceased to amaze John how unashamed Ronon was about showing glimpses of this other side of him, so at odds with the side that he usually showed. Ronon had once openly wept over the death of a horse; John's eyes had remained dry when they had taken his jumper away from him, even though it had hurt as if they had ripped out his very heart.

"You… you play the lute." McKay's voice was hoarse. "I forgot I had it. No-one's played that since…" He broke off. "You shouldn't be sitting there, you know. You've probably done irreparable damage to my research."

John gestured towards the piles of paper he had removed from the chair and arranged on the floor. "I kept everything in its proper pile."

McKay snorted, as if to say that he doubted it. Then Ronon started to play in earnest. McKay listened for a while, his expression strange, then turned and hurried away.

"I didn't know you could play, either, my friend," John said quietly, as Ronon started to sing in French. His accent wasn't perfect, and he stumbled over occasional notes, but there was a huskiness to Ronon's singing voice that set John's throat unexpectedly aching.

"Belle qui tient ma vie," Ronon sang, to the slow air of a pavane. It was a song to a beautiful lady who held his soul captive, without whom he would die. Just a song, of course. Just a song…

John stood up. "I need some air."

Ronon looked up from his instrument and gave a quick smile, his expression entirely at odds with the sentiments he was singing about. John stepped carefully over the piles of diagrams and the scattered plans. He wove around a half-constructed compass, its parts strewn across the hearth. 'A Device to Allow Man to Breathe Underwater, thus Facilitating the Retrieval of Sundry Items from Dangerous Wrecks,' he saw, but although the heading was underlined three times, there was no writing below it.

The music followed him into the kitchen and out of the back door; he had never seen the front door open, although he had, of course, examined its locks, in case they should end up having to defend it. It followed him as he walked to the courtyard, but finally faded away to nothing as he entered the stable. He could see little of his broken darling by lantern light. Stupid, he berated himself, that a lump of wood and canvas should mean so much to you. But it did, of course, and the damage from that had already been done. Too late now to change.

Back in the courtyard, the tune had changed into a wordless one. John could see Ronon through the parlour window, hunched over the lute, his hair covering his face. John had always known that Ronon had originally come from a good Border family, but he hadn't known that he could play the lute or sing in French. Not that Ronon would talk about it afterwards, of course, or treat this as any sort of revelation. Every few months, John added one more page to the book of his knowledge of Ronon Dex. After seven years, it was still a slim volume.

No, he thought. Before even a year had had passed, he had known everything that was important to know about Ronon. He could trust him, and that was what mattered. The rest was… irrelevant, and as unimportant as Ronon evidently considered it.

Extinguishing his lantern, John headed to the greensward at the dark front of the house. His ribs still hurt with every breath, but they seemed to be bruised rather than broken. His head throbbed faintly, but he had suffered far worse in the past. Knowing that his jumper was broken was like having a limb missing. He'd tried to explain that once to Ronon. 'When a horse dies,' he had said, 'you can get another, and while it's not the same horse, it's a horse, and you can still ride as fast as the wind. But this… this is the only one. She's my only chance at having wings.' But he wasn't sure if even Ronon fully understood. Ronon had no desire to leave the ground.

John saw McKay before the other man saw him. He considered creeping away again, but something made him stay. He made his next steps noisier than they needed to be. The moon was several days past its narrow crescent, and it was enough to show McKay stiffen, freeze, then let out an angry breath.

"Can't a man get any peace in his own house?" he snapped. "This is my house, and you've invaded it, you and Dex, and there's music, music distracting me from my work, and now you're following me out here and ruining the only peace I can get."

"I wasn't following you," John said truthfully. "I came out to look at the stars." It was only half a lie; the stars had always fascinated him.

"Hmph." McKay snorted grudgingly. "That's what I'm here for, too, of course. I expect you think they're painted on the heavens every night by God's frilly angels. They aren't, of course. They're fixed to the edge of the universe, to the inside of the sphere that has the sun at its centre. We revolve around the sun, and the stars are the fixed surface around us." He made complicated gestures of a half-clenched fist oscillating in a loosely-cupped hand. People in taverns would make ribald jokes about a gesture like that. John just watched, and his next breath came a little easier than all the ones that had come before.

"One day," McKay said, "I intend to create a device that will allow me to study the stars in more detail. I intend to call it Doctor Rodney McKay's Ingenious Televisual Device. It's twenty-second on my list." He looked up at the stars, and let out a long slow breath. "Perhaps I'll move it up the list," he said quietly. Then, harshness coming hot on the heels of reflection, he rounded on John almost accusingly. "What does someone like you see in the stars?"

"Navigation, for one," John said. He looked at Orion, that bold herald of winter nights. "When I was young," he found himself saying, "the stars made me want to fly."

McKay said nothing, but John heard him breathing, close in the dark. John had dreamed of flying, and McKay had dreamed of making a machine that could fly. That was a bond, in a way, as close as the bond he had with Ronon, although infinitely different. One was the bond of shared dreams, and one the bond of shared lives.

McKay tugged his cloak around his body, looking down from the sky. "Why did you save my fl-- my Aeronautical Machine from being destroyed? What have you been doing with it?"

Or perhaps the bond itself was just a dream - or maybe an 'it' was just a word, just as an irascible exterior could hide many things. "Surviving," John said, answering the easier part, the part that didn't involve opening a window into his soul.

"I wondered…" McKay said awkwardly, "if you were… uh… engaged in plotting and machinations against the Queen."

John looked straight ahead, to a place where there were no stars. "Nothing as noble as that." He gave a wry smile. McKay didn't squawk in protest at his choice of adjective. "I wasn't involved in my lord of Northumberland's plot, you know. And don't start jumping to conclusions. I was too busy flying. It didn't… Nothing else… Nothing else felt as important, you know? But they blamed us all, of course, tarred our names with association." And he'd escaped and stolen the jumper just to keep flying her, just to stay alive. "It was never treason," he said.

"But the Queen's agents won't see it that way." McKay was fidgeting nervously.

"No." John shook his head. Love, it seemed, could make traitors of them all.

"But your father…" McKay began.

John clenched his fists at his side. "Like I said, it's guilt by association." And he hadn't thought that they'd take it so far. No, be honest here, John; you didn't stop to think. Perhaps they hadn't meant to take it so far, either, but his father had always had a weak heart, and the cells in the Tower of London were so very cold.

"How long before you get her repaired?" John's voice sounded brittle in the echoing silence of the night.

"A few weeks," McKay said, "as long as you and Dex stay to handle the unskilled labour. Of course," he said, "the Queen's agents will probably have dragged me to the Tower for hideous torment by then, but don't forget that I'm telling them that it's all your fault. They'll probably believe me, too, with your history."

John thought of his father, the last time he had seen him, the older man's face darkened with anger. Doors had slammed that would never be opened again, that never could be opened again. "Yes," he agreed quietly, "they probably will."

Perhaps the wind changed then, because a faint burst of music came across the sward. It was a song about soldiers broken by war.

"And of course we're staying," John said, because he went wherever his puddlejumper went, and Ronon, it seemed, went wherever he went. They would stay until the jumper was repaired, and then he would fly away, to go with the wind, to live in the shadows…

To survive.

******

end of chapter two

On to the next part

Author: Eildon Rhymer (rhymer23)

Words: c. 50,000, plus 6 pictures

Rating: PG

Genre: AU (also adventure, some angst, some humour, some h/c, and some illustrations)

Spoilers: None

Summary: It started with a man crashing into a herb garden. Soon a misfit band of four exiles are caught up in a wild ride of sword fights, sewing, rescue missions, shopping trips, high treason, lute-playing, changing the face of scientific knowledge forever, the imminent risk of hideous death, and comfits.

Note: Written for the bonus round of the sga_genficathon, in the genre of AU, and the prompt "Those magnificent men in their flying machines". Something about gen ficathon bonus rounds seems to bring out the illustrated historical AU in me. Last year I did The Pirate's Prisoner, and this year I've gone back nearly 200 years to the year 1555. For a prompt about flying machines. Er, yes, well. I suspect that normal people wouldn't see a prompt about flying machines and immediately think "We'll have Tudors! With planes!" but I blame Leonardo Da Vinci. He famously designed flying machines on paper, but didn't get them to work, but he was merely Leonardo; he wasn't Doctor Rodney McKay.

I've tried to explain the historical background as and when it becomes relevant, but a very quick outline can be seen here

******

Chapter one

In which Rodney has an encounter with a mysterious stranger, served with a side dish of herbs

__

Rodney McKay had almost designed the first genuine perpetual motion machine known in Christendom, when an impertinent rogue crashed out of the sky and landed in his knot garden.

Such occurrences did not happen very often in the Year of Our Lord, fifteen fifty-five, the however-manyth year of the reign of Queen Mary, God preserve her, etcetera etcetera. It caused Rodney's pen to snap, flooding ink across the page. Cursing, he reached for his sand-shaker to soak up the ink, but his trembling hand struck the ink bottle and toppled it over. His beautiful designs were eaten by the encroaching blackness. Sand was no use, not against a catastrophe of such magnitude. The dark cloud of brutality and ignorance always triumphed over enlightenment in the end.

Rodney stood up furiously, his chair scraping on the floor. At that point, of course, he didn't know that an impertinent rogue had crashed out of the etcetera etcetera, just that an ungodly noise had come from the direction of his knot garden. He thought it was probably foxes, or maybe badgers, his old nemeses. Whatever it was, it had interrupted his work, and that meant that it needed to be dealt with.

"Uh, deal with that, Kavanagh," he shouted, but there was no answer, and no sound of scurrying manservant rushing to defend his master's life with his own. Of course not, Rodney thought crossly. Kavanagh was a deep sleeper, and it was… Rodney reached for the heavy watch he wore round his neck, and peered at it in the light of a guttering candle. The hand was somewhere between the XI and the XII. So how dare something make a noise in my garden, Rodney fumed, at a time when all decent people are asleep? Part of his mind recognised the flaw in his outrage. He ignored that part determinedly.

Swept along by a carefully-nurtured wave of fury, Rodney reached down a lantern from the kitchen shelf, and lit it from a candle sconce. There were a lot of bolts on the back door, for reasons that had made sense at the time. Outside was chilly, with a sense of huge and endless vistas, full of unpleasant, nameless things. The flame inside the lantern looked very tiny in the vastness that was the world.

"Uh…" Rodney made an inarticulate sound, his mouth suddenly very dry. Maybe it wasn't quite such an unforgivable thing after all, he thought, to ruin his designs for a perpetual motion machine and to cause enlightenment to be extinguished with a dark cloud of brutality, ignorance and ink. Perhaps it could be forgiven and forgotten, if he went back inside and locked the doors and closed the curtains around his bed and lay there very still with his pillows over his ears. Discretion was the better part of valour, after all, so that would be the valorous thing to do, the brave thing, the…

Something stirred in his knot garden. In the light of the crescent moon, Rodney saw an enormous brutish shape rearing up from his rosemary bushes.

The lantern slipped from his fingers and crashed onto the gravel, the glass shattering. It was… uh, a… a tactical decision - yes, of course it was - because the light would have helped his attacker pinpoint his location.

"Who's there?" Rodney bravely demanded. The scent of rosemary was strong and cloying. "You…" Rodney swallowed. The best remedy for abject terror was always fury; it had enabled Rodney to survive things that had felled lesser man. "You're ruining my knot garden."

"It's not a very good knot garden," a voice replied from the darkness. It definitely wasn't a badger.

"But it's my knot garden," Rodney said, suddenly realising that the reputation of his knot garden was more important even than designs for perpetual motion machines that would make him the toast of Christendom, and perhaps even the more enlightened of the heathens. "And you're not supposed to be in it."

The dark shape lurched forward, and the smell of crushed thyme joined the rosemary. As well as abject terror and fury, Rodney was suddenly ravenous for roast fowl, pleasingly stuffed. He swallowed hard, and forced himself to concentrate on the fact that he was probably going to get bloodily murdered so close to his own back door. When had he last eaten, anyway?

"I apologise," said Rodney's murderer. "It… happened. I'd intended a more conventional approach."

Rodney began to back defiantly away. "How did you get in, anyway? I mean, hello? Outer walls with spiky things on them? Impenetrable locks, designed by yours truly? Security impossible to breach? Though the badgers and foxes get in by digging, but I'm working on that. Rabbits, too."

His murderer moved on to crushing sage. "There's another way, of course. I'm thinking that if I've come to the right place, and you're really Rodney McKay--"

"Doctor Rodney McKay," Rodney corrected him stiffly.

"Then you'd know this," his murderer finished, his deadly path hung around with an aura of chives.

Rodney took a few more steps backwards, but his sense of direction was confused in the dark, and parsley joined the fragrant mix. "So, uh, if you were specifically trying to find me, you…" He tripped over a low hedge, and only just managed to avoid falling backwards onto the gravel. "Have you come to assassinate me?" he managed to ask with furious dignity.

The dark shape was still mired down in chives. "Why would I want to do a thing like that?"

"Oh, many reasons." Rodney straightened his doublet, smoothing it down. "I served the late King Edward, and Protector Somerset was my patron, whose name is, of course, anathema to the present regime. I created wonders for his armies, and all those secrets are now forgotten by everyone but me. Why, just this evening, I was on the verge of creating a perpetual motion machine, and I would have done so if it wasn't for you. Unfortunately, the present Queen has no interest in enlightenment, and banished me, would you believe, to this godforsaken backwater in the country, and commanded me to stop my ungodly work. Ungodly, I ask you! People always fear that which they do not understand."

The dark shape was wrapped in a miasma of chives. "You make a tempting case," it said, "but I think I'll pass for now."

A barn owl flew low overhead; Rodney's sharp squawk was one of defiance, of course, and not terror. "Then if you haven't come to kill me," Rodney snapped, "why are you here? You're… you're a dark cloud of brutality and ignorance. You interrupted my work! Work's all I've got left, and you…" He scraped his hand across his face, exhaling sharply. "You interrupted me," he said, "and I don't know what you want, and I don't know how you got here, and things aren't meant to be like this."

"I'm sorry," said the dark shape quietly. "I came for your help, but I lost control. I left it too late. I'm afraid I broke her up a bit."

He stepped forward and became a tall man dressed in black. A moment later, he fainted, crumpling to his side in the parsley and chives.

******

John drifted awake to find someone shaking him. His heart lurched, and he lashed out, memories of dungeons pressing down on him. His hand struck something solid. "No!" someone squawked, and, "Don't!" but John's other hand found his dagger, and he wrenched it out of its sheath.

"Are you crazy?" squeaked the voice. "You said you weren't going to kill me. Oh. Oh. I see. You think…" The voice tried to turn soothing. The feel of the dagger in John's palm was more soothing still. "I'm not going to hurt you. Nice mysterious stranger. Good mysterious stranger. Just, uh, lie still, and, er, do whatever people are supposed to do when they… I think you've hurt your head. It's all blood-stained. You fainted."

"Yeah." John moistened dry lips. "That explains the regiment of drums pounding in my skull." There was more, too, but he had long-since learnt not to show weakness when it wasn't necessary. He tightened his grip on his dagger. He knew where he was, of course, but the memories circled like carrion crows, still too close for comfort. The dagger helped.

McKay was standing over him, a lantern trailing from one hand. "Ow," McKay said pointedly, when he saw John looking at him. His other hand rubbed his shoulder, thumb massaging the collarbone. "It's quite impolite," he said, "to break into someone's knot garden, faint in their parsley and then attack the person who's trying to prod you back to life again."

John managed to stand up; he had never liked being on the ground when other people were standing. Everything swayed, but it was nothing he couldn't deal with. The memories that had resurfaced upon awakening had quite driven away the temptation to bait this man. "I need your help," he said wearily. "My puddlejumper's broken." Then he glanced over his shoulder, covering the twist of pain with a wry smile. "More than broken now, of course. I need you to fix her. Please." His voice cracked; he hadn't meant it to.

"Puddlejumper?" McKay echoed, frowning.

John gestured weakly in the appropriate direction. He tried not to shift uncomfortably as McKay slowly walked away, taking the light with him. In the protection of the darkness, his hand rose to his brow, feeling blood on the side of his face. Even when he touched it gently, pain flared throughout his skull. His silenced gasp of pain caused an answering stab of pain deep in his ribs. Pressing his forearm across his middle, he watched the lantern bob through the herb garden. Of course he had to let McKay see her. Of course he had to let McKay touch her. It is kind of the point, John.

"It's probably a trap," McKay was muttering. "You've got an accomplice out here in the potager. I'm armed, varlet! I'm a skilled fighter, h-hiding my light under a bushel. I've killed dozens of rogues. I'm--" His voice broke off. The lantern went very still. John counted slowly to twenty, and still McKay didn't move.

"But they destroyed them all," McKay said at last, his voice very different from anything that had gone before. It sounded as if all masks had been stripped away from him, and this, this, was the real McKay. "The Queen had them destroyed. All of them. There were none left."

"I guess she didn't get all of them." John tried to keep his voice light, but it caught on the last word.

"How?" The lantern swung round, and came back, swinging from side to side.

"I escaped." His words were quiet in the vastness of the darkness. He pressed his arm tighter against his body, fingers digging into the flesh of his side. "I grabbed the jumper and got the hell away from there. The Queen's men couldn't stop me." The darkness was thick with memories. He spoke over them with a level voice, and refused to let them come out to play.

"But that was almost two years ago," McKay said. He was close enough now for John to see his face. John turned his own face slightly to the side. "How have you kept this a secret for so long? What have you been doing?"

John shrugged. "I keep my head down."

"But how…?" McKay began. John heard his feet crunching on the gravel, and he clenched his fist tightly at his side, fingers digging into his palm. "Why didn't I know about it? I invented the things. I have a right, you know. They're mine. The first functional flying machine in the whole history of the world outside the realms of silly legends. People talk about the great Signor Da Vinci, but his were just paper plans, deeply flawed. I, I, Rodney McKay, Doctor Rodney McKay, was the first person to make flight possible, and the Queen burned my machines and banished me and said that my creation would be expunged from the annals of history forever more, when it should be sung to the heavens and glorified."

"I remembered," John said quietly. McKay's ranting made the horrors retreat even further. He focused on the pool of lantern light and the sweetness of the crushed herbs. "She's not been working so well lately. I found out where you lived and came--"

"And why do you call it by that ridiculous name?" McKay demanded. "The correct name is Doctor Rodney McKay's Aeronautical Machine, Mark III. And you've broken it. The only surviving proof of my dazzling accomplishment, and you've broken it."

John turned towards the wreckage hidden in the darkness. "I'm sorry," he murmured, and then the darkness took him again.

******

There was nothing for it, of course, but to drag Kavanagh out of bed. "There's a man in my parsley," Rodney told him. "He's fainted. I believe that the usual course of action would be to bring him inside and put him by a nice warm fire." Kavanagh just blinked at him. "So jump to it," Rodney commanded.

They had to do it together in the end. Quite a lot of herbs were irredeemably crushed. "Which reminds me," Rodney gasped, hefting the mysterious stranger's limp legs, "I would like roast fowl tomorrow, with parsley and sage stuffing, and no lemon balm this time, or my wrath will… indeed be… terrible." He dropped a leg. Kavanagh grunted, but managed to keep the man's top half off the ground. Rodney managed to grasp the mysterious stranger's leg again. He had the irritating leg of a courtier who liked to pose for portraits in too-short breeches. He was slim beneath his doublet, too. Ladies would doubtless swoon at his feet. Rodney decided that he disliked him intensely.

"Who is he?" Kavanagh asked, staggering on the gravel. "How did he get here?"

Sometimes if you ignored a question, it obligingly went away. "Concentrate on… getting him… inside," Rodney gasped. Carrying an unconscious man was harder than it looked. The dashing soldier types with their shapely legs had made it look much easier than this, when Rodney had cowered… that is, when Rodney had maintained a tactical vantage point behind the baggage train during Protector Somerset's campaigns against the Scots. Of course, military types were all about show, and doubtless thought that Euclid's Elements was a salve for boils, newly introduced from Italy.

"What's wrong with him?" Kavanagh asked, as they crossed the threshold.

Rodney contemplated stairs, and the effort needed to lift an unconscious man onto a bed. "We'll put him in my study," he said, "on the floor… next to… the… fire." It was probably better for him, anyway. Elevation would… something something… detrimental to his injuries… things like that.

When the mysterious stranger was safely dumped… that is, safely placed on the rug, Rodney straightened a weary back and flapped a weary hand. "Get… what we need."

Kavanagh still looked half asleep, clad in a crumpled robe. "What do we need?"

"Don't you know?" Rodney expressed the appropriate outrage. "I thought you wanted to be called a student of natural philosophy. That's what you told me, anyway."

Kavanagh had come to Rodney as his apprentice, his acolyte, his disciple, his minion; Rodney changed his mind from week to week about which title was the most gratifying. When an unsupervised and unauthorised investigation into the principles of combustion had resulted in the loss of twenty-seven priceless volumes from Rodney's library, Kavanagh had been demoted to manservant until the debt had been paid off. Since the books had been priceless, Rodney calculated that Kavanagh would be serving for the whole of eternity. Fortunately arithmetic had never been Kavanagh's strength, and he accepted his term of durance. Debtors' prisoners were worse.

As Kavanagh rummaged noisily in the kitchen, Rodney went to his shelves and took down a slightly charred volume. Kneeling beside the man, he leafed through the book with a weary hand.

"What you reading?" the mysterious stranger mumbled.

"Oh, now he wakes up!" Rodney cried. "You could have woken up when we carried you in from the garden. I think my back's ruined forever."

The mysterious stranger gave a faint smile. "I thank you for sacrificing your future health for my sake."

"Well…" Rodney cleared his throat. "It wasn't really for your sake. I can't have you dying on me, not if you're the only person anywhere near here who can actually fly one of Doctor Rodney McKay's Aeronautical Machines, Mark III. They used to tell me it took extraordinary skill. Not as much skill as inventing the things, of course. I mean, all you have to do is sit there and pull a few levers."

Firelight flickered on the mysterious stranger's face, filling its hollows with deep shadows. "Fly them yourself, do you?"

"God's blood, no! What do you take me for?" Rodney stopped, smoothed down the open page, straightened his doublet. "I could, of course, but…" He swallowed; tried to think of the correct words to express his tactical decision to contribute to Protector Somerset's flying project at a discreet distance.

"Yeah," the mysterious stranger murmured, smiling again. "I get it. Only a crazy person would jump off a hill, entrusting his life to wood and canvas. You have to find the air currents, like birds do. You get a sense for them. You learn how to manipulate the propellers and flaps to use them best. Crazy." His eyelids began to flutter shut.

"Oh. Oh. You're not getting delirious, are you?" Rodney leafed faster through the book.

The stranger's eyes opened again. "What's the book?" he asked again.

"Vesalius," McKay told him proudly. "De humani corporis fabrica. Not the abridged version, either, but the full seven volume set. Of course," honesty compelled him to add; he was admirably fair-minded when it came to admitting other people's errors, "my idiot manservant caused most of the volumes to be destroyed by fire, and all I've got left is volume six." He turned to the title page. Volume six was apparently about the organs of digestion and reproduction. He closed it casually, with the air of someone who had learnt all he could from it. "Books contain wisdom," he said, because you had to explain things to illiterate people of lesser intellect. "It'll allow me to repair you."

The mysterious stranger managed to turn his head so that almost no light fell on his face at all, despite his closeness to the fire. "Repair my jumper instead," he said. "I'm good."

Rodney pushed the book away, sliding it across the floor. There was little that the master of anatomy could teach him, after all. It was out of date, anyway; Kavanagh had come back from Oxford with reports of a second edition. Kavanagh, bumbling fool that he was, still had contacts. Rodney had lived barely a dozen miles from the university for almost two years, and not one single person had sought him out. This stranger, Rodney realised, was the first guest that the house had seen since his father had died. His father had survived only one month of Rodney's banishment. His last words had not been kind.

"For the last time," Rodney said crossly, "don't call it by that ridiculous name." He stood up and went to shelve the book. His hands were shaking, fumbling with the volumes. Kavanagh was silent now in the kitchen. A faint scent of herbs still clung to Rodney's clothes, and Rodney suddenly remembered his childhood, and his mother's smiling delight in her new-style garden. He tended it whenever memory struck him. Most of the time, though, he considered it stupid.

The stranger was watching Rodney when he turned back, and unlike many people that Rodney had known over the years, he made no attempt to hide it when he realised that he had been discovered. That made Rodney feel… Well, he wasn't quite sure what it made him feel. "What's your name, anyway?" he demanded harshly.

The stranger nodded, giving an imitation of a bow that was surprisingly effective for someone lying on their back with blood on their face. "John Sheppard, at your service."

"That would be Sir John Sheppard, then," Rodney said bitterly. The late king had thrown knighthoods at all his pilots, despite the fact that they were expendable fools. Rodney, by contrast, had received only grudging acceptance, and many of the courtiers had been quite unforgivably rude. Then he frowned, struggling to remember. He'd never bothered to make the acquaintance of the thrill-seeking idiots who'd flown his precious creations. The moment the six machines had been put into active service, Rodney had already been closeted in a series of chambers, working on Doctor Rodney McKay's Aeronautical Machine Mark IV. It involved balloons. "Are you any relation of--?"

"He was my father," Sheppard said, in a tone that even Rodney could recognise brooked no argument.

"Oh." Rodney swallowed; moistened his lips. "Weren't you, uh, arrested?" All the pilots had been arrested; he remembered that now. The Duke of Northumberland had used several of Rodney's flying machines in his attempt to put his daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey, on the throne of England instead of the present Queen. Whether guilty or not, the whole lot of them had been accused of treason. It was the loss of his beautiful machines that had filled the first few months of Rodney's exile with rage and despair, and the withdrawal of patronage that had made the next two years cold and bleak and empty, but people had died - less important than any of that, of course, but, still…

"I got away." Sheppard's face was a closed door. The room felt suddenly colder.

And hadn't his father…? Rodney pressed his lips together. Kavanagh would know; he relished tales of execution and the fall of great lords.

As if summoned by his thoughts, Kavanagh entered the room, a bowl of warm water steaming in his hands and a towel draped over his arm. "There's someone at the gate," he said, his eyes flickering between Sheppard and Rodney.