Shamans and Food Stamps: Authenticity, Reality, and the Ethics of Rewilding

[Note- drafts of this have been shown to friends for the last week. THIS IS THE FINISHED VERSION! If you haven't read a draft of this essay with this header, you haven't read this essay. Thanks!]

While looking for a book on kayaking, I came across Jon Turk's The Raven's Gift: A Scientist, a Shaman, and Their Remarkable Journey Through the Siberian Wilderness. The subtitle mentions a "shaman" which is a +1 Word of Cheesiness and sure enough, the book is disappointing. Like most things on this blog, though, it also connects nicely to a larger question that's been turning over in my head for a while, and provides a bit of insight even as I choke over the hokier parts.

Jon Turk, the author, came to prominence with his earlier book, an arctic kayak travelogue titled In the Wake of the Jomon:Stone Age Mariners and a Voyage Across the Pacific. In it, Turk took inspiration from a spurious identification of the 9,500-yearold Kennewick Man found in Washington State as ethnically related to the Jomon, a prehistoric Japanese culture, and set out to prove that early Americans would not have had to rely on the (intermittently submerged) Bering Land Bridge to cross back and forth from Asia. Without getting too deep into the Clovis-first debate, indigenous scholars have been arguing for years that paleoindians were sophisticated enough to island-hop, while European archaeologists have claimed that the migration happened only once or only rarely, and depended on a very lucky series of coincidences to make it to what is now the mainland US.

Turk's 2000 voyage had the potential to be a Kon-Tiki-like proof of concept, but a number of workarounds undercut the validity of his effort, and critical archaeologists have little difficulty ignoring him. DNA analysis was never completed on the Kennewick remains, and the book, while available on google books, is not the one I'm reviewing today.

Raven's Gift opens midway through the first story. Turk and his Russian pal Misha have landed their kayaks on the Kamchatka peninsula in a storm, and are welcomed by a group of Koryaks who give them food, a place to stay, and a quick tour of the town of Vyvenka. Turk makes the brief acquaintance of an old woman he names Moolynaut who is a shaman and invites him back. Over the next few years he returns several times, undertaking or attempting quests for Moolynaut including locating "free living" reindeer herders not forced into cities by Soviet deracination, skiing to the Chukchi peninsula, and of course, taking lots of mushrooms. Throughout, he chases Kutcha the Koryak raven figure, and bewails his childhood imprisonment in a world of left-brain thinking. Eventually his wife dies.

The problem is that I don't believe him. I don't think he's faking, but he may be embellishing a lot. He mentions financial troubles after Jomon crashed and burned, one can imagine this book as a way out of a publishing contract, or debt- what editor, after all, will fact-check with a group of harried indigenous Russians living in Siberia? But I can fact-check on the internet, and the comparison doesn't flatter him. For instance, the Koryak raven spirit isn't Kutcha, its Quikil or Quikinnaqu. You could conceivably mistake the one for the other, and Turk is a lousy linguist whose transliteration of "visdichot" (for Russian:vezdekhod) was so impermeable I had to find a native speaker. Still, there are other problems.

In one scene, Turk describes picking a "wild cranberry" off the tundra and eating, savoring the sweetness. Does he mean a cloudberry? Or are wild cranberries in Siberia that different from every wild cranberry I've every eaten? Similarly, he both identifies and describes his "mukhomor" as Amanita muscaria (indeed, krasniy mukhomor is the Russian name, though the Koryak word is wapaq) but somehow fails to mention any of the well-known side effects when describing his mushroom trips. His characterizations of the Koryaks he meets are entertaining and well-realized, but once he drops past personal history into describing Koryak legends, belief, or history, he falls flat. The account of the Soviet collectivization campaign is repetitive and weirdly non-specific: he cites an apocryphal story about "Russians throwing shamans out of helicopters to see if they could fly," which the Soviets may well have done somewhere, but probably not during the 1931 creation of the Koryak SSR, since the first helicopter from which a shaman could have been thrown wasn't built until 1941.

I compare Turk unfavorably to Canadian Farley Mowat, whose Ihalmiut sequence (People of the Deer, The Desperate People, No Man's River and the cataclysmic sixty-year update Walking On the Land) still sets the standard for out-of-place-honky-writes-about-colonialism books. Although he is the "scientist" of the title, Turk's career as a research chemist ended in the sixties and he might more properly be termed a "writer of scientific textbooks and amateur adventurer." This book is clearly located in the adventure memoir genre, and despite his claim to being a "travelling storyteller" Jon Turk is dreadful at telling stories. He never gets inside the heads of his characters, never anticipates the reader's questions, and seems almost baby-like in his indifference to his own motivations in leading a life of Extreme Sports Adventure. Turk is like a bad date, who not only always talks about himself, he doesn't even have anything insightful about himself to say.

Some Dubious Romantic "Other" Books

It is enlightening to put Raven's Gift on the same shelf as Marlo Morgan's phony Mutant Message From Down Under, Isabel Fonseca's clueless Bury Me Standing or Eric Brende's dubious Better Off. Like them, a westerner seeks out an Outsider culture, incorporates into them for a period of time, and returns with a number of romantic insights on his or her own culture, all of which are easily challenged by both in- and out-culture scholars who have to spend a great deal of energy dissuading thrill seekers with boring tales of assimilation, stress, linguistic approximation, and, of course, the Roma words for all those concepts Fonseca claims the Roma don't have words for. Its worth noting that both Brende and Morgan specifically place their out-culture contacts in a "secret" location, where mainstream ethnographers never go- this is echoed in Turk's pilgrimage to find "untouched" reindeer herders. Its the new-age ethnography equivalent of What These People Need Is A Honky- its, What This Honky Needs Is A Pre-Contact People.

Now for the serious essay question: Why do these books keep getting written? What is it that draws American readers to doubtful yet utopian travelogues about pre-technological others? I think the reason (and so many other reasons as well) comes down to the romantic (and, in American culture, ubiquitous) conflict between the Authentic and the Real.

A few definitions first- the Real is more or less lived experience. I woke up today, put on cotton canvas trousers, walked the dogs, ate some oatmeal, sang a few stanzas of a Johnny Cash song to myself, called my work... etc. The details differ from day to day, person to person, but I imagine that most readers here had mornings that are, in terms of cultural valuations, the same. The Authentic is the idea of what a morning *should* be, if impediments were removed. Maybe mornings aren't such a good example- lets take Easter.

Real Easter goes like this: chocolate candies, and jellybeans, primarily egg- and rabbit-themed, show up in stores. People bag and basket them up for children. Decorations appear in non-strictly-secular environments that use lots of pastel colors and tulips. If you are Christian, you might go to church, quite possibly for the first time since Christmas. Kids get a week off school, though this may be a coincidence. (A more common history says spring break was time to help the family plant crops.)

Authentic Easter has a lot more to do with Jesus and crucifixion and redemption, a week of sorrow followed by a day of feasting. Authentic iconography involves capital punishment and graves. The difference drives Christians crazy. Some commentators, of course, will blame the media, and others will blame the schools. Most will place Authentic Easter in a semi-historical past that has been "lost" in the "modern age."

You can play this game with almost any holiday, but the pattern extends beyond the "secularization" of the calendar. Recently, Salon ran an article about "Hipsters on Food Stamps"- kids with educations and previously prestigious work histories, losing their jobs and claiming public benefits. What put online commentators in high dudgeon (oh who are we kidding, they live there- what they CLAIMED they were upset about) was that the hipsters were buying high-status foods like organic vegetables with their food stamps, instead of commodity cheese and cheerios. Nobody seemed to be able to articulate why an out-of-work graphic designer with two kids should be less deserving than an out-of-work steamfitter with two kids, nor was anyone arguing that poor people should be forced to eat unhealthy food. Still, it pissed people off like nothing you've ever seen.

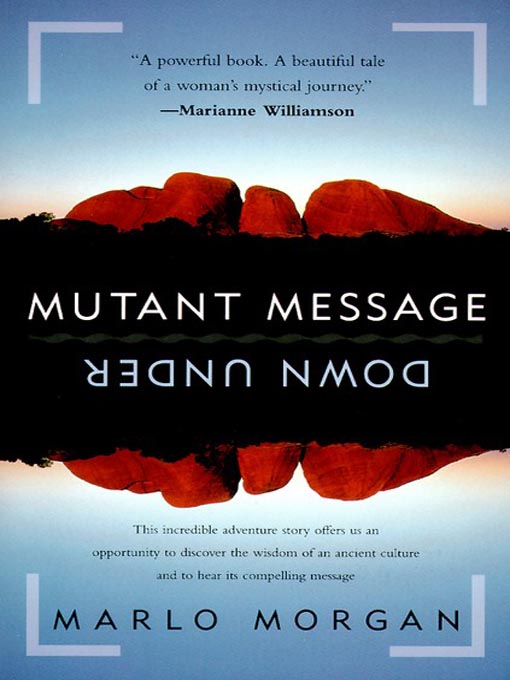

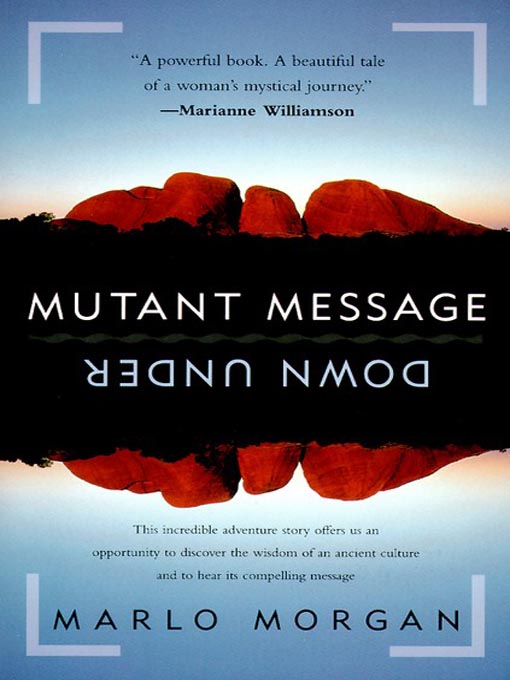

The problem, of course, is that while the real category of poor people includes hipsters, the Authentic poor do not. Authentic poor Americans look like Florence Owens Thompson as photographed by Dorothea Lange in 1936:

Real poor Americans look like Florence Owens Thompson as photographed by her family in 1979:

Authenticity, in other words, is the cultural narrative we tell about how things should be. Very rarely does this coincide with how things are. The hipsters in the story, while real, were inauthentic, and therefore should not have been poor, or been treated as equal to authentic poor benefits recipients. Inauthenticity is the site of a great deal of cultural control in a variety of realms- consider then-governor Jesse Ventura's snarled 1999 promise to recognize tribal fishing rights only if Indians fished "in birch bark canoes." Despite being ridiculous on face, appearing authentic can be an obligation for out-groups in American culture, and its absence is used as a pretext for further disenfranchisement.

Nonetheless, Authenticity is percieved, at least in the Western imagination, to be lurking around the corner, in the next neighborhood, in the recent past, in the pre-contact indigenous- always just out of reach, but close enough to strive for. Dreams of authenticity are often displaced onto the poor or "working class." The Republican Authentic world, with its small towns, stable jobs, long-term monogamy, ethnic homogeneity and universal christianity, is perceived by Republicans to inhere in the Joe Plumbers of America, even if they (the Republicans, or for that matter any Joe Plumbers who make it onto TV) can't embody its ideals themselves. The Democratic Authentic world, with its convivial cosmopolitanism, fair deals for workers and neighbors, and chicken gardens, is similarly the province of Joe Union, even if this doesn't line up with reality either. Reality, for both parties, has a lot more suburbs and divorce, cheap beer, scandals, and ennui. But these are post-lapsarian, conditions of the fall. Vote for me, say the candidates, and we will return to the way things ought to be.

The debate between Reality and Authenticity has a strong parallel in the Eden legend- everything was great, then it got broken- and terms like "post-lapsarian" are entirely appropriate. However, its important to realize that the debate itself is a cultural narrative- one could, after all, recognize the suburban/divorce model of culture as the actual way American Humans live, without ever positing some other way that has been lost- and that as a narrative both sides are supremely contemporary, and also inherently reactionary. Inherently reactionary because if you argue too strongly for the Real, and you end up stagnant, recreating the same damn cut-out paper bunnies every year, but if you argue too strongly for the Authentic and you end up expelling the interlopers from your homelands.

Supremely contemporary because stories about the life we're being kept from- by secularism, by the spectacle, by decadence, by technology, by too much left-brained thinking- are just that: stories. Not just stories, but modern stories, rewritten every generation. The Authentic world is every bit as much of-the-moment as the cell phones and block scheduling we perceive as impediments to reaching it. By looking at our quasi-historical, or quasi-geographic vision of "how things used to/ought to be," what we in fact see is something about how things really are in our hearts. Which is what brings us back to Mr. Turk and his book (did you remember this was a book report?) and another subject dear to my heart- apocalyptic neoprimitivism.

(That's Jon Turk, by the way- I can't bring myself to dislike him)

There is a strain of thought, lets call it "rewilding," that believes the path to Authenticity is through anthropology, specifically paleoanthropology. And yes, while we're at it, lets admit that I sometimes happen to share this belief. In its most easily parodied form it is the smug and unusable commandments of Derrick Jensen and Daniel Quinn (Oh no she didn't!) but in its less egocentric manifestations it appears as "Paleo" diets and fitness practices, Kim Stanley Robinson's weird "basic hominid behaviors" in Fifty Degrees Below, and several cultural writers too serious and considered to risk offending here. My personal take on the genre- that people are happier if they regularly eat and sing together, run around outdoors, eat vegetables, and live in groups, etc- would pass muster in any Transition Town Meeting and I don't aim to be mocked just because some of the foundation for my beliefs is, maybe, a little mockable.

The Raven's Gift, on the other hand, runs screamingly away from anthropology into outright mythmaking. The book makes a good subject for this essay because the author is so eminently un-self-aware that all the gears and pushrods of his thinking show through. And Jon Turk believes in the authenticity of the primitive and the falsity of the real.

In Turk's vision, the post-lapsarian west is obsessed with money, deceit, and hilarious non-sequiturs. He muses that the term "terra firma" is inappropriate for "Polar hunters... mountaineers or skiers... or river runners" all of whom are granted visions of changes in the Earth. Instead he suspects it was created by a "wordsmith who lived in downtown Rome, drank water out of lead pipes, and debauched at orgies, eating peeled grapes and roasted hummingbirds' tongues. Maybe he was a real estate developer trying to sell condos in Pompeii, with a large picture window view of Mount Vesuvius." Funny stuff!

Jill Bolte Taylor

It is not enough that Romans (who are, in his mind, the doomed teaching example for the modern West) are culturally different from his treasured Koryaks and kayakers. He proposes a physiological difference as well. Leaning heavily on the work of neurologist Jill Bolte Taylor and (the now-late) Leonard Shlain's The Alphabet vs.The Goddess, Turk believes that information about the natural world passes directly into the brain's right hemisphere, while symbolic communication (language etc) is processed on the left, and hence "a Koryak reindeer herder relies heavily on right-brain intuition" giving him senses that are inaccessible to left-dominant Americans and presumably Romans as well. This sense of anatomic deformity and loss plagues the book, as every failure, every doubt, every last minute run to the airport is bewailed as a consequence of his (Turk's) childhood loss, at age six, of his right brain hemisphere. He describes the scene dramatically:

I started first grade [at] a new brick and concrete block structure, cheerily named Park Avenue School. On moving day, we all lined up, shortest to tallest, boarded the yellow school bus, lined up again, and marched toward the building without talking or fidgeting. When I crossed the portal, I stared down a long, parallel hallway built of symmetrical monotonous rows of block, punctuated by steel doors that opened onto identical classrooms. Suddenly terrified, I stepped out of line, sat on the tile floor, and burst into tears.

I could never have formulated the angst in words I use now, but I must have intuitively recognized that at that moment I was being wrested from the right-brain world of my childhood- and my hominid ancestors. If I followed the path society was outlining for me, those halcyon days in the forest would be forever reserved for weekends and summer vacation- if I were lucky. The rest of the time I would sit at a desk, mind my manners, learn to add columns of numbers and do long division, and memorize fifty state capitals- all so I could perform efficiently in a left-brain society where I would operate computers and fill out tax forms.

Later, while scattering his wife's ashes in the wilderness, he comes across a Brown Bear and asks the reader what explanation they would choose for its presence: "A left-brained world of logic, wrapped in a statistical analysis of the probability of running into a grizzly bear on any given day? Or a right-brained world where magic flies around all the time, waiting to be plucked out of the sky?"

The idea that even the the decadent wordsmith of the first example would see a bear and think "statistics" is silly. Bears are amazing, and their reasons are their own. There is a very low probability that if I walk down to the kitchen I will not see a bear, and a much higher chance of seeing one if I hang out in the mountains of Colorado, but that has nothing to say about whether I believe in magic or whether I might try to show respect to a bear in a manner that has not been shown by experiment to mean a goddamn thing to bears. To Turk, "left-brain society" is a world deprived of wonderment, while he, his friends, his editors, and of course the people who buy his books (and keep the sea kayak manufacturers in business) are all universally exceptions to the rule. Is this really true? Or just Authentic? Turk's description of America seems as unreal as his anthropologically dubious Siberians.

Is it unavoiable that to believe in an Authentic world requires the blindered condemnation of the bulk of society? Turk is, after all, not being fair; America is not a culture of statisticians and cinderblock. Everybody has two hemispheres to their brain, both physically and metaphorically. Every life has moments of unpredictability and improvisation, every life has moments of repetition. No-one, after all, is Authentic, but discarding the romantic apposition of Authentic and Real also means that nobody exists in a state of fallen desolation. There are a lot of hunters, skiiers, kayakers, and bear-watchers out there, as well as people who refuse to go to law school because they'd rather spend time with their kids and gardens, or maybe they just call in laid to work.

There is, in Turk's book, the whiff of an apologia pro vita sua. He is tormented by the sight of his wife, perishing within view in a series of avalanches. He questions his decisions to forego a career as a chemist in favor of editing textbooks and adventuring. He worries about his constant tendency to abandon difficult situations for the comfort of a flight home and a second attempt next season. Casting these and other personal shortcomings as post-lapsarian compromises of the real, to be overcome in an authentic world by authentic reindeer herders in an authentic wilderness, both excuses and implicates him at the same time. He has, in effect, simplified his own moral narrative to the terms required by a romantic culture. And, we should thank him, because he has done so in a painfully obvious fashion that allows the rest of us to learn from him. But Turk has inadvertently presented "rewilding" bloggers with a challenge- how, other than a romantic moral narrative, can we proceed? And most importantly, how can we do so without condemning the rest of the world to a state of inauthenticity?

I can't in the end, dislike Jon Turk. He seems to be essentially decent, if driven by demons and embarassingly unaware of his good fortunes when they come. If he has embellished or mis-told a tale here, he has some answering to do to the Koryaks, and if he has written a clumsy, sometimes silly book, it cost me nothing to check it out from the library.

Best,

A

PS- It would have been SO EASY to work Sarah Palin into this post. I didn't. Thank me.

PPS- So, tell me who else on your blog roll researches the earliest helicopter out of which a shaman may be thrown? The testing took, like, all day at Burning Man...

While looking for a book on kayaking, I came across Jon Turk's The Raven's Gift: A Scientist, a Shaman, and Their Remarkable Journey Through the Siberian Wilderness. The subtitle mentions a "shaman" which is a +1 Word of Cheesiness and sure enough, the book is disappointing. Like most things on this blog, though, it also connects nicely to a larger question that's been turning over in my head for a while, and provides a bit of insight even as I choke over the hokier parts.

Jon Turk, the author, came to prominence with his earlier book, an arctic kayak travelogue titled In the Wake of the Jomon:Stone Age Mariners and a Voyage Across the Pacific. In it, Turk took inspiration from a spurious identification of the 9,500-yearold Kennewick Man found in Washington State as ethnically related to the Jomon, a prehistoric Japanese culture, and set out to prove that early Americans would not have had to rely on the (intermittently submerged) Bering Land Bridge to cross back and forth from Asia. Without getting too deep into the Clovis-first debate, indigenous scholars have been arguing for years that paleoindians were sophisticated enough to island-hop, while European archaeologists have claimed that the migration happened only once or only rarely, and depended on a very lucky series of coincidences to make it to what is now the mainland US.

Turk's 2000 voyage had the potential to be a Kon-Tiki-like proof of concept, but a number of workarounds undercut the validity of his effort, and critical archaeologists have little difficulty ignoring him. DNA analysis was never completed on the Kennewick remains, and the book, while available on google books, is not the one I'm reviewing today.

Raven's Gift opens midway through the first story. Turk and his Russian pal Misha have landed their kayaks on the Kamchatka peninsula in a storm, and are welcomed by a group of Koryaks who give them food, a place to stay, and a quick tour of the town of Vyvenka. Turk makes the brief acquaintance of an old woman he names Moolynaut who is a shaman and invites him back. Over the next few years he returns several times, undertaking or attempting quests for Moolynaut including locating "free living" reindeer herders not forced into cities by Soviet deracination, skiing to the Chukchi peninsula, and of course, taking lots of mushrooms. Throughout, he chases Kutcha the Koryak raven figure, and bewails his childhood imprisonment in a world of left-brain thinking. Eventually his wife dies.

The problem is that I don't believe him. I don't think he's faking, but he may be embellishing a lot. He mentions financial troubles after Jomon crashed and burned, one can imagine this book as a way out of a publishing contract, or debt- what editor, after all, will fact-check with a group of harried indigenous Russians living in Siberia? But I can fact-check on the internet, and the comparison doesn't flatter him. For instance, the Koryak raven spirit isn't Kutcha, its Quikil or Quikinnaqu. You could conceivably mistake the one for the other, and Turk is a lousy linguist whose transliteration of "visdichot" (for Russian:vezdekhod) was so impermeable I had to find a native speaker. Still, there are other problems.

In one scene, Turk describes picking a "wild cranberry" off the tundra and eating, savoring the sweetness. Does he mean a cloudberry? Or are wild cranberries in Siberia that different from every wild cranberry I've every eaten? Similarly, he both identifies and describes his "mukhomor" as Amanita muscaria (indeed, krasniy mukhomor is the Russian name, though the Koryak word is wapaq) but somehow fails to mention any of the well-known side effects when describing his mushroom trips. His characterizations of the Koryaks he meets are entertaining and well-realized, but once he drops past personal history into describing Koryak legends, belief, or history, he falls flat. The account of the Soviet collectivization campaign is repetitive and weirdly non-specific: he cites an apocryphal story about "Russians throwing shamans out of helicopters to see if they could fly," which the Soviets may well have done somewhere, but probably not during the 1931 creation of the Koryak SSR, since the first helicopter from which a shaman could have been thrown wasn't built until 1941.

I compare Turk unfavorably to Canadian Farley Mowat, whose Ihalmiut sequence (People of the Deer, The Desperate People, No Man's River and the cataclysmic sixty-year update Walking On the Land) still sets the standard for out-of-place-honky-writes-about-colonialism books. Although he is the "scientist" of the title, Turk's career as a research chemist ended in the sixties and he might more properly be termed a "writer of scientific textbooks and amateur adventurer." This book is clearly located in the adventure memoir genre, and despite his claim to being a "travelling storyteller" Jon Turk is dreadful at telling stories. He never gets inside the heads of his characters, never anticipates the reader's questions, and seems almost baby-like in his indifference to his own motivations in leading a life of Extreme Sports Adventure. Turk is like a bad date, who not only always talks about himself, he doesn't even have anything insightful about himself to say.

Some Dubious Romantic "Other" Books

It is enlightening to put Raven's Gift on the same shelf as Marlo Morgan's phony Mutant Message From Down Under, Isabel Fonseca's clueless Bury Me Standing or Eric Brende's dubious Better Off. Like them, a westerner seeks out an Outsider culture, incorporates into them for a period of time, and returns with a number of romantic insights on his or her own culture, all of which are easily challenged by both in- and out-culture scholars who have to spend a great deal of energy dissuading thrill seekers with boring tales of assimilation, stress, linguistic approximation, and, of course, the Roma words for all those concepts Fonseca claims the Roma don't have words for. Its worth noting that both Brende and Morgan specifically place their out-culture contacts in a "secret" location, where mainstream ethnographers never go- this is echoed in Turk's pilgrimage to find "untouched" reindeer herders. Its the new-age ethnography equivalent of What These People Need Is A Honky- its, What This Honky Needs Is A Pre-Contact People.

Now for the serious essay question: Why do these books keep getting written? What is it that draws American readers to doubtful yet utopian travelogues about pre-technological others? I think the reason (and so many other reasons as well) comes down to the romantic (and, in American culture, ubiquitous) conflict between the Authentic and the Real.

A few definitions first- the Real is more or less lived experience. I woke up today, put on cotton canvas trousers, walked the dogs, ate some oatmeal, sang a few stanzas of a Johnny Cash song to myself, called my work... etc. The details differ from day to day, person to person, but I imagine that most readers here had mornings that are, in terms of cultural valuations, the same. The Authentic is the idea of what a morning *should* be, if impediments were removed. Maybe mornings aren't such a good example- lets take Easter.

Real Easter goes like this: chocolate candies, and jellybeans, primarily egg- and rabbit-themed, show up in stores. People bag and basket them up for children. Decorations appear in non-strictly-secular environments that use lots of pastel colors and tulips. If you are Christian, you might go to church, quite possibly for the first time since Christmas. Kids get a week off school, though this may be a coincidence. (A more common history says spring break was time to help the family plant crops.)

Authentic Easter has a lot more to do with Jesus and crucifixion and redemption, a week of sorrow followed by a day of feasting. Authentic iconography involves capital punishment and graves. The difference drives Christians crazy. Some commentators, of course, will blame the media, and others will blame the schools. Most will place Authentic Easter in a semi-historical past that has been "lost" in the "modern age."

You can play this game with almost any holiday, but the pattern extends beyond the "secularization" of the calendar. Recently, Salon ran an article about "Hipsters on Food Stamps"- kids with educations and previously prestigious work histories, losing their jobs and claiming public benefits. What put online commentators in high dudgeon (oh who are we kidding, they live there- what they CLAIMED they were upset about) was that the hipsters were buying high-status foods like organic vegetables with their food stamps, instead of commodity cheese and cheerios. Nobody seemed to be able to articulate why an out-of-work graphic designer with two kids should be less deserving than an out-of-work steamfitter with two kids, nor was anyone arguing that poor people should be forced to eat unhealthy food. Still, it pissed people off like nothing you've ever seen.

The problem, of course, is that while the real category of poor people includes hipsters, the Authentic poor do not. Authentic poor Americans look like Florence Owens Thompson as photographed by Dorothea Lange in 1936:

Real poor Americans look like Florence Owens Thompson as photographed by her family in 1979:

Authenticity, in other words, is the cultural narrative we tell about how things should be. Very rarely does this coincide with how things are. The hipsters in the story, while real, were inauthentic, and therefore should not have been poor, or been treated as equal to authentic poor benefits recipients. Inauthenticity is the site of a great deal of cultural control in a variety of realms- consider then-governor Jesse Ventura's snarled 1999 promise to recognize tribal fishing rights only if Indians fished "in birch bark canoes." Despite being ridiculous on face, appearing authentic can be an obligation for out-groups in American culture, and its absence is used as a pretext for further disenfranchisement.

Nonetheless, Authenticity is percieved, at least in the Western imagination, to be lurking around the corner, in the next neighborhood, in the recent past, in the pre-contact indigenous- always just out of reach, but close enough to strive for. Dreams of authenticity are often displaced onto the poor or "working class." The Republican Authentic world, with its small towns, stable jobs, long-term monogamy, ethnic homogeneity and universal christianity, is perceived by Republicans to inhere in the Joe Plumbers of America, even if they (the Republicans, or for that matter any Joe Plumbers who make it onto TV) can't embody its ideals themselves. The Democratic Authentic world, with its convivial cosmopolitanism, fair deals for workers and neighbors, and chicken gardens, is similarly the province of Joe Union, even if this doesn't line up with reality either. Reality, for both parties, has a lot more suburbs and divorce, cheap beer, scandals, and ennui. But these are post-lapsarian, conditions of the fall. Vote for me, say the candidates, and we will return to the way things ought to be.

The debate between Reality and Authenticity has a strong parallel in the Eden legend- everything was great, then it got broken- and terms like "post-lapsarian" are entirely appropriate. However, its important to realize that the debate itself is a cultural narrative- one could, after all, recognize the suburban/divorce model of culture as the actual way American Humans live, without ever positing some other way that has been lost- and that as a narrative both sides are supremely contemporary, and also inherently reactionary. Inherently reactionary because if you argue too strongly for the Real, and you end up stagnant, recreating the same damn cut-out paper bunnies every year, but if you argue too strongly for the Authentic and you end up expelling the interlopers from your homelands.

Supremely contemporary because stories about the life we're being kept from- by secularism, by the spectacle, by decadence, by technology, by too much left-brained thinking- are just that: stories. Not just stories, but modern stories, rewritten every generation. The Authentic world is every bit as much of-the-moment as the cell phones and block scheduling we perceive as impediments to reaching it. By looking at our quasi-historical, or quasi-geographic vision of "how things used to/ought to be," what we in fact see is something about how things really are in our hearts. Which is what brings us back to Mr. Turk and his book (did you remember this was a book report?) and another subject dear to my heart- apocalyptic neoprimitivism.

(That's Jon Turk, by the way- I can't bring myself to dislike him)

There is a strain of thought, lets call it "rewilding," that believes the path to Authenticity is through anthropology, specifically paleoanthropology. And yes, while we're at it, lets admit that I sometimes happen to share this belief. In its most easily parodied form it is the smug and unusable commandments of Derrick Jensen and Daniel Quinn (Oh no she didn't!) but in its less egocentric manifestations it appears as "Paleo" diets and fitness practices, Kim Stanley Robinson's weird "basic hominid behaviors" in Fifty Degrees Below, and several cultural writers too serious and considered to risk offending here. My personal take on the genre- that people are happier if they regularly eat and sing together, run around outdoors, eat vegetables, and live in groups, etc- would pass muster in any Transition Town Meeting and I don't aim to be mocked just because some of the foundation for my beliefs is, maybe, a little mockable.

The Raven's Gift, on the other hand, runs screamingly away from anthropology into outright mythmaking. The book makes a good subject for this essay because the author is so eminently un-self-aware that all the gears and pushrods of his thinking show through. And Jon Turk believes in the authenticity of the primitive and the falsity of the real.

In Turk's vision, the post-lapsarian west is obsessed with money, deceit, and hilarious non-sequiturs. He muses that the term "terra firma" is inappropriate for "Polar hunters... mountaineers or skiers... or river runners" all of whom are granted visions of changes in the Earth. Instead he suspects it was created by a "wordsmith who lived in downtown Rome, drank water out of lead pipes, and debauched at orgies, eating peeled grapes and roasted hummingbirds' tongues. Maybe he was a real estate developer trying to sell condos in Pompeii, with a large picture window view of Mount Vesuvius." Funny stuff!

Jill Bolte Taylor

It is not enough that Romans (who are, in his mind, the doomed teaching example for the modern West) are culturally different from his treasured Koryaks and kayakers. He proposes a physiological difference as well. Leaning heavily on the work of neurologist Jill Bolte Taylor and (the now-late) Leonard Shlain's The Alphabet vs.The Goddess, Turk believes that information about the natural world passes directly into the brain's right hemisphere, while symbolic communication (language etc) is processed on the left, and hence "a Koryak reindeer herder relies heavily on right-brain intuition" giving him senses that are inaccessible to left-dominant Americans and presumably Romans as well. This sense of anatomic deformity and loss plagues the book, as every failure, every doubt, every last minute run to the airport is bewailed as a consequence of his (Turk's) childhood loss, at age six, of his right brain hemisphere. He describes the scene dramatically:

I started first grade [at] a new brick and concrete block structure, cheerily named Park Avenue School. On moving day, we all lined up, shortest to tallest, boarded the yellow school bus, lined up again, and marched toward the building without talking or fidgeting. When I crossed the portal, I stared down a long, parallel hallway built of symmetrical monotonous rows of block, punctuated by steel doors that opened onto identical classrooms. Suddenly terrified, I stepped out of line, sat on the tile floor, and burst into tears.

I could never have formulated the angst in words I use now, but I must have intuitively recognized that at that moment I was being wrested from the right-brain world of my childhood- and my hominid ancestors. If I followed the path society was outlining for me, those halcyon days in the forest would be forever reserved for weekends and summer vacation- if I were lucky. The rest of the time I would sit at a desk, mind my manners, learn to add columns of numbers and do long division, and memorize fifty state capitals- all so I could perform efficiently in a left-brain society where I would operate computers and fill out tax forms.

Later, while scattering his wife's ashes in the wilderness, he comes across a Brown Bear and asks the reader what explanation they would choose for its presence: "A left-brained world of logic, wrapped in a statistical analysis of the probability of running into a grizzly bear on any given day? Or a right-brained world where magic flies around all the time, waiting to be plucked out of the sky?"

The idea that even the the decadent wordsmith of the first example would see a bear and think "statistics" is silly. Bears are amazing, and their reasons are their own. There is a very low probability that if I walk down to the kitchen I will not see a bear, and a much higher chance of seeing one if I hang out in the mountains of Colorado, but that has nothing to say about whether I believe in magic or whether I might try to show respect to a bear in a manner that has not been shown by experiment to mean a goddamn thing to bears. To Turk, "left-brain society" is a world deprived of wonderment, while he, his friends, his editors, and of course the people who buy his books (and keep the sea kayak manufacturers in business) are all universally exceptions to the rule. Is this really true? Or just Authentic? Turk's description of America seems as unreal as his anthropologically dubious Siberians.

Is it unavoiable that to believe in an Authentic world requires the blindered condemnation of the bulk of society? Turk is, after all, not being fair; America is not a culture of statisticians and cinderblock. Everybody has two hemispheres to their brain, both physically and metaphorically. Every life has moments of unpredictability and improvisation, every life has moments of repetition. No-one, after all, is Authentic, but discarding the romantic apposition of Authentic and Real also means that nobody exists in a state of fallen desolation. There are a lot of hunters, skiiers, kayakers, and bear-watchers out there, as well as people who refuse to go to law school because they'd rather spend time with their kids and gardens, or maybe they just call in laid to work.

There is, in Turk's book, the whiff of an apologia pro vita sua. He is tormented by the sight of his wife, perishing within view in a series of avalanches. He questions his decisions to forego a career as a chemist in favor of editing textbooks and adventuring. He worries about his constant tendency to abandon difficult situations for the comfort of a flight home and a second attempt next season. Casting these and other personal shortcomings as post-lapsarian compromises of the real, to be overcome in an authentic world by authentic reindeer herders in an authentic wilderness, both excuses and implicates him at the same time. He has, in effect, simplified his own moral narrative to the terms required by a romantic culture. And, we should thank him, because he has done so in a painfully obvious fashion that allows the rest of us to learn from him. But Turk has inadvertently presented "rewilding" bloggers with a challenge- how, other than a romantic moral narrative, can we proceed? And most importantly, how can we do so without condemning the rest of the world to a state of inauthenticity?

I can't in the end, dislike Jon Turk. He seems to be essentially decent, if driven by demons and embarassingly unaware of his good fortunes when they come. If he has embellished or mis-told a tale here, he has some answering to do to the Koryaks, and if he has written a clumsy, sometimes silly book, it cost me nothing to check it out from the library.

Best,

A

PS- It would have been SO EASY to work Sarah Palin into this post. I didn't. Thank me.

PPS- So, tell me who else on your blog roll researches the earliest helicopter out of which a shaman may be thrown? The testing took, like, all day at Burning Man...