Article with Anita Thompson

I read this article that was on the front cover of a newspaper called The Review with Hunter S. Thompson's widow. It's really really interesting to hear about him from her point of view.

A Lonely Legacy

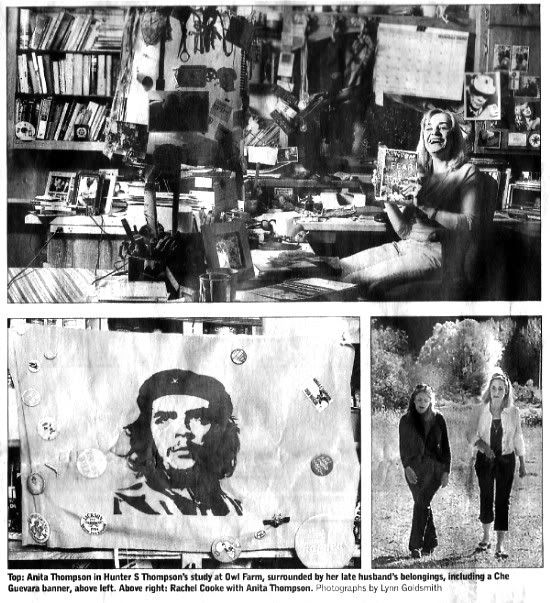

by Rachel Cooke

Owl Farm, which lies in Woody Creek, Pitkin County, Colorado, is an unassuming kind of building, one without airs or graces or even, sad to say, a power shower or new refrigerator. But it is also legendary, in its way. It was in this ran shackle wooden house that Hunter S. Thompson, the hard-drinking, hard-writing, drug-loving, gun-loving gonzo journalist lived for more than three decades. And it was here, too, that last February, at the age of 67, he shot and killed himself with a .45 calibre pistol. For a certain kind of person, this was - and still is - a place of pilgrimage. This was where you came if you despised bourgeois self-satisfaction, and shabbiness, and hypocrisy; this, too, was where you came if you loathed President Bush (though those who hated President Clinton where, conversely, every bit as welcome).

It was the high alter of freedom and bravery, of good jokes and living on the edge; it was, if you like, a temple to contrariness. And if you just happened to enjoy dope and cocaine and speed, and were prepared to wash them all down with a long glass of Chivas Regal, well, so much the better. A murderous hangover was as nothing to a true Owl Farm groupie.

Naturally, most of these groupies were - are - men. Thompson liked women, and had relationships with more than a few of them, but it was men he spoke to, appealing, I guess, to their insecure, macho sides. Or at least, this is what I find myself thinking on my way over there to meet Thompson's widow, Anita. God, how male is this world is. I've been picked up by a taxi driver who happens to keep a tired copy of Thompson's Fear and Loathing on the Campiagn Trail '72 on his dashboard. And this man, in blue jeans and check shirt, is now telling me that he has written a book - it's in iambic pentameter - about the fact that, for the last seven years, he has refused to pay taxes. On and on he goes, dogged and angry and full of testosterone.

I look out of the window. Four-wheel-drives flash by. The land, once you leave behind Aspen, with its Dior boutique and its 'upscale dining experiences', is rocky and lonely - straight out of a Marlboro ad to British eyes. It is very beautiful, but it makes me shiver. In the winter, when the snow lies heavy on the ground, a girl might feel like she had been buried alive out here.

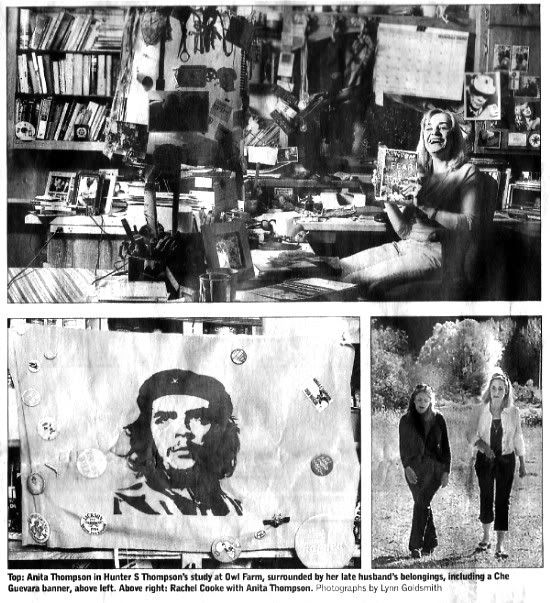

In a way, of course, this is precisely what has happened to Anita Thompson. Although Hunter is gone, she is still surrounded by him, weighed down not only by his papers, which entirely fill the basement, but also by his stuff, which covers every surface, and which she will never be able to throw away.

After I've got rid of the taxi driver, Anita takes me inside and makes me - unexpected, this - a cup of Lady Grey tea. Then, while she disappears to dry her hair, I have a look round. The experience is like being in some crazy, hippie version of Sale of the Century. In the living room, I see: a cactus, a stuffed alligator, a small cannon, an exercise bike, a ram's head, a stuffed crow, the Encylopaedia Britannica, an owl, a human skull and a blue candle in the shape of a woman with its wicks as nipples. In the kitchen, Hunter's handwritten notes - 'Let's get stoned and have orgasms and laugh a lot' - are stuck to every wall. So, too, are photographs of him. In one, he is wearing lipstick and a pink wig. It is captioned: 'Hunter's aunt visits, September 2004.' On a kitchen counter is a lamp. On its shade hang some 30 pairs of Hunter's spectacles, their glass still smeared with fingerprints.

'I know,' she smiles, when she emerges and finds me gazing at these. 'I have an obligation to let go. My family says that. My mother says, "You don't want to live in a shrine." But it isn't a shrine. I did let go. I had to. I just don't... can't change things, that's all.' His possessions help her to feel his spirit, she says, though it would be tangible to her, even without them. 'His spirit is here. It's very strong, and I'm still married to that spirit.' She places her hand on her chest, as if feeling for a heartbeat. 'I don't know if you can sense it, but I know it's here, and I'm so grateful for that. We're lucky in a way. We have a thousand hours of his voice recorded. I have a hundred interviews I did with him. He was obsessed with recording everything, thank God. Then there are his books. If you read his work now, it has a new sparkle. Perhaps because now we only have a finite amount of words. Imagine if, in some twisted world, he'd have taken his words with him; if we picked up his books, and there were only empty pages; if every box in the basement held only blank manuscripts. So, obviously he's still with us.' She takes a deep breath. 'Yes, we are luckier than some.'

Anita Thompson was at the gym when she heard that something had happened to Hunter. It was Juan, his grown-up son from his first marriage, who called her. 'I didn't believe it. I thought Hunter had fallen down and that poor Juan had panicked and called 911. I thought everything would be fine until I called the sheriff.' By the time she got home, the house was full of people, and Hunter was sitting in his chair by the stove - the same spot in which she is sitting now, and where you can still see a bullet hole in the oven hood - looking 'beautiful', but very definitely dead.

Did she feel angry that he had done this? And with his son and small grandson in the next room? 'I felt guilty. I have more regrets than you could possibly imagine. I wish that I'd been here, that I hadn't gone out, that I'd paid attention to the signs. There'd been signs since he was 22, but now there were new signs. I knew something was wrong, but I didn't know what it was, and that was my job as a wife. He was mean, but between these snappy spells, he was more affectionate, more loving, than he had ever been.

'A month before [he died] he faxed a letter to my mum's house. I was staying there because things were so bad. "I love you so much, " it said. "I love you enough to set you free." I thought: maybe he's getting sick of me, like so many of the other women. But when I asked him what he meant by that, he wouldn't address it. He would just hold me. Looking back, why was I so insecure? Why didn't I get that? Maybe it's too soon for me to give advice to other women who've lost their husbands, but what I would say is: say how much you love eachother all the time. When we married, we both acknowledged that he was going to die before me, but I thought that we would have at least ten years. We were trying to have a kid.' Not that she is making out that her husband was a saint; the last months - when Thompson was in pain, and often in a wheelchair, following back surgery and a broken leg - were difficult. 'You bet I felt worn down by it,' she winces. 'It was hard. He was hard on people. It was hell.'

It took her a while to accept that he was not coming back. 'I dressed his body, so I knew he was dead. But I didn't grasp it.' She was too busy to acknowledge her loss. First, there was the funeral. Then, six months later, there was the memorial service, in which Hunter's ashes - as he had stipulated in his will - were fired far across Owl Farm's acres in a rocket. 'It was like preparing for a wedding, so I was distracted,' she says. 'I didn't want Hunter's ashes to leave the farm at first. I wasn't going to let them out of my sight. So I had to fly with them to the firework factory, which was in Pennsylvania. I went to the bunker, and they had the canisters for the rockets there, open, so they could be sealed with me there. They put the ashes in and I wrote on each seal, "I love you, Hunter." It was a kind of blessing, but it was also so I knew that the ashes were coming back.'

Thirty-two rockets were fired in the end, form a 'supergun' topped by the double-thumbed red fist that symbolises 'gonzo'. In attendance were Sean Penn, Bill Murray, Johnny Depp, John Kerry and George McGovern. 'It was beautiful. It was what he wanted. There was a sense of peace after the ashes settled. Then we got drunk. Yes, I would say it was an all-nighter.'

But between both thsese events, she found herself staring into the abyss. 'After five months, that was when it hit me. Until then, I still had this feeling that he'd come into the room, or that we'd get a call and find out that it had been a joke. I thought, this is all so out of my league. The responsibility was overwhelming. I thought I would fail him, make a mess of things. I was suicidal.

Two men helped her get through. One was Ralph Steadman, Hunter's friend and long-time collaborator, who sent her encouraging faxes every morning. The other - and who knows what Hunter would have made of this? - was Deepak Chopra, to whose San Diego centre she went to recuperate.

'When I came back, I was stronger. But what really saved me was writing to Hunter. I still do that every day. That helps a lot. I keep up a connection with him. It's like a portal to him in my own mind.' Has he left her well provided for? 'He's the best husband you can possibly imagine. I'm secure in terms of having a home, and I'll be working for Hunter for the rest of my life [she is helping to edit a third volume of his letters, though at present reading them is still too painful]. But not in terms of money. There isn't much money, though people think there is. But I've always known that because I worked for Hunter.'

Anita grew up in Fort Collins, Colorado, the daughter of Polish immigrants. Her mother is a property developer; her father now runs a business in Kiev. They were quite protective of her, growing up - when they thought she was becoming 'too American', she was swiftly dispatched to school in Switzerland - so you can imagine how they must have felt when Hunter S. Thompson stumbled into her life. 'My mum disowned me for a while. There was a huge uproar in the family. There was an age difference of 35 years, so he was older than my mum and dad. I didn't understand the problem with the age difference. Hunter was the most fun of any man I'd ever been with. I was the adult, and that didn't bother me at all. But it bothered them. My mum had heard stories about his drug use. She made me choose, basically. It was an easy choice for me; painful, but easy.'

He won her mother over in the end. 'We thought they should meet on neutral ground. We were at a book-signing in New York. We got back to the Carlyle late at night. She was asleep, but he said, "Wake her up, bring her over now." So she came in her robe. Hunter always used to greet people in his robe, but on this occasion, he was in a suit. He ordered champagne and caviar and charmed the pants off her like any southern gentleman [Hunter was from Kentucky]. She totally fell in love with him.'

Anita had been on a break from university when she first met Hunter, working as a nanny and in a ski shop on Aspen mountain. She was just 25. 'I learned to snowboard, and I didn't want to leave. Then I had an interesting learning about football, and a friend of mine said, "I know just the person. He's a writer." I hadn't read him, only part of a piece he wrote in Rolling Stone on Bill Clinton. That was eight years ago. I haven't known Hunter that long; I'm the newcomer for sure. But actually, he liked that about me. I was new, and he liked to teach me all the time.'

She started working for him, doing the photocopying, and the odd bit of research. 'I fell in love with him right away. I think he was used to that - his assistants falling in love with him. I would start at eight at night [Thompson's hours were legendary; he rarely rose before teatime] and leave around midnight. I spent hours and hours reading. It was becoming obvious [what was happening]. I moved in here in January 2000.

'We married in April 2003. At first, I didn't want to get married. It was working very well living together. We were getting a lot of work done. He wrote more in the last five years of his life than he had done in the previous 15. We worked well together, and there were a couple of people in our circle who were not happy about it; I didn't want to upset them. Hunter said it was pure jealousy. It was a territorial thing, and I worried about it because the dynamics around here were so delicate. But then he wrote me the most beautiful love letter, and so I said, "Of course, any time you want." In his heart, he was old-fashioned. The way he put it was that it was predetermined before me met. But he was also afraid that if something happened to him during back surgery, they would - quotes- "eat you alive". We went to the courthouse at eight o' clock in the morning, where the sheriff and his wife were our best friends. We signed the papers, paid $5 each, and that was it. When we came home, put our robes on and watched the basketball.

So how was married life? 'There was a dark side to Hunter. He was a lord of the underworld, which can be exciting and creative, but also hard to be around. He could be cruel, and not just to me. He was always honest; that could be painful.'

Didn't she ever get sick of the groupies? 'Sometimes, but Hunter took care of that. He always knew the bad apples in a room. He has this way of looking at someone, and seeing their motivation.' But the place ran on cocaine and booze, and that was more difficult to deal with. 'I worried about him, but I never told him to stop. That was an agreement we made.'

Did she join in? 'I was curious, so I tried it all. I ended up with a serious drug problem. But after about two years, I realised, I can't keep up with this guy. There were so many drunk people around, I thought, someone's got to stay sober. It was hard to get off it because of the environment, but it was either that or I had to leave. He didn't like to lose a party buddy, but he was supportive. My rehab was in a drugs den! His motto was: it's wrong when it stops being fun. It wasn't fun for me; it was horrible. But it was fun for him right up until the very end.'

It is impossible not to like Anita Thompson - there is something so sweet-natured about her, so open and unexpectedly straightforward - but it is hard, too, not to worry about her. My sense is that she is very alone in Woody Creek, for all that people drop by and the phone rings often. She keeps the lights on in the guest house even when it is empty, and has had a new security system installed in the main building. But it is quiet as the grave here which, given her situation, cannot be very helpful.

After we have finished talking, she takes me to walk across Hunter's land and what she jokingly calls her office, but which is really only a patch of scrubby land in a thicket by the brackish-looking stream (though the view of the mountains is Technicolor perfect). She has dragged two dirty sun chairs and an ancient table up here (The spare chair is for her new Alsatian, Athena, whose bark is comfortingly loud). Beneath the table, in zip-lock plastic bags, are two books by Hunter and some hash.

'I had some other things too, but a bear tried to eat them,' she says. 'I like to think that was Hunter.' She laughs, which is something she does a lot, though you feel she is only a hair's breadth from tears most of the time. 'I spent the summer up here, writing to Hunter, reading his books.' She picks one up - it is The Great Shark Hunt - and begins reading in a loud voice that is both faltering and determined.

What will become of her? 'Oh, it's easy to be loyal,' she says. 'That's my choice. I don't have any intention of getting remarried. I'm 33, so statistically, I'm going to live for another 39 or 40 years. But no other man will be able to hold a candle to Hunter. I guess I'm in a bad position in one way. But I'm not hypnotised. I'm not in a trance. I made a conscious decision to dedicate at least the next few decades to him when we got married.'

One day, she would like Owl Farm to become a writer's centre, but in the meantime, she intends to stay put. 'It used to be much harder. I would buy radishes at the grocery store, even though I wasn't going to eat them myself. Or I would make a cooked breakfast, the same way I used to for Hunter, even though I wasn't hungry. Sleeping is still not easy; the bed is empty. But in other ways, it's getting better. I might pause and think about him, but there's not that pain coming in the way there used to be. I don't forget he's gone as often as I used to.'

Even so, she must fear the icy grasp of winter, which cannot be far off now. 'Oh, yes. The winter used to be fun. We'd lay a fire, and hunker down together in our robes. But this year, it really will be cold.'

A website, drhuntersthompson.com, will be up and running in January 2006. Anita Thompson is currently working on A Book of Hunter's Wisdom, and helping to edit Hunter's book, Polo is My Life.

A Lonely Legacy

by Rachel Cooke

Owl Farm, which lies in Woody Creek, Pitkin County, Colorado, is an unassuming kind of building, one without airs or graces or even, sad to say, a power shower or new refrigerator. But it is also legendary, in its way. It was in this ran shackle wooden house that Hunter S. Thompson, the hard-drinking, hard-writing, drug-loving, gun-loving gonzo journalist lived for more than three decades. And it was here, too, that last February, at the age of 67, he shot and killed himself with a .45 calibre pistol. For a certain kind of person, this was - and still is - a place of pilgrimage. This was where you came if you despised bourgeois self-satisfaction, and shabbiness, and hypocrisy; this, too, was where you came if you loathed President Bush (though those who hated President Clinton where, conversely, every bit as welcome).

It was the high alter of freedom and bravery, of good jokes and living on the edge; it was, if you like, a temple to contrariness. And if you just happened to enjoy dope and cocaine and speed, and were prepared to wash them all down with a long glass of Chivas Regal, well, so much the better. A murderous hangover was as nothing to a true Owl Farm groupie.

Naturally, most of these groupies were - are - men. Thompson liked women, and had relationships with more than a few of them, but it was men he spoke to, appealing, I guess, to their insecure, macho sides. Or at least, this is what I find myself thinking on my way over there to meet Thompson's widow, Anita. God, how male is this world is. I've been picked up by a taxi driver who happens to keep a tired copy of Thompson's Fear and Loathing on the Campiagn Trail '72 on his dashboard. And this man, in blue jeans and check shirt, is now telling me that he has written a book - it's in iambic pentameter - about the fact that, for the last seven years, he has refused to pay taxes. On and on he goes, dogged and angry and full of testosterone.

I look out of the window. Four-wheel-drives flash by. The land, once you leave behind Aspen, with its Dior boutique and its 'upscale dining experiences', is rocky and lonely - straight out of a Marlboro ad to British eyes. It is very beautiful, but it makes me shiver. In the winter, when the snow lies heavy on the ground, a girl might feel like she had been buried alive out here.

In a way, of course, this is precisely what has happened to Anita Thompson. Although Hunter is gone, she is still surrounded by him, weighed down not only by his papers, which entirely fill the basement, but also by his stuff, which covers every surface, and which she will never be able to throw away.

After I've got rid of the taxi driver, Anita takes me inside and makes me - unexpected, this - a cup of Lady Grey tea. Then, while she disappears to dry her hair, I have a look round. The experience is like being in some crazy, hippie version of Sale of the Century. In the living room, I see: a cactus, a stuffed alligator, a small cannon, an exercise bike, a ram's head, a stuffed crow, the Encylopaedia Britannica, an owl, a human skull and a blue candle in the shape of a woman with its wicks as nipples. In the kitchen, Hunter's handwritten notes - 'Let's get stoned and have orgasms and laugh a lot' - are stuck to every wall. So, too, are photographs of him. In one, he is wearing lipstick and a pink wig. It is captioned: 'Hunter's aunt visits, September 2004.' On a kitchen counter is a lamp. On its shade hang some 30 pairs of Hunter's spectacles, their glass still smeared with fingerprints.

'I know,' she smiles, when she emerges and finds me gazing at these. 'I have an obligation to let go. My family says that. My mother says, "You don't want to live in a shrine." But it isn't a shrine. I did let go. I had to. I just don't... can't change things, that's all.' His possessions help her to feel his spirit, she says, though it would be tangible to her, even without them. 'His spirit is here. It's very strong, and I'm still married to that spirit.' She places her hand on her chest, as if feeling for a heartbeat. 'I don't know if you can sense it, but I know it's here, and I'm so grateful for that. We're lucky in a way. We have a thousand hours of his voice recorded. I have a hundred interviews I did with him. He was obsessed with recording everything, thank God. Then there are his books. If you read his work now, it has a new sparkle. Perhaps because now we only have a finite amount of words. Imagine if, in some twisted world, he'd have taken his words with him; if we picked up his books, and there were only empty pages; if every box in the basement held only blank manuscripts. So, obviously he's still with us.' She takes a deep breath. 'Yes, we are luckier than some.'

Anita Thompson was at the gym when she heard that something had happened to Hunter. It was Juan, his grown-up son from his first marriage, who called her. 'I didn't believe it. I thought Hunter had fallen down and that poor Juan had panicked and called 911. I thought everything would be fine until I called the sheriff.' By the time she got home, the house was full of people, and Hunter was sitting in his chair by the stove - the same spot in which she is sitting now, and where you can still see a bullet hole in the oven hood - looking 'beautiful', but very definitely dead.

Did she feel angry that he had done this? And with his son and small grandson in the next room? 'I felt guilty. I have more regrets than you could possibly imagine. I wish that I'd been here, that I hadn't gone out, that I'd paid attention to the signs. There'd been signs since he was 22, but now there were new signs. I knew something was wrong, but I didn't know what it was, and that was my job as a wife. He was mean, but between these snappy spells, he was more affectionate, more loving, than he had ever been.

'A month before [he died] he faxed a letter to my mum's house. I was staying there because things were so bad. "I love you so much, " it said. "I love you enough to set you free." I thought: maybe he's getting sick of me, like so many of the other women. But when I asked him what he meant by that, he wouldn't address it. He would just hold me. Looking back, why was I so insecure? Why didn't I get that? Maybe it's too soon for me to give advice to other women who've lost their husbands, but what I would say is: say how much you love eachother all the time. When we married, we both acknowledged that he was going to die before me, but I thought that we would have at least ten years. We were trying to have a kid.' Not that she is making out that her husband was a saint; the last months - when Thompson was in pain, and often in a wheelchair, following back surgery and a broken leg - were difficult. 'You bet I felt worn down by it,' she winces. 'It was hard. He was hard on people. It was hell.'

It took her a while to accept that he was not coming back. 'I dressed his body, so I knew he was dead. But I didn't grasp it.' She was too busy to acknowledge her loss. First, there was the funeral. Then, six months later, there was the memorial service, in which Hunter's ashes - as he had stipulated in his will - were fired far across Owl Farm's acres in a rocket. 'It was like preparing for a wedding, so I was distracted,' she says. 'I didn't want Hunter's ashes to leave the farm at first. I wasn't going to let them out of my sight. So I had to fly with them to the firework factory, which was in Pennsylvania. I went to the bunker, and they had the canisters for the rockets there, open, so they could be sealed with me there. They put the ashes in and I wrote on each seal, "I love you, Hunter." It was a kind of blessing, but it was also so I knew that the ashes were coming back.'

Thirty-two rockets were fired in the end, form a 'supergun' topped by the double-thumbed red fist that symbolises 'gonzo'. In attendance were Sean Penn, Bill Murray, Johnny Depp, John Kerry and George McGovern. 'It was beautiful. It was what he wanted. There was a sense of peace after the ashes settled. Then we got drunk. Yes, I would say it was an all-nighter.'

But between both thsese events, she found herself staring into the abyss. 'After five months, that was when it hit me. Until then, I still had this feeling that he'd come into the room, or that we'd get a call and find out that it had been a joke. I thought, this is all so out of my league. The responsibility was overwhelming. I thought I would fail him, make a mess of things. I was suicidal.

Two men helped her get through. One was Ralph Steadman, Hunter's friend and long-time collaborator, who sent her encouraging faxes every morning. The other - and who knows what Hunter would have made of this? - was Deepak Chopra, to whose San Diego centre she went to recuperate.

'When I came back, I was stronger. But what really saved me was writing to Hunter. I still do that every day. That helps a lot. I keep up a connection with him. It's like a portal to him in my own mind.' Has he left her well provided for? 'He's the best husband you can possibly imagine. I'm secure in terms of having a home, and I'll be working for Hunter for the rest of my life [she is helping to edit a third volume of his letters, though at present reading them is still too painful]. But not in terms of money. There isn't much money, though people think there is. But I've always known that because I worked for Hunter.'

Anita grew up in Fort Collins, Colorado, the daughter of Polish immigrants. Her mother is a property developer; her father now runs a business in Kiev. They were quite protective of her, growing up - when they thought she was becoming 'too American', she was swiftly dispatched to school in Switzerland - so you can imagine how they must have felt when Hunter S. Thompson stumbled into her life. 'My mum disowned me for a while. There was a huge uproar in the family. There was an age difference of 35 years, so he was older than my mum and dad. I didn't understand the problem with the age difference. Hunter was the most fun of any man I'd ever been with. I was the adult, and that didn't bother me at all. But it bothered them. My mum had heard stories about his drug use. She made me choose, basically. It was an easy choice for me; painful, but easy.'

He won her mother over in the end. 'We thought they should meet on neutral ground. We were at a book-signing in New York. We got back to the Carlyle late at night. She was asleep, but he said, "Wake her up, bring her over now." So she came in her robe. Hunter always used to greet people in his robe, but on this occasion, he was in a suit. He ordered champagne and caviar and charmed the pants off her like any southern gentleman [Hunter was from Kentucky]. She totally fell in love with him.'

Anita had been on a break from university when she first met Hunter, working as a nanny and in a ski shop on Aspen mountain. She was just 25. 'I learned to snowboard, and I didn't want to leave. Then I had an interesting learning about football, and a friend of mine said, "I know just the person. He's a writer." I hadn't read him, only part of a piece he wrote in Rolling Stone on Bill Clinton. That was eight years ago. I haven't known Hunter that long; I'm the newcomer for sure. But actually, he liked that about me. I was new, and he liked to teach me all the time.'

She started working for him, doing the photocopying, and the odd bit of research. 'I fell in love with him right away. I think he was used to that - his assistants falling in love with him. I would start at eight at night [Thompson's hours were legendary; he rarely rose before teatime] and leave around midnight. I spent hours and hours reading. It was becoming obvious [what was happening]. I moved in here in January 2000.

'We married in April 2003. At first, I didn't want to get married. It was working very well living together. We were getting a lot of work done. He wrote more in the last five years of his life than he had done in the previous 15. We worked well together, and there were a couple of people in our circle who were not happy about it; I didn't want to upset them. Hunter said it was pure jealousy. It was a territorial thing, and I worried about it because the dynamics around here were so delicate. But then he wrote me the most beautiful love letter, and so I said, "Of course, any time you want." In his heart, he was old-fashioned. The way he put it was that it was predetermined before me met. But he was also afraid that if something happened to him during back surgery, they would - quotes- "eat you alive". We went to the courthouse at eight o' clock in the morning, where the sheriff and his wife were our best friends. We signed the papers, paid $5 each, and that was it. When we came home, put our robes on and watched the basketball.

So how was married life? 'There was a dark side to Hunter. He was a lord of the underworld, which can be exciting and creative, but also hard to be around. He could be cruel, and not just to me. He was always honest; that could be painful.'

Didn't she ever get sick of the groupies? 'Sometimes, but Hunter took care of that. He always knew the bad apples in a room. He has this way of looking at someone, and seeing their motivation.' But the place ran on cocaine and booze, and that was more difficult to deal with. 'I worried about him, but I never told him to stop. That was an agreement we made.'

Did she join in? 'I was curious, so I tried it all. I ended up with a serious drug problem. But after about two years, I realised, I can't keep up with this guy. There were so many drunk people around, I thought, someone's got to stay sober. It was hard to get off it because of the environment, but it was either that or I had to leave. He didn't like to lose a party buddy, but he was supportive. My rehab was in a drugs den! His motto was: it's wrong when it stops being fun. It wasn't fun for me; it was horrible. But it was fun for him right up until the very end.'

It is impossible not to like Anita Thompson - there is something so sweet-natured about her, so open and unexpectedly straightforward - but it is hard, too, not to worry about her. My sense is that she is very alone in Woody Creek, for all that people drop by and the phone rings often. She keeps the lights on in the guest house even when it is empty, and has had a new security system installed in the main building. But it is quiet as the grave here which, given her situation, cannot be very helpful.

After we have finished talking, she takes me to walk across Hunter's land and what she jokingly calls her office, but which is really only a patch of scrubby land in a thicket by the brackish-looking stream (though the view of the mountains is Technicolor perfect). She has dragged two dirty sun chairs and an ancient table up here (The spare chair is for her new Alsatian, Athena, whose bark is comfortingly loud). Beneath the table, in zip-lock plastic bags, are two books by Hunter and some hash.

'I had some other things too, but a bear tried to eat them,' she says. 'I like to think that was Hunter.' She laughs, which is something she does a lot, though you feel she is only a hair's breadth from tears most of the time. 'I spent the summer up here, writing to Hunter, reading his books.' She picks one up - it is The Great Shark Hunt - and begins reading in a loud voice that is both faltering and determined.

What will become of her? 'Oh, it's easy to be loyal,' she says. 'That's my choice. I don't have any intention of getting remarried. I'm 33, so statistically, I'm going to live for another 39 or 40 years. But no other man will be able to hold a candle to Hunter. I guess I'm in a bad position in one way. But I'm not hypnotised. I'm not in a trance. I made a conscious decision to dedicate at least the next few decades to him when we got married.'

One day, she would like Owl Farm to become a writer's centre, but in the meantime, she intends to stay put. 'It used to be much harder. I would buy radishes at the grocery store, even though I wasn't going to eat them myself. Or I would make a cooked breakfast, the same way I used to for Hunter, even though I wasn't hungry. Sleeping is still not easy; the bed is empty. But in other ways, it's getting better. I might pause and think about him, but there's not that pain coming in the way there used to be. I don't forget he's gone as often as I used to.'

Even so, she must fear the icy grasp of winter, which cannot be far off now. 'Oh, yes. The winter used to be fun. We'd lay a fire, and hunker down together in our robes. But this year, it really will be cold.'

A website, drhuntersthompson.com, will be up and running in January 2006. Anita Thompson is currently working on A Book of Hunter's Wisdom, and helping to edit Hunter's book, Polo is My Life.