Bipolar Sherlock: A More Detailed Analysis

Does Sherlock have a bipolar affective disorder?

In the last article I have many comments saying that I did not give enough information about Bipolar. So now I have completely rewritten the article.

Syndromes and Disease - A Step Back in Time

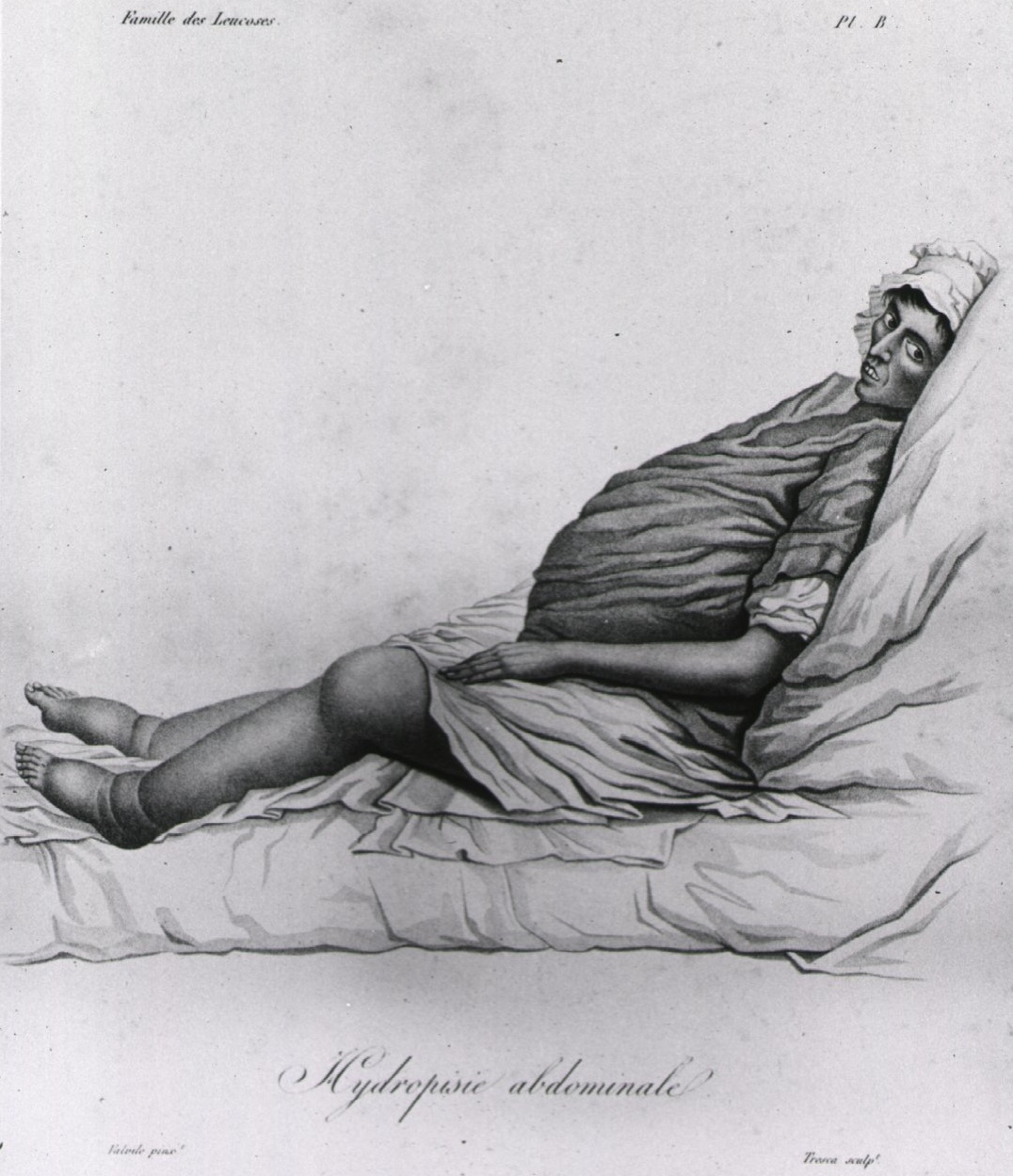

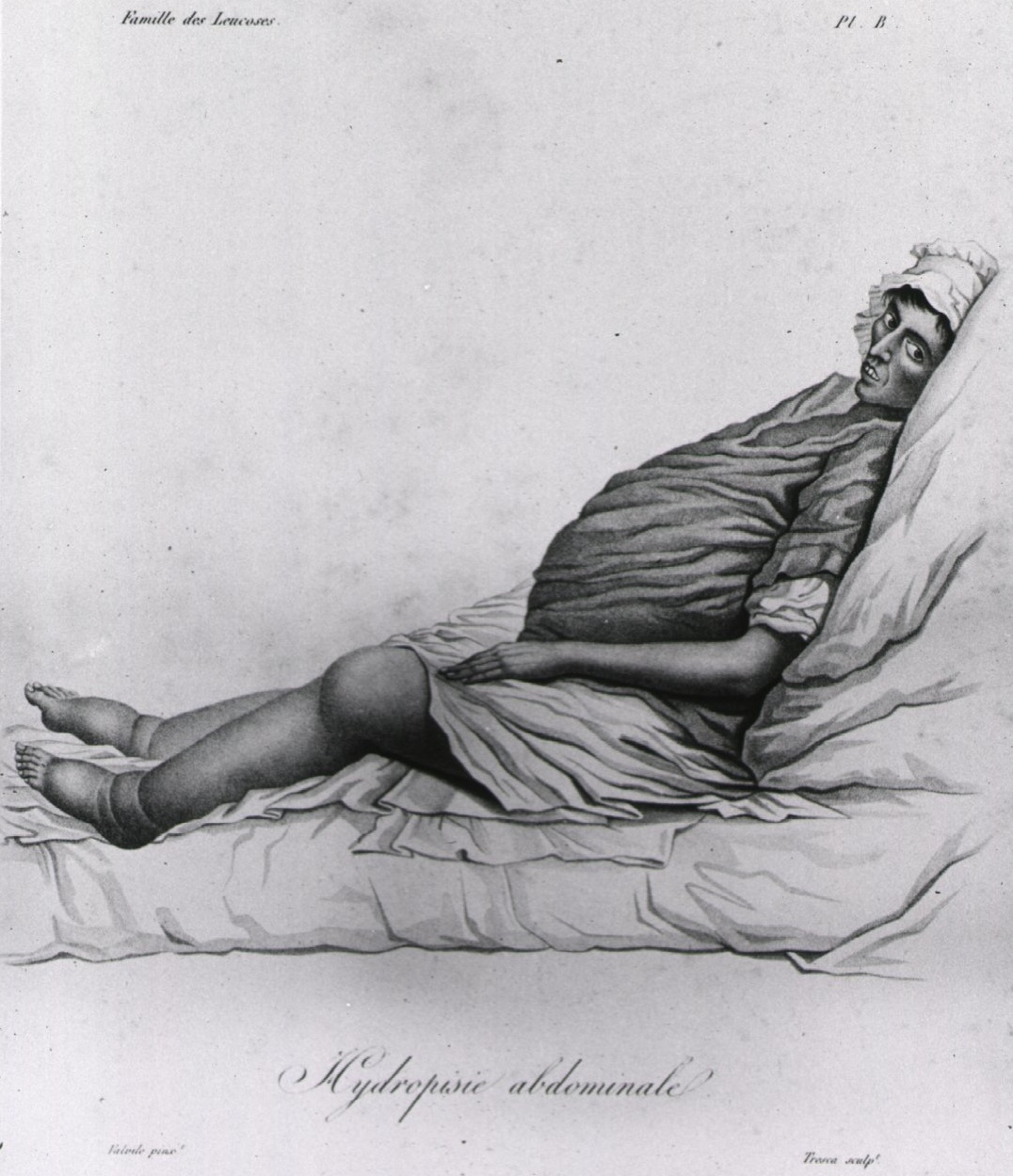

In 1827 Robert Bright published a seminal paper describing patients with dropsy (oedema), albumin in their urine and high blood pressure. This constellation of symptoms was known for over a century as Bright’s Disease.

What Bright didn’t really describe was that some patients with Bright’s Disease died very quickly whilst others recovered; some eventually got blood in their urine, some were pregnant and others were children, some were in great pain, whilst others become confused and drowsy.

In modern medicine the name “Bright’s Disease” is never used anymore because it was not a disease but a clinical syndrome, and this syndrome describes not one but a wide range of different kidney diseases. We now understand the underlying causes and disease processes of what Bright was describing and have no need for an archaic classification.

What does this have to do with Sherlock’s Bipolar or even psychiatry?

Psychiatry today is very much like what renal medicine was when Robert Bright worked at Guy’s Hospital. There is hardly any understanding of the pathology (disease process) behind the syndromes that we commonly diagnose people with. Instead diagnosis is centred on clinical syndromes. The DSM-IV and ICD-10 are merely giant checklists: if you have these symptoms, you therefore have “X”.

Psychiatric diagnosis is a prolonged exercise of putting people into predefined artificial boxes.

Bipolar Affective Disorder like many psychiatric “diseases” - is an artificial construct. This is not to say the symptoms of bipolar are not real, the symptoms can be devastating but like Bright’s Disease - what defines Bipolar is the constellation of symptoms and not an underlying pathology. The diagnostic checklist is incredibly subjective and there is no objective test for Bipolar - this puts the onus on the psychiatrist’s judgement.

In effect you have Bipolar if your psychiatrist thinks you have Bipolar. There are many people out there with the symptoms that have never been diagnosed. They are actually ill but they do not technically have Bipolar. Equally there are plenty of people with some features of Bipolar but not enough to satisfy the diagnostic criteria - they are still ill but they do not have Bipolar.

Bipolar is not like glomerulonephritis - even if you are not diagnosed, we can still demonstrate that you are undergoing the disease process. There is an objective test (kidney biopsy) and many ways of investigating the underlying cause.

In psychiatry there is no clear boundary between healthy and not-healthy, there are no absolutes.

Therefore what one psychiatrist thinks is healthy might differ completely from another. Some psychiatrists stick to the checklist, others play by their own rules. One method is not superior to another. Being labelled with a specific psychiatric condition does not change the nature of your condition - it does not make you more or less ill. It does however dictate what treatment you receive.

There are people who every psychiatrist would diagnose with Bipolar and many more who psychiatrist just can’t make up their minds about.

I have received a lot of comments from people suffering from Bipolar saying that my description of Bipolar does not match their experiences. Due the difference in opinion amongst psychiatrists of just who should be diagnosed with Bipolar the actually population of patients diagnosed with Bipolar would have incredibly diverse symptoms and clinical courses, just like the “Bright’s Disease” patients that Robert Bright studied.

Myth Busting

Bipolar affective disorder sometimes called “manic depression” is one of the most common mood disorders in the world (after depression). However, unlike straight depression, it takes longer to reach a definitive diagnosis and can be harder to treat.

What is now known as Bipolar was first described by Aretius of Cappadocia in around 150BC.

The classical understanding of Bipolar is “periods of abnormally elevated mood and/or irritability followed by periods of depression”. Of course that is too simple:

The DSM-IV currently lists two recognised types of Bipolar: bipolar type I and bipolar type II (which was called for sometime “soft” bipolar)

…and then there is cyclothymia which is not Bipolar but belongs on the spectrum of Bipolar Illness.

In the UK psychiatrists do not use DSM-IV they use ICD-10 (no matter how much NICE guidelines might talk about DMS-IV). ICD-10 has only one diagnosis called Bipolar Affective Disorder (and then lots of subtypes including Biopolar II).

The general public have a rather strange misconception that “Bipolar Illnesses” are all the same and they cause people to very emotionally unstable - swinging between joy and sorrow many times a day. This is emphatically not true (unless you have ultra-rapid cycling bipolar which is a rare and incredibly severe form that requires hospitalisation. Not to be confused with rapid-cycling which is common).

For any type of Bipolar (but not cyclothymia) your “episodes” have to be persistent, consistent and last for more than 4 days each. If left untreated patients have episodes that can last weeks. Their mood is relatively stable throughout this period without any oscillation between high and low. The change from one episode to another occurs over days not minutes and once you are in an episode you stay in that episode for significant period of time.

It is also possible to have bipolar without depression and only periods of mania and hypomania (mania that is less extreme). You can also have a double dip kind of bipolar whereby you become depressed and then even more depressed. Alternatively you can have mixed episodes. This does not mean you are happy one minute and sad the next. A mixed episode is where you exhibit symptoms of depression and mania/hypomania but your mood is relatively stable - but just not your “normal” mood.

Patients also a concept of “right” and “wrong” diagnoses. This is perfectly valid for disease that we understand the pathology of and can conclusively prove one way or the other, but in psychiatry we cannot do either of these things.

Patients who are diagnosed with Bipolar will often tick multiple other checklists just by virtue of symptom overlap but that does not mean they should be given myriads of different diagnoses - Bipolar the most appropriate i.e. the patient fits into the Bipolar box better than any others.

There is a move away from calling something the “correct” diagnosis - it is now called the “most appropriate” diagnosis. The diagnosis psychiatry only has meaning because it then prompts the doctor to give a specific form of treatment - so it is still important to give the most appropriate diagnosis.

It may take a great deal of time before the most appropriate diagnosis is reached. For example many people who go onto be diagnosed with Bipolar are first given a diagnosis of depression. Often depression was the most appropriate diagnosis at the time from the clinical history and hence not “wrong” - only with time do we realise that Bipolar is more appropriate.

Does Sherlock have Bipolar?

How likely are you to get Bipolar?

According to the Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry the lifetime prevalence is 0.3%-1.5% (0.8% Type I and 0.5% Type II)

Research usually uses DSM-IV definitions because the American academic readership is very large and very influential.

Lifetime prevalence (chance of developing the disorder over your entire life) of Bipolar Type I in European studies is 0.1%-2.4%.

Compare this prevalence for a depressive episode (as defined in ICD-10) among 16- to 74-year-olds in the UK in 2000 was 2.6%.

Bipolar type II prevalence calculations are compounded by the fact that some psychiatrists think the that diagnostic criteria at the moment for Type II is too “stringent” and have thus come up with their own much broader definition (which is not recognised).

Although the criteria for Bipolar is artificial and somewhat arbitrary (why 4 days? Why not 3 days or 5 days or a week?) - it is still the recognised standard as signed off by the leading members of the psychiatric community from around the world.

Making a much broader definition that is less stringent is a bit like a hospital manager saying: “everyone with shortness of breath and cough is now on the lung problems register” leaving the cardiologists thinking: “what about my patients with heart failure? They have those symptoms but there’s nothing wrong with their lungs.”

Even with a broader definition - the life time prevalence in European studies is calculated to be 0.2%-2.0%. Hence you are not more likely to be diagnosed with Type II.

In practice Bipolar Type I is more likely to be diagnosed earlier and more appropriately. Hence people who are diagnosed with Bipolar Type I are less likely to have their diagnosis changed. This makes Bipolar Type I patients the majority of all Bipolar patients (at least in the UK)

Sherlock as an individual would be more likely to get Bipolar if:

Sherlock lives in London - No?

Given that Sherlock lives in London, he’s much more likely to see a psychiatrist on the NHS rather than a private psychiatrist who has trained abroad and is penchant for DSM-IV.

So what does ICD-10 say about Bipolar Affective Disorder.

“A disorder characterized by two or more episodes in which the patient's mood and activity levels are significantly disturbed, this disturbance consisting on some occasions of an elevation of mood and increased energy and activity (hypomania or mania) and on others of a lowering of mood and decreased energy and activity (depression). Repeated episodes of hypomania or mania only are classified as bipolar.”

What the ICD-10 doesn’t do is spell out what hypomania/mania in a convenient checklist like DSM-IV does. If you are a psychiatrist - it is perfectly acceptable to use the DSM-IV checklist for mania/hypomania as long as it doesn’t contradict ICD-10 - it’s your personal choice.

What is mania?

ICD-10 classifies a manic episode without psychotic symptoms as:

“Mood is elevated out of keeping with the patient's circumstances and may vary from carefree joviality to almost uncontrollable excitement. Elation is accompanied by increased energy, resulting in overactivity, pressure of speech, and a decreased need for sleep. Attention cannot be sustained, and there is often marked distractibility. Self-esteem is often inflated with grandiose ideas and overconfidence. Loss of normal social inhibitions may result in behaviour that is reckless, foolhardy, or inappropriate to the circumstances, and out of character.”

What About Hypomania?

“A disorder characterized by a persistent mild elevation of mood, increased energy and activity, and usually marked feelings of well-being and both physical and mental efficiency. Increased sociability, talkativeness, over-familiarity, increased sexual energy, and a decreased need for sleep are often present but not to the extent that they lead to severe disruption of work or result in social rejection.

Irritability, conceit, and boorish behaviour may take the place of the more usual euphoric sociability. The disturbances of mood and behaviour are not accompanied by hallucinations or delusions.”

Does Sherlock have Bipolar? - Come on Answer the Question!

Before I give my semi-professional opinion: the important point to remember is that during a Bipolar episode “the patient’s mood and activity must be significantly disturbed”.

In terms of mania:

If the patient is usually reckless, restless, aggressive and irritable, he must demonstrate that these characteristics become significantly more severe without any logical reason during a prolong period of time. Seen as Sherlock’s elevated moods almost always coincide with either pursuing or solving a case, we can conclude that Sherlock has a very logical reason to be happy and his mood is not “out of keeping with his circumstances”

We have no idea regarding Sherlock’s sleeping habits. He does not appear to suffer from insomnia - a lack of sleep is not alluded to in the series, so it is unfortunately that we cannot comment on whether he has decreased need to sleep.

Otherwise - Sherlock does not become persistently and markedly distracted during a specific period of time. His concentration does not appear to be affected by his elevated moods.

The general picture is not one that fits well with a manic episode.

However he does display some signs of hypomania i.e. “persistent mild elevation of mood, increased energy and activity”. The elevation of mood has to be minimum 4 days (borrowed from DSM-IV criteria). Given we do not have a good idea of the time scale of Sherlock’s cases in the series, it is hard to calculate how long Sherlock’s mood elevations last for. On the other hand he almost always has a great deal of energy on or off a case. It is improbable that Sherlock has been in a hypomanic state for 18 months but it’s not impossible)

There is no marked increase in sociability or over-familiarness and we do not know enough about Sherlock’s sex life to comment on his libido during periods of elevated mood. Otherwise it is difficult to see a distinct fluctuation in his talkatively. Sherlock appears to talk a lot when there is a lot he wants to talk about.

He does fit the description: “Irritability, conceit, and boorish behaviour may take the place of the more usual euphoric sociability” but once again he does not display these behaviours for a limited and specific time period and then reverts back to a significantly different set of behaviours.

So basically although he fulfils some of the hypomania criteria - the long duration and lack of fluctuation in his behaviour appears to suggest that he is not actually experiencing episodes of anything. What we are seeing his is “normal”.

However - Sherlock demonstrates symptoms that could allow him to be included into a group called (rather disingenuously) “soft” Bipolar II or broadly-defined Bipolar II.

These are patients who have some symptoms of Bipolar but do not fulfil the entire criteria. A debate rages over whether the diagnostic criteria should be changed so that these people are also included under the title of Bipolar.

The question is, as we see him now, does Sherlock benefit from a psychiatric diagnosis?

The Flip Side of the Coin

Going back to the Bipolar Affective Disorder “and on others of a lowering of mood and decreased energy and activity (depression)”, technically you need a period of depression in order to qualify for a diagnosis but as I said psychiatrists come in pedantic and not-so-pedantic varieties so even if you don’t have low moods you can still get a diagnosis of bipolar.

I am convinced that Sherlock has never displayed signs of a depression episode. Clinical depression (depression episode ICD-10) is not just characterised by abnormally low mood, it also requires ahendonia (not enjoying the things one usually enjoys) and low energy. Sherlock has never displayed the latter two symptoms even during periods where he has low mood e.g. TRF. In TRF Sherlock has every reason to have low mood, he’s about to fake his own death and devastate his only friend. I would be worried if he was happy - because that would actually be a sign of mania. Sherlock is still able to functional perfectly well and enjoy solving cases to the same extent as usual during times when he is “down”, in fact cases are the perfect antidote to his low mood, which shows that he is not actually depressed - he is merely sulking. As anyone who has been depressed will know, it takes time and a great deal of effort to lift yourself out of depression. It will not happen instantaneously due to one set of stimuli.

As a commentor pointed out there are other types of low mood disorders: including atypical depression which has mood reactivity. Mood reactivity means that you are able to experience enjoyment in response to perceived positive stimuli - but you revert back to the “low”. However the majority of Bipolar episodes with low mood are depression episodes.

Additionally if Sherlock truly had bipolar, his episodes would not coincide perfectly with his work schedule. The majority of patients have no control over when or how their mood cycles.

I also think it is unlikely that Sherlock has a purely manic or a purely depressive type of bipolar disorder (some psychiatrists refuse to diagnose patients with Bipolar).

The usual pattern contains periods of time where Sherlock should essentially be in remission - i.e. behaving “normally”. However we do not see periods (even short ones) during which Sherlock behaves significantly more calmly or more “normally”. It is more likely that what we see of Sherlock is not one extremely long hypomanic episode but rather what we see is his norm. He is naturally brimming with energy, self-esteem and recklessness.

Of course Sherlock may have had bipolar in the past, and is now on medication which controls his symptoms but I discuss in the next article why Sherlock might object to treatment if he had bipolar.

I would not diagnose the BBC version of Sherlock with bipolar affective disorder if he presented at any time during the series. I really don't think labelling Sherlock with any type of psychiatric condition is helpful or conducive to improving his quality of life.

If he has symptoms - he does not appear to find them a) dysfunctional or b) debilitating. Sherlock appears to be well-functioning and generally living a full, meaningful life. What can we add by labelling him "bipolar" or "asperger's" or "psychopathic"?

As for ACD Holmes - there is somewhat more convincing evidence that he may be displaying signs of hypomania and depression. I read a great scientific paper a long time ago on why ACD Holmes could be diagnosed with Bipolar but I cannot find it on pubmed anymore. If anyone else knows the link please tell me so I can added to this section.

In the last article I have many comments saying that I did not give enough information about Bipolar. So now I have completely rewritten the article.

- Syndromes and disease - an explanation of how psychiatric diagnoses work

- Some myth busting regarding Bipolar and the differences between countries in terms of diagnosis

- An evaluation of Sherlock's behaviour to see if he would be diagnosed with Bipolar in the UK

Syndromes and Disease - A Step Back in Time

In 1827 Robert Bright published a seminal paper describing patients with dropsy (oedema), albumin in their urine and high blood pressure. This constellation of symptoms was known for over a century as Bright’s Disease.

What Bright didn’t really describe was that some patients with Bright’s Disease died very quickly whilst others recovered; some eventually got blood in their urine, some were pregnant and others were children, some were in great pain, whilst others become confused and drowsy.

In modern medicine the name “Bright’s Disease” is never used anymore because it was not a disease but a clinical syndrome, and this syndrome describes not one but a wide range of different kidney diseases. We now understand the underlying causes and disease processes of what Bright was describing and have no need for an archaic classification.

What does this have to do with Sherlock’s Bipolar or even psychiatry?

Psychiatry today is very much like what renal medicine was when Robert Bright worked at Guy’s Hospital. There is hardly any understanding of the pathology (disease process) behind the syndromes that we commonly diagnose people with. Instead diagnosis is centred on clinical syndromes. The DSM-IV and ICD-10 are merely giant checklists: if you have these symptoms, you therefore have “X”.

Psychiatric diagnosis is a prolonged exercise of putting people into predefined artificial boxes.

Bipolar Affective Disorder like many psychiatric “diseases” - is an artificial construct. This is not to say the symptoms of bipolar are not real, the symptoms can be devastating but like Bright’s Disease - what defines Bipolar is the constellation of symptoms and not an underlying pathology. The diagnostic checklist is incredibly subjective and there is no objective test for Bipolar - this puts the onus on the psychiatrist’s judgement.

In effect you have Bipolar if your psychiatrist thinks you have Bipolar. There are many people out there with the symptoms that have never been diagnosed. They are actually ill but they do not technically have Bipolar. Equally there are plenty of people with some features of Bipolar but not enough to satisfy the diagnostic criteria - they are still ill but they do not have Bipolar.

Bipolar is not like glomerulonephritis - even if you are not diagnosed, we can still demonstrate that you are undergoing the disease process. There is an objective test (kidney biopsy) and many ways of investigating the underlying cause.

In psychiatry there is no clear boundary between healthy and not-healthy, there are no absolutes.

Therefore what one psychiatrist thinks is healthy might differ completely from another. Some psychiatrists stick to the checklist, others play by their own rules. One method is not superior to another. Being labelled with a specific psychiatric condition does not change the nature of your condition - it does not make you more or less ill. It does however dictate what treatment you receive.

There are people who every psychiatrist would diagnose with Bipolar and many more who psychiatrist just can’t make up their minds about.

I have received a lot of comments from people suffering from Bipolar saying that my description of Bipolar does not match their experiences. Due the difference in opinion amongst psychiatrists of just who should be diagnosed with Bipolar the actually population of patients diagnosed with Bipolar would have incredibly diverse symptoms and clinical courses, just like the “Bright’s Disease” patients that Robert Bright studied.

Myth Busting

Bipolar affective disorder sometimes called “manic depression” is one of the most common mood disorders in the world (after depression). However, unlike straight depression, it takes longer to reach a definitive diagnosis and can be harder to treat.

What is now known as Bipolar was first described by Aretius of Cappadocia in around 150BC.

The classical understanding of Bipolar is “periods of abnormally elevated mood and/or irritability followed by periods of depression”. Of course that is too simple:

The DSM-IV currently lists two recognised types of Bipolar: bipolar type I and bipolar type II (which was called for sometime “soft” bipolar)

…and then there is cyclothymia which is not Bipolar but belongs on the spectrum of Bipolar Illness.

In the UK psychiatrists do not use DSM-IV they use ICD-10 (no matter how much NICE guidelines might talk about DMS-IV). ICD-10 has only one diagnosis called Bipolar Affective Disorder (and then lots of subtypes including Biopolar II).

The general public have a rather strange misconception that “Bipolar Illnesses” are all the same and they cause people to very emotionally unstable - swinging between joy and sorrow many times a day. This is emphatically not true (unless you have ultra-rapid cycling bipolar which is a rare and incredibly severe form that requires hospitalisation. Not to be confused with rapid-cycling which is common).

For any type of Bipolar (but not cyclothymia) your “episodes” have to be persistent, consistent and last for more than 4 days each. If left untreated patients have episodes that can last weeks. Their mood is relatively stable throughout this period without any oscillation between high and low. The change from one episode to another occurs over days not minutes and once you are in an episode you stay in that episode for significant period of time.

It is also possible to have bipolar without depression and only periods of mania and hypomania (mania that is less extreme). You can also have a double dip kind of bipolar whereby you become depressed and then even more depressed. Alternatively you can have mixed episodes. This does not mean you are happy one minute and sad the next. A mixed episode is where you exhibit symptoms of depression and mania/hypomania but your mood is relatively stable - but just not your “normal” mood.

Patients also a concept of “right” and “wrong” diagnoses. This is perfectly valid for disease that we understand the pathology of and can conclusively prove one way or the other, but in psychiatry we cannot do either of these things.

Patients who are diagnosed with Bipolar will often tick multiple other checklists just by virtue of symptom overlap but that does not mean they should be given myriads of different diagnoses - Bipolar the most appropriate i.e. the patient fits into the Bipolar box better than any others.

There is a move away from calling something the “correct” diagnosis - it is now called the “most appropriate” diagnosis. The diagnosis psychiatry only has meaning because it then prompts the doctor to give a specific form of treatment - so it is still important to give the most appropriate diagnosis.

It may take a great deal of time before the most appropriate diagnosis is reached. For example many people who go onto be diagnosed with Bipolar are first given a diagnosis of depression. Often depression was the most appropriate diagnosis at the time from the clinical history and hence not “wrong” - only with time do we realise that Bipolar is more appropriate.

Does Sherlock have Bipolar?

How likely are you to get Bipolar?

According to the Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry the lifetime prevalence is 0.3%-1.5% (0.8% Type I and 0.5% Type II)

Research usually uses DSM-IV definitions because the American academic readership is very large and very influential.

Lifetime prevalence (chance of developing the disorder over your entire life) of Bipolar Type I in European studies is 0.1%-2.4%.

Compare this prevalence for a depressive episode (as defined in ICD-10) among 16- to 74-year-olds in the UK in 2000 was 2.6%.

Bipolar type II prevalence calculations are compounded by the fact that some psychiatrists think the that diagnostic criteria at the moment for Type II is too “stringent” and have thus come up with their own much broader definition (which is not recognised).

Although the criteria for Bipolar is artificial and somewhat arbitrary (why 4 days? Why not 3 days or 5 days or a week?) - it is still the recognised standard as signed off by the leading members of the psychiatric community from around the world.

Making a much broader definition that is less stringent is a bit like a hospital manager saying: “everyone with shortness of breath and cough is now on the lung problems register” leaving the cardiologists thinking: “what about my patients with heart failure? They have those symptoms but there’s nothing wrong with their lungs.”

Even with a broader definition - the life time prevalence in European studies is calculated to be 0.2%-2.0%. Hence you are not more likely to be diagnosed with Type II.

In practice Bipolar Type I is more likely to be diagnosed earlier and more appropriately. Hence people who are diagnosed with Bipolar Type I are less likely to have their diagnosis changed. This makes Bipolar Type I patients the majority of all Bipolar patients (at least in the UK)

Sherlock as an individual would be more likely to get Bipolar if:

- Family history - if he has a first degree relative with Bipolar he is 7 times more likely to develop it

- Studies in identical twins show 30% - 50% concordance - so genetics plays a significant part

Sherlock lives in London - No?

Given that Sherlock lives in London, he’s much more likely to see a psychiatrist on the NHS rather than a private psychiatrist who has trained abroad and is penchant for DSM-IV.

So what does ICD-10 say about Bipolar Affective Disorder.

“A disorder characterized by two or more episodes in which the patient's mood and activity levels are significantly disturbed, this disturbance consisting on some occasions of an elevation of mood and increased energy and activity (hypomania or mania) and on others of a lowering of mood and decreased energy and activity (depression). Repeated episodes of hypomania or mania only are classified as bipolar.”

What the ICD-10 doesn’t do is spell out what hypomania/mania in a convenient checklist like DSM-IV does. If you are a psychiatrist - it is perfectly acceptable to use the DSM-IV checklist for mania/hypomania as long as it doesn’t contradict ICD-10 - it’s your personal choice.

What is mania?

ICD-10 classifies a manic episode without psychotic symptoms as:

“Mood is elevated out of keeping with the patient's circumstances and may vary from carefree joviality to almost uncontrollable excitement. Elation is accompanied by increased energy, resulting in overactivity, pressure of speech, and a decreased need for sleep. Attention cannot be sustained, and there is often marked distractibility. Self-esteem is often inflated with grandiose ideas and overconfidence. Loss of normal social inhibitions may result in behaviour that is reckless, foolhardy, or inappropriate to the circumstances, and out of character.”

What About Hypomania?

“A disorder characterized by a persistent mild elevation of mood, increased energy and activity, and usually marked feelings of well-being and both physical and mental efficiency. Increased sociability, talkativeness, over-familiarity, increased sexual energy, and a decreased need for sleep are often present but not to the extent that they lead to severe disruption of work or result in social rejection.

Irritability, conceit, and boorish behaviour may take the place of the more usual euphoric sociability. The disturbances of mood and behaviour are not accompanied by hallucinations or delusions.”

Does Sherlock have Bipolar? - Come on Answer the Question!

Before I give my semi-professional opinion: the important point to remember is that during a Bipolar episode “the patient’s mood and activity must be significantly disturbed”.

In terms of mania:

If the patient is usually reckless, restless, aggressive and irritable, he must demonstrate that these characteristics become significantly more severe without any logical reason during a prolong period of time. Seen as Sherlock’s elevated moods almost always coincide with either pursuing or solving a case, we can conclude that Sherlock has a very logical reason to be happy and his mood is not “out of keeping with his circumstances”

We have no idea regarding Sherlock’s sleeping habits. He does not appear to suffer from insomnia - a lack of sleep is not alluded to in the series, so it is unfortunately that we cannot comment on whether he has decreased need to sleep.

Otherwise - Sherlock does not become persistently and markedly distracted during a specific period of time. His concentration does not appear to be affected by his elevated moods.

The general picture is not one that fits well with a manic episode.

However he does display some signs of hypomania i.e. “persistent mild elevation of mood, increased energy and activity”. The elevation of mood has to be minimum 4 days (borrowed from DSM-IV criteria). Given we do not have a good idea of the time scale of Sherlock’s cases in the series, it is hard to calculate how long Sherlock’s mood elevations last for. On the other hand he almost always has a great deal of energy on or off a case. It is improbable that Sherlock has been in a hypomanic state for 18 months but it’s not impossible)

There is no marked increase in sociability or over-familiarness and we do not know enough about Sherlock’s sex life to comment on his libido during periods of elevated mood. Otherwise it is difficult to see a distinct fluctuation in his talkatively. Sherlock appears to talk a lot when there is a lot he wants to talk about.

He does fit the description: “Irritability, conceit, and boorish behaviour may take the place of the more usual euphoric sociability” but once again he does not display these behaviours for a limited and specific time period and then reverts back to a significantly different set of behaviours.

So basically although he fulfils some of the hypomania criteria - the long duration and lack of fluctuation in his behaviour appears to suggest that he is not actually experiencing episodes of anything. What we are seeing his is “normal”.

However - Sherlock demonstrates symptoms that could allow him to be included into a group called (rather disingenuously) “soft” Bipolar II or broadly-defined Bipolar II.

These are patients who have some symptoms of Bipolar but do not fulfil the entire criteria. A debate rages over whether the diagnostic criteria should be changed so that these people are also included under the title of Bipolar.

The question is, as we see him now, does Sherlock benefit from a psychiatric diagnosis?

The Flip Side of the Coin

Going back to the Bipolar Affective Disorder “and on others of a lowering of mood and decreased energy and activity (depression)”, technically you need a period of depression in order to qualify for a diagnosis but as I said psychiatrists come in pedantic and not-so-pedantic varieties so even if you don’t have low moods you can still get a diagnosis of bipolar.

I am convinced that Sherlock has never displayed signs of a depression episode. Clinical depression (depression episode ICD-10) is not just characterised by abnormally low mood, it also requires ahendonia (not enjoying the things one usually enjoys) and low energy. Sherlock has never displayed the latter two symptoms even during periods where he has low mood e.g. TRF. In TRF Sherlock has every reason to have low mood, he’s about to fake his own death and devastate his only friend. I would be worried if he was happy - because that would actually be a sign of mania. Sherlock is still able to functional perfectly well and enjoy solving cases to the same extent as usual during times when he is “down”, in fact cases are the perfect antidote to his low mood, which shows that he is not actually depressed - he is merely sulking. As anyone who has been depressed will know, it takes time and a great deal of effort to lift yourself out of depression. It will not happen instantaneously due to one set of stimuli.

As a commentor pointed out there are other types of low mood disorders: including atypical depression which has mood reactivity. Mood reactivity means that you are able to experience enjoyment in response to perceived positive stimuli - but you revert back to the “low”. However the majority of Bipolar episodes with low mood are depression episodes.

Additionally if Sherlock truly had bipolar, his episodes would not coincide perfectly with his work schedule. The majority of patients have no control over when or how their mood cycles.

I also think it is unlikely that Sherlock has a purely manic or a purely depressive type of bipolar disorder (some psychiatrists refuse to diagnose patients with Bipolar).

The usual pattern contains periods of time where Sherlock should essentially be in remission - i.e. behaving “normally”. However we do not see periods (even short ones) during which Sherlock behaves significantly more calmly or more “normally”. It is more likely that what we see of Sherlock is not one extremely long hypomanic episode but rather what we see is his norm. He is naturally brimming with energy, self-esteem and recklessness.

Of course Sherlock may have had bipolar in the past, and is now on medication which controls his symptoms but I discuss in the next article why Sherlock might object to treatment if he had bipolar.

I would not diagnose the BBC version of Sherlock with bipolar affective disorder if he presented at any time during the series. I really don't think labelling Sherlock with any type of psychiatric condition is helpful or conducive to improving his quality of life.

If he has symptoms - he does not appear to find them a) dysfunctional or b) debilitating. Sherlock appears to be well-functioning and generally living a full, meaningful life. What can we add by labelling him "bipolar" or "asperger's" or "psychopathic"?

As for ACD Holmes - there is somewhat more convincing evidence that he may be displaying signs of hypomania and depression. I read a great scientific paper a long time ago on why ACD Holmes could be diagnosed with Bipolar but I cannot find it on pubmed anymore. If anyone else knows the link please tell me so I can added to this section.